Fig. 41.1

Small fistula in the lower trachea. Whitish purulent material from the cancer occluded esophagus is seen extruding into the airways

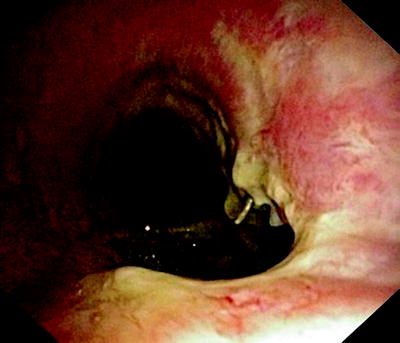

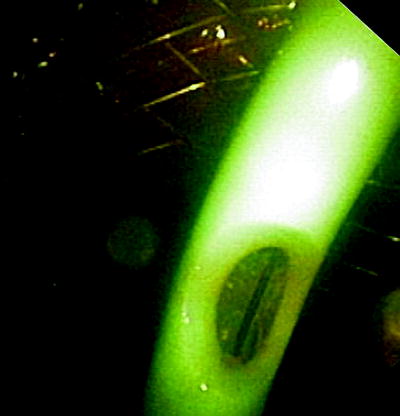

Fig. 41.2

Large fistula with necrotic edges and lymphangiosis of the tracheal mucosa

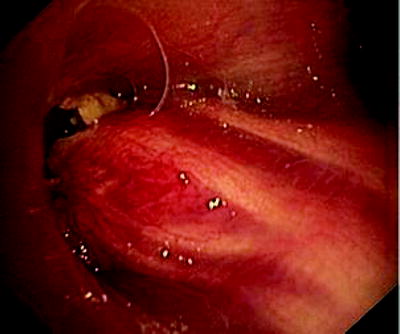

Fig. 41.3

Huge fistula after radiation therapy of a tracheal cancer. The partially necrotic esophagus can be seen through the posterior membrane of the trachea

Fig. 41.4

Esophageal tumor compressing the left stem bronchus. The fistula opening becomes only visible if the narrowing is passed with a rigid bronchoscope

Fig. 41.5

Esophageal cancer, invading through the tracheal wall. Three communications have developed into the respiratory tract. Patient who had been dysphagic for weeks became almost asphyctic

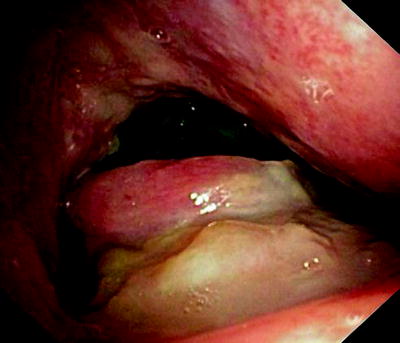

Fig. 41.6

Esophagoscopic view of a “clean” fistula following resection and radiation therapy of an esophageal cancer

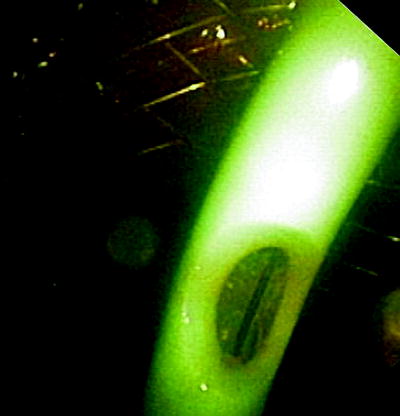

Fig. 41.7

Esophagoscopic view on an esophageal tumor (right) and a covered tracheal stent that had been placed in order to prevent aspiration

Fig. 41.8

Malignant tumor, obstructing the esophagus. The fistula is located behind the tumor and can only be seen from the bronchial side

Fig. 41.9

Completely malignant destruction of the esophagus. Fistula into the stem bronchus is located distally to the necrotic cavity in the mediastinum

In Fig. 41.3, the already partially necrotic esophagus starts to protrude into the lumen of the trachea. As long as no prosthesis is placed into the esophagus, breathing is not impaired. However, the necrotic edges of the tracheal fistula indicate that there will be rapid deterioration, and immediate palliation is required. Figures 41.4 and 41.5 illustrate the effect of a growing esophageal cancer on the airways. A stem bronchus or the whole carinal region can be compressed. The symptoms are intractable cough, stridor, and dyspnea.

Figure 41.6 shows a fistula with clean edges, indicating that there is no cancer, while Fig. 41.7 was made in a patient with growing esophageal cancer and a 2-cm-long fistula. A self-expanding metal stent that had been deployed into the trachea is seen from the esophagus. In all these cases, saliva and food spill over into the airways when the patient swallows, and acidic gastric content gets into the lungs.

Figures 41.8 and 41.9 show cases where only fluid either from the oral side or from the stomach gets into the respiratory tract. The cancer-affected esophagus is completely obstructed. The clinical symptoms depend on whether the fistula has developed proximally or distally of the occlusion. In any case, nutrition via the normal route has become impossible, and aspiration pneumonitis has to be expected.

Treatment

When the diagnosis has been made, the immediate goal is preventing soilage into the lung. Patency of the airways has to be preserved or restored; swallowing of at least saliva, preferably with fluid and food, should be enabled. The therapeutic approach depends on the clinical condition, the type, size, and location of the fistula.

Benign Fistulas

Benign fistulas should be operated if the clinical condition permits. The patient should not be septic and should not require ventilator support. The surgical access with Kocher’s incision, sternotomy, or posterolateral incision depends on the height of the fistula. After preparation, the fistula is dissected from the esophageal side first, followed by sleeve resection of the trachea. A muscle flap (e.g., from the m. sternohyoideus) is often used to protect the anastomoses. There are two accepted exceptions from this approach. If a fistula is very small, an attempt can be made to glue the fistula with fibrin. We have been successful in a two cases using the Vivostat® system with autologous fibrin as illustrated in Fig. 41.10.

Fig. 41.10

Small fistula (sequela from radiation therapy) has been sealed with autologous fibrin

At the other end of the spectrum are patients who are too sick for immediate surgery. Poly-trauma patients or those with complete ruptures of trachea and or esophagus should not be primarily operated. The first priority is to stabilize the clinical situation. Tube and stent placements can be used as bridging methods.

The worst scenarios are encountered if a patient with respiratory failure requires positive pressure ventilation and the walls of trachea and esophagus are eroded, e.g., by a tube cuff. The ventilator pumps air into the abdomen, further deteriorating the respiratory condition by lowering residual lung volume promoting gastric reflux into the lungs. The standard approach is by placing the cuffed tube further down into the trachea. Sometimes a double lumen tube has to be placed into a stem bronchus in order to maintain gas exchange. The drawback is that bronchial toilette with suctioning through such a tube is heavily impaired because of the small lumina. Another emergency approach that has been recommended is blocking the fistula from the esophageal side with a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube. I have personally used a dilatation balloon for that purpose. The third alternative would be the use of extracorporeal lung support devices. After the patient has been stabilized, stents can be placed.

Malignant Fistulas

Malignant fistulas can result from direct erosion of cancer into the anatomical structures or as a result of treatment. Quite often, we see patients with esophageal cancer who have received postoperative chemoradiotherapy, suddenly presenting with symptoms of fistula. This could be due to cancer recurrence, progression of disease, or late sequelae of treatment with local dehiscence. There are additive side effects of mediastinal radiotherapy if bevacizumab is administered as part of the treatment. Once a fistula has developed in a cancer patient, his overall clinical condition declines rapidly. Most of these patients suffer already from general weakness, cachexia, dyspnea, and pain. The continuous aspiration and coughing is exhausting and creates a constant fear of eating and drinking with the consequences of further loss of weight. Inadequate clearance of purulent secretions and aspiration pneumonitis result in respiratory failure even if the tracheal lumen is not compromised. With supportive care without palliative measures, patients have a mean survival expectancy between 1 and 6 weeks. Placement of stents is considered the treatment of choice for patients suffering from these malignant fistulas.

Stent Placement

State-of-the-art stents are self-expanding structures that can be placed endoscopically. In the above-mentioned situations, we have the choice of placing such prosthesis into either the esophagus, the trachea, or into both organs (double stenting). Before discussing the techniques, I would like to elaborate on some biomechanical aspects first. Regardless of where they are placed, stents can fulfill two purposes. They can establish patency of a lumen, and they can seal a hole. Though this seems simple and obvious, there is an imminent problem. In order to open a compressed or strictured lumen, a stent has to expand inside this tubular structure by applying a certain pressure (hoop stress). Once deployed, stents are held in place by friction due to contact pressure. Mild oversizing prevents stent migration. However, if a lumen is stretched, the hole in this lumen is also stretched, resulting in enlargement of the fistula. In other words, whether a stent is placed into the esophagus or into the trachea, chances that a fistula will heal are minimized as its edges are torn apart. Therefore, stent therapy is a palliative measure that can save a patient’s life and hopefully improve his quality of life, but we cannot expect it to promote healing of a fistula.

If the decision has been made to place a stent, the next questions have to answer whether single or double stenting should be performed, in which order, and by whom. The later question should not influence decision making. However, real-life conditions in most hospitals do certainly have an impact. If we get patients from outside with a single stent coming from a gastroenterologist, they have a stent in the esophagus as well as a PEG. If a patient with similar clinical problems and histories had been admitted to a pulmonologist first, they usually come with a tracheal stent and a nasogastric tube. While overall more than two thirds of fistulas result from esophageal cancers, in the prospective study from Herth, 74% of the patients had bronchogenic carcinomas, and 26% had primary esophageal tumors. Ideally, patients should have access to all methods. Fortunately, we do all procedures in our department with full support from thoracic surgeons and critical care colleagues.

Placing an esophageal stent has certain advantages. Esophageal stents are round shaped like the target organ. In contrast to airway stents, these prostheses can be deployed without the risk of suffocation as the devices do not open and expand immediately. The dimensions are usually bigger. In former times, we had to insert rigid Celestine tubes, sometimes with huge cuffs which required very deep sedation or general anesthesia. At present, for most cases, self-expanding metal stents are used. They are available from several companies, in different lengths and diameters. They are inserted over a guide wire as illustrated in Fig. 41.11.

Fig. 41.11

A covered self-expanding esophageal stent is placed under direct endoscopic vision. If the stenosis is too tight, the stent can be deployed under fluoroscopical control

Alternatively, self-expanding polymer stents (Fig. 41.12) can be used.

Fig. 41.12

The self-expanding Polyflex esophageal stent is an alternative to covered metallic stents

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree