Chapter 8 The Pneumoconioses

Many respiratory disorders can be occupationally induced. The most important of these are the pneumoconioses. A pneumoconiosis is a diagnosable disease produced by the inhalation of dust (i.e., particulate matter in the solid phase, excluding living organisms). Mineral dust can be classified as fibrogenic, such as asbestos and silica, or inert, such as iron, tin, or barium. The metal dusts include beryllium and cobalt, which are associated with granulomatous pneumonitis and giant cell pneumonitis, respectively (Table 8-1). Most pneumoconioses produce diffuse opacities on the chest radiograph that are similar to those seen in other interstitial lung disorders.

| Agent | Examples | Disorders |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral dusts | Asbestos Silica Coal | Pneumoconioses |

| Metal dusts | Iron Tin Barium | “Inert dust” pneumoconioses |

| Metal dusts | Beryllium Cobalt | Granulomatous pneumonitis Giant cell pneumonitis |

| Biologic dusts | Spores Mycelia Bird droppings | Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (allergic alveolitis) |

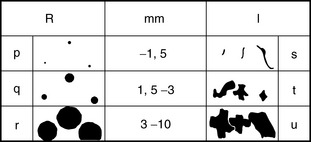

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION CLASSIFICATION OF PNEUMOCONIOSES

The International Labour Organization (ILO) classification of the radiographic appearances of the pneumoconioses is a standardized, internationally accepted system used to codify the radiographic changes in the pneumoconioses in a reproducible manner (Box 8-1). The advantage of the system is that it provides graphic and morphometric terms to describe diffuse lung patterns. The classification includes conventions of small, rounded (nodules) and small, irregular (linear and reticular) opacities (Fig. 8-1). The small, rounded opacities are classified according to the approximate diameter of the predominant opacity: p (up to 1.5 mm in diameter), q (1.5 to 3 mm in diameter), and r (3 to 10 mm in diameter). Small, irregular opacities are classified on the basis of thickness and appearance: s (fine, up to 1.5 mm thick), t (medium, 1.5 to 3 mm thick), and u (coarse or blotchy, 3 to 10 mm thick).

Box 8-1 International Labour Organization (ILO) Classification of Pneumoconioses

PROFUSION (SEVERITY)

LL, left lower; LM, left middle; LU, left upper; RL, right lower; RM, right middle; RU, right upper.

SILICOSIS

General Description

Silicosis (Box 8-2) is a fibrotic disease of the lungs caused by inhalation of dust containing free crystalline silica or silicon dioxide. It is the predominant constituent of the earth’s crust. Silica dust may be encountered in almost any mining, quarrying, or tunneling operation. Occupations at risk therefore include the mining of heavy metals, such as gold, tin, copper, silver, nickel, and uranium, and to a lesser extent, coal mining; the pottery industry; sandblasting; foundry work; and stone masonry. Silicosis is usually a chronic, slowly progressive disease that occurs with a latency period of at least 20 years.

Simple Silicosis

Simple silicosis (Box 8-3) has no symptoms and is not associated with any significant changes in pulmonary function.

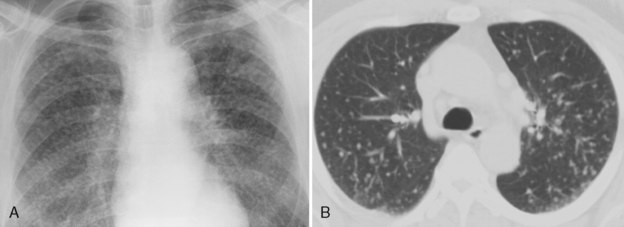

Radiographic Findings

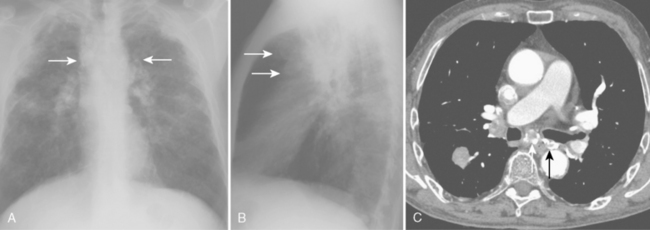

Classic radiographic findings of simple silicosis consist of multiple nodules or small, rounded opacities 1 to 10 mm in diameter (Fig. 8-2A). Larger nodules often predominate, and they typically are distributed more in the upper lung zones. Occasionally, the nodules calcify. Enlargement of lymph nodes is common and may precede the appearance of diffuse nodularity. Calcification of the periphery of hilar and mediastinal nodes may occur. This is called eggshell calcification, and it has a characteristic appearance (Fig. 8-3).

Computed Tomography Findings

Because silicosis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis exhibit a nodular pattern, conventional computed tomography (CT) and high-resolution CT (HRCT) should be used. CT clearly depicts the characteristic nodules in patients with simple silicosis, and it is more sensitive in the detection of these nodules than conventional radiographs (see Fig. 8-2B). Conventional 10-mm CT is preferred because the thin sections in HRCT may lead to underestimation of the prevalence of nodules, and it is often difficult to differentiate small nodules from normal pulmonary vessels. However, conventional scans should be supplemented with thin-section HRCT to depict fine parenchymal detail. These scans can be limited and performed at preselected levels. The study should include at least three slices through the upper lung zones, where nodules of silicosis predominate.

Complicated Silicosis

Characteristics

Complicated silicosis (Box 8-4) is characterized by the appearance of one or more areas in which the silicotic nodules have become confluent (>1 cm in diameter). These areas may contain obliterated blood vessels and bronchi. Complicated silicosis is associated with symptoms and often with disability.

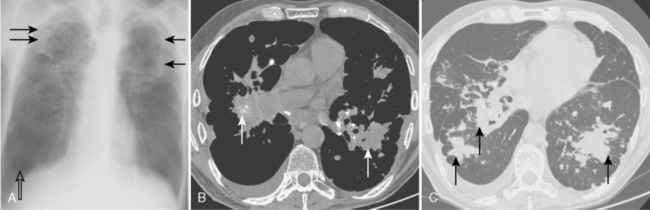

Radiographic Findings

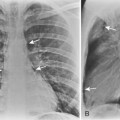

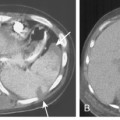

On the chest radiograph, the opacities of complicated silicosis appear in the middle zone or in the periphery of the lung in the upper lobes (Fig. 8-4A). They tend to migrate to the hilum, leaving overinflated emphysematous lung tissue in the surrounding lung, particularly at the bases. The more extensive the progressive massive fibrosis, the less the apparent the nodularity in the remaining lungs.

As conglomeration develops, the lungs gradually lose volume, and cavitation of the masses may result from ischemic necrosis. In this setting, tuberculosis or infection with atypical mycobacteria may supervene. Superimposed tuberculosis may be difficult to detect radiographically; findings such as cavitation of conglomerate masses, pleural reaction at the apices, or other rapid radiographic changes are suggestive (Fig. 8-5). The diagnosis of supervening tuberculosis, however, is bacteriologic rather than radiologic.

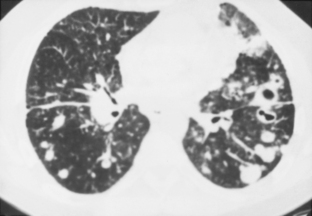

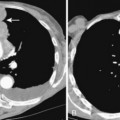

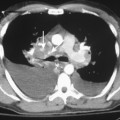

Computed Tomography Findings

CT features are similar to those seen on standard radiographs, but coalescence of nodules and the development of conglomerate masses can often be detected at an earlier stage (see Fig. 8-4B and C). Conglomerate masses of complicated silicosis can be associated with disruption of normal vessels and bulla formation (Fig 8-6). CT is better at revealing gross disruption of the pulmonary parenchyma in the upper lung zones in complicated disease.

Accelerated Silicosis and Acute Silicosis

Accelerated Silicosis

Accelerated silicosis (Box 8-5) often occurs after exposure to high concentrations of silica over a relatively short period, usually a few years. The radiographic and CT features are similar to those in simple silicosis.

Acute Silicosis

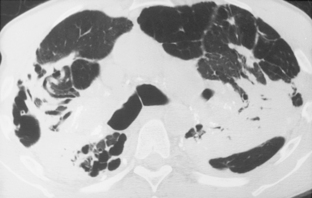

Acute silicosis or silicoproteinosis (see Box 8-5) usually occurs as a consequence of exposure to large quantities of fine particulate silica in enclosed spaces over a period of a few weeks. Pathologically, the alveoli are filled with an eosinophilic and lipid-rich exudate, which is periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain positive. The disease rapidly progresses, and death is caused by respiratory failure.

Caplan’s Syndrome

Silicosis is associated with increased prevalence of several connective tissue diseases, including progressive systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Caplan’s syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Caplan’s syndrome (Box 8-6) consists of large, necrobiotic nodules (i.e., rheumatoid nodules) superimposed on a background of simple silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (Fig. 8-7). It is a manifestation of rheumatoid lung disease, and it is seen more commonly in coal worker’s pneumoconiosis than in silicosis. The nodules are 0.5 to 5 cm in diameter, and they may cavitate and calcify. Although they most often develop concomitantly with the joint disease, their formation may precede the onset of arthritis by months or years.

COAL WORKER’S PNEUMOCONIOSIS

Simple Coal Worker’s Pneumoconiosis

Causes and Pathology

Simple coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (Box 8-7) results from the retention of coal dust alone. Pathologically, the hallmark of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis is the coal macule. It consists of aggregations of dust around dilated respiratory bronchioles. Fibrosis is minimal. Simple coal worker’s pneumoconiosis is not associated with any significant functional impairment, and workers are usually asymptomatic.

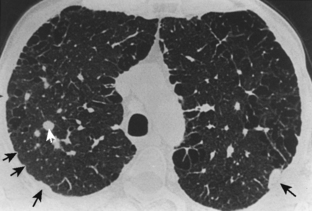

Computed Tomography Findings

The CT findings for simple coal worker’s pneumoconiosis include parenchymal and subpleural micronodules (<7 mm in diameter) (Fig. 8-8). The nodules show an upper-zone and right-sided predominance. When they occur in the subpleural zones, they may become confluent, forming pseudoplaques, which consist of subpleural focal linear areas of increased attenuation that are less than 7 mm wide. Larger nodules that are between 7 and 20 mm in diameter can be seen scattered on a background of micronodules.