Figure 8.1

Surgical levels of the neck

Level I constitutes lymph nodes above the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle cephalad to the hyoid bone and inferior to the inferior border of the mandible and includes the submental group of nodes. For Levels II–IV , the posterior border is the posterior edge of the sternomastoid muscle, and the anterior border is the laryngeal complex. Level II (upper jugular region) extends from the skull base and spinal accessory nerve superiorly to the hyoid bone inferiorly and is subdivided into IIA below the spinal accessory nerve and IIB above the spinal accessory nerve. Level III (mid-jugular region) extends from the hyoid superiorly to the cricoid cartilage inferiorly. Level IV (lower jugular region) extends from the cricoid cartilage down to the clavicle. Level V is a triangular region bounded anteriorly by the posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and posteriorly by the anterior edge of the trapezius muscle. It is subdivided into the region 5A above the level of the cricoid cartilage and 5B (supraclavicular region) below the level of the cricoid cartilage. Level VI (central compartment) is composed of four subcompartments: (1) prelaryngeal (Delphian nodal group), (2) pretracheal, (3) left paratracheal, and (4) right paratracheal. It extends from the hyoid bone superiorly to the clavicle. A Level VII or superior mediastinal group has also been described which appears to be encompassed in the lower part of the central neck dissection group described by ATA [2]. Typically standard neck dissection for papillary carcinoma of the thyroid excludes Levels I, IIB, and V due to the low prevalence of disease in these subareas. An exception to this is a patient with bulky lateral neck nodal disease where these areas may require dissection. In addition to the lymph node levels described above, many classification systems pertaining to the cervical lymph nodes have been published, including Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) classification, American Head and Neck Society (AHNS) classification, Japanese classification and the compartment classification (German classification) [3–6]. Cunnane et al. recently published a thyroid-specific, multidisciplinary, clinically validated nodal classification system that divides the neck into multiple stand-alone surgically distinct, side-specific compartments [7]. Distribution of nodal disease likely varies between primary presentation and recurrent disease. A recent study that mapped nodal distribution in PTC reported that at the first presentation, nodal disease is concentrated in the central neck, while in recurrent disease, this pattern is reversed with the nodes b eing more focused in the lateral neck [8] (Fig. 8.2). The same study reported that with recurrent nodal disease, ectopic nodal location outside of the typical central and lateral neck regions (retropharyngeal, sublingual region, subcutaneous location, axilla, and chest wall) occurred in almost 10% of patients, suggesting that axial imaging should be performed in patients with recurrent nodal disease [8].

Figure 8.2

Thyroid cancer radiographic map . Outer boxes (A, B) indicate the lateral neck nodal compartments, whereas the inner boxes (C, D, L, T) indicate the central neck nodal compartments. Box labeled (E) represents ectopic nodal groups

Nodal subgroups can be further classified into the lateral (Levels II–V) or central (Levels VI ± VII) neck which correlates with the current prevailing philosophy of a “compartment-oriented dissection” in surgical management of nodal disease. Lateral neck dissection for thyroid carcinoma generally encompasses Levels II, III, and IV, and central neck dissection encompasses prelaryngeal, pretracheal, and at least one paratracheal r egion (Fig. 8.3). Note that, occasionally, especially in patients with aggressive subtypes of thyroid cancer, patients may present with nodal metastases which are outside of these known neck regions. However, the vast majority of patients with well-differentiated nodal metastasis can be described with this terminology.

Figure 8.3

“Compartment-orie nted dissection.” Lateral neck dissection is divided into upper (Level II lymph nodes), middle (Level III lymph nodes), and lower (Level IV lymph nodes). Central neck dissection encompasses the pretracheal region, the prelaryngeal region, and at least one paratracheal region

Ultrasound Features of Benign vs. Malignant Lymph Nodes

The normal neck contains approximately 300 ly mph nodes. Benign nodes are typically flattened or slightly oval in shape, and most are less than 0.5 cm in size in their short axis. They may enlarge for various reasons including infection, inflammation, allergy, and malignancy. Those in Levels I and II commonly enlarge during upper respiratory infections or inflammation. Therefore, the overall size of a lymph node is of little benefit in determining if a lymph node is malignant or benign, and ultrasound criteria other than size must be used to differentiate benign hyperplastic lymph nodes from those that are malignant. While larger lymph nodes should, and do, attract our attention, additional characteristics such as shape, hilar line, calcifications, cystic degeneration, and vascularity need to be assessed to determine the probability of malignancy.

Unlike thyroid nodules which are measured in true transverse, sagittal, and AP axes, the lymph nodes are measured in long and short axes. The long axis will usually align close to the sagittal plane, but lymph nodes typically orient in an oblique axis. Measurements are made in two planes, initially holding the transducer in the transverse and sagittal planes. The largest diameter of the node is measured and defined as the “long-axis diameter.” Then the largest diameter perpendicular to the first plane is measured and defined as the “short-axis diameter.” The ratio of the long to short axis is then calculated as the long/short ratio [9]. Benign lymph nodes are usually flattened with a long/short ratio > 2. Inflamed or hyperplastic lymph nodes typically appear enlarged but usually maintain the flat shape and a long/short ratio > 2. Malignant lymph nodes usually have a more rounded morphology with a long/short ratio < 2. In an early publication, Steinkamp et al. reported a 95% accuracy in differentiating benign from malignant cervical nodes using a long/short ratio cutoff of 2 [9]. However Leboulleux subsequently found that the long/short ratio (using the same cutoff of 2) had only a 46% sensitivity and 64% specificity [10].

A normal lymph node has a hypoechoic cortex but often shows a central hyperechoic hilum containing fat and intranodal blood vessels referred to as a hilar line. The hilar line is more prominent in older patients. Malignant lymph nodes in the neck, whether they are metastatic from the thyroid or elsewhere (i.e. squamous cell carcinoma), or lymphoma will seldom show a hilar line, thought to be due to interruption of lymphatic flow by tumor invasion. However, specificity of hilar absence for malignancy is reportedly only 29% as the hilum may be difficult to visualize in a benign node [10, 11]. Thus, the presence of a hilar line is reassuring, but its absence is not a highly suspicious finding. When ultrasound is performed on a patient with nodular goiter, or a patient with a history of thyroid cancer, finding a prominent lymph node with a rounded shape (long/short axis ratio < 2) and absent hilar line warrants further evaluation of the node (Figs. 8.4, 8.5, 8.6, 8.7, and 8.8).

Figure 8.4

Benign lymph node. The normal neck contains scores of lymph nodes some of which are easily seen with ultrasound. This lymph node (calipers) appears benign because it is elongated with a long-/short-axis ratio > 2

Figure 8.5

The same lymph node in Figure 8.4 in sagittal view. Despite a maximum dimension of 3 cm, it is clearly benign with long-/short-axis ratio >>2 and a clear central hilum

Figure 8.6

Power Doppler of the previous lymph node shows vascularization of the hilum which contains small arterioles. Note there is no vascularization seen in the periphery of the node

Figure 8.7

Benign lymph node. This lymph node is slightly more rounded with a long-/short-axis ratio < 2 in the transverse view. However it has a central hilum, and vascularity is limited to the hilum. The long to short axis can be seen to be >2 in Fig. 8.8 in the sagittal view

Figure 8.8

Same lymph node in sagittal (longitudinal) view. Long/short axis is >2 and a broad central hilum is present

Several ultrasound findings, when present, are highly suspicious for malignancy in lymph nodes [12] (Table 8.1). Any lymph node calcification, particularly microcalcifications but also amorphous calcifications with posterior acoustic shadowing, raises a strong suspicion of malignancy (sensitivity 46%, specificity 100%) [9]. Cystic necrosis, often recognized because of uneven posterior acoustic enhancement, is another highly specific sign of malignancy (although this also may be seen in tuberculosis of lymph nodes) (Figs. 8.9, 8.10, 8.11, 8.12, 8.13, 8.14, 8.15, 8.16, 8.17, 8.18, 8.19, 8.20, and 8.21).

Table 8.1

Sensitivity and specificity of suspicious lymph node features

Feature | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

Short axis > 0.5 cm | 61 | 96 |

Long axis > 1 cm | 68 | 75 |

Long/short axis < 2 | 46 | 64 |

Hyperechogenic hilum absent | 100 | 29 |

Hypoechogenicity | 39 | 18 |

Hyperechogenic punctuations (calcifications) | 46 | 100 |

Cystic appearance | 11 | 100 |

Chaotic or peripheral vascularity | 86 | 82 |

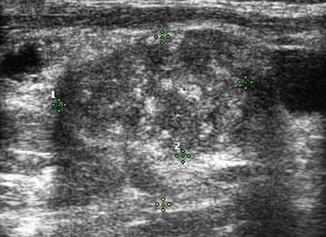

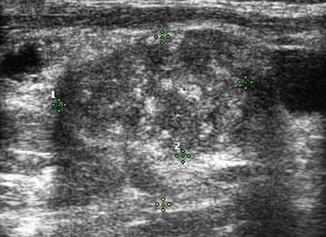

Figure 8.9

This markedly heterogeneous lymph node (calipers) contains scattered calcifications indicating metastatic papillary thyroid cancer

Figure 8.10

This 2.1 cm rounded lymph node in the right neck is >90% cystic; note the distal enhancement. Although occasionally seen in tuberculosis, cyst formation within a lymph node usually indicates metastatic papillary thyroid or oropharyngeal carcinoma

Figure 8.11

This atypical appearing lymph node is heterogeneous and demonstrates multiple areas of cystic necrosis. Cystic degeneration within a lymph node is often first suspected because of uneven distal acoustic enhancement (arrow)

Figure 8.12

This metastatic lymph node, less than 1 cm in size, contains cystic necrosis on the medial side which is hypoechoic (calipers) and shows enhancement. The other side (arrow) is solid and hyperechoic. US-guided FNA of the hypoechoic area yielded negative cytology but high levels of Tg in needle washout—a finding not unusual when cystic necrosis is present

Figure 8.13

This compartment IV lymph node, deep to the SCM, shows multiple features highly suggestive of malignancy including rounded morphology and microcalcifications

Figure 8.14

A central compartment VI paratracheal lymph node with rounded morphology and loss of central hilar line

Figure 8.15

Ultrasound of 54-year-old female 36 years after her thyroidectomy reveals a paratracheal lymph node (arrow) in the right central compartment. Note the long/short axis is <2, and several calcifications are seen indicating malignancy

Figure 8.16

A 1 cm lymph node (1) and a 0.5 cm lymph node (2) in the lateral neck are both rounded without a hilar line. Both nodes had papillary thyroid cancer at surgery

Figure 8.17

Despite a long/short ratio > 2, this 2.5 cm lymph node is clearly abnormal with irregular contour, microcalcifications, and absence of hilar line. Figure 8.23 shows a Doppler image of the same node demonstrating disordered peripheral vascularity

Figure 8.18

This lymph node (calipers) was suspicious because of its borderline long/short axis of 2 and absent hilum. Surgery confirmed metastatic papillary thyroid cancer

Figure 8.19

Metastatic lymph node (calipers) in left central compartment with long/short axis < 1 and no hilar line

Figure 8.20

Right compartment IV lymph node with rounded morphology (long/short > 2), loss of central hilum, and possible microcalcifications. FNA cytology showed papillary thyroid carcinoma

Figure 8.21

Despite a normal long/short axis > 2, this lymph node posterior to the carotid artery is suspicious with central microcalcifications. However, biopsy demonstrated sarcoidosis

Assessment of the pattern of lymph node vascularity using color or power Doppler is instrumental in assessing risk of malignancy in lymph nodes. Power Doppler is preferred over color Doppler for lymph node evaluation, because of its sensitivity to arteriolar blood flow. In order to achieve adequate sensitivity to small amounts of flow, pulse repetition frequency (PRF) should be set to <1000 and a low wall filter should be utilized. Benign nodes generally show vascularization limited to the central hilum, but malignancy disrupts this flow and causes chaotic vascularization throughout the peripheral cortex due to recruitment of vessels into the periphery of the node [13, 14]. The specificity of disordered peripheral vascularity is only 82%, as reactive nodes may also show this feature. However, this feature has been described as having the “best sensitivity specificity compromise” [10], and finding disordered vascularity warrants further evaluation (Figs. 8.22, 8.23, 8.24, 8.25, and 8.26).

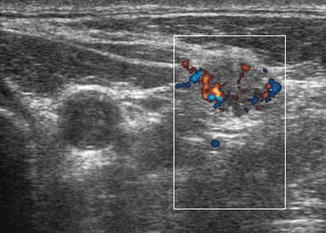

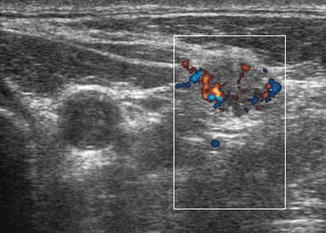

Figure 8.22

Power Doppler of lymph node shows vascularization of the periphery of the node rather than the normal hilar vascular pattern

Figure 8.23

Power Doppler of lymph node (same lymph node as in Fig. 8.17) demonstrating chaotic peripheral vascularity

Figure 8.24

This soft tissue metastasis is located superficial to the SCM muscle. Malignancy was suspected due to the abnormal vascular pattern and confirmed by cytology and TG analysis

Figure 8.25

Power Doppler of lymph node shows a malignant vascular pattern. Tg in needle washout was high confirming malignancy

Figure 8.26

Power Doppler of lymph node shows peripheral vascular pattern of malignancy. FNA cytology was positive, and Tg in the needle washout was >10,000

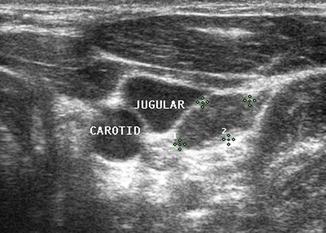

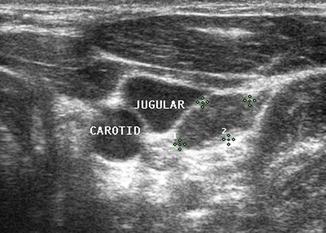

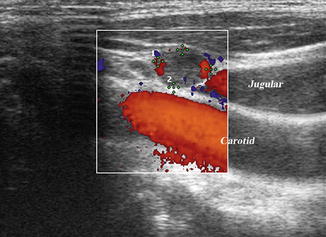

The internal jugular vein lies adjacent to the carotid artery in the neck. Since metastatic nodes commonly occur in proximity to the jugular vein or in the carotid sheath, any deviation of the jugular vein away from the carotid artery strongly suggests the presence of a malignant lymph node. The entire length of the vessels should be surveyed closely with particular attention given to any area where the artery and vein diverge. Moving the ultrasound transducer in several planes may help to reveal an obscure node.

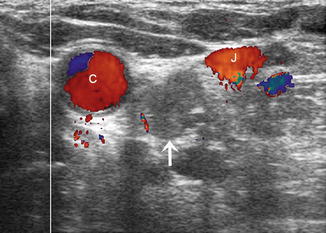

In addition to causing deviation of the internal jugular vein, malignant lymph nodes tend to compress the vein and cause partial obstruction to blood flow. Color or power Doppler may demonstrate the impeded blood flow in the jugular vein. Benign lymph nodes , unless severely enlarged, rarely deviate or obstruct the jugular vein (Figs. 8.27, 8.28, 8.29, 8.30, 8.31, 8.32, and 8.33).

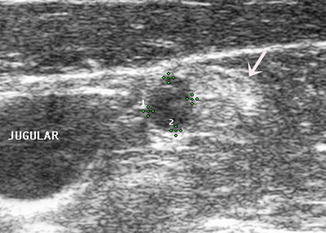

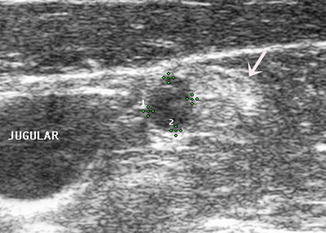

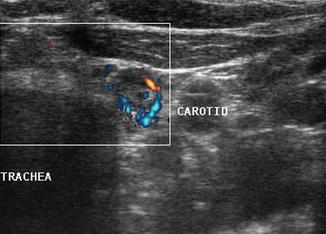

Figure 8.27

On transverse view, this small rounded lymph node (calipers) without a hilar line is in close proximity to the great vessels

Figure 8.28

Same lymph node (calipers) in longitudinal view shows compression of the jugular vein against the carotid. US-guided FNA confirmed malignancy

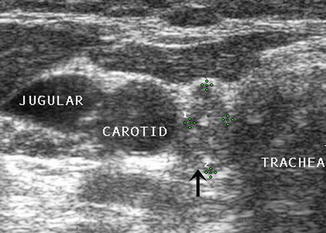

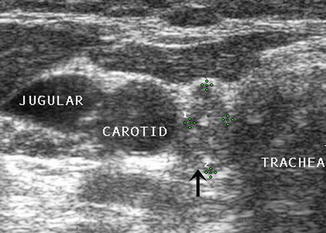

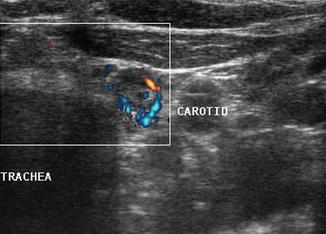

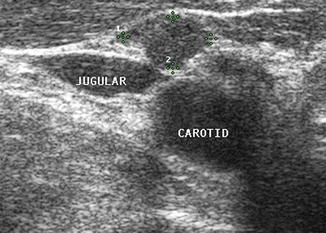

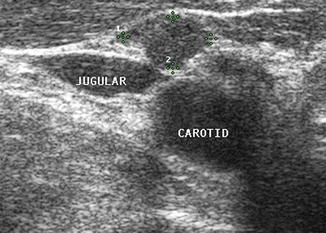

Figure 8.29

This 1.7 cm lymph node (calipers) separates the carotid and jugular. Its location and shape (long-/short-axis ratio < 2) strongly suggested malignancy which was confirmed by US-guided FNA

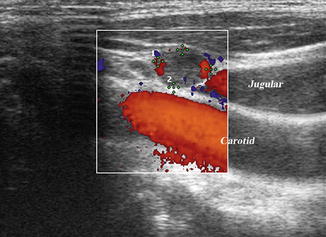

Figure 8.30

This 2.6 cm lymph node is compressing the jugular vein and obstructing its blood flow. It is essential to apply very light pressure with the transducer when assessing whether vascular compression is present

Figure 8.31

This irregular rounded lymph node (arrow) was discovered because of the separation of the jugular from the carotid. The calcification at 3 o’clock strongly suggests malignancy, but US-guided FNA is required before surgery

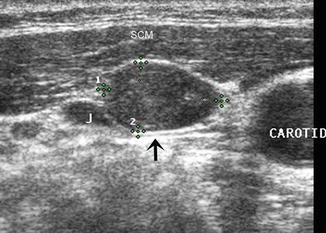

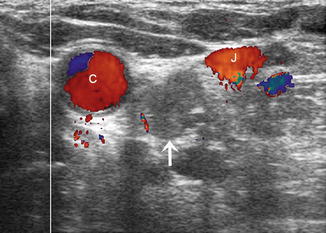

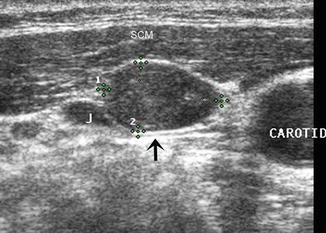

Figure 8.32

Transverse view of a metastatic lymph node (calipers) in the right neck beneath the SCM and lateral to the carotid artery. The node is impinging upon the jugular vein (J) at the arrow. The long/short axis ratio is ≤1and no hilar line is seen. US-guided FNA had positive cytology, and Tg was found in the needle washout

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree