Sang Joon Park

Percutaneous embolization has become a common procedure to treat acute bleeding and vascular abnormalities. A permanent occlusion can be created with an embolization procedure with various embolic materials, including polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles, embolic microspheres, glue, coils, and occlusion balloons; coils are the most commonly used device.1 The major disadvantages of coils are that multiple coils are often required for the complete occlusion of the targeted vessel and that accurate placement can be challenging depending on the vessel size and blood flow rate. Moreover, the chance of coil migration is always high when embolizing large feeding vessels with a high flow rate. To overcome this shortcoming of coils, the Amplatzer Vascular Plug (AVP; St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, Minnesota) was introduced and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2004 for peripheral embolization. The first report on the successful use of the AVP was published by Hill et al.2 in December 2004. Since then, numerous reports have been published in various medical journals. The device has shown an excellent technical success rate for an expanding number of indications,3 and no significant contraindication to embolization using this device has been recognized.4 As described in Chapter 1, new plugs such as the Medusa Vascular Plug (EndoShape Inc., Boulder, Colorado) and the MVP Micro Vascular Plug System (Reverse Medical Corporation, Irvine, California) have been recently introduced. This chapter will focus on use of the AVP given the extensive experience with this device.

DEVICE DESCRIPTION

The original AVP was derived from the Amplatzer septal occluder and the Amplatzer duct occluder. The AVPs consist of a self-expanding cylindrical nitinol mesh that can be deployed both rapidly and accurately. The elasticity of the nitinol allows the device to become firmly anchored to the vessel wall due to its outward radial force.5 There are radiopaque platinum marker bands at both ends for high visibility under fluoroscopy. The plug is attached to a delivery wire with a stainless steel screw on one of the platinum marker bands.6 One significant advantage of the AVP as an embolic device is that it can be repositioned before final release, which is performed by rotating the delivery wire.

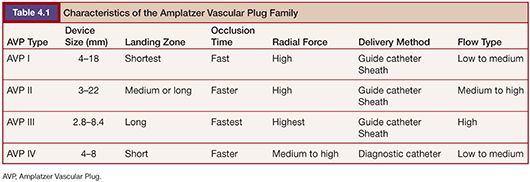

After the introduction of the first AVP, the AVP family has grown to four types: AVP I, AVP II, AVP III, and AVP IV (Fig. 4.1). Each type has a unique design and features making it suitable for different vascular anatomies, hemodynamics, and clinical situations. Subsequently, a newer generation does not mean that it can replace the older type. In appearance, the AVP I has a single lobe, the AVP II has three lobes, and the AVP III and IV have two lobes. In addition, the AVP I and IV have single-layered braids, whereas the AVP II and III have a multiple-layered design, except for the 3-mm AVP II. The characteristics of the AVPs are described in Table 4.1.

The AVP I was the first product of the AVP family. Most of the published case reports have been performed with this device.7 The diameters of the AVP I range from 4 to 16 mm with increases in 2-mm increments. This device is well suited for landing zones that are limited in length.8

The AVP II is the second-generation product in the AVP family; it received FDA approval in 2007. It has been used in various clinical settings,9–13 but no randomized trials comparing the AVP II with well-established embolization devices has been reported to date. This device is multiple layered and made of more densely woven nitinol mesh than the AVP I, except for the 3-mm device, which is single layered. It consists of three segments with a central lobe and two discs on each side of the lobe. Compared to the AVP I, the AVP II exerts greater radial force, over four axes, and may thus be expected to migrate less and cause more rapid occlusion.14

The AVP III has a unique, oblong, cross-sectional shape and multiple nitinol mesh layers. It also has rims that extended beyond the device body, which may enhance stability. There are only few reports on the clinical application of this device.15 This device received CE mark approval of Europe in 2008.

The AVP IV has a double-cone shape and is mounted on a fixed-core wire guide with a 20-cm floppy distal tip. Unlike other AVPs, it can be delivered through a 4-Fr or 5-Fr diagnostic catheter with a 0.038-in inner lumen without the need to exchange for a sheath or a guiding catheter. This feature enables this device to be used in smaller and tortuous vessels in the arterial or venous vasculature.16,17 This is the biggest advantage of this device over other generations of the AVPs. Like other plugs, the AVP IV can be recaptured and repositioned if necessary. It received CE mark approval in 2009 for Europe and was cleared by the FDA in 2012.

TECHNIQUE

When treating vascular pathology with the AVP, the size of the target vessel and the length of the landing zone for the device must be determined to choose the most appropriate AVP for use. It is currently suggested that the AVP be oversized by 30% to 50% relative to the diameter of the target vessel. The elasticity of nitinol allows the plug to fully expand within the vessel for adequate wall apposition.

Once the device has been selected, the initial consideration for its placement is the determination regarding what catheter will be used to deliver the plug to the site of deployment. A 4-Fr sheath or 5-Fr guiding catheter is required for the AVP I and AVP II, whereas a 4-Fr sheath or 6-Fr guiding catheter is required for the AVP III. Therefore, a relatively straight segment of target vessel with a relatively constant diameter is needed for deployment for the AVP I, AVP II, and AVP III.3

The newest device, the AVP IV, can be delivered through a 4-Fr or 5-Fr diagnostic catheter without an additional sheath or guiding catheter. The combination of low profile and flexible delivery wire tip makes it possible for this device to be used in smaller vessels such as the splenic, lumbar, and gluteal arteries.16 The size of this device is limited, covering vessels with diameters of 2.6 to 6.2 mm, providing the requirement for at least 30% oversizing.

The delivery catheter is not the only part of the system that needs to be advanced to the anticipated site of deployment. The plug and delivery wire must be advanced through the delivery catheter or sheath, and this can be problematic in some cases. The delivery wire is stiff and may be difficult to advance through the delivery catheter. This is especially the case when the target vessels are tortuous. To overcome the tortuosity of the artery, two methods can be used. One is to use a guiding catheter within the sheath to increase the stability and ease of deployment according to Zhu et al.,18 and the other is the use of a larger introducing system to gain access to the landing zone.19

When the desired position of the device is reached, the device can be easily deployed by rotating the cable counterclockwise to complete implantation. Subsequently, repositioning the device is possible before release. Moreover, a test injection of contrast medium is possible through the delivery catheter to verify the location of the device before deployment.5

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

The AVP has been used successfully for various indications suitable for the use of a mechanical embolic agent. Often, the limiting factors in determining whether a plug would be appropriate to use include the size of the target vessel, the tortuosity of the vessels leading to the site targeted for occlusion, the length of the landing zone, and the nature of the pathology being treated.

Several arterial indications for the AVP have been described. These devices have been used successfully in the internal iliac artery for endoleak prevention before endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR)20 as well as to treat pseudoaneurysms.21 They have also been used successfully for embolization of the gastroduodenal artery before radioembolization with yttrium 90 microspheres. Both the AVP II and IV have been used successfully for this indication.14,22,23 Additional indications include embolization of the proximal splenic artery as treatment for portal hypertension and splenic artery syndrome after orthotopic liver transplantation,18 splenic artery aneurysms,24 and splenic trauma to avoid splenectomy.25,26

The use of the AVPs in the venous circulation has also been reported. These devices have been used successfully in combination with coils and gelatin sponge for portal vein embolization.27,28 In addition, these plugs have been used for the treatment of gonadal vein embolization for varicoceles and pelvic congestion syndrome either alone or in combination with coils or liquid embolic agents.29,30

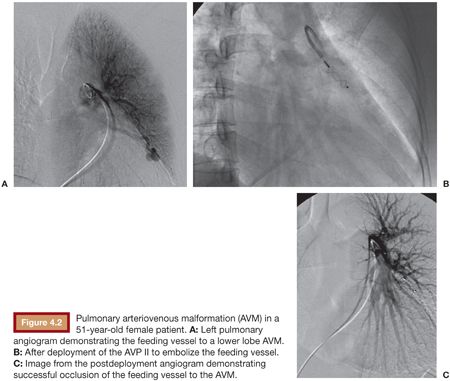

These devices essentially began in the cardiac setting, treating conditions such as a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and patent ductus venosus (PDV).7 Now, other congenital arteriovenous communication can often be effectively treated with these plugs. For example, pulmonary arteriovenous malformations can be treated with the AVP (Fig. 4.2), which can be advantageous due to the low risk of migration into the pulmonary venous outflow after deployment.19,31–33 Other potential applications in this area include splenorenal shunts,34 renal arteriovenous fistulae,35 mesocaval shunts,36 and the rerouting of a scimitar vein to the left atrium.37 Acquired lesions can also be treated with the AVP. This includes the treatment of hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulae that require closure for steal syndrome or enlarging aneurysms38 as well as for either occlusion of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the setting of refractory postprocedure encephalopathy or for embolization of varices during TIPS creation.39

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree