Venous Stenosis in the Hemodialysis Patient: A Transplant Surgeon’s Perspective

The presentation of patients with acute renal failure, patients with the acute need for dialysis in the setting of chronic renal insufficiency, and those on chronic hemodialysis awaiting maturation of a permanent access all require the use of temporary dialysis catheters to perform their necessary hemodialysis therapy. These catheters have been an invaluable adjunct in maintaining the hemodialysis population. Their widespread use, however, has highlighted several important complications that limit their usefulness. Catheter malfunction related to thrombosis, although correctable through the use of urokinase, may result in delays in the patient’s dialysis schedule. Catheter-related sepsis may be reduced by the use of Dacron-cuffed Silastic catheters, but it remains a significant cause of early catheter removal. Infection of these catheters in the worst cases can lead to endocarditis or even epidural abscesses. From the standpoint of the transplant or vascular surgeon charged with creating long-term hemodialysis access, the most vexing complication of temporary dialysis catheters has been the development of central venous stenosis or occlusion.

Injury to the subclavian vein secondary to catheters inserted through this route may result in the potential loss of the ipsilateral limb for the formation of chronic dialysis access. The presence of subclavian venous stenosis or occlusion typically remains occult until a graft or fistula is created in that arm. Subsequently, massive edema in the arm, fistula dysfunction secondary to high recirculation with resultant poor clearance, or fistula or graft thrombosis in the context of the high venous pressure created by the poor outflow may ensue. Subclavian venous narrowing or obstruction may occur at the site of a venous valve or arise de novo, but investigators ascribe the vast majority of these lesions to the prior presence of subclavian venous catheters. Thus, prevention of subclavian venous lesions may be a more straightforward task than is their subsequent treatment or repair.

Etiology

Etiology

Stenoses or venous occlusions may occur at the site of subclavian insertion into the vein or, more proximally, within the brachiocephalic vein or at the junction of superior vena cava and the right atrium. Numerous factors associated with the use of central venous catheterization have been implicated in the possible etiology of catheter-related central venous stenosis. Intimal trauma secondary to catheter or vein movement during the cardiac cycle or ventilation may lead to scarring and fibrosis at the contact points of the catheter with the vein wall1 and may explain the occurrence of stenoses at sites proximal to the venous insertion. Infection of the vessel wall secondary to the propagation of bacteria along the subcutaneous path of the catheter also has been suggested as a potential cause of subclavian narrowing or occlusion.2 Symptoms related to central venous stenosis, following ipsilateral placement of an arteriovenous fistula or graft, may occur rapidly or develop months after fistula formation. Turbulence at a site of partial stenosis, created by catheter insertion, may provoke further fibrosis.3 Thus, catheter placement may initiate a process that is exacerbated by the high flow in the central veins induced by the fistula.

Internal Jugular Catheterization

Internal Jugular Catheterization

In light of the suggested possible etiologies of subclavian venous stenosis, prevention would appear to involve avoidance of subclavian catheterization and use of alternative routes. This point needs to be stressed with residents or intensivists who may be aiding in the care of the hemodialysis patient. Several investigators demonstrated a markedly reduced incidence of venous stenosis when the internal jugular vein is preferentially cannulated. Use of the jugular vein eliminates direct trauma to the wall of the subclavian vein. The right jugular vein in particular offers a relatively straight path into the superior vena cava and minimizes points of contact and trauma to the intimal lining. In a retrospective investigation of patients studied angiographically following insertion of temporary catheters through the subclavian route, Cimochowski et al1 demonstrated a 50% incidence of subclavian vein narrowing. None of the patients with internal jugular vein catheters developed venous stenosis. Schillinger et al4 confirmed these findings in a randomized prospective trial and demonstrated a 42% subclavian vein stenosis rate when percutaneous access was established through this vessel. This finding contrasted with a 10% incidence of stricture in the subclavian or brachiocephalic veins when the dialysis catheter was placed in the internal jugular vein. These studies highlight the ability to prevent narrowing or occlusion of the subclavian vein by preferentially using the internal jugular vein for temporary access placement, thus preserving venous outflow from the arms for graft or fistula construction.

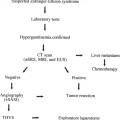

Therapy of Central Venous Stenosis or Obstruction

Therapy of Central Venous Stenosis or Obstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree