TIPS: Randomized Trials and Basic Research

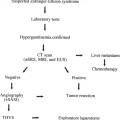

For most interventional radiologists, the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has become a standard tool for mitigating the complications of portal hypertension. With TIPS, a skilled interventionalist can create the equivalent of a surgical small-caliber portocaval shunt by using a purely endovascular, minimally invasive, nonoperative approach; in the hands of an experienced person, the procedure often requires 1 hour to complete. It is a safe and effective method of reducing portal pressure, is excellent for stopping acute variceal bleeding, and, in an increasing number of cases, is proving useful for treating severe ascites and select cases of Budd-Chiari syndrome and hepatorenal syndrome.

In examining the present and future state of TIPS, it is worth reflecting on the remarkable evolution of the procedure. In 1969, Rösch et al1 described creating a percutaneous portosystemic shunt in dogs. Twenty years elapsed before Richter et al reported the first use of stented TIPS in humans.2 Creating the shunt required the better part of a workday, a Dormia basket, Palmaz stents, and a combined transjugular and transhepatic approach. Since then, tens of thousands of TIPS have been created worldwide. One industry-sponsored marketing study projected a worldwide increase in TIPSrelated procedures from approximately 18,000 in 1996 to 50,000 in 1999 (personal communication, Medical Data International). These optimistic figures are based in part on the dissemination of the TIPS technique, growing familiarity among referring physicians, increasing indications for placement (e.g., severe ascites), and, perhaps, increasing prevalence of patients with hepatitis C-related liver disease. The TIPS technique has undergone many technical refinements, and hundreds of scientific articles have been published about the subject.

Despite these facts, several important questions remain unanswered. First, when should TIPS be used rather than other available therapies? Second, how will the problem of the unpredictable durability of TIPS be solved? The latter question is coupled closely with the first, as improved shunt patency could dramatically affect the results of comparative trials by further reducing rates of recurrent symptoms associated with shunt malfunction and the costs of shunt revision.

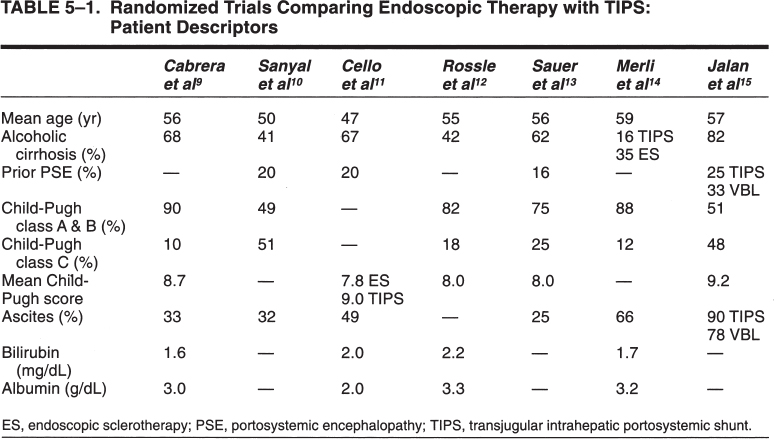

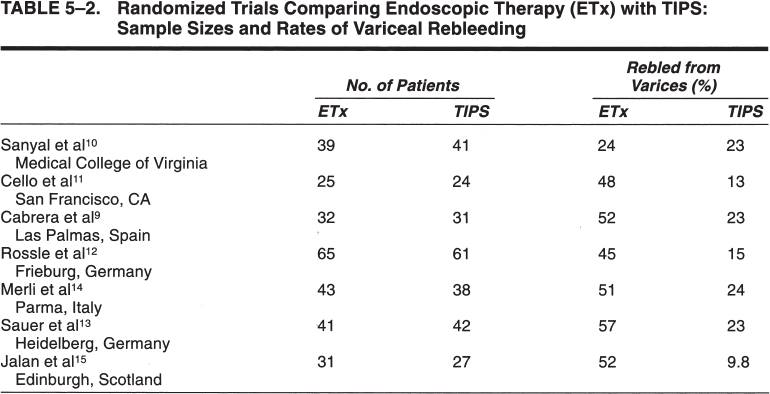

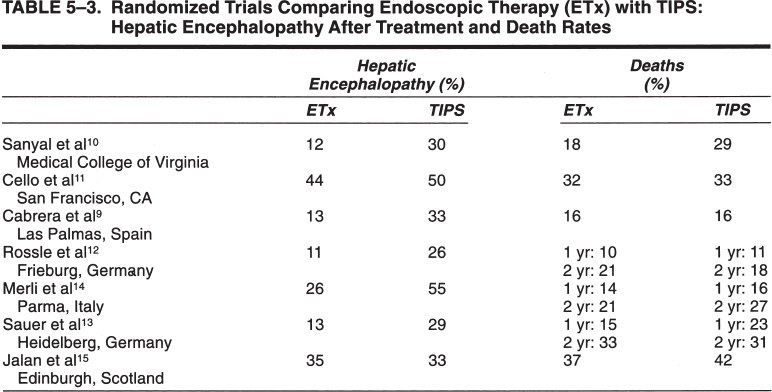

The results of a several randomized trials comparing TIPS with endoscopic therapies have been published in full form and are analyzed in this chapter. Their results are summarized in Tables 5–1, 5–2, and 5–3. In contrast, the literature describing the use of TIPS for treatment of severe or refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome is relatively immature. Several physiologic studies, small patient series, and three uncontrolled 50-patient trials (two retrospective, one prospective) have been published.3–8 As ascites patients typically manifest far more advanced liver disease, portosystemic diversion of nutrient portal flow is less tolerated and significantly higher rates of encephalopathy and hepatic decompensation occur. At present, no randomized trials comparing TIPS with paracentesis have been published, though such multicenter trials are well under way.

Randomized Trials: TIPS and Other Treatments

Randomized Trials: TIPS and Other Treatments

TIPS Versus Endoscopic Therapies

Study 1

Cabrera and colleagues9 randomly assigned 32 consecutive patients with esophageal variceal hemorrhage to endoscopic sclerotherapy (ES) and 31 patients to TIPS placement. The prevalence of alcoholism was 72% in the ES group and 65% in the TIPS group; most patients were men. The patients were relatively well matched for the number of prior episodes of variceal bleeding (10 each), Child-Pugh score (ES group, 7.22; TIPS group, 7.1), mean total bilirubin level (ES group, 1.6 mg/dL; TIPS group, 1.8 mg/dL), and mean units of blood transfused during the index bleed (3.87 U). Unlike most American TIPS series, the population was skewed toward patients with relatively good liver function. For ES patients, the distribution of Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 44%; class B, 50%; and class C, 6%. For TIPS patients, the distribution of Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 45%; class B, 42%; and class C, 13%. The patients were randomized within 3 days of bleeding, and the mean duration of follow-up was 15 months.

The most dramatic finding of the study was the comparatively beneficial effect of TIPS on all aspects of variceal rebleeding. The absolute number of bleeding episodes, the number of patients rebleeding, and the number of units transfused during rebleeding were lower in the TIPS group. Twenty-three percent of TIPS patients rebled compared with 51.6% of ES patients. Serial ES eliminated varices in 20 of the 31 (64%) patients; however, varices reappeared in 11 of the 20 (55%) patients. Notably, 12 of the 16 (75%) ES patients who rebled did so before variceal obliteration. This last point emphasizes one of the risks of variceal sclerotherapy compared with TIPS: the need for weeks or months of endoscopic obliteration sessions. This requirement exposes the patient to a much longer period of risk for variceal rebleeding.

Five patients rebled from ES ulcers, and three died of complications of recurrent bleeding. In the TIPS group, recurrent portal hypertension accounted for the rebleeding in six of seven patients. No TIPS-related procedural deaths and no deaths related to rebleeding after TIPS creation occurred. Not surprisingly, the rate of portosystemic encephalopathy was much lower in the ES group (13%) than in the TIPS group (33%).

One important finding was the lack of a survival difference between the two groups. The cause of death in the ES group included variceal bleeding (n = 3), aspiration (n = 1), sepsis (n = 1), and iatrogenic hernothorax (n = 1). In the TIPS group, patients died of sepsis (n = 1), hepatoma (n = 1), stroke (n = 1), and pulmonary edema (n = 1). To some degree, it is arguable that the TIPS-related deaths better reflect the nonvariceal morbidity of long-standing liver disease rather than the success or complications of a particular method of preventing variceal bleeding.

Study 2

Sanyal and colleagues10 randomly assigned 39 patients to ES and 41 to TIPS creation approximately 10 days after an acute episode of variceal bleeding. The patients were mostly men with either alcoholic (37%) or hepatitis C (39%) cirrhosis. In the ES patients, the severity of liver disease, according to Child-Pugh disease classification, was as follows: class A, 17%; class B, 32%; and class C, 51%. In the TIPS patients, the distribution of Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 15%; class B, 38%; and class C, 46%. Child-Pugh scores and laboratory data were not described. Patients with portal vein thrombosis, hepatoma, and florid alcoholic hepatitis were excluded. Prior encephalopathy was present in 22% of ES patients and in 18% of TIPS patients. In the ES patients, varices were obliterated in 88% of cases and recurred in 28% (unlike those in the study by Cabrera et al9). The authors stressed the particular efficiency of their intensive ES regimen. The median follow-up was almost 1000 days (32 months) in each group.

The rate of rebleeding was essentially equal in both ES and TIPS groups (24% versus 23%, respectively). Ten TIPS and nine ES patients had at least one variceal rebleeding episode. The severity of bleeding and the transfusion requirements were similar. Seven patients bled because of shunt thrombosis or stenosis. Eight ES patients rebled from varices (gastric varices in five patients and esophageal varices in three).

Significantly more deaths occurred in the TIPS group (p < 0.02; 12 versus 7 in the ES group), with median survival durations of 260 days [confidence interval (CI) = 118, 630 days] for TIPS patients and 1,004 days (CI = 740, 1,173 days) for ES patients (note the large CI). Five deaths in the TIPS group were due to rebleeding compared with three in the ES group. New-onset or acutely worsening encephalopathy developed in 30% of TIPS patients and in 12% of ES patients.

Study 3

Cello and colleagues11 randomly assigned 25 patients to ES and 24 to TIPS within 24 hours of an index esophageal variceal hemorrhage. During the 4-year study period, 250 patients were excluded, most of them because they had factors generally accepted as markers for poor survival (e.g., pH, 7.2; prothrombin time 5 seconds greater than control despite transfusion; suspected myocardial infarction). ES was performed every 2 to 7 days during the initial hospitalization and then weekly thereafter. TIPS were created within 48 hours of randomization. Two-thirds of patients in each group were active alcoholics. The patients in the TIPS group had worse Child-Pugh scores at entry than did those in the ES group (9.0 vs. 7.8, respectively). The mean number of units of blood transfused before randomization was also higher in the TIPS group than in the ES group (5.3 vs. 4.0 U). The patients were otherwise statistically well matched. The mean duration of follow-up was similar: 567 days for the ES group and 574 days for the TIPS groups. Varices were initially obliterated, decompressed, or both in 44% of ES patients and in 94% of TIPS patients; one TIPS patient crossed over to the ES group. The prevalence of portosystemic encephalopathy was considered similar for both groups, although grading according to severity was not described.

The overall prevalence of variceal rebleeding was much lower in the TIPS group (12% versus 48%), as was the mean number of episodes per patient (0.17 versus 0.88). The duration of hospitalization during these episodes and the amounts of blood transfused were similar. This study is particularly interesting because it included only patients who had no episodes of variceal bleeding prior to entry into the trial, theoretically addressing a large potential initial selection bias.

Remarkably, there was no statistically significant difference between the number of episodes of new or worsened posttreatment encephalopathy in either group: 44% (11 of 25) for ES patients and 50% (12 of 24) for TIPS patients. On the other hand, the mean duration of hospitalization for portosystemic encephalopathy per patient was higher in the TIPS group than in the ES group (3.7 and 1.2 days, respectively). Again, graded assessment of the encephalopathy was not provided. The authors speculated that the high prevalence of severe liver disease in the study might have obscured differences in encephalopathy that might be evident in a healthier cohort.

Total health care costs and health care costs per day of survival were statistically similar. Finally, survival seemed to improve with TIPS creation, but statistical significance was not achieved.

Study 4

Rossle and colleagues12 randomly assigned 61 patients to TIPS creation and 65 to endoscopic therapy (ET) for the treatment of gastric and esophageal variceal bleeding. Sixty-four patients were excluded (42 refusals, 22 exclusions). Alcoholic liver disease was present in 69% of TIPS patients and in 65% of the ET patients. The breakdown of TIPS patients according to Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 28%; class B, 54%; and class C, 18%. For ET patients, the breakdown was as follows: class A, 34%; class B, 48%; and class C, 18%. Approximately 40% of patients in each group were randomized after their first episode of bleeding (similar to the patients in the study by Cello et al3). All episodes of acute bleeding were initially controlled with ET. The mean time between the index bleed and randomization was 6.3 days for the TIPS group and 4.4 days for the ET group. Variceal embolization was performed in half of the TIPS patients by using bucrylate, Lipiodol, or both. All TIPS patients received anticoagulation therapy.

ET differed from ET performed in the preceding studies. Treatments included sclerotherapy (polidocanol) or band ligation at 2- to 5-day intervals until variceal eradication or at least six treatments occurred. It appears that these investigators may have attempted more intense and rapid early obliteration of varices than other investigative groups. Gastric varices also were treated endoscopically by using intravariceal injection of iodized oil-bucrylate solutions. Sclerotherapy alone was used in about half of the ET patients; the other half underwent sclerotherapy and band ligation. In addition, 68% of ET patients received propranolol, which was titrated to reduce the heart rate by 25%. The mean duration of follow-up was similar: 14 months compared with 13 months for TIPS and ET groups, respectively.

Variceal rebleeding was much lower in the patients with shunts: 15% of TIPS patients (n = 9) had 11 episodes of rebleeding, whereas 45% (n = 29) of ET patients had 56 episodes of rebleeding. Other causes of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in the groups included Mallory-Weiss tears, sclerotherapy ulcers, portal gastropathy, and peptic ulcers; however, these causes accounted for only eight additional upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding episodes in the TIPS group and 44 additional episodes in the ET group (100 total episodes, including variceal rebleeding). The time to any form of rebleeding was significantly different between groups. The 1-year variceal rebleeding rates for TIPS and ET groups, respectively, were 15% and 41% for variceal rebleeding and 23% and 55% for all causes. Follow-up transfusion requirements also were significantly lower in the TIPS group than in the ET group: 20% of TIPS patients required 96 units of packed red blood cells, and 38% of ET patients required 272 units.

Survival was similar in both groups. Estimated 1-year rates for TIPS and ET groups, respectively, were 90% and 89%, and 2-year rates were 79% and 82%. The probability of developing hepatic encephalopathy was significantly higher in the TIPS group. Encephalopathy was seen in 36% of TIPS patients and in 18% of ET patients. Clinically significant encephalopathy (more than one 3-month episode of grade 2 encephalopathy or chronic encephalopathy of at least grade 1) occurred in 26% of TIPS and in 11% of ET patients. Refractory encephalopathy occurred in four patients, two of whom crossed over into the TIPS group after ET failure (all patients responded to placement of flow-reducing TIPS).

Finally, one compelling quality-of-life measure of the two therapies to be evaluated was the number of repeated interventions. The TIPS group required 24 shunt revisions, whereas the ET group required 331 endoscopic interventions.

Study 5

Sauer and colleagues13 randomized 42 patients to TIPS creation and 41 patients to ES plus propranolol within 1 to 3 days of an endoscopically controlled episode of esophageal variceal bleeding. As in the study by Cello et al,3 patients were excluded if they had undergone prior treatments for varices, which removed a potentially important prior treatment bias. Exclusion criteria included prior endoscopic or surgical treatment of varices, gastric varices, or persistent bleeding 24 hours after admission. The sample sizes and power analyses were based on the assumption that 50% of ES patients would rebleed (compared with 20% of TIPS patients). TIPS placement and ES were performed within 2 days of randomization. ES was performed weekly for 1 month and continued to 3 months thereafter until the varices were obliterated. ES and TIPS groups were restudied endoscopically and venographically, respectively, at 3-month intervals. The clinical characteristics, severity of bleeding, and time to treatment of the two groups were deemed comparable. Alcoholic liver disease was present in 61% of TIPS and 63% of ES patients. The breakdown of TIPS patients according to Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 35%; class B, 43%; and class C, 21%. For ES patients, the breakdown was as follows: class A, 29%; class B, 44%; and class C, 27%. The mean Child-Pugh scores for the TIPS and ES groups were 7.76 and 8.26, respectively. The mean duration of follow-up was 1.6 years for TIPS patients and 1.45 years for ES patients.

Varices were obliterated in 74% of the ES patients after a median time of 7.4 months and mean time of 11.5 months. The cumulative rate of reappearance of varices after ES was 32% at a mean of 12 months after obliteration. The cumulative rate of variceal rebleeding was 23% for TIPS patients (six episodes, four shunt occlusions, and two stenoses) and 57% for ES patients (33 episodes). More than half of the ES patients developed at least one rebleeding episode. When rebleeding from sclerotherapy ulcers was included, the ES rebleeding rate rose to 71% at 2-year follow-up. Uncontrolled recurrent bleeding was observed in the ES group but not in the TIPS group. The only significant predictor of higher rebleeding risk was the ES treatment group (p = 0.002); the Child-Pugh score was marginally predictive (p = 0.054).

The frequency of hepatic encephalopathy was significantly higher in the TIPS group (29% versus 13%). Hepatic encephalopathy was positively correlated with higher Child-Pugh scores, TIPS treatment group, and preexisting hepatic encephalopathy. Overall mean survival times were similar for both groups (TIPS group, 27.5 months; ES group, 29 months) but were strongly correlated with the Child-Pugh score, which reflects a finding seen in nearly all of the randomized trials of patients with variceal bleeding: Long-term survival is correlated with residual liver function.

Study 6

Merli and associates14 randomly assigned 38 patients with esophageal variceal bleeding to TIPS creation and 43 patients to ES. At each participating center, patients were divided into three strata and randomized from within those groups, as follows: stratum I, bleeding within 1 week of randomization; stratum II, bleeding within 1 to 6 weeks; stratum III, bleeding within 6 weeks to 6 months. Acutely bleeding patients were randomized into treatment groups no sooner than 24 hours after the acute bleeding was controlled with other methods and the patients were hemodynamically stable. The samplesize assumptions were similar to those used by Sauer et al,7 although no accommodation was made for the resultant small sizes of patient groups within each treatment group stratum. This reflects a potentially important study selection bias unique to this trial: the assumption that outcome will be similar among the different strata of each treatment group, allowing the authors to bundle them together into a single sample size calculated in one power analysis. This assumption may be unsupported because the heterogeneity of the individual patient strata.

In contrast to other studies, there was a higher prevalence of viral hepatitis. Cirrhosis was attributed to viral disease in 71% of TIPS patients and 44% of ES patients and to alcohol abuse in 16% of TIPS patients and 35% of ES patients. The patients were generally healthier than those in the U.S. studies. The breakdown of TIPS patients according to Child-Pugh disease was as follows: class A, 34%; class B, 53%; and class C, 13%. In ES patients, the breakdown was as follows: class A, 30%; class B, 58%; and class C, 12%. Unlike the criteria in several other studies, patients were not excluded from the study if prior variceal bleeding had occurred (38% of patients enrolled had previous bleeds). ES sessions were performed at 7- to 10-day intervals until varices were eradicated. The mean follow-up was 75 weeks. Endoscopic and shunt imaging took place at 6-month intervals. Treatment was administered within 3 days of bleeding in stratum I patients, within 20 days in stratum II patients, and within 64 days in stratum III patients. Varices were successfully eradicated with ES in 51% of patients. TIPS could not be created in three patients because of stent migration or inability to place the stent. Both the total number of rebleeds and the number of first rebleeds were smaller in the TIPS group. Rebleeding occurred in 51% of patients in the ES group and in 24% of patients in the TIPS group. The cumulative 1- and 2-year probabilities of remaining free of bleeding in the TIPS and ES groups were, respectively, 79% and 69% (TIPS) and 48% and 40% (ES). Forty-one episodes of rebleeding occurred in the ES group, and 12 occurred in the TIPS group. The cumulative probability of remaining free of rebleeding was significantly higher in the TIPS patients in stratum I; the difference between treatment groups was not statistically significant in the strata II and III groups.

The overall mortality was 21% and was split evenly between the groups. The 1- and 2-year actuarial probability of survival was statistically similar in both groups (TIPS, 84% and 73%; ES, 86% and 79%, respectively). Hepatic encephalopathy developed in 26% of the ES patients and in 55% of the TIPS patients. Eight episodes of hepatic encephalopathy were grade III to IV in the TIPS group, compared with three in the ES group. Prognostic factors for hepatic encephalopathy or stratification according to strata or Child-Pugh class were not described. TIPS malfunction occurred in 66% of patients, recurring in half of these patients. Angioplasty alone was used to revise the TIPS in 73% of cases. The cumulative rate of TIPS malfunction was 61% at 1 year.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree