The Colon

Michael Davis

M. Davis: Department of Radiology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131-5336.

THE COLON

Indications

The major reasons for studying the large bowel relate to colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. Both bright red rectal bleeding and chemical evidence of hemoglobin products in the stool are strong indications. Subacute or chronic diarrhea suggests the possibility of inflammatory bowel disease. Other symptoms and signs that may indicate the presence of colonic disease include a change in caliber of the stool, constipation, and weight loss, but most often no organic bowel disease is found in these patients. Severe anemia is sometimes seen with right-colon neoplasms. Abdominal distention raises the possibility of colonic obstruction. The presence of a left-lower-quadrant mass with tenderness suggests diverticulitis or tubo-ovarian abscess, and the same findings in the right-lower quadrant can occur with an appendiceal or tubo-ovarian abscess. The colon is often studied in patients with genitourinary malignancies to exclude invasion of the gut.

Anatomy

The mobile portions of the colon are the sigmoid and transverse portions; they have a longer mesentery and can shift more in position. The cecum also may be mobile if it has a long mesentery—a situation that may lead to cecal volvulus. The rest of the colon has a short mesentery and is fixed in position. The rectum is an extraperitoneal structure and has a fixed position. There is considerable variation in the position of the appendix. Although it usually is in the right-lower quadrant, it can move with the cecum, may be retrocecal, and occasionally is long with the tip extending into the subhepatic region.

Physiology

Water absorption occurs in the right colon, but the main function of the colon is the storage and transport of feces. The contraction waves in the colon are not ordinarily a subject of radiologic study. The anal sphincter is under voluntary control.

Methods of Examination

Plain films of the abdomen have great value in detecting colonic obstruction, colonic ileus, and the toxic megacolon syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease. The dilated colon can readily be appreciated in all these conditions.

Single- and double-contrast examinations with barium sulfate are the usual methods used to study the colon. In these combined fluoroscopic-radiographic procedures, the contrast agents are introduced through the rectum under fluoroscopic observation. A controversy exists concerning single- versus double-contrast studies, but the prevailing opinion is that smaller lesions of the colon, such as aphthous ulcers and small polyps, can be detected better with the double-contrast method.

Of vital importance in barium enema studies is a clean colon. All combinations of cathartics and enemas have been tried. The regimens that work best include a purgative or laxative with copious amounts of oral liquids (the latter acting as a flush).14 Enemas employing water-soluble contrast agents are indicated if colonic perforation is suspected, and they occasionally are used to soften a fecal impaction. Ultrasonography can be of great help in identifying abscesses and bowel-wall thickening that may accompany inflammatory disease. Occasionally, nonpalpable abdominal masses are also found by ultrasonography. Because of the presence of colonic gas, ultrasonography is not often a useful method for detecting the ordinary intraluminal lesions. Computed tomography (CT) is valuable for determining the presence and extent of extracolonic disease. Abscess, fistula, diverticulitis, and lymphadenopathy can be detected by CT.

Alternative Nonradiologic Methods

Colonoscopy is a competitive alternative to barium studies of the colon. There is a distinct advantage in being able to view the mucosa directly and to biopsy suspicious lesions at the time of this examination. The current disadvantages of colonoscopy are the inability to see the entire colon in some patients and the cost, which is considerably more than a radiologic study. Sigmoidoscopy continues to be a supportive and complementary adjunct to radiologic studies. The detection of anal canal lesions in particular is much better accomplished by direct observation.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Tubulation Defects

Although any part of the colon may be atretic, the most common clinical problem is anorectal atresia. By allowing intestinal gas to reach the sigmoid colon, the proximal site of the obstruction can be determined. Fistulae to the vagina and bladder can occur in the imperforate anus syndrome. Knowing the length of the atresia helps in planning reparative surgery.

Colonic Duplication

Duplication of the colon is rare. The duplication may or may not communicate with the functioning colon. Barium studies may show a double lumen (Fig. 19-1). Ultrasonography can determine the cystic nature of a noncommunicating duplication anomaly.

Failures of Rotation

Nonrotation places the entire colon on the left side of the abdomen. Incomplete rotation and fixation of the colon may leave the cecum unusually mobile and prone to volvulus (Fig. 19-2).

Aganglionic Megacolon

Aganglionosis of the colon causes the colon to be functionally partially obstructed at the site where the aganglionosis begins. This site can be anywhere from the cecum to the rectum. Progressive dilatation of the colon occurs; barium enema and biopsy lead to the correct diagnosis. The colon may appear normal as it is filled with barium, but there is a failure to evacuate the barium through the aganglionic area (Fig. 19-3). The most difficult type to detect is aganglionosis involving only the anal canal area. Patients with this condition commonly have the meconium plug syndrome at birth. The rectal meconium is obstructive until it is passed spontaneously or by the aid of an enema. Later the infant’s constipation becomes apparent, and the colonic dilatation down to the anus is detected. Biopsy then confirms the aganglionosis. Functional megacolon may simulate aganglionosis of the anal canal on barium enema, except that in the functional type dilatation is usually greatest in the rectum.

INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

Extrinsic Agents

It is rare for people to introduce damaging agents into the rectum, but colonic damage has been reported in children who were repeatedly given detergent enemas. Adults may have the cathartic colon syndrome,47 in which the haustrations of the colon are obliterated owing to damage to the autonomic nervous system of colon, which leaves a very smooth internal contour (Fig. 19-4). It usually involves the right colon more than the left and is caused by long-standing laxative abuse. Few cases of cathartic colon have been observed in recent decades, probably because the laxatives commonly at fault are no longer in use.29, 30 Radiation damage to the rectum and sigmoid after treatment of genitourinary malignancies is now rare. The strictures that occur are caused by damage to the small blood vessels. The radiographic findings are stricture or lack of normal distensibility.

Specific Organisms

Acute and self-limited infectious colitis is rarely studied radiologically. The same holds true for most types of subacute colitis. Amebiasis and tuberculosis are more chronic diarrheal diseases. Tuberculosis classically involves the ileocecal area with ulceration and stricture formation (Fig. 19-5). Amebiasis tends to be a cecal inflammatory process, with the cecum sometimes completely obliterated after healing occurs (Fig. 19-6).27 Tuberculosis and amebiasis may have skip lesions and closely mimic Crohn’s disease. An amebic inflammatory mass, referred to as an ameboma, can occur anywhere in the colon and may mimic a neoplasm. Both tuberculosis and amebiasis may manifest as a diffuse ulcerating colitis. Schistosomiasis can produce a chronic ulcerating colitis and can go on to pseudopolyp formation, manifested by multiple small filling defects which project

into the colonic lumen. Yersinia infection occurs in the distal ileum and right colon and can mimic Crohn’s disease. Clostridium septicum and Clostridium perfringens have been observed to cause severe ulcerative colitis with gas formation in the colonic wall; patients with this condition often have malignant neoplasms.38,39 Herpes simplex can cause deep aphthous and collar-button ulcers of the anus and rectum.41 Campylobacter frequently causes a subacute colitis which

can develop into toxic megacolon.2 The radiographic findings are those of ulceration and edema not unlike those seen in ulcerative colitis. The lack of immune competence may lead to colitis caused by unusual organisms such as cytomegalovirus or Candida.13, 42 Venereal-related colitis, usually proctitis, can be caused by gonococcus and many other organisms such as Mycoplasma and Entamoeba in addition to herpes simplex.16, 43 Lymphogranuloma venereum infection can result in edema and ulceration followed by extensive strictures in the anorectal area. Pseudomembranous colitis is the result of a toxin liberated by Clostridium difficile. Because this organism frequently overgrows the colon after antibiotic therapy, this condition was previously called antibiotic colitis. The radiographic pattern is slightly different from the usual ulcerative process, because mucosal edema predominates (Fig. 19-7). The colonic surface may appear irregular and shaggy as a result of the pseudomembrane and superficial ulceration. The disease usually involves the entire colon, but cases of rectal sparing have been reported.37 When the disease is severe, barium enema is contraindicated.

into the colonic lumen. Yersinia infection occurs in the distal ileum and right colon and can mimic Crohn’s disease. Clostridium septicum and Clostridium perfringens have been observed to cause severe ulcerative colitis with gas formation in the colonic wall; patients with this condition often have malignant neoplasms.38,39 Herpes simplex can cause deep aphthous and collar-button ulcers of the anus and rectum.41 Campylobacter frequently causes a subacute colitis which

can develop into toxic megacolon.2 The radiographic findings are those of ulceration and edema not unlike those seen in ulcerative colitis. The lack of immune competence may lead to colitis caused by unusual organisms such as cytomegalovirus or Candida.13, 42 Venereal-related colitis, usually proctitis, can be caused by gonococcus and many other organisms such as Mycoplasma and Entamoeba in addition to herpes simplex.16, 43 Lymphogranuloma venereum infection can result in edema and ulceration followed by extensive strictures in the anorectal area. Pseudomembranous colitis is the result of a toxin liberated by Clostridium difficile. Because this organism frequently overgrows the colon after antibiotic therapy, this condition was previously called antibiotic colitis. The radiographic pattern is slightly different from the usual ulcerative process, because mucosal edema predominates (Fig. 19-7). The colonic surface may appear irregular and shaggy as a result of the pseudomembrane and superficial ulceration. The disease usually involves the entire colon, but cases of rectal sparing have been reported.37 When the disease is severe, barium enema is contraindicated.

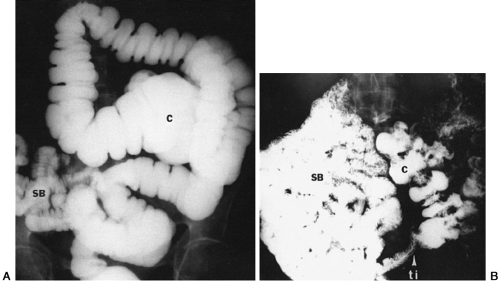

FIG. 19-5. Tuberculosis. Classically, there is ileocecal involvement with both ulceration and luminal narrowing in intestinal tuberculosis. |

FIG. 19-6.Amebiasis. The cecum is cone shaped in this instance and may become very small after healing. |

Appendicitis

Obstruction of the appendix leads to a sequence of inflammation, perforation, and abscess formation. Although appendicitis is a very common condition, the use of imaging techniques for diagnosis is rare. Early in the disease process, plain films may be normal or may show slight gaseous distention of the ileum. With perforation and abscess the terminal ileum may be involved enough to resemble a partial or complete small-bowel obstruction.

Plain films can also detect free air of perforation, right-lower-quadrant mass, obliteration of psoas muscle margin,

fading or haziness of right transversalis fascia (flank stripe), mottled or soap-bubble gas collections, and scoliosis with the concavity toward the side of inflammation. An appendicolith calcifies about 10% of the time. It usually appears as peripheral concentric calcification, but a laminated and homogeneous calcification pattern can occur. The appendicolith may be seen in a radius of 6 to 8 cm from the middle of the right iliac bone. It should be seen on both the supine and upright plain films of the abdomen that must include all of the pelvis. Appendicoliths can move with change in body position but may be fixed if significant inflammation has developed. A stone in the appendix suggests the diagnosis. Barium studies in simple appendicitis have been somewhat controversial. It is agreed that lack of appendiceal lumen filling can occur normally and does not justify a positive diagnosis. The filling of the entire appendix does exclude appendicitis. Some believe that there is spasm of the terminal ileum and cecum in appendicitis and that it can be detected at fluoroscopy. Because this is such a subjective observation, it is difficult to assess.7 With abscess formation, ultrasonography, CT, and barium studies are all helpful in identifying the morphologic changes (Fig. 19-8).

fading or haziness of right transversalis fascia (flank stripe), mottled or soap-bubble gas collections, and scoliosis with the concavity toward the side of inflammation. An appendicolith calcifies about 10% of the time. It usually appears as peripheral concentric calcification, but a laminated and homogeneous calcification pattern can occur. The appendicolith may be seen in a radius of 6 to 8 cm from the middle of the right iliac bone. It should be seen on both the supine and upright plain films of the abdomen that must include all of the pelvis. Appendicoliths can move with change in body position but may be fixed if significant inflammation has developed. A stone in the appendix suggests the diagnosis. Barium studies in simple appendicitis have been somewhat controversial. It is agreed that lack of appendiceal lumen filling can occur normally and does not justify a positive diagnosis. The filling of the entire appendix does exclude appendicitis. Some believe that there is spasm of the terminal ileum and cecum in appendicitis and that it can be detected at fluoroscopy. Because this is such a subjective observation, it is difficult to assess.7 With abscess formation, ultrasonography, CT, and barium studies are all helpful in identifying the morphologic changes (Fig. 19-8).

Idiopathic Colitides

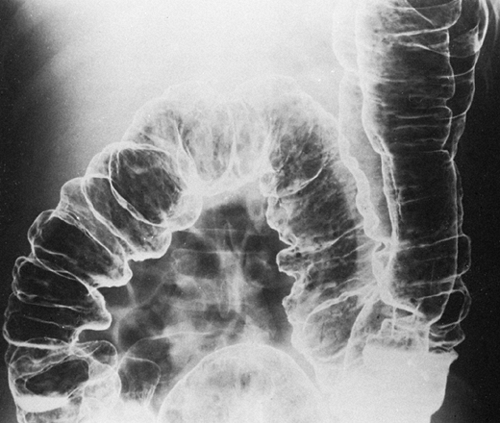

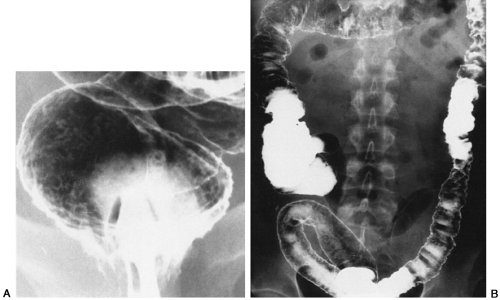

Ulcerative colitis (Fig. 19-9) and Crohn’s (granulomatous) colitis (Fig. 19-10) can most often be distinguished by radiographic changes (Table 19-1). In a small percentage of cases a clear distinction is not possible even with microscopic study of the colon. Toxic megacolon, pseudopolyposis, and an increased risk of colon carcinoma occur in both conditions but are more common in idiopathic ulcerative colitis.31 Two clear risk factors for cancer development are duration and extent of disease. Cancers arising in this setting of chronic colitis are from dysplastic epithelium and not from adenomatous polyps as is the usual case.48 Barium

studies aid the primary diagnosis, and ultrasonography and CT are helpful if complications develop. CT can directly image the bowel wall, lymph nodes, and adjacent mesentery for complications such as abscess, fistula, sinus tract, perirectal changes, and hepatobiliary, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal complications.17 Identification of early carcinoma in ulcerative colitis requires colonoscopy and biopsy.

studies aid the primary diagnosis, and ultrasonography and CT are helpful if complications develop. CT can directly image the bowel wall, lymph nodes, and adjacent mesentery for complications such as abscess, fistula, sinus tract, perirectal changes, and hepatobiliary, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal complications.17 Identification of early carcinoma in ulcerative colitis requires colonoscopy and biopsy.

FIG. 19-9. A: Acute early ulcerative colitis. Note numerous ulcerations throughout the mucosa. B Ulcerative colitis involves entire colon. |

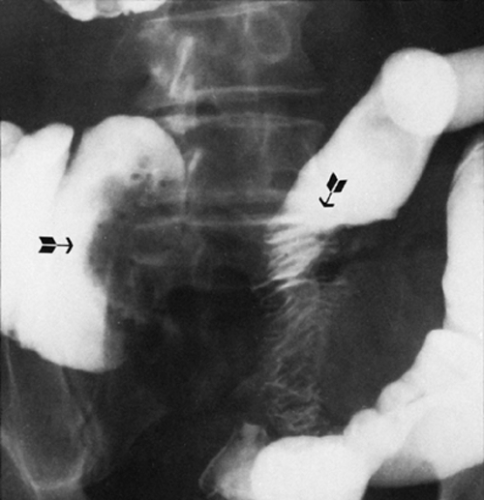

FIG. 19-10. A: Early Crohn’s disease manifested by numerous small aphthous ulcerations (arrows). B: Advanced Crohn’s disease. Deep, penetrating ulcers of the lateral wall (“rose-thorn” ulcerations) (arrows). C: Crohn’s disease with two advanced areas of involvement (arrows) and a long segment of relatively normal intervening colon. D:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|