Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection

Paul D. Campbell Jr.

Edward H. Herskovits

Both thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection may constitute surgical emergencies, yet their diagnostic evaluations are fraught with difficulty due to the lack of specificity of clinical findings. Radiologic methods therefore assume a critical role in the evaluation for these conditions.

Etiology and Epidemiology.

Aortic aneurysm has a prevalence of approximately 10% in autopsy series. Morphologic types include saccular, fusiform, dissecting, false, and sinus of Valsalva. Although arteriosclerosis (saccular and fusiform aneurysms) is the major predisposing factor, trauma (false aneurysm), aortitis (e.g., syphilis, Takayasu arteritis), Marfan’s syndrome, and infection (mycotic aneurysm) should be considered. The risk of aneurysm rupture is directly related to the wall tension, which in turn is a function of the diameter. In practice, the threshold for surgical repair is a diameter of 5 cm or greater, because these aneurysms have at least a 10% chance of rupture per year. A patient with chest pain and an aortic aneurysm must be considered to have a ruptured aneurysm until proved otherwise, and may require emergent surgical repair.

Thoracic aortic dissection is the most prevalent emergency involving the aorta; if untreated, it carries a mortality of approximately 70% during the first 2 weeks, and approximately 90% during the first 3 months; treatment may decrease the 3-month mortality to approximately 30%. The most common predisposing factors are hypertension and Marfan’s syndrome.

Almost all dissections begin as an intimal tear in one of two locations where the aorta is relatively fixed: (1) the ascending aorta 2-5 cm above the aortic valve (the most common site) and (2) the descending aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Two classification systems are used to describe thoracic aortic dissection: the DeBakey and the Stanford systems. In the DeBakey system, type I dissections involve the ascending and descending aorta, type II dissections involve only the ascending aorta, and type III dissections involve only the descending aorta. In the Stanford system, type A refers to a dissection with any ascending aortic involvement, and type B refers to involvement limited to sites distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Dissection involving the aorta proximal to the arch (DeBakey types I and II, Stanford type A) is more worrisome, for it may lead to occlusion of the great vessels or coronary arteries, aortic insufficiency, and pericardial tamponade. For this reason, these dissections are treated surgically. Conversely, dissection restricted to that portion of the aorta distal to the aortic isthmus (DeBakey type III, Stanford type B) is usually treated medically with antihypertensive therapy, unless the renal arteries or other arterial branches are compromised. Involvement of the coronary arteries occurs in 10-20% of patients with thoracic aortic dissection. In the aorta, blood flow often dissects the portion of aortic wall where flow is greatest, that is, where the radius of curvature is greatest, which is the side of the aorta that is farthest from the heart. Therefore, dissections tend to be located anteriorly in the ascending aorta, superiorly at the level of the arch, and posteriorly and to the left in the descending aorta. Therefore, the left renal artery is in greater danger of occlusion by a dissection involving the descending aorta than is the right renal artery. The opposite would be true in a person with right aortic arch.

Symptoms and Signs.

Symptoms include chest pain, particularly severe in patients with dissection, which may be indistinguishable from angina. The pain is usually of sudden onset, may radiate to the upper back, or to the lower back and flank. Physical examination of patients with aneurysm is often unrevealing, but in patients with dissection there may be an absent carotid pulse, a diastolic murmur, or difference between the blood pressures of the upper extremities or between the upper and lower extremities.

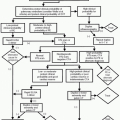

Protocol.

Standard upright posteroanterior (PA) chest radiographs are much preferable to supine anteroposterior (AP) radiographs, but may not be possible due to the patient’s condition. Chest radiography is highly sensitive for detecting aortic aneurysm, moderately sensitive for detecting aortic dissection from trauma, and nonspecific for either, thereby necessitating further evaluation when the radiograph is abnormal or when clinical suspicion is high.

Possible Findings.

Relevant findings in the setting of aneurysm or dissection include the following:

Widened mediastinum, especially if it increases with time. In cases of trauma, mediastinal widening is caused by injury and bleeding of mediastinal veins and serves as a marker of injury severity and is commonly associated with aortic dissection.

Rightward displacement of the esophagus or nasogastric tube.

Anterior displacement of the trachea and mainstem bronchi on lateral view.

The false lumen may dissect arteriosclerotic mural calcification equal to or greater than 5 mm away from the aortic wall; although rare, this finding is relatively specific, and should be sought regardless of the modality employed.

Either aneurysm or dissection may cause a left pleural effusion or apical pleural cap due to hemothorax.

Although these findings lack specificity, when more than one of them is present, further evaluation is almost always indicated. An aneurysm that is proximal to the descending aorta should alert the radiologist to consider nonarteriosclerotic etiologies, such as syphilis.

Indications.

When adequate CT is performed, sensitivity for aortic aneurysm is approximately 100%, and specificity approaches 100%. Sensitivity and specificity for dissection are 90-100%. Multislice techniques have improved image quality and diagnostic accuracy compared to previous CT technology.