Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

Renal calculi result from crystallization of supersaturated inorganic and organic compounds and proteins within renal tubular fluid, renal interstitial fluid, or in the urinary collecting system along the papillary surfaces. Supersaturation and crystallization of stone constituents may result from a combination of increased constituent excretion, reduced urinary fluid volume, abnormal urinary pH, urinary stasis from anatomic abnormality or obstruction, and chronic infection.

- ◼

Calcium compounds including calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate make up the majority (70%–80%) of upper urinary tract stones. Next to calcium, struvite or magnesium ammonium phosphate and uric acid are the next most common components. Uric acid stones are unique in that they can be dissolved by alkalinization of urine, often obviating the need for urological intervention. Less common stone constituents include cystine and precipitation of medications, such as indinavir, triamterene, guaifenesin, and sulfa drugs.

- ◼

Genitourinary tract anomalies that predispose to urolithiasis include horseshoe kidney, ectopic pelvic kidney, and the ectopic moiety in a cross-fused renal ectopia.

- ◼

Most symptomatic urolithiasis presents as renal colic or flank pain. If there is acute collecting system obstruction, stone passage is often associated with acute symptom relief. Aside from obstruction and pain, calculi can lead to hematuria from urothelial irritation and can serve as a nidus for infection. Common locations for obstructing urolithiasis include areas of inherent ureteral narrowing, specifically the ureterovesical junction, the ureteropelvic junction, and where the ureter crosses anterior to the iliac vessels/pelvic brim.

Techniques

- ◼

Unenhanced computed tomography (CT) is the preferred method for diagnosis, treatment planning, and posttreatment follow-up of urolithiasis. When a calcification cannot be confidently diagnosed as a ureteral stone, excretory or urographic phase images after intravenous (IV) iodinated contrast administration are helpful to delineate ureteral anatomy and stone location ( Fig. 22.1 ).

Fig. 22.1

Delayed phase of a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan (coronal reformatted image) demonstrates a dilated right ureter and a distal obstructing stone.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Ultrasonography (US) is useful as a screening modality for obstruction because it readily demonstrates hydronephrosis. The presence of urinary jets from the ureterovesical orifices rules out significant obstruction.

- ◼

Radiographs lack the sensitivity and additional anatomic information of CT but can be useful to follow patients with known radiographically visible calculi.

- ◼

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has little role in the evaluation of urolithiasis but can demonstrate urinary tract findings associated with urolithiasis such as obstruction, ureteral strictures, and genitourinary anomalies.

- ◼

IV pyelogram (IVP) has been replaced by CT in most settings.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Unenhanced CT is the modality of choice for the diagnosis of renal stones, because of widespread availability, efficiency, and high diagnostic accuracy with reported sensitivity of 95% to 98% and specificity of 96% to 100%.

- ◼

In addition to being more sensitive than radiography, IVP, and US in the detection of urolithiasis, CT better delineates nonurinary tract causes of flank pain, which have been reported to account for up to 15% of identifiable causes by CT, such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, pancreatitis, and ovarian torsion. CT is particularly more sensitive than abdominal radiography for detection of ureteral calculi, small renal calculi, and radiographically lucent calculi, such as uric acid stones ( Figs. 22.2 , 22.3 and 22.4 ).

Fig. 22.2

34-year-old woman presented with right-sided flank pain. A, Axial unenhanced computed tomography scan shows a nonobstructing right renal stone. B, Plain film radiograph also demonstrates the right renal stone and could be used for follow-up imaging.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

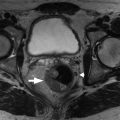

Fig. 22.3

51-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain. A, Sagittal ultrasound image shows two nonobstructing stones in the mid and lower left kidney as echogenic foci ( white arrows ) with posterior acoustic shadowing ( yellow arrows ). B, Coronal computed tomography shows the stones ( red arrows ).

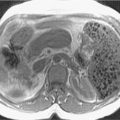

Fig. 22.4

A, Scout image shows a uric acid bladder stone as minimally opaque. Unenhanced axial (B) and reformatted coronal (C) Computed tomography images show the 17- by 12-mm stone, measuring 400 Hounsfield units, in a left posterolateral bladder diverticulum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree