Fig. 4.1

A 51-year-old man with a history of lymphoma was referred for biopsy of an enlarged right cervical lymph node. A high-frequency (6–15 MHz) linear transducer was used to image this superficial lesion (a). Duplex Doppler sonography revealed some vascularity in the lesion and larger vascular structures deeper to the lesion (b). An 18-gauge core biopsy needle was used to obtain several core biopsy samples (c). A trajectory was chosen to obtain the longest possible core biopsy sample. Pathologic evaluation revealed mantle cell lymphoma, diffuse pattern

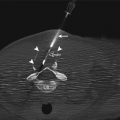

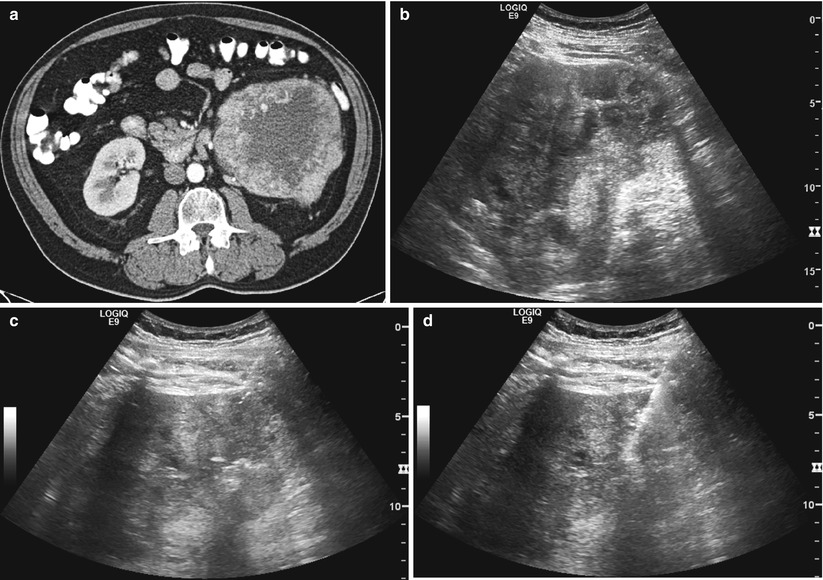

Fig. 4.2

A 68-year-old woman with a history of metastatic breast cancer was referred for a biopsy prior to enrollment in a clinical trial. An axial CT image of the liver (a) revealed a 6-cm mass in the medial aspect of segment VI. A smaller (2 cm) mass is seen more superficially closer to the liver capsule. With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, real-time ultrasound guidance was used to target the medial lesion for sampling (b). When possible, the target liver lesion and biopsy path should be selected such that the needle traverses a segment of normal liver before entering the tumor. This may reduce the risk of bleeding and tumor seeding after the biopsy

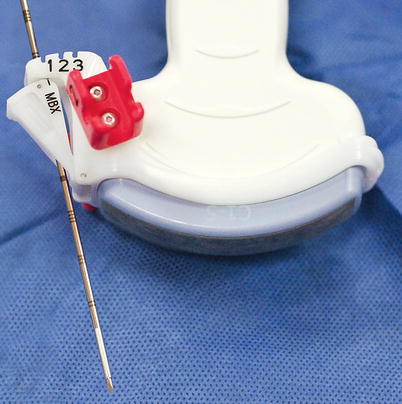

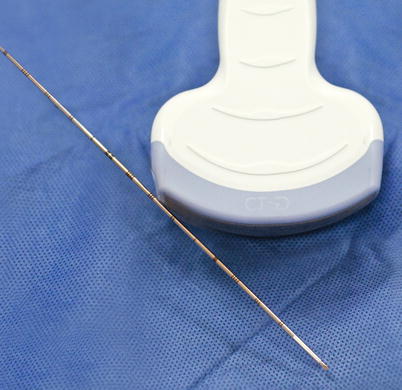

Fig. 4.3

In this photograph, the curved transducer is fitted with an adaptor with several predetermined angle settings. With this technique, the needle and the transducer work as a unit. The adaptor fits the needle and guides it to the target while preventing deviation of the needle from the set course

Fig. 4.4

In the “freehand technique,” the needle and the transducer are operated separately from one another. The needle can be inserted at any angle. One can also choose an insertion site that is not directly in the imaging plane, but maintaining the needle tip in the imaging plane of the transducer is more challenging and requires experience

Advantages

Ultrasonography is appealing as an image-guidance modality for several reasons. Ultrasonography is readily available, relatively inexpensive, and portable. It allows multiplanar imaging in any conventional or arbitrary plane. Unlike computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography does not use ionizing radiation. Most importantly, ultrasound guidance provides real-time visualization and monitoring of the needle tip as it is advanced into the skin, through the overlying soft tissues, and into the biopsy target. This visualization of the needle tip allows precise needle placement while avoiding damage to the nearby structures. Color flow Doppler imaging can help identify the vascular nature of the mass and the adjacent vascular structures (Fig. 4.1) [2, 3]. The imaging plane can be adjusted to exclude vessels from the path of the needle. Watching the needle tip during the sampling process in real time helps ensure that the needle tip does not extend outside the mass and that the biopsy is obtained from the lesion of interest (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5

A 54-year-old man with history of prostate cancer was referred for biopsy of a small liver lesion. Gray-scale sonographic image of the liver during the biopsy revealed a 1-cm hypoechoic tumor (arrowheads) adjacent to the gallbladder (GB). The echogenic needle is seen in the tumor. Real-time monitoring of the needle tip during fine-needle aspiration biopsy ensured safe, selective sampling of the small lesion without inadvertent puncture of the gallbladder

Another major advantage of ultrasound guidance is that the patient can be placed in various positions and that steep out-of-axial-plane angles can be used for needle guidance. Flexibility in the positioning of the patient also adds to the patient’s comfort during the biopsy. For example, the head of the bed may be elevated or the patient may be allowed to move slightly during the biopsy to get into a more comfortable position to relieve back or joint pain.

Disadvantages

Not all lesions can be well visualized on ultrasonography. Ultrasound guidance is optimal for targeting lesions that are located superficially or at a moderate depth in a thin- to moderate-sized patient. Ultrasound guidance is of limited use in identifying and targeting lesions in obese patients or lesions located deep within the body. Similarly, ultrasound-guided biopsy may not be possible when lesions are located behind a reflective surface such as bone or gas-filled bowel and when the transducer cannot be positioned to look from a different angle.

Applications

Any mass that is well visualized on ultrasonography can be targeted for biopsy. This includes any superficial soft tissue mass, head and neck lesion, breast tumor, or solid or cystic mass in the liver, kidney, or spleen [8–14]. Ultrasound guidance is commonly used to perform liver biopsies. This may include biopsy of specific lesions within the liver or biopsy of liver parenchyma to investigate the cause and severity of liver failure. The left lobe of the liver can often be reached from an anterior subcostal approach. The sagittal imaging plane can be helpful for lesions closer to the dome of the liver, although a steep-angle approach may be necessary. Lesions in the inferior aspect of the right lobe of the liver may be approached by a lateral subcostal route. Frequently, lesions in the right lobe of the liver are approached through an intercostal route with the patient placed in left lateral decubitus or supine position. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of a renal mass can be performed if the patient is not morbidly obese and the kidney can be adequately imaged on ultrasonography (Fig. 4.6). Ultrasonography can also be used to guide core biopsies of native and transplanted renal parenchyma to determine the etiology of parenchymal disease. Other abdominal and retroperitoneal organs such as the pancreas and adrenal gland may be targeted with ultrasound for biopsy [15, 16]. Ultrasound guidance can be used to biopsy lung, mediastinal, and pleural masses that abut the chest wall [17]. Some musculoskeletal lesions can be targeted using ultrasound guidance (Fig. 4.7) [18–20]. For retroperitoneal lesions, an anterior approach is preferred. Using specialized transducers, pelvic organs can be reached by transvaginal or transrectal approaches [21–23].

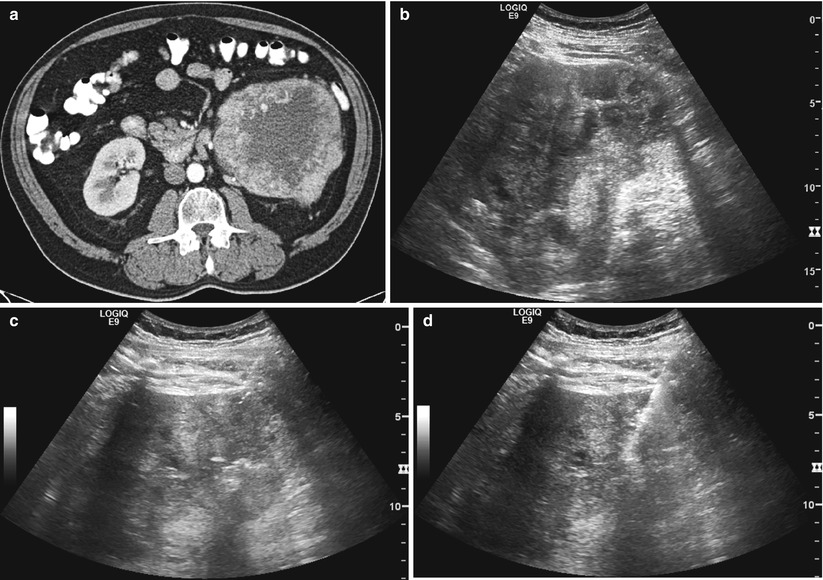

Fig. 4.6

An axial CT image of the abdomen (a) in a 53-year-old man revealed a large left renal mass with central necrosis. A gray-scale sonographic image (b) revealed a large mass with heterogeneous echogenicity. During ultrasound-guided biopsy (c), a 16-gauge guide needle is visualized with difficulty. When the stylet is replaced by the core biopsy needle, microbubbles introduced into the guide needle greatly enhance the echogenicity of the guide needle (d) and allow better visualization of the needle in the target

Fig. 4.7

An 11-year-old boy presented with pain and discomfort in the left thigh. Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left femur revealed an expansile lesion of the distal femoral diaphysis, with osteoid matrix, suspicious for osteosarcoma. The radiographs do not reveal a significant soft tissue component. He was referred for image-guided biopsy. Transverse gray-scale ultrasound of the left femur (c) revealed a rind of soft tissue thickening, with a nodular component (arrowhead) with underlying cortical breakdown (arrows). The soft tissue component of the tumor was targeted for biopsy (d) using a 14-gauge semiautomatic core biopsy needle. Four samples were obtained. A pathologic review revealed high-grade osteoblastic osteosarcoma

Techniques

Prior to ultrasound-guided biopsy, a limited ultrasound is performed to localize the lesion, select a suitable transducer, and plan the needle’s path. The distance between the puncture site and the target is measured to help select an appropriate biopsy needle. In some practices, a sonographer is responsible for imaging the patient during the biopsy, while the physician advances the needle to the target. Experienced interventional radiologists do not require a sonographer’s assistance, as the interventional radiologist will hold the transducer in one hand and the biopsy needle in the other hand. In this manner, hand-eye coordination is optimized.

Biopsy procedures are performed under sterile conditions. The transducer is covered with a sterile plastic cover. To prevent image degradation, ultrasound gel is placed inside the sterile cover to provide acoustic coupling. In addition, sterile gel is placed on the skin’s surface. Others prefer to clean the transducer with alcohol and place it directly on the skin [24], and no increase in post-biopsy infection rates has been reported [25].

Ultrasound-guided biopsies are performed under continuous real-time visualization of the biopsy needle as it is advanced to the target. If a needle-guidance system is used, a scanning plane is chosen so that the target lesion is lined up with the needle path. The depth of the needle insertion can be adjusted by choosing from the available predetermined angle choices. A needle guide of the correct size is attached or inserted into the transducer guide prior to insertion of the needle. The entire shaft of the needle can be constantly visualized when using a guidance system, making the needle-insertion process simple and efficient. It can be completed in one breath hold if needed. On the other hand, there is limited flexibility with the plane of imaging when using a rigid guidance system. Also, the needle must be placed close to the transducer and cannot be inserted at a more remote puncture site.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree