The Stomach and Duodenum

Michael Davis

M. Davis: Department of Radiology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131-5336.

THE STOMACH AND DUODENUM

Indications

Symptoms of epigastric pain raise the possibility of peptic ulcer disease and lead to an examination of the stomach and duodenum. Hematemesis or melena is also a strong indication. Subacute or chronic nausea and vomiting raises the possibility of an obstructive lesion. A palpable mass in the upper abdomen may involve the stomach. Weight loss and anorexia are less specific symptoms but can occur with gastric cancer. All intra-abdominal structures can be seen by computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound imaging. Nevertheless, barium and other contrast materials remain invaluable for detection of alimentary tract diseases.

Anatomy

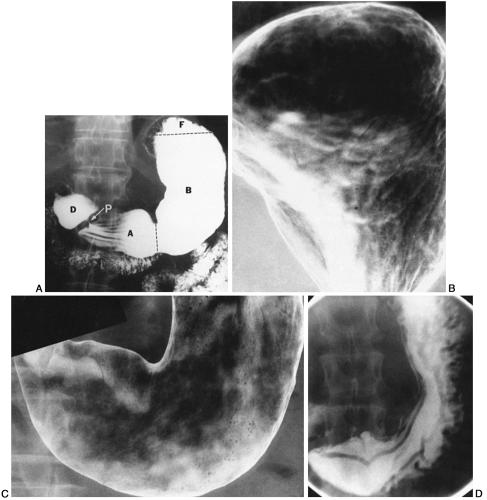

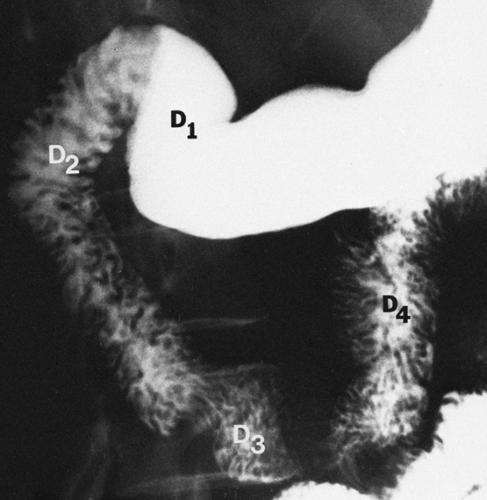

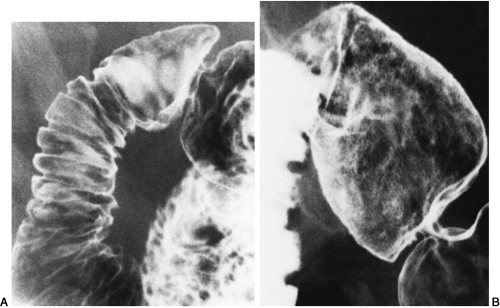

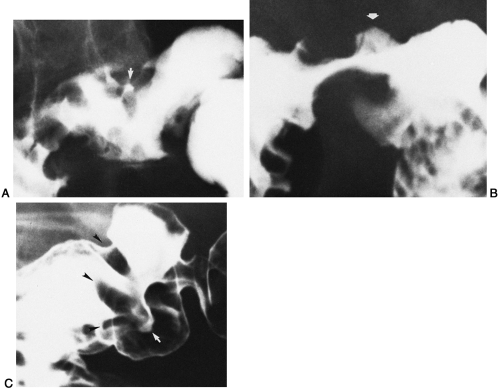

The stomach and duodenum are divided into segments that do not have sharply defined margins. The terms gastroesophageal junction (cardia), fundus, body, antrum, pyloric canal, and greater and lesser curvature are commonly used to identify the position of gastric lesions (Fig. 17-1). The parts of the duodenum are described as the bulb and the second, third, and fourth portions (Fig. 17-2). The stomach itself varies considerably in size and position. The asthenic habitus is associated with a vertically oriented body and antrum, with the stomach often dipping into the pelvis. Stouter patients have stomachs with a transverse orientation. The duodenum has few anatomic variations, mainly because most of it is retroperitoneal and fixed in position. Occasionally there is some redundancy in the postbulbar area. The mucosal folds in the duodenum are relatively constant in size (Fig. 17-3), but there is a large range in the size of normal gastric folds. Gastric folds are particularly prominent along the greater curvature and in the fundus (see Fig. 17-1D).

Physiology

The primary digestive process begins in the stomach, where the secretion of acid and pepsin creates an environment for both protein breakdown and peptic ulcer disease. Stomach content is carried to the duodenal bulb, where the pH becomes more neutral. The stomach and duodenum also have endocrine-type activity, with gastrin released from cells in the antrum and cholecystokinin released from the duodenal cells. Gastric motility is a complex process, but it can be divided into a churning phase and an emptying function. The stomach empties fluids much more rapidly than solids.

Methods of Examination

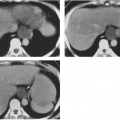

The fluoroscopic-radiographic examination of the upper GI tract with barium sulfate suspension has been standard for years. The single-contrast examination uses 6 to 10 oz of medium-density barium (50% to 60% weight/volume) (see Fig. 17-1A, D). Effervescent powders are given in conjunction with heavy or dense barium (200+% weight/volume) to create the double-contrast examination (see Fig. 17-1B, C). The double-contrast method provides improved visualization of the mucosal surface. This is particularly important for finding shallow erosions and small polypoid lesions. Some investigators employ the biphasic examination, which encompasses aspects of both the single- and double-contrast techniques.20,30 Water-soluble contrast material is used if perforation of the stomach or duodenum is suspected. The use of glucagon in small doses to inhibit motility temporarily can be helpful. 9,22 CT and ultrasonography may demonstrate a large gastric mass quite well, but they are not considered the prime modes of detection of gastroduodenal lesions. CT is particularly of value in the preoperative staging of malignant lesions.25,37

Alternate Nonradiologic Methods

Fiberoptic endoscopy is a magnificent method for visualizing the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum. Repeated studies show increased sensitivity compared with the radiologic method. In some parts of the world endoscopy has replaced the radiologic method as the primary examination. In others the disparity in costs for the two studies has kept the radiologic method primary.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Failures of Tubulation

Duodenal atresia is discovered quickly after birth. Upright plain films showing air-nfluid levels in the stomach and duodenum and no gas in the rest of the intestine are characteristic of obstruction, but similar findings may also be seen in infants with the duodenal bands associated with malrotation and with volvulus of the small bowel. It usually is not necessary to do contrast studies under

these circumstances. A web as a manifestation of incomplete tubulation can manifest itself in the stomach as an antral diaphragm; this may not be symptomatic. In the duodenum an almost complete web can produce a complicated roentgenographic appearance. The web may balloon caudally like a wind sock; this appearance has been given the name intraluminal diverticulum. The web is primary, and the diverticulum develops later.

these circumstances. A web as a manifestation of incomplete tubulation can manifest itself in the stomach as an antral diaphragm; this may not be symptomatic. In the duodenum an almost complete web can produce a complicated roentgenographic appearance. The web may balloon caudally like a wind sock; this appearance has been given the name intraluminal diverticulum. The web is primary, and the diverticulum develops later.

Dextroposition

The stomach may be on the right, associated with total situs inversus. Rarely, there is dextroposition of the stomach only or situs inversus of the abdominal viscera only.

Duplication and Diverticula

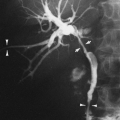

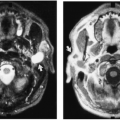

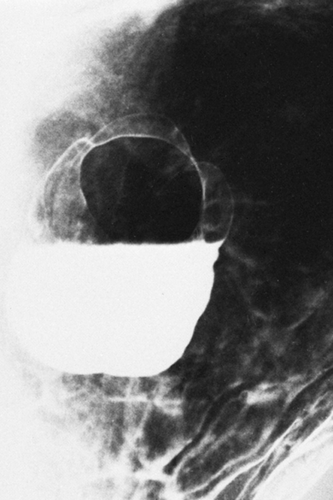

Diverticula of the cardia of the stomach that arise posteriorly are the only common gastric diverticula (Fig. 17-4). Perhaps these are related to the multiple stomachs of the ruminants. Gastric and duodenal duplication cysts are rare (Fig. 17-5). Duodenal diverticula are extremely common, particularly in the inner aspect of the descending portion, and are rarely of any pathologic significance (Fig. 17-6).

FIG. 17-4. Double-contrast examination of the proximal stomach where a large wide-mouth diverticulum is present. Barium is pooling in the dependent portion of the diverticulum. |

FIG. 17-5. Single-contrast examination of the duodenal bulb demonstrates a duplication cyst (arrows). S, distal stomach. |

Congenital Rests

Aberrant pancreatic tissue can occur in the gastric antrum and proximal duodenum. Although it has the configuration of an intramural mass, it may have a small central depression at the site of a miniature excretory duct (Fig. 17-7).

Microgastria

A very small midline stomach may be found, but this is rare. Microgastria usually is associated with other congenital anomalies. Gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal dilatation are often present.

Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Persistent vomiting in an infant at the age of 3 to 5 weeks suggests the possibility of pyloric stenosis. At times the hypertrophied pyloric muscle can be palpated; it can also be visualized ultrasonographically. The standard method of diagnosis is

with oral barium sulfate. The diagnosis rests on seeing an elongated pyloric canal (Fig. 17-8), often with thick muscle bulging into the base of the duodenal bulb. A delay in gastric emptying is not adequate for diagnosis because it can occur normally. Rarely, pyloric stenosis is found in an adult; in these cases it must be differentiated from circumferential antral carcinoma.

with oral barium sulfate. The diagnosis rests on seeing an elongated pyloric canal (Fig. 17-8), often with thick muscle bulging into the base of the duodenal bulb. A delay in gastric emptying is not adequate for diagnosis because it can occur normally. Rarely, pyloric stenosis is found in an adult; in these cases it must be differentiated from circumferential antral carcinoma.

Annular Pancreas

Fusion of the ventral and dorsal pancreas so that it completely surrounds the duodenum is rare, but if it does occur it may cause partial or complete duodenal obstruction Fig. 17-9).

GASTRITIS, DUODENITIS, AND ULCER DISEASE

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is the causal agent of chronic gastritis and the primary cause in gastric and duodenal peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori also appears to be strongly linked to gastric carcinoma and primary gastric lymphoma. Genetic, environmental, nutritional, and lifestyle factors, when linked with H. pylori, produce a wide spectrum of disease in the stomach and duodenum.10,11

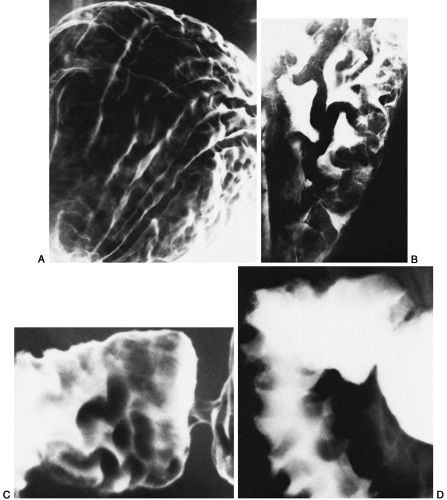

Gastric Fold Enlargement, Mucosal Nodularity, and Antral Narrowing

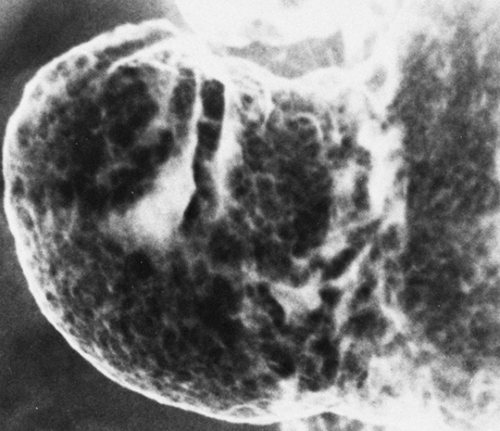

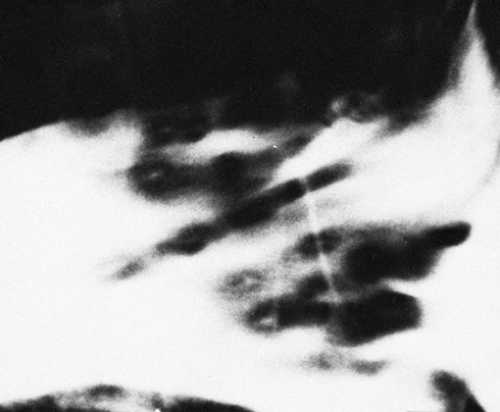

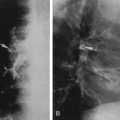

The earliest changes of peptic disease in the stomach and duodenum may be hypertrophy or enlargement of folds Fig. 17-10). In some instances the mucosal surface pattern can become irregular Fig. 17-11). Large gastric folds with or without ulceration and/or erosions are the best predictors of H. pylori infection. 24,35 Antral nodularity and narrowing are also indicative of H. pylori gastritis.5

Erosions

Gastric and duodenal erosions are the most minimal manifestations of peptic ulcer disease that can be detected. Sometimes there is a small mound of associated edema; in other cases, only the erosion is present. The single contrast technique using compression is particularly effective in demonstrating these small lesions (Fig. 17-12). Such erosions can be responsible for both epigastric pain and bleeding. Because they are quite small, they heal quickly with treatment.

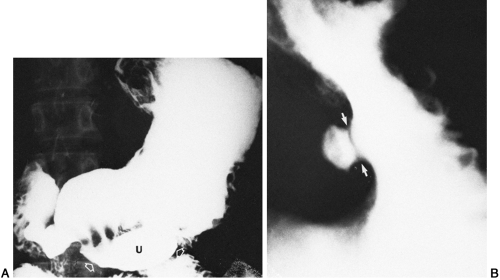

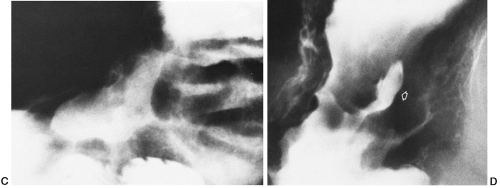

Ulcers

It is difficult to define the difference between an ulcer and an erosion, and indeed the spectrum is continuous. Ulcers are erosions that have penetrated more deeply into the mucosa, and ordinarily their diameter is greater than that of other erosions. The increase in size allows more ready radiologic detection. Ulcers, like erosions, may be seen anywhere in the stomach or proximal duodenum, but they are most common in the antrum, pyloric canal, and duodenal bulb (Figs. 17-13 and 17-14).4 The lesser curvature of the body of the stomach is also a prevalent site, but ulcers may occur on the greater curvature as well. Very large benign ulcers found on the greater curvature are often caused by ingestion of drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory compounds. The major sign is the ulcer crater, which usually projects beyond the gastric wall. There is often a smooth rim of edema at the edge of the crater (Hampton line). Mucosal folds are often observed extending to the rim or edge of the crater. Greater curvature ulcers are more varied in appearance and may resemble malignant lesions; in such cases, careful follow-up or biopsy is indicated. The radiologic method is valuable not only for detecting these ulcers but also for evaluating the effects of treatment. Patients with gastric ulcers who have H. pylori gastritis have a higher rate of gastric ulcer recurrence.21

Perforated Ulcers

A gastric or duodenal ulcer, often with few premonitory symptoms, may perforate into the peritoneal space. The symptoms then become quite dramatic. Plain films are indicated in this situation. Upright films show free air under the diaphragm. If the upright position cannot be achieved, a decubitus film of the abdomen with the patient’s

left side down demonstrates air between the liver and the right lateral peritoneum.

left side down demonstrates air between the liver and the right lateral peritoneum.

Scarring

Although erosions leave no demonstrable scar, medium and large ulcers may heal with a considerable deformity. In the stomach, gastric folds radiating toward a central point are indicative of a healed ulcer Fig. 17-15

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree