Fig. 9.1

CDS for documentation. CDS demonstrates patency of pyloric canal after feeding: red coded influx of stomach content into duodenum (note colour map in left upper corner of US image: red encodes direction away from transducer, thus from stomach into duodenum). Colour box angulated for better Doppler angle

Remarks on oesophagus: visualised at cervical part (see US of the neck, Chap. 4), at median part, provided sufficient mediastinal access (e.g. by large tumour); at distal part, gastro-oesophageal junction (visible via paramedian left, slightly tilted sagittal view), observe relation to aorta and diaphragmatic hiatus.

NOTE: Typical structure defined by serosa, muscle and mucosa, as well as content and wall thickness.

9.1.3 Normal Findings

Collapsed distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction should not measure more than 7 mm in infants.

Gastric wall has five layers; wall thickness smaller than 3–4 mm, depending on filling and age.

Inner mucosa and echogenic layer thin. Contour of inner mucosa and gastric folds can be visualised, if stomach sufficiently filled with anechoic fluid.

US appearance of stomach contents varies depending on kind of food and amount of air (Fig. 9.2a).

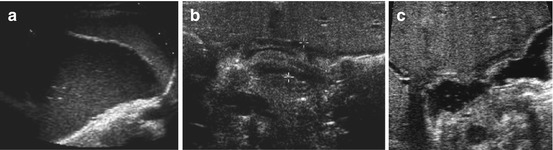

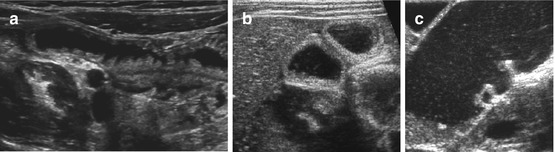

Fig. 9.2

Normal stomach and pylorus. (a) Fluid-filled stomach, adjacent spleen. (b) Normal pylorus (+ +) while stomach empty. Wall narrow, though pylorus appears long. Wall layers, particularly prominent echogenic mucosal inner layer, nicely appreciated. (c) Open normal pylorus after feeding tea – unhindered passage of anechoic fluid from stomach into duodenum

Pylorus/gastric outlet usually shows only slight thickening of wall in relation to stomach wall. In infants muscle thickness should measure <3 mm, length should be <15 mm and diameter <10 mm (Fig. 9.2b).

After feeding unhindered passage of stomach content into duodenum can be observed (Fig. 9.2c).

NOTE: In newborns wall thickness physiologically less; length of pyloric canal shorter. Pyloric length only assessable if stomach sufficiently filled.

9.1.4 Normal Variants

Not reliably assessable by US.

9.1.5 Malformations

9.1.5.1 Microgastria

Small content, easier to visualise on fetal scans than postnatally.

9.1.5.2 Pyloric Atresia

Rare condition, usually diagnosed prenatally.

Difficult to differentiate from high-grade pyloric stenosis and gastric webs.

9.1.5.3 Congenital Hiatal Hernia

Variant from diaphragmatic hernia (see Chap. 6), can be depicted by US if large.

TIP: Fill stomach and observe dynamically.

9.1.6 Pathologic Findings

9.1.6.1 Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux (GOER)

Definition

Reflux of stomach contents to oesophagus – small amounts of intermittent regurgitation physiologic in first 3 months of life. To be distinguished from intermittent regurgitation during swallowing which may be physiologic.

Grading:

Mild, intermediate and severe (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

Grading of gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOER) in infants

Grade | Oesophagus | Function | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

No reflux | Thin | Prompt clearance into stomach, during swallowing no reflux after feeding | Normal |

Up to four reflux episodes | No dilatation | Prompt clearance after GOER | Physiological GOER |

More than four reflux episodes | Mild dilatation | Slightly delayed clearance after GOER | Mild GOER |

Numerous reflux episodes | Significant dilatation | Significant delay | Intermittent GOER |

Continuous reflux | Constantly open gastro-oesophageal junction | Yo-yo phenomenon of stomach content to distal oesophagus | Severe GOER / hiatal hernia |

Criteria:

Frequency, duration, dilatation of distal oesophagus and oesophageal clearance.

Provocation:

Drinking (water siphon test), left decubitus position with slight pressure on abdomen with transducer, similar to fluoroscopy.

US Findings

Regurgitation of fluid from stomach into oesophagus with variable widening of the gastric inlet (Fig. 9.3a, b). Details depend on kind of food, stomach and gastric wall thickness + severity of GOER. Assess number and duration of reflux episodes, grade of dilatation of distal oesophagus, oesophageal clearance and wall thickness. Observe for potential intermittent herniation of gastric parts to thoracic cavity in intermittent sliding hiatal hernia, particularly after filling stomach (Fig. 9.3c, d). Document GOER – best achieved by video clips or CDS (documents direction of flow) using adapted settings.

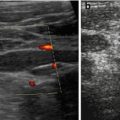

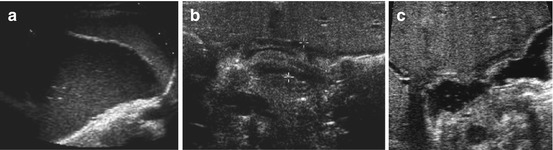

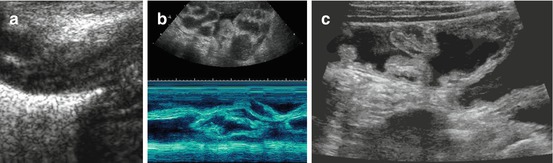

Fig. 9.3

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOER). (a) Parasagittal paramedian view in upper abdomen: GOER of air mixed stomach content into distal oesophagus without dilatation (+ +), normal wall of hiatal structures. NOTE: Similar images seen during feeding (then normal direction of food going into stomach/not inverse as in GOER). (b) Same section as in (a): stomach filled with fluid – regurgitation into slightly dilated distal oesophagus, normal wall of hiatal structures. (c) Axial median section, upper abdomen, transducer tilted cranially: (pseudo-)tumorous structure (+ +) with thick wall and inhomogeneous echoes at gastro-oesophageal junction. (d) Same patient and same US section as in (c): after feeding tea “tumour” fills with fluid and air confirming hiatal hernia with parts of stomach herniated into chest

NOTE: Use standard meal, avoid ingredients that cause or provoke GOER.

Role of US

In infancy good correlation with pH monitoring and fluoroscopy. The older the child, the poorer US performs.

Evaluation of oesophagus and its mucosa for secondary inflammation not possible.

NOTE: Reliability for assessment of sliding hernias and anatomic stomach anomalies restricted.

Additional Imaging: pH monitoring for GOER (only useful in acid reflux), oesophageal manometry and fluoroscopy (barium swallow).

9.1.6.2 Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS)

Definition

HPS best diagnosed sonographically.

Cramps with propulsive non-bilious vomiting. Typically occurs in boys aged 4–12 weeks.

Treatment usually by surgery, though medical conservative treatment may be an option in early and mild disease with high surgical risk.

DDx

Pyloric atresia, gastric web, pylorospasm and gastric outlet tumours.

US Findings:

Enlargement of pylorus and particularly pylorus muscle consistently throughout investigation. Length >15 mm, muscle >3 mm, axial diameter ≥12 mm and wall lumen ratio >2:1 (Fig. 9.4a, b).

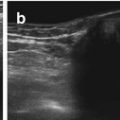

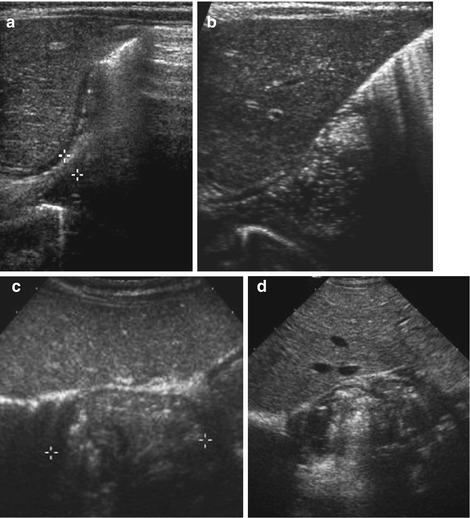

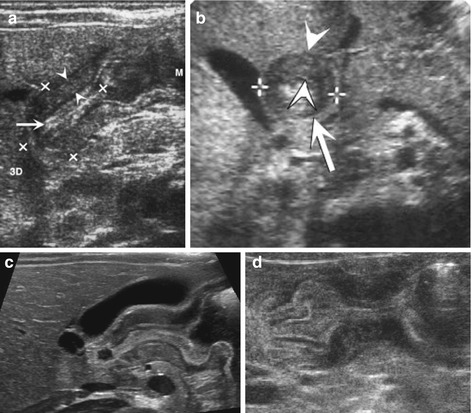

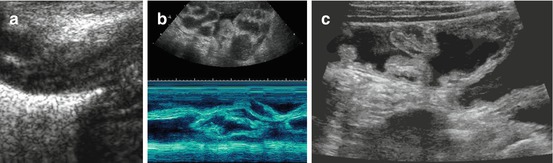

Fig. 9.4

HPSt. (a) Longitudinal section through pylorus, right paramedian upper abdomen: enlarged pylorus, thickened wall (arrowheads), enlarged diameter (+ +) and length (× ×) and narrow canal (arrow). (b) Axial section through pylorus, right paramedian upper abdomen: enlarged pylorus appearing as a round pseudotumorous lesion (arrow) with a central target sign. Thickened wall (arrowheads) enlarged diameter (+ +). (c) Longitudinal section through pylorus, right paramedian upper abdomen: elongated pylorus within thick wall and ”pyloric shoulder” appearance of gastric outlet with heavy peristalsis. Narrow canal, only minimal fluid in duodenal bulb. (d) Pylorospasm: longitudinal section through pylorus in right paramedian upper abdomen depicts HPSt-like appearance, only beginning and end of pylorus intermittently open. Central spastic part resolved after some time – then relatively normal passage into duodenum could observed

No or only minimal opening of pyloric canal (Fig. 9.4c).

Change in wall thickness from stomach to pylorus with typical shoulder-like contour at pyloric entrance.

Often displacement of pylorus, gastric enlargement with residual volume in fasted children.

Particularly after feeding, hyperperistalsis and secondary GOER.

In late stages hypotonic enlarged stomach.

NOTE: In early stages an very young infants/preterm babies findings may be subtle, only functional observation + follow-up will establish diagnosis; sometimes difficult to differentiate from pylorospasm (Fig. 9.4d).

Follow-up under medical treatment:

First no morphologic changes, but improvement of gastric clearance and content passage to duodenum.

Thickening and elongation may persist for several weeks (as also after surgery).

Documentation of pyloric passage best by CDS and video clips.

Role of US

Main method for diagnosis, rarely in equivocal findings fluoroscopic UGI or MRI for gastric tumours may become indicated.

9.1.6.3 Other Stomach Conditions

Gastritis/Ulcers

Not diagnosed by US, sometimes contour alterations can be seen in thickened stomach wall, provided sufficient filling without overlying gas/air. More easily visible if adjacent deep abscess.

Bezoars and Foreign Bodies

Bezoars usually nicely assessable by US, foreign bodies if stomach filled sufficiently.

Appearance depends on content, bezoars typically with very echogenic surface without sound penetration.

Hyperplastic Gastric Mucosa

Similar to gastritis – also potentially difficult to see.

May cause gastric outlook obstruction (severe mucosal thickening, young age – typically neonates under prostaglandin therapy for PDA).

Menetrier’s Disease: Giant Hypertrophy of Gastric Mucosa

Typically affecting older children.

US Findings

US may exhibit irregular thickened echogenic mucosa, particularly in fundus and body of stomach.

Gastric muscle may also be thickened and hyperechoic.

Secondary findings due to hypoproteinaemia (protein loosing enteropathy), such as oedema, ascites and pleural effusions.

Eosinophilic Gastr(oenter)itis

Not differentiable from other types of gastritis – thickening of stomach wall including pyloric muscle, elongation of pyloric canal – may mimic pyloric stenosis.

Gastric Perforation

Complex regional fluid collections at site of perforation.

Secondary changes such as ascites, peritoneal abscess and pneumoperitoneum.

Often underlying focal stomach changes may become visible, e.g. thickened wall, (“ring-down”) artefact at site of perforation.

Granulomatous Disease

Any granulomatous disease may affect stomach.

Chronic granulomatous disease of childhood (x-linked disorder) most common Findings include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal pain and potentially pneumonia.

Stomach most commonly involved part of GI tract.

Seen as circumferential wall thickening and luminal narrowing.

May appear as benign masses in stomach wall.

Duplication Cysts

Characterised by its wall “gut signature” (see below – bowel), exhibiting typical wall structure of related part of intestine. May have a connection with lumen.

US Findings

Usually unilocular cystic thick-walled lesions (see Fig. 9.13). Have comon blood supply with organ of origin, move together with organ or its peristalsis.

Content echogenicity may change secondary to haemorrhage, infection, proteinous debris, epithelial cells and sediment.

Size variable – if connection with bowel lumen (see Fig. 9.14).

Teratoma

Rare. Depending on histological composition may exhibit complex structure or appear purely cystic with nodular solid components/wall.

There may be calcification, bone, fat, and secondary changes.

Focal Foveolar Hyperplasia

Rare gastric mass due to obstruction or inflammation of gastric fovea (pits in mucosa, where gastric glands empty).

US Findings: Echogenic polypoid masses in mucosal location.

Inflammatory Pseudotumour

A benign inflammatory pseudo-tumorous mass, commonly in greater curvature (also called plasma cell granuloma or fibroxanthoma).

US Findings

Often poorly defined with mixed echogenicity and secondary haemorrhage or necrosis.

Rare diffuse manifestation with diffuse hypervascular wall thickening – with regionally enlarged nodes.

Other Benign Tumours

Many entities possible, though extremely rare (e.g. myofibroma, polyps, haematoma, neuromyoma, neurofibroma, haemangioma and lipoma).

US Findings: Tumour visible – entity cannot be defined/distinguished.

Diagnosis usually requires biopsy.

Malignant Masses

Most commonly lymphoma or gastrointestinal stroma tumours (GIST) – both manifest as single or multifocal masses.

US Findings

US depicts polypoid tumour or focal wall thickening that may mimic any other space occupying lesion:

Lymphoma: mass usually hypoechoic to normal gastric wall echogenicity, exhibits changes such as splenomegaly and enlarged lymph nodes, often relatively large tumour at diagnosis.

GIST: smaller at diagnosis, often heterogeneous and echogenic masses with nodular and cystic areas (haemorrhage, necrosis).

Other rare gastric wall tumours:

leiomyosarcoma, carcinoma (as familial/inherited condition).

Diagnosis relies on histology.

9.1.7 Role of US

May depict findings, but less reliable for ruling out conditions or specific entity diagnosis – except for GOER, HPS and duplication cysts.

Additional Investigation: Endoscopy, MRI/CT, for some condition fluoroscopy and biopsy.

9.2 Bowel

9.2.1 Preparation and Requisites

Indications

Suspected intussusception, volvulus, necrotising enterocolitis, intestinal Henoch-Schonlein purpura, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, etc.), bloody diarrhoea, acute abdomen (e.g. after trauma), other nonspecific queries, familial conditions (intestinal polyposis), during chemotherapy, etc.

Preparation and US Options

Acute US performed without specific preparation, particularly in query intussusception, volvulus and appendicitis.

Visualisation improved by oral fluid intake, potentially with some distending substances (as also used for MR-enteroclysis) – this allows proper distension and good visualisation of lumen, detection of stenotic areas and intraluminal pathology such as polyps.

Rectal enema (hydrocolon – “US enema”) with warmed saline solution, improves assessment of colon, can also be used therapeutically for reduction of intussusception or meconium ileus (see Chap. 2).

Perineal access (after enema) for assessment of defecation and rectal/anal stenosis/atresia/malformation. Sometimes enema improves visualisation of fistulae in inflammatory bowel disease or complex malformations.

Graded compression technique advised, positioning manoeuvres helpful for transporting fluid to area of interest.

Positioning

Usually supine, relaxed abdominal wall musculature helpful (can be achieved by support to knees).

Transducers

Linear transducers with highest achievable frequency for optimal resolution helpful.

Curved linear arrays allow better overview, or extended view techniques. Sector transducers rarely helpful.

Frequency depends on patient age and position of targeted bowel segment. The smaller and the closer to surface, the higher the frequency (e.g. in neonates 15 MHz, in school children for appendiceal assessment 10–5 MHz).

9.2.2 Course of Investigation

Approach

Transabdominal + perineal.

Also access from flank and through full bladder/full stomach.

Orientation

Helpful to first assess in organo-axial section.

Identify well-defined structures (e.g. pylorus, gastro-oesophageal junction, coecum, rectum).

Follow respective loops continuously from distal to proximal.

Assess bowel wall (thickness, structure), size (stenotic part?), peristalsis and compressibility.

Assess lumen and content. Bowel structure may help identification (jejuna folds, colon haustrae, etc., Figs. 9.5 and 9.6).

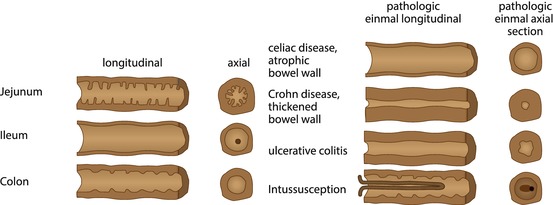

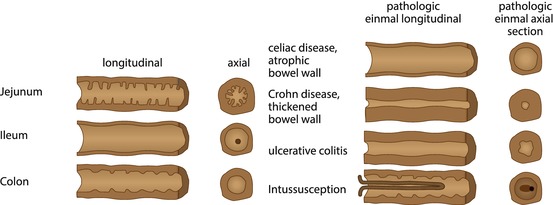

Fig. 9.5

Schematic drawing of bowel appearance with respective typical pathology. Left side: schematic drawing to demonstrate typical bowel features that may help to identify the various bowel segments; this may physiologically not apply to (preterm) neonates due to immaturity (no typical haustrae). Right side: typical schematic US appearance of common pathology of respective bowel section

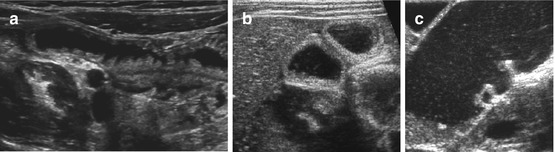

Fig. 9.6

Contour of different bowel partitions. (a) US appearance of normal proximal jejunum with typical folds (fluid filled). (b) Normal fluid-filled ileum: no folds, no haustrae. (c) Fluid-filled colon: haustrae can nicely be visualised

Add longitudinal sections for documentation of inner contour (folds) and assessment of stenotic segments (extended field of view helpful).

Always assess surrounding structures (mesentery, lymph nodes, etc.).

Finally, add CDS for assessing bowel wall vasculature and main feeding vessels; in some applications (e.g. NEC), assessment of mesenteric artery/vein and coeliac trunk helpful.

Complete investigation by sampling relevant vessels for spectral analysis of Doppler flow profile.

NOTE: Modern tools helpful (harmonic imaging, high-resolution imaging, perineal US, image compounding, graded compression, etc.). High-contrast preset advisable (to be changed for assessing subtle alterations of wall structure).

9.2.3 Normal US Findings

Typical stratified bowel wall, “gut signature”: at least three, often five layers depictable – echogenic superficial mucosa, hypoechoic deep muscular mucosa, echogenic submucosa, hypoechoic muscle and echogenic serosa (Fig. 9.7).

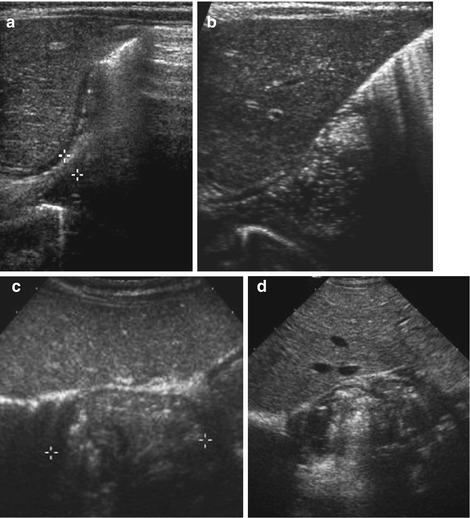

Fig. 9.7

US appearance of bowel wall and peristalsis. (a) Normal bowel wall stratification seen non-high magnification: at least three layers recognisable (with modern high-resolution transducers even five): hypoechoic inner “mucosa”, echogenic “submucosa” and hypoechoic muscle. (b) M-Mode used to document the intense and irregular small bowel peristalsis in a child with gastroenteritis and thus fluid-filled loops with some ascites. (c) Bauhin’s valve visualised after saline enema

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree