The Small Intestine

Michael Davis

M. Davis: Department of Radiology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131-5336.

THE SMALL BOWEL

Indications

The presence of an abdominal mass or the suspicion of partial small-bowel obstruction often leads to examination of the small bowel. Unexplained diarrhea, malabsorption, and unexplained intestinal bleeding are also indications. Abdominal pain or tenderness may justify a small-bowel examination. In most cases, because the frequency of a symptomatic abnormality is much less in the small intestine than in the upper gastrointestinal tract and colon, a search is made first for diseases of these areas before the small bowel is studied.

Anatomy

The jejunum and ileum together are termed the mesenteric small intestine. Because the small bowel is not fixed within the peritoneal space, considerable shift of any individual segment can occur. The mucosal folds in the small intestines (also referred to as valvulae conniventes or plicae circulares) are normally 1 to 2 mm in width and regularly spaced. In the ileum, the folds become less regularly spaced and fewer in number, although fold width remains the same. At small-bowel follow-through, the jejunum is as much as 3 cm in diameter and the ileum 2.5 cm.

Physiology

As the chyme goes through the small intestine, the processes of digestion and absorption occur. Reabsorption of bile salts and water are important functions of the ileum. Motility of the small bowel has two active phases. In the churning phase, distal transport of chyme is random. The second phase is related to the migrating motor complex, the pacemaker of the bowel, which starts its activity in the stomach and gradually sweeps through the entire small intestine. It is extremely effective in delivering all the material in the small bowel to the colon. There is also a quiescent phase in which no motor activity occurs. Contractile activity of the small intestine is governed by the integration of myogenic, neural, and biochemical controls.28

Methods of Examination

Barium Studies

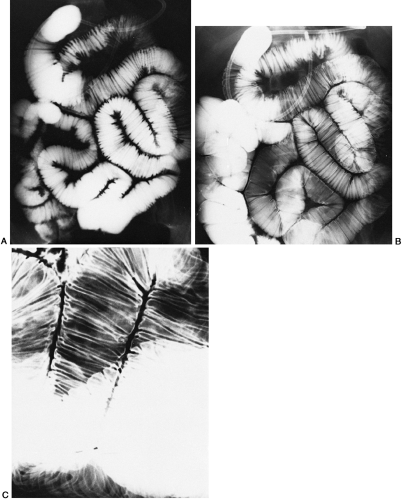

The conventional method of studying the small bowel with barium sulfate is to extend the examination of the stomach and duodenum. Ordinarily, the patient drinks a total of 480 to 600 ml of a medium-density barium (50% to 60% weight/volume). Overhead and fluoroscopic spot films of the small bowel are done at intervals of 20 to 30 minutes until the colon fills. During fluoroscopy, the small bowel is manipulated to observe the mobility of the loops and to detect any abnormal focal process such as an adhesion, mass, or hernia. This cycle is repeated until barium is seen in the colon when fluoroscopic spot films of the terminal ileum are done (Fig. 18-1).

Thickening, straightening, dilatation, nodularity, or a combination of these fold patterns is found in several focal and diffuse small-bowel conditions. A precise diagnosis usually depends on correlation with clinical and laboratory findings. Biopsy may be necessary for final confirmation, but at times the correlation of the clinical findings and small-bowel studies results in a reliable diagnosis.

Enteroclysis

In this technique, a nasointestinal tube is placed with the tip at or preferably just beyond the duodenal-jejunal junction, and barium is infused at a rate of about 100 ml/minute, which far exceeds the rate of gastric emptying. With this method, there is no overlap of the stomach on the small bowel, and there is complete control of the flow of barium during the examination. Infusion of the barium into the small intestine can quickly overcome restrictions such as masses or adhesions that normal peristalsis overcomes only slowly. In addition, methylcellulose may be infused after the barium to provide a “see-through” or double-contrast

effect for better visualization of the mucosal folds. During the filling of the bowel, each segment can be observed with the fluoroscope. This small-bowel enema (enteroclysis) has the disadvantages of increased patient discomfort associated with nasal intubation and, usually, greater radiation exposure. There is disagreement regarding the efficacy of the conventional peroral small-bowel examination versus enteroclysis (Fig. 18-2).27 The dedicated or detailed small-bowel examination and enteroclysis show comparable sensitivities for common disorders. Enteroclysis better visualizes focal lesions and partial bowel-obstructive processes such as adhesions.26

effect for better visualization of the mucosal folds. During the filling of the bowel, each segment can be observed with the fluoroscope. This small-bowel enema (enteroclysis) has the disadvantages of increased patient discomfort associated with nasal intubation and, usually, greater radiation exposure. There is disagreement regarding the efficacy of the conventional peroral small-bowel examination versus enteroclysis (Fig. 18-2).27 The dedicated or detailed small-bowel examination and enteroclysis show comparable sensitivities for common disorders. Enteroclysis better visualizes focal lesions and partial bowel-obstructive processes such as adhesions.26

Peroral Small-Bowel Examination With Pneumocolon

Examination of the ileocolic area may be enhanced by the introduction of air into the colon via the rectum as barium arrives at the ileocecal area.

Reflux Small-Bowel Examination

During barium enema examination, reflux into the small intestine through an incompetent ileocecal valve can opacify the small intestine. The entire small bowel may be filled this way, usually with some discomfort to the patient (Fig. 18-3).

Water-Soluble Contrast Studies

The use of water-soluble contrast agents to examine the small bowel is indicated if perforation is suspected; in all other instances its use compromises the examination.7 The dilution of the material that occurs in the fluid-filled bowel and the osmotic effect of the hypertonic solution interfere with the identification of pathologic anatomy. Water-soluble material is suitable as a radiopaque marker to determine passage of intestinal contents to the colon. It is also used effectively as a method to opacify the intestine for computed tomographic (CT) scanning, although it has no detectable advantage over dilute barium sulfate.

In the presence of a palpable abdominal mass, examination with either ultrasonography or CT is generally more informative and is performed without earlier barium study.

Nuclear medicine studies are of value for locating Meckel’s diverticula that contain acid-secreting cells. The localization of small-bowel bleeding is another contribution made by isotype studies.

Alternative Nonradiologic Methods

Small-bowel push (external stomach compression) enteroscopy can potentially intubate the intestine up to 90 cm in depth, withan average depth of 45 cm past the ligament of Treitz. This technique can be used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes that include polypectomy, stricture dilatation, treatment of bleeding lesions with lasers, and treatment of problematic nasojejunal tubes and other enteral tubes.6

Sonde enteroscopy uses a scope 250 cm in length and 5 mm in diameter. It provides the only method whereby the contents and mucosa of all or almost all the small intestine can be viewed directly.15

Endoscopic enteroclysis is another alternative for investigating the small intestine. The enteroclysis examination is done through the endoscope.1

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Tubulation Defects

As in the duodenum, atresia and stenosis of the small bowel can occur. These lesions may be multiple and diffuse or localized. Symptoms usually occur immediately after birth, and plain films of the abdomen show dilated, fluid-filled small bowel. Barium studies are often unnecessary.

Rotation Anomalies

The herniation of sac-encased intestine through a defect in the anterior abdominal wall at the level of the base of the umbilical cord (omphalocele) is one manifestation of lack of proper fetal development. Because this is such a visible process, radiographic studies are unnecessary. This anomaly may be identified in utero by ultrasonography.

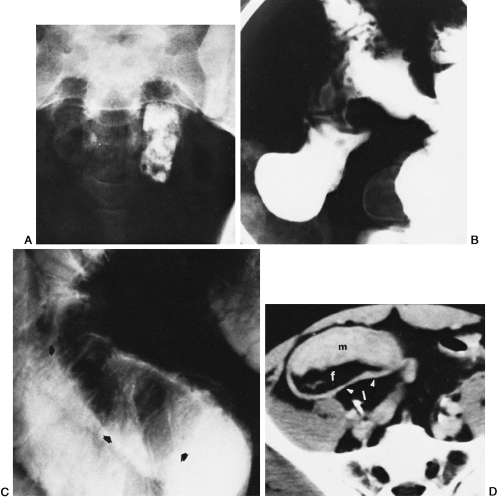

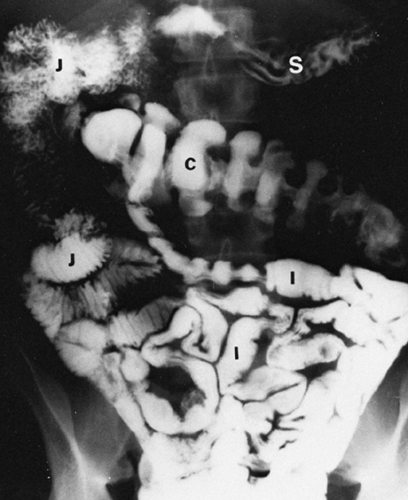

Nonrotation can result in location of the entire small bowel on the right side of the abdomen and the entire colon on the left. Frequently, the third and fourth portions of the duodenum are not fixed retroperitoneally and also are on the right side. There may be no associated symptoms (Fig. 18-4).

FIG. 18-4. Nonrotation. S, stomach; J, jejunum; I, ileum; C, colon (see FIG. 18-1). The jejunum is normally in the left-upper quadrant (LUQ), the ileum in the midabdomen and the right-lower quadrant, and the right colon in the right-lower quadrant. |

Midgut volvulus is a condition that is symptomatic. It occurs as a complication of a mesentery that is unduly long, allowing excessive mobility of the intestine, possibly complicated by infarction of the bowel. Peritoneal bands or veils

that compromise the duodenal lumen also may be part of this anomaly. Barium studies can be done if the plain films do not provide enough justification for an exploratory laparotomy (Fig. 18-5).

that compromise the duodenal lumen also may be part of this anomaly. Barium studies can be done if the plain films do not provide enough justification for an exploratory laparotomy (Fig. 18-5).

Duplication Cysts and Diverticula

Duplication cysts can occur at any place along the bowel. Because they are fluid-filled, ultrasonography is particularly effective in diagnosis. Multiple diverticula of the small bowel may occur and may not be symptomatic until bacterial overgrowth in these pockets creates enough bile salt deconjugation or vitamin B12 consumption to cause the classic symptoms of diarrhea, steatorrhea, and megaloblastic anemia. The diverticula are readily visualized with barium. It is important to understand that occasional jejunal and ileal diverticula are seen without causing symptoms (Fig. 18-6).

FIG. 18-6. Diverticulosis of small bowel; arrowheads identify several of the many diverticula present. |

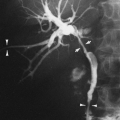

Meckel’s diverticulum deserves special attention because of its frequency and propensity to cause symptoms. This diverticulum represents the persistence of the omphalomes

enteric duct. It is present in up to 4% of the population and most often is totally asymptomatic. However, it may cause problems as a site of volvulus or intussusception with resultant small-bowel obstruction. Inflammation and a perforation similar to that seen with vermiform appendix may occur. The diverticulum may contain acid-secreting cells that may cause ulceration of the sensitive ileal mucosa and subsequent hemorrhage. Enteroclysis is the only barium method that has had consistent success in finding these ileal diverticula (Fig. 18-7).22 Technetium studies are helpful in patients who are bleeding and have ectopic gastric mucosa in the diverticulum. Rarely, the diverticula are very large, and sometimes they contain calcified enteroliths.

enteric duct. It is present in up to 4% of the population and most often is totally asymptomatic. However, it may cause problems as a site of volvulus or intussusception with resultant small-bowel obstruction. Inflammation and a perforation similar to that seen with vermiform appendix may occur. The diverticulum may contain acid-secreting cells that may cause ulceration of the sensitive ileal mucosa and subsequent hemorrhage. Enteroclysis is the only barium method that has had consistent success in finding these ileal diverticula (Fig. 18-7).22 Technetium studies are helpful in patients who are bleeding and have ectopic gastric mucosa in the diverticulum. Rarely, the diverticula are very large, and sometimes they contain calcified enteroliths.

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS, INFESTATIONS, AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Extrinsic Agents

Because the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum are buffers for damaging extrinsic agents, the small bowel is largely spared.

Floxuridine, a pyrimidine used for treatment of carcinoma of the colon and rectum that has metastasized, can be infused into the hepatic arterial system or systemically by intravenous infusion. This drug causes severe diarrhea. Radiographic findings include thickening of the mucosal folds with effacement or segmental narrowing, usually in the terminal

ileum. Radiographic findings are reversible when the drug is discontinued.19

ileum. Radiographic findings are reversible when the drug is discontinued.19

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may cause diaphragm-like strictures in the small intestine.21 The findings can resemble those of Crohn’s disease.20

Flucytosine is an antifungal drug used for the treatment of cryptoccocal meningitis and other fungal diseases. Ulcerative enterocolitis may develop in patients receiving this drug. Radiographic findings include ulcerations, strictures, and thickening of the bowel wall.32

Radiation enteropathy of the small bowel is less common now because CT can better estimate the tumor mass volume. This results in more accurate radiotherapy doses and less radiation to nontumor tissue.17 Radiation effects occur late, with stricture and intestinal obstruction being the clinical manifestations. Early radiographic findings include edema and wall thickening, followed by narrowing, fixation, and sometimes kinking (Fig. 18-8).

Specific Organisms

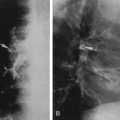

Intestinal parasites are extremely common worldwide. The mature ascaris (round) worm can easily be identified within the small bowel as a round or elongated filling defect in the bowel lumen (Fig. 18-9). The same is true with a tapeworm infestation (Fig. 18-10). Campylobacter and Giardia

lamblia can cause an acute illness with recognizable small-bowel edema,4 usually in the upper jejunum (Fig. 18-11). In its chronic phase, giardiasis may not show any radiographic abnormalities. Strongyloides stercoralis can cause severe small-bowel symptoms and radiographic findings. These findings—medema, nodularity, and stricture—mare most prominent in the jejunum (Fig. 18-12). The radiographic findings mimic those of Crohn’s disease and are chronic in nature.

lamblia can cause an acute illness with recognizable small-bowel edema,4 usually in the upper jejunum (Fig. 18-11). In its chronic phase, giardiasis may not show any radiographic abnormalities. Strongyloides stercoralis can cause severe small-bowel symptoms and radiographic findings. These findings—medema, nodularity, and stricture—mare most prominent in the jejunum (Fig. 18-12). The radiographic findings mimic those of Crohn’s disease and are chronic in nature.

FIG. 18-10. Taenia saginata. The beef tapeworm creates thin, longitudinal filling defects that are most easily seen in the ileum. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree