CHAPTER 1 Before beginning to learn how to interpret pathologic skeletal films, it is important to briefly consider unnecessary skeletal radiographic examinations. Dr. Ferris Hall from Boston first brought to my attention the idea that just because we could x-ray something didn’t mean that we should. His article titled “Overutilization of Radiologic Examinations” in the August 1976 issue of Radiology1 details many examples of overuse and misuse of radiologic examinations. This article, even though it is more than 35 years old, and a similar one by Dr. Herbert Abrams in the New England Journal of Medicine2 should be mandatory reading for every intern before he or she begins to order examinations. Except for a depressed skull fracture or the presence of intracranial metallic fragments, there is no reason to order a skull series for trauma. This was once one of the most abused examinations in radiology, costing millions of dollars per year unnecessarily. Although the number of unnecessary skull films has decreased, they remain a costly burden in many emergency departments. There is virtually no finding on a skull series that will alter the next step in the patient’s workup. Presence or absence of a fracture should not influence whether the patient receives a computed tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination. A CT or MRI scan is obtained for other reasons: continued unconsciousness or focal neurologic signs. The plain films only delay the eventual diagnosis, and in a patient with a subdural or an epidural hematoma, that delay could be fatal.3 The mortality from intracranial bleeding is significantly increased as the time to surgical decompression is increased; therefore any delay caused by obtaining unnecessary examinations (skull films) is potentially harmful. There are no findings on a plain skull series to indicate (or not indicate) subdural or epidural hematoma (Figure 1-1). Fewer than 10% of patients with fractures have subdural or epidural hematomas, and up to 60% of patients with subdural or epidural bleeding have no fractures.4 Therefore, why order the examinations? Medicolegal reasons? On the contrary! It is well documented that delays in diagnosis in this setting can be fatal, so ordering unnecessary examinations might in fact be asking for a lawsuit. The American College of Radiology has published appropriateness criteria for when to order particular examinations and has endorsed CT scans of the head as the initial study of choice in trauma.5 FIGURE 1-1 Despite much documentation in the radiology and emergency department literature that show skull films’ lack of utility in trauma, they still are commonly routinely ordered in many emergency departments throughout North America. A survey performed in 1991 by Hackney and published in Radiology6 reported that more than 50% of the hospitals in the study “often or always” obtained skull films for trauma. Every hospital had CT available. What are they thinking? Obviously they are not thinking about what a skull film will show them that might affect their treatment, because it won’t change a thing whether it is positive or negative. It is true that an opaque sinus or an air-fluid level can be seen in a sinus series when sinusitis is present. However, the patient with these findings is often asymptomatic, and just as often, the sinus series is interpreted as normal in another patient who has typical clinical findings of sinusitis. Both of these patients are treated based on their clinical, not radiographic, presentation, which is appropriate. Therefore the information from the sinus series is ignored. If that is the way you practice—and many recommend that as being proper—don’t order the sinus series: treat the patient. Reserve the sinus series for the patient who doesn’t respond to treatment or has an unusual presentation. Also, if it is only sinusitis you are concerned with, most times a simple upright Waters’ view (Figure 1-2) to examine the maxillary and frontal sinuses, rather than a full sinus series, will suffice, saving money and decreasing the patient’s exposure to radiation.7 FIGURE 1-2

Unnecessary examinations

Examples of unnecessary examinations

Skull series

Skull fracture. A thin radiolucent line characteristic of a skull fracture is noted (arrow) extending obliquely across the temporal bone. A fracture in this area is often associated with an epidural hematoma because the middle meningeal artery lies here. This finding by itself, however, has little or no significance and must be correlated with clinical findings.

Skull fracture. A thin radiolucent line characteristic of a skull fracture is noted (arrow) extending obliquely across the temporal bone. A fracture in this area is often associated with an epidural hematoma because the middle meningeal artery lies here. This finding by itself, however, has little or no significance and must be correlated with clinical findings.

Sinus series

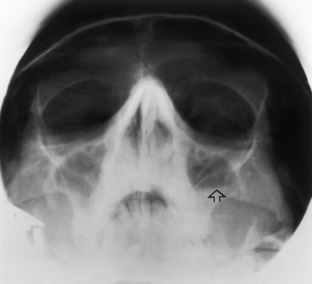

Waters’ view of the sinuses. This film is obtained with the patient’s head tilted slightly upward (as if he or she were drinking water—apologies to Dr. Waters). It is an excellent film to obtain when the maxillary sinuses need to be seen. When done in an upright position, air-fluid levels can be seen (arrow).

Waters’ view of the sinuses. This film is obtained with the patient’s head tilted slightly upward (as if he or she were drinking water—apologies to Dr. Waters). It is an excellent film to obtain when the maxillary sinuses need to be seen. When done in an upright position, air-fluid levels can be seen (arrow).

Unnecessary examinations