Acetabular labral tears are a mechanical cause of hip pain. Hip MR imaging should be performed on 3T magnets using small field of view and high-resolution imaging. If using a lower strength magnet, direct arthrography should be performed. The following should be used in the assessment for labral tear abnormalities on MR (or MR arthrography): labral morphology, abnormal T2 signal (or contrast) extension into the labral substance or chondrolabral junction. Description of the labral tear and extent of tear is useful for the hip preservation surgeon. Understanding the pitfalls around the acetabular labral complex will help avoid misinterpretation of labral tears.

Key points

- •

When performed at 3T, direct MR arthrography may not be necessary to confidently assess the acetabular labrum. Direct MR arthrography should be performed when assessing the acetabular labrum at 1.5 T or when assessing the postoperative labrum.

- •

Small field-of-view images and inclusion of an axial oblique plane, in addition to the conventional imaging planes, are important for confident diagnosis of labral pathology.

- •

Anatomic understanding and knowledge of common pitfalls are necessary for accurate assessment of the acetabular labrum.

Introduction

The acetabular labrum is an important fibrocartilaginous structure within the hip that is thought to provide joint stability, although the exact role of the labrum continues to be studied. Labral pathology is a known cause of hip pain in the active population. Labral abnormalities are associated with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and a significant factor in the development and progression of osteoarthritis. MR imaging remains the primary tool for diagnosis of labral pathology. With progressive improvement in this technology, direct MR arthrography may no longer be necessary for the accurate diagnosis of labral pathology when imaging is performed on 3T magnets. However, when assessed on 1.5 T MR scanners, MR arthrography is still considered the imaging technique of choice for the assessment of the acetabular labrum. This article will provide an update on the normal MR anatomy/assessment—including common pitfalls—of the acetabular labrum.

Discussion

Normal Anatomy

The acetabular labrum refers to the fibrocartilaginous structure that surrounds the cotyloid fossa. Inferiorly, it is replaced, though continuous, with the transverse acetabular ligament. This labro-ligamentous complex is surrounded by the joint capsule. ,

The labrum attaches to the bone on the acetabular rim at its superficial/capsular surface and attaches directly to the acetabular hyaline cartilage on the articular surface. It is through the direct bone-labrum interface on the capsular side of the labrum that nerves and blood vessels enter the labrum. The 1 to 2 mm region where the hyaline cartilage meets the labrum is also referred to as the “transitional zone”. In this transitional zone, the deep/articular surface side of the fibrocartilage of the labrum is attached to the bone of the acetabular rim by a layer of calcified cartilage. The fibrocartilage-hyaline cartilage interface differs geographically throughout the labrum. Anteriorly, the collagen fibers of the labrum are oriented parallel to the fibers of the hyaline cartilage of the acetabulum, which pre-disposes this area to shear injuries. Posteriorly, the collagen fibers at the interface are perpendicular and interdigitate with each other, which makes this portion of the labrum more resistant to such shear injury.

Under tension, the labrum stiffens as it encounters the femoral head peripherally. This provides stability to the joint, preventing the lateral migration of the femoral head. The peripheral contact of this stiffened rounded structure acts like a “suction-cup”, a phenomenon appropriately referred to as a “suction-seal” phenomenon. This seal functions to protect the acetabular cartilage by trapping a 0.4 mm buffer of synovial fluid inside the “suction cup” created by the labrum. This trapped fluid prevents contact between the femoral head and the acetabular articular cartilage. The high-pressure of the trapped fluid also helps retain the optimal hydration of the articular cartilage by preventing the process known as “consolidation”.

It is currently believed that these anatomic features—the intimate association between the fibrocartilaginous labrum and the hyaline cartilage of the acetabulum as well the chondroprotective nature of the “suction-seal” phenomenon—that form the basis for the importance of the acetabular labrum for hip stability and prevention of early onset osteoarthritis.

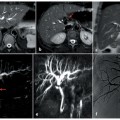

The hip joint capsule ( Fig. 1 A–D ) is intimately associated with the acetabular labrum and plays an important role in functional mobility and joint stability. The 3 primary capsular ligaments that stabilize the hip joint are the iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments. , The iliofemoral ligament originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine and branches into lateral and medial components, forming an “inverted Y” shaped ligament of Bigelow that has a broad attachment along the anterior intertrochanteric line. The ischiofemoral ligament extends from the anterior aspect of the ischial tuberosity to and attaches to the posterior intertrochanteric line. Finally, the pubofemoral ligament spans from the superior pubic ramus to blend with the medial iliofemoral ligament and inferior portion of the ischiofemoral ligament as it attaches on the medial/anteromedial margin of the femoral neck. ,

In addition to these ligaments, the hip joint and acetabular labrum are reinforced by the zona orbicularis and ligamentum teres. In distinction to the longitudinal fibers of the aforementioned capsular ligaments, the circular fibers of the zona orbicularis form a collar around the femoral neck and are thought to play a crucial role in resisting distracting forces. , The ligamentum teres attaches to the femur at the fovea capitis and extends to the inferior aspect of the joint, with a broad attachment to the transverse ligament of the acetabulum with small anterior and posterior fascicles that attach to the periosteum of the superior pubic ramus and ischium, respectively. The role of the ligamentum teres in the adult hip remains ambiguous. It is believed to play a role in hip stability, and injury to the ligamentum teres has been implicated in the development of micro-instability. It also may serve a purpose for proprioception and nociception.

MR Imaging Techniques of the Acetabular Labrum

Acetabular labral tears can often appear subtle on conventional MR imaging and, traditionally, direct MR arthrography was recommended for optimizing imaging diagnosis of labral pathology. Now, with ever increasing access to stronger magnets and improved coils, the need for MR arthrography has become less clear. Recent evidence suggests that MR imaging performed at 3T may be as just as good as MR arthrography performed at 1.5 T for diagnosing labral pathology. , With our present understanding, if imaging at 3T, conventional MR imaging may be adequate; however, if imaging at 1.5 T, MR arthrography should be performed for assessment of the acetabular labrum. MR arthrography should also be performed in post-operative cases. Finally, in the experience of the authors, MR arthrography can be helpful when labral findings on conventional MR imaging are equivocal or ambiguous.

Irrespective of whether performing conventional MR imaging or MR arthrography, a small field-of-view sequence (14–18 cm) of the affected hip should be included in MR protocols designed to assess the acetabular labrum. A phased-array surface coil or multichannel cardiac coil should be used for these examinations. In addition to the conventional tri-planar images, oblique axial images, obtained in the plane along the long axis of the femoral neck, should also be acquired to facilitate not only the identification of labral tears, but also to facilitate recognition of the anatomic characteristics that may predispose patients to FAI and labral tears. If available, 3-dimensional imaging with multiplanar reformats, with or without radial reformats, can prove useful for identifying and localizing labral pathology. ,

A more detailed review of hip MR imaging techniques is provided by Chiang and colleagues earlier in this edition of Clinics .

Normal MR Imaging Appearance

The labrum is generally triangular in cross section as it arises from the rim of the acetabulum, although it can have a variable shape at MR imaging. , , These labral shapes include triangular (most common), round, flat, or absent. A previous study by Abe and colleagues showed a triangular labral shape in 96% of patients 10 to 19 years old, but in only 62% of patients older than 50. , They proposed that the loss of the normal triangular shape labrum may be due to degeneration. There is controversy whether an absent labrum is congenital or secondary to degeneration. The labrum varies in thickness by 2 to 3 mm. , It is thicker both superiorly and posteriorly and thinner anteriorly. , However, there is also variability in labral size. This known variability in labral morphology poses the primary challenge for imaging assessment of the acetabular labrum. In fact, asymptomatic patients may have as much as a 15% difference in shape and 25% difference in size between their left and right acetabular labrum. ,

The labrum is generally diffusely low signal intensity on all pulse sequences due to the fibrocartilage composition. Intermediate or high signal intensity can be present within the acetabular labrum as seen in asymptomatic individuals. , This intermediate to high signal intensity may be due to mucoid degeneration, presence of intralabral fibrovascular bundles, or may be in part due to magic angle. , This labral signal may mimic a labral tear on conventional MR imaging. Akin to the issues faced with the variability of size and morphology in the asymptomatic labrum, the heterogeneity of the signal characteristics of the asymptomatic labrum poses a challenge for accurate imaging assessment.

Labrum Tear-Etiologies

The etiology for labrum tears can be degenerative, dysplasia, traumatic/overuse, impingement-related, or capsular laxity/hypermobility. , Idiopathic tears may also occur.

Degenerative tears may be related to old trauma, osteoarthritis, or inflammatory arthropathies. However, none of these are necessarily prerequisite for a degenerative labral tear. As was alluded to, abnormalities in the imaging appearance of the acetabular labrum occur in increasing frequency, even in asymptomatic patients, with increasing age. This suggests that degenerative tearing may simply reflect the expected evolution of this fibrocartilaginous structure with the aging joint. , , , In patients over 50 years of age, it has been reported that more than 70% have true labral tearing by imaging, and, in the setting of moderate or severe osteoarthritis, labral pathology is essentially universal.

Labral tears are very common in the setting of hip dysplasia, with one study reporting tears in 72% of those included with mild or moderate hip dysplasia. The labrum in dysplastic hips is commonly hypertrophied to compensate for bony under-coverage. This makes it susceptible to degeneration and tearing through impingement-like phenomena and chronic-shear stresses. Though these tears are most commonly anterior, they can also be seen posteriorly or even diffusely. , ,

Traumatic labral tears are typically focal, isolated to one location. Traumatic labral tears in the absence of a dislocation/subluxation are most often anterior/anterosuperior. These tears occur in the same region as those seen in athletes/overuse, FAI, and mild hip dysplasia. , In the setting of dislocation, tears are usually posterior or posterosuperior. The acute traumatic labral tear is often accompanied by acute articular cartilage injury and/or fracture.

FAI is now recognized as a common cause of labral tearing. Surgical management of a labrum tear now routinely addresses the bony anatomic basis for this condition at the time of labral reconstruction, repair, or debridement. Much more detail on FAI and pattern of injury is discussed in a later chapter of this edition of Clinics.

Capsular laxity/hypermobility can be related to chronic mechanical stress, hormonal influence or genetic, such as with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Ligamentous laxity leads to joint instability and ultimately abnormal stress upon the acetabular labrum. , Repetitive rotational athletic activities, such as golf, can lead to degeneration of the iliofemoral ligament with subsequent increased stress upon the anterosuperior labrum and a predisposition for tear.

Labrum Tear–MR Imaging: Recognition, Characterization, and Localization

Given the known variability in the appearance of the labrum, access to a good clinical history can help guide accurate MR imaging interpretation. This history may identify one of the previously discussed etiologies that may increase suspicion for tear. Knowledge of the location of a patient’s pain may also be helpful. Generally, patients with labral pathology will report anterior hip or groin pain that may be accompanied by a clicking sensation. , Localization of pain more posteriorly or laterally is much less commonly associated with labral pathology and should inform the interpreter of the hip MR imaging to closely interrogate the imaging for non-labral causes of hip pain. Correlation with pelvis/hip radiographs is also useful to assess the morphology of the hip prior to MR interpretation to aid in accurate diagnosis.

Labral pathology most commonly presents as labral detachment/separation from the chondrolabral junction but can also be seen as tears within the substance of the labrum, peripheral to the chondrolabral attachment. , , Labral “tears” and “detachments” are often used interchangeably colloquially—because up to 90% of these “tears” are labral detachments—though this distinction should be made clear in any description of a labral tear used for clinical management. For the purposes of this paper, these terms are used interchangeably. Labral tears have been classified according to location, etiology, and morphologic features.

The location of tears can be divided into quadrants: anterior, anterior superior, posterior superior, or posterior or can be described by the extent of the tear using a clock-face. Before using the clock-face description, discuss with your hip surgeon to ensure that there is a mutual understanding of the system used for localization of labral pathology.

The most common location for labral tears to occur in the western hemisphere is anterosuperiorly ( Fig. 2 ). , , The prevalence of anterosuperior labral tears is likely multifactorial. This may be related to the relative poor vascular supply, intrinsic structural weakness related to the collagen fiber orientation at the chondrolabral junction, and also the greater mechanical stresses subjected to this region—which are believed to be further exacerbated in the setting of morphologic features that result in femoroacetabular impingement. , , A more thorough review of femoroacetabular impingement can be found in a later chapter of this edition of Clinics.

Posterior labral tears are often associated with a discrete episode of hip trauma, typically involving impact loading of the extremity, causing the femoral head to be driven posteriorly within the acetabulum. , Isolated posterior superior labral tears are also most frequently seen after a posterior hip dislocation—through a similar mechanism—or in patients with acetabular dysplasia. Interestingly, in Japan, where squatting or sitting on the floor is more common, posterior labral tears are more often seen, likely due to the biomechanical stress placed on the labrum by this posture. , ,

Not all labral tears can be localized to a single quadrant of the hip. Tears have been reported to occur in all portions of the labrum. , In fact, tears have been reported to occur in multiple regions in the same hip and tear may also extend from one portion of the labrum across quadrants into other portions of the labrum. , , It is not uncommon to see this type of extended labral tearing in patients with degenerative tears and developmental hip dysplasia ( Fig. 3 A, B ).