Fig. 16.1

Vasculitis classification

Takayasu’s Arteritis (TA) and Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA), also called Horton’s Arteritis, basically represent LIA.

Medium vessel vasculitis is mainly represented by Kawasaki disease (KD), which principally involves the coronary arteries, and Panarteritis Nodosa (PAN) is typically found in mesenteric vessels.

Therapy

Medical therapy (corticosteroid and immunosuppressive drugs) is necessary in the management of vasculitis. In particular cases, when vascular stenosis is critical, surgical/endovascular therapy is mandatory.

16.1 16.1 Takayasu Arteritis

Clinical Picture and Diagnosis

TA was described for the first time in 1830 by Yamamoto, but the name was given by Professor Takayasu, an ophthalmologist who described arteriovenous malformation in a 21-year-old woman. In 1951 Shimizu and Samo described the clinical features of TA as a pulseless syndrome because of the typical involvement of the subclavian axis with absence of the systolic pulse at the wrist.

TA is rare, with onset age between 10 and 40 years old; it is more common in the Asian population. Hall et al. reported an incidence of 2.6/million/year in the US population. To our best knowledge, no data have been published for the EU population.

The clinical characteristics of TA are due to vessel involvement, as described in Table 16.1.

Table 16.1

Clinical features of TA

Signs and Symptoms |

|---|

Pulse reduction or absence (brachial pulse in particular) |

Murmurs in carotid arteries or aorta |

Hypertension (due to renovascular disease) |

Retinopathy |

Cardiac congestive disease linked to hypertension, aortic regurgitation and dilated cardiomegaly |

Neurological symptoms due to hypertension and ischemia |

Pulmonary artery involvement |

Other symptoms, such as: headache, myocardial ischemia, thoracic pain and erythema nodosum |

The clinical features are sometimes unclear and it could be difficult to diagnose the disease.

Table 16.2 describes the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for TA diagnosis.

Table 16.2

ACR criteria for TA: it is possible to diagnosis TA if 6 criteria are satisfied; ≥3 criteria have a sensitivity rate of 91% and specificity of 98% in TA diagnosis

Age at disease onset <40 yrs |

Claudication of extremities |

Decreased brachial artery pulse |

Difference of >10 mmHg in systolic BP between arms |

Murmurs in subclavian arteries or aorta |

Arteriographic narrowing or occlusion of the entire aorta or its primary branches |

Vinoli et al. have described the clinical features in a review of 104 patients: 93% presented arterial stenosis, 53% had occlusions, 16% dilatations and 7% aneurysms.

The typical histological findings of TA are inflammatory changes at the level of tunica media and tunica adventitia.

Matsunaga et al. described two different chronological phases (Table 16.3):

early phase, characterized by inflammation at the level of the tunica media and tunica adventitia, which leads to mural thickening.

late phase, with elastic fiber destruction and subsequent fibrosis. The late phase is characterized by typical symptoms with mixed stenosis or dilation/aneurysm (Fig. 16.2). The severity of the late phase is related to the time between the diagnosis and the start of therapy.

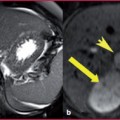

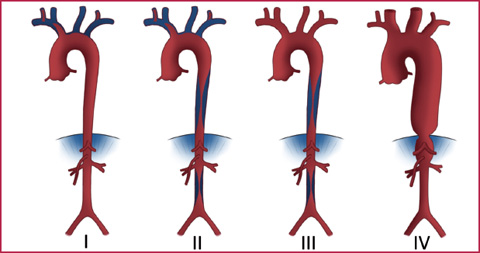

Fig. 16.2

Fukushima’s classification of late phase TA: type I (supra-aortic vessels), type II (supraaortic vessels and abdominal aorta), type III (abdominal aorta), type IV (aneurysm)

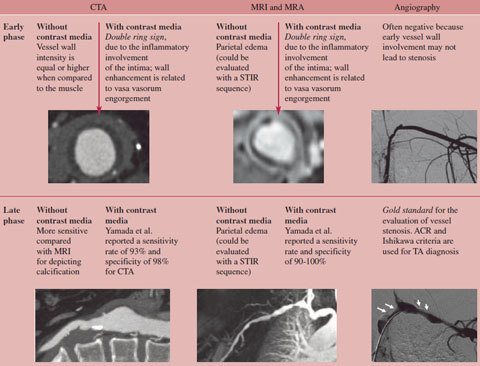

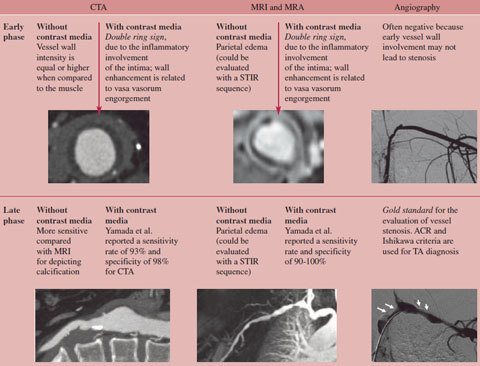

Table 16.3

Radiological findings of the early phase and late phase of TA

STIR, Short Tau Inversion Recovery.

According to EULAR/PRINTO/PRESS guidelines, we use Whole Body MRA (WB-MRA) for diagnosis and follow-up of TA, in particular in pediatric patients.

CTA could be employed as a diagnostic method in non-compliant patients and could be useful for studies of coronary arteries and pulmonary arteries.

Imaging and Reporting

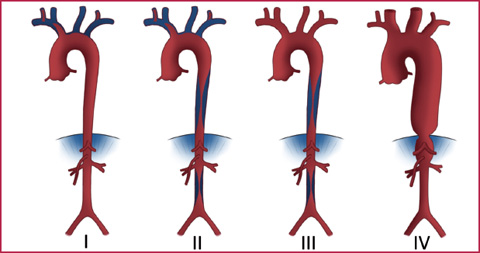

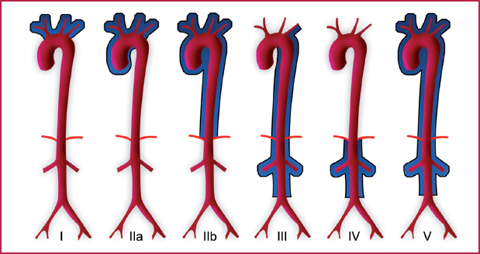

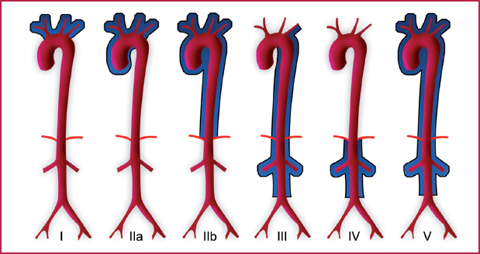

Typical vascular lesions have a specific siting. Numano et al. have proposed a classification of TA in 1996 with six disease subtypes (Fig. 16.3):

type I, supra-aortic vessels;

type IIa, ascending aorta and/or aortic arch (supra-aortic vessels may be involved);

type IIb, descending aorta with or without involvement of the ascending aorta and/or supra-aortic vessels;

type III, descending aorta, thoracic aorta and/or renal arteries (the ascending aorta, aortic arch and its branches are not involved);

type IV, abdominal aorta and/or renal arteries;

type V, generalized with more than one site.

Fig. 16.3

Numano’s classification of TA

Coronary and pulmonary artery involvement is reported as C (+) and P (+), respectively.

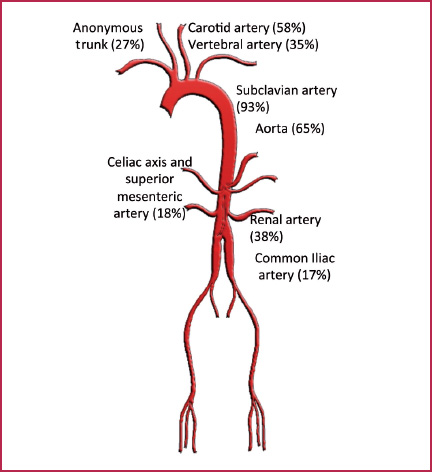

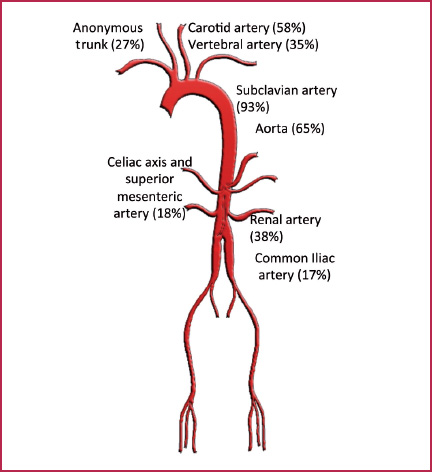

The angiographic study by Kerr et al. in 60 patients (Fig. 16.4) showed involvement of the subclavian artery (93%), aorta (65%), common carotid (58%), renal artery (38%), vertebral artery (35%), anonymous trunk (27%), celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery (18%), and iliac artery (17%).

Fig. 16.4

Kerr’s angiographic study

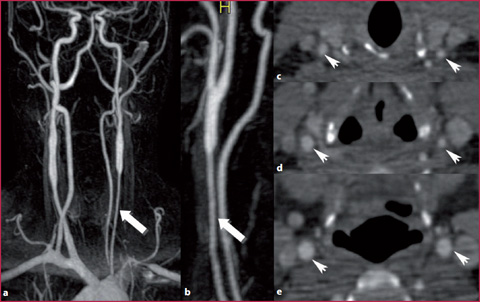

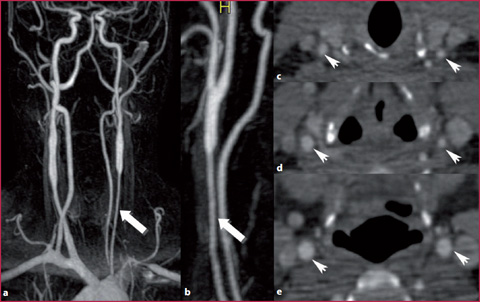

The typical MRI and MRA findings of TA are showed in Fig. 16.5.

Fig. 16.5

MRA of a 22-year-old female with TA. a Coronal MIP image shows bilateral carotid stenosis that is more evident on the left side (arrow). c,d CTA confirmed bilateral stenosis (arrow heads). e Normal carotid caliper close to the bifurcation (arrow heads)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree