54 Transversus Abdominis Plane Block

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks can provide pain relief following surgeries that involve a lower abdominal incision. Examples include the Pfannenstiel (transverse) incision for cesarean delivery or hysterectomy, and surgeries that use a lower midline incision. Although somatic nerves of the abdominal wall are anesthetized, visceral pain following surgery is still an issue. These blocks therefore do not always provide definitive pain relief and multimodal analgesia is often necessary. TAP block reduces patient-controlled anesthesia (PCA) morphine requirements following surgery but does not appear to reduce opioid-related side effects.1 Another application for TAP blocks has been pain relief for anterior iliac crest bone grafts. TAP blocks also can be used as part of the diagnostic workup of chronic abdominal pain to distinguish visceral and somatic components as potential causes. Many variations of the TAP block exist, but most use a posterior or slightly modified approach.

Sonographic Landmarks

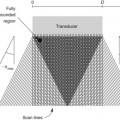

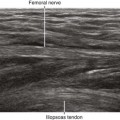

The first step in performing TAP blocks with ultrasound guidance is to identify the muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall (Table 54-1). The external oblique is usually the most echogenic muscle of the anterolateral abdominal wall. The external oblique and internal oblique muscles typically extend farther posteriorly than the transversus abdominis muscle. Retroperitoneal fat (hypoechoic appearance on ultrasound scans) lies under the posterior aspect of the transversus abdominis muscle. The layers underneath the transversus abdominis muscle are (in order) the transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and peritoneum. The quadratus lumborum muscle is hypoechoic and therefore difficult to visualize on ultrasound scans (as is the retroperitoneal fat).

Table 54-1 Ultrasound Anatomy of the Anterolateral Abdominal Wall and Related Structures

| Structure | Sonography | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous tissue | One or two layers | |

| External oblique | Often hyperechoic | |

| Internal oblique | Thickest muscle | Rankin et al |

| Transversus abdominis | Thinnest muscle | Rankin et al |

| Hypoechoic | Hebbard et al | |

| Retroperitoneal fat | Fibro-fatty echoes | Gore et al |

| Quadratus lumborum | Hypoechoic | Callen et al |

| Peritoneum | Very hyperechoic | Hanbidge et al |

| Comet-tail artifact | Thickman et al | |

| Gut sliding |

Rankin G, Stokes M, Newham DJ. Abdominal muscle size and symmetry in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve 2006;34:320–6; Hebbard PD, Barrington MJ, Vasey C. Ultrasound-guided continuous oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane blockade: description of anatomy and clinical technique. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010;35(5):436–41; Gore RM, Callen PW, Filly RA. Displaced retroperitoneal fat: sonographic guide to right upper quadrant mass localization. Radiology 1982;142(3):701–5; Callen PW, Filly RA, Marks WM. The quadratus lumborum muscle: a possible source of confusion in sonographic evaluation of the retroperitoneum. J Clin Ultrasound 1979;7(5):349–52; Hanbidge AE, Lynch D, Wilson SR. US of the peritoneum. Radiographics 2003;23:663–84; Thickman DI, Ziskin MC, Goldenberg NJ, et al. Clinical manifestations of the comet tail artifact. J Ultrasound Med 1983;2:225–30.

The nerves of the abdominal wall are most visible where they enter the TAP. In this location they are relatively large and shallow with the surrounding muscles providing contrast. The T11 and T12 (subcostal) nerves are often accompanied by intercostal arteries and can often be identified as they run within the TAP. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves cross over the anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum muscle2 but are difficult to visualize in this anatomic location.