The Pharynx and Esophagus

Michael Davis

M. Davis: Department of Radiology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131-5336.

THE PHARYNX

Indications

Reasons for pharyngeal examination by radiologic methods include coughing, choking, or dysphagia; varying degrees of aspiration; nasopharyngeal reflux; a sensation of food “sticking;” a “lump” or tightness in the pharynx; a change in swallowing after head trauma, stroke, or brain tumor; or the inability to handle secretions.

Anatomy and Physiology

Structures observed on the pharyngeal swallow examination include lips, tongue, soft palate, epiglottis, valleculae, pyriform sinuses, and cricopharyngeus muscle. The myriad muscles supporting these structures and their nerve innervation is complex, and a detailed knowledge is required for thorough understanding of swallowing abnormalities.16,17 A normal swallow begins with closed lips and trapping of the barium on the superior aspect of the tongue; this is followed by a muscular wave within the tongue that propels the barium to the oropharynx. The soft palate elevates and closes the nasopharynx, the barium bolus fills the valleculae, and a contraction of the oropharynx occurs with depression of the epiglottis, closure of the glottis, and propulsion of the barium to the hypopharynx. This is followed by contraction of the cricopharyngeus muscle (which is not normally seen except at the end of the swallow) and passage of the barium into the cervical and thoracic portions of the esophagus. All of the steps of the swallowing sequence must occur in an organized, coordinated fashion for a normal swallow to occur. Distortion of the normal anatomy or neuromuscular dysfunction results in swallowing abnormalities.

Examination of the esophagus after a pharyngeal study is often required, especially if the cause of the swallowing abnormality is not clear. Esophageal tumors, strictures, involvement by extrinsic structures, motility disorders, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GRD) may all refer symptoms to the pharyngeal area.

Methods of Examination

The pharynx may be evaluated by routine barium-swallow studies. This is best done with the use of video fluoroscopic swallowing procedures in which the motion dynamics of the swallowing mechanism are recorded. Tape recorders capable of variable speeds and freeze-framing are invaluable. High-density barium (200% weight/volume) gives excellent mucosal coating and outlines the anatomic structures of the mouth and pharynx, which should be examined in frontal and lateral projections.

Patients are usually examined in the upright position, but if a patient is unable to stand, he or she may be examined sitting on the fluoroscopy table footboard; sitting in specialized chairs that can be placed between the fluoroscopic imaging intensifier and the x-ray table; by fluoroscopic C-arm units with the patient in a wheelchair or on a stretcher13; or on an x-ray table with an imaging tube mounted for cross-table lateral imaging and the patient in the supine position. Some investigators recommend that patients be examined in supine position.22 Other investigators recommend oblique projections to augment the standard views.40

Specialized video fluoroscopic swallow examinations are done on patients with severe disabilities from stroke, head injury, penetrating trauma (knife or gunshot wound), cerebral palsy, or other serious acute or chronic conditions. Speech pathologists and occupational therapists are often consulted to evaluate patients with swallowing disorders at the bedside and in the fluoroscopy suite with the radiologist. Thick and thin liquid barium and various foods mixed with barium paste are used to evaluate a patient’s ability to swallow. If liquids and/or solids can be swallowed safely, without aspiration or nasopharyngeal reflux, a dietary regimen can be customized to improve patient’s nutritional status and tube feedings can be discontinued.

RADIOLOGIC PHARYNGEAL ABNORMALITIES

Motor and Neurosensory Disorders

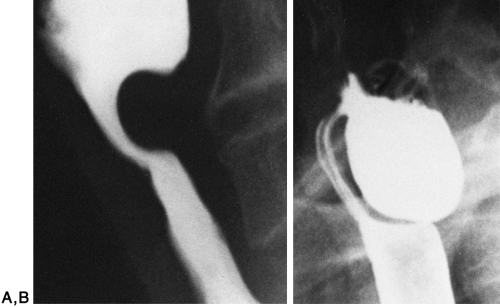

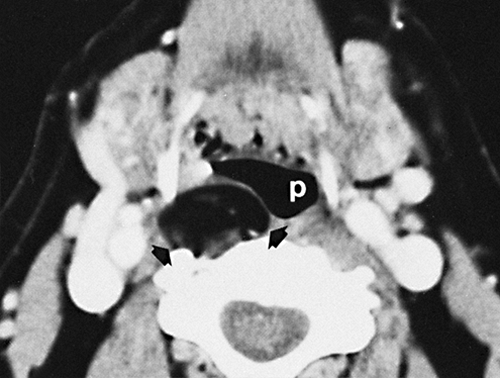

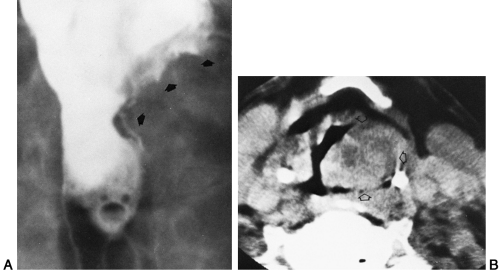

Pooling of barium in the valleculae and pyriform sinuses is a common finding, especially with age, and may be considered a form of paresis, where the neuromuscular function is inadequate to express barium from these structures (Fig. 16-1). Nasopharyngeal reflux of varying degrees and laryngeal aspiration are easily identified. Dysfunction of the cricopharyngeus muscle (upper esophageal sphincter) is also a common abnormality that may occur in older patients or may reflect a protective mechanism in patients with GRD6 (Fig. 16-2A).

Pharyngeal Diverticula and Pouches

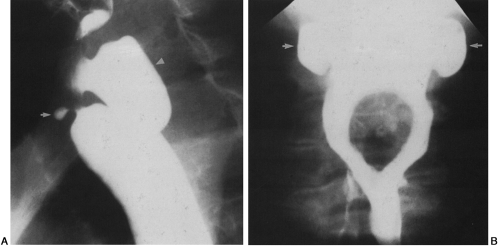

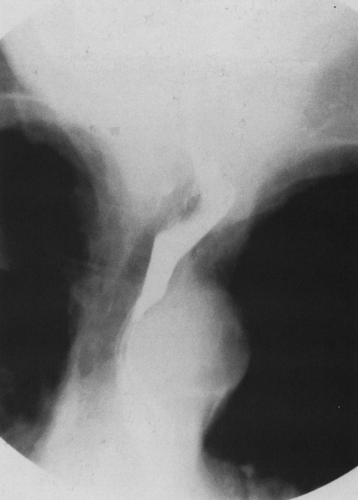

Cricopharyngeal (Zenker’s) diverticula develop just above the cricopharyngeus muscle, protruding posteriorly or posterolaterally, where mucosal herniation through a triangular zone of sparse musculature can occur (Fig. 16-2B). The cause of these diverticula is obscure. They were once thought to be the result of cricopharyngeal muscle spasm or incoordination, but manometric studies showed this to be incorrect. It is now suggested that there may be an association with hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux. These diverticula can grow to be sizeable. They can contain food and saliva that puts the patient at risk for aspiration and potentially leads to bronchitis, bronchiectasis, or lung abscess. Carcinoma is known to occur in a Zenker’s diverticulum. Lateral pharyngeal diverticula occur through a muscle wall weak spot at the pharyngoesophageal junction. (Fig. 16-3A) They are lateral or lateroanterior in location and are usually associated with dysphagia.18 Pharyngeal pouches usually occur bilaterally and tend to be large but are of no clinical significance. (Fig. 16-3B).18

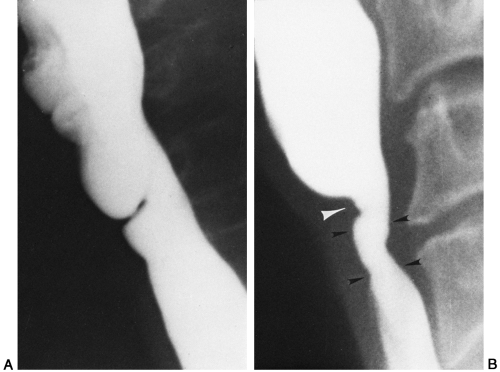

Pharyngeal Webs

Pharyngeal webs are usually singular but may be multiple, and they may involve a portion or all of the circumference of the pharynx at its level of origin (Fig. 16-4A). The presence of cervicoesophageal webs associated with iron deficiency anemia and pharyngeal or esophageal carcinoma, reported in Europe years ago, was referred to as the Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Patterson-Kelly syndrome (Fig. 16-4B.)9 Its decline in recognition coincides with improved diet and treatment of the sideropenic anemia.8

External Impingement

Cervical spine osteophytes are one of the most common causes of external pharyngeal impingement, although other masses such as lymph nodes, tumors, and enlarged thyroids may also deform the pharynx (Fig. 16-5).

Trauma

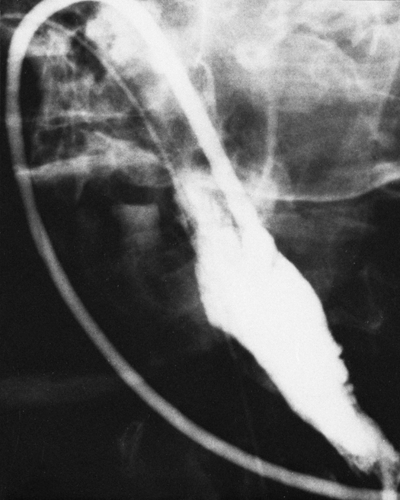

Swallowed sharp foreign bodies, penetrating trauma, caustic agents, and iatrogenic injuries are common causes of pharyngeal trauma (Fig. 16-6).

Inflammation

Epiglottitis shows smooth enlargement on lateral plain films of the pharynx. Enlarged tonsils are occasionally seen on plain film. Candida pharyngitis plaques and herpes pharyngitis ulcers can be seen in barium studies of patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Radiation of pharyngeal tumors can cause inflammation with mucosal

irregularities. Other causes of inflammation are uncommon.

irregularities. Other causes of inflammation are uncommon.

Benign Tumors

Benign tumors are uncommon and are usually composed of existing mesenchymal tissue. As they grow in size, dysphagia becomes the presenting symptom (Fig. 16-7). Epithelial cysts are more common.

Malignant Tumors

The most common malignant tumor of the pharynx is squamous cell carcinoma. People with long-term histories of alcohol and tobacco use are at increased risk for development of this malignancy. Carcinomas may develop at the base of the tongue, epiglottis, pyriform sinuses, valleculae, and palatine tonsils. Enlargement of the tonsils may simulate carcinoma. Double-contrast technique appears to be the best conventional method for diagnosing malignancy where asymmetric or irregular surface mass lesions are detected. Ulcerations and asymmetry caused by the mass lead to the detection of these tumors. If the carcinoma is large enough, single-contrast technique can identify the lesion (Fig. 16-8A). Computed tomography (CT) is helpful, not only in identifying the tumor but also in detecting invasion of adjacent structures (Fig. 16-8B). When examining patients with known tumors of the pharynx and larynx, it is important to examine the esophagus for the presence of a synchronous esophageal carcinoma, which may exist in up to 5% of patients with head and neck cancer.

ESOPHAGUS

Indications

The most common symptoms that lead to examination of the esophagus are heartburn from GRD, followed by difficult (dysphagia) or painful (odynophagia) swallowing. Motility disorders, when severe enough, may give the patient a feeling of chest discomfort or pain. Strictures of the esophagus (usually from GRD) may cause the sensation of food “sticking.”

Anatomy and Physiology

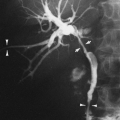

The cervical esophagus begins below the cricopharyngeus muscle (upper esophageal sphincter); at the thoracic inlet it becomes the thoracic esophagus, which then continues to the level of the lower esophageal sphincter, 1 or 2 cm below the diaphragm. The upper esophagus contains striated muscle, whereas the lower portion has smooth muscle. The transition is not abrupt, but rather there is a central segment of varying length which has both elements. In the thorax, the distended esophagus is indented on the left side by the aortic arch and the left mainstem bronchus (Fig. 16-9). With age, a dilated thoracic aortic arch may significantly narrow the lumen of the esophagus, causing dysphagia (Fig. 16-10). As the thoracic aorta elongates and extends into the left chest, it may displace the esophagus, especially if aneurysms have formed. An enlarged left atrium and/or left ventricle shows an extrinsic compression involving the lower anterior esophageal wall (Fig. 16-11). The lower esophageal ring (mucosal ring or B ring) can be seen as a diaphragm-like structure in the distended distal esophagus when a sliding hiatal hernia is present.29 It corresponds to the squamocolumnar mucosal junction. (See Chapter 17, Fig. 17-38A.)

FIG. 16-9. Normal double-contrast esophagram shows indentation by aorta (arrowheads) and left mainstem bronchus (arrow). |

FIG. 16-11. Enlarged left atrium. Double-contrast esophagram shows extrinsic compression of the anterior wall of the lower esophagus. |

As a response to swallowing, the primary wave of esophageal motility that carries the bolus of barium signals the lower esophageal sphincter to open and then close immediately after the swallowed material passes into the stomach. The transport of food and fluid from the mouth to the stomach is aided by gravity in the upright position, but it can be accomplished by peristalsis alone in the recumbent position. Radiologic studies are used to evaluate both anatomic alterations and motility disorders.

Methods of Examination

Plain films of the chest are of limited utility but are indicated in certain situations, such as when an opaque foreign body (e.g., bone, coin) has become lodged in the esophagus. Cervical or mediastinal emphysema is visible on plain films and usually indicates disruption of either the esophagus or a site in the respiratory tract. This finding may lead to a contrast examination. Hiatal hernias are frequently seen on chest radiographs as a mass or air-nfluid level posterior to the heart.

At fluoroscopy, the esophagus may be imaged by the single-contrast, double-contrast, or mucosal relief technique. Usually with overhead filming techniques, only single-contrast examination is done. The single-contrast technique uses a medium-density barium (50% to 60% weight/volume), whereas double-contrast examination employs a heavy or dense barium (200+% weight/volume) in conjunction with an effervescent powder that is given with water just before barium ingestion. In mucosal relief technique the esophagus is filmed after barium has passed and the mucosal folds are collapsed yet remain visible.

Alternatives to barium are the water-soluble solutions of iodinated organic compounds that may be used when perforation of the esophagus is suspected. Ionic water-soluble contrast agents are known to be innocuous in the mediastinum, but it is generally believed that barium in the mediastinum can cause mediastinitis. This belief is based on extrapolated data from laboratory studies that showed barium to cause peritonitis and granuloma formation in the peritoneum. A 1997 report states that barium is safe to evaluate for anastomotic esophageal leaks. Many leaks were found with barium, and no instance of mediastinitis developed. Barium also has better radiopacity than water-soluble contrast agent.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree