and Siddharth P. Jadhav2

(1)

Department of Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch Pediatric Radiology, Galveston, TX, USA

(2)

The Edward B. Singleton Department of Pediatric Radiology, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA

Abstract

This chapter deals with injuries of the wrist and hand. Various types of fractures and other injuries are presented. MR is discussed where it significantly adds to evaluation of these injuries.

Injuries of the Wrist

Evaluation of Fat Pads and Soft Tissues

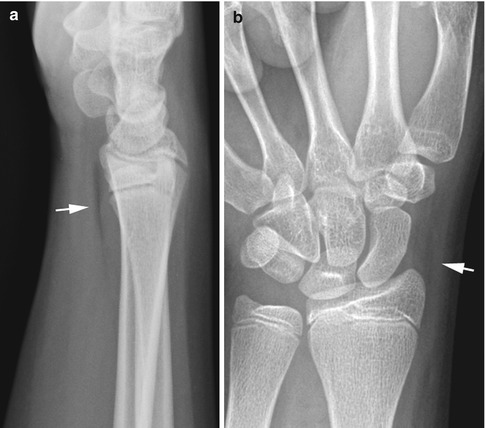

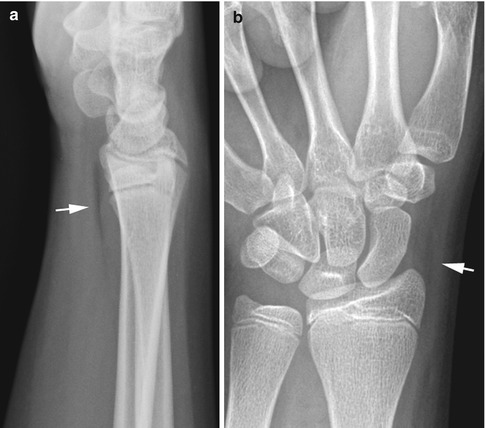

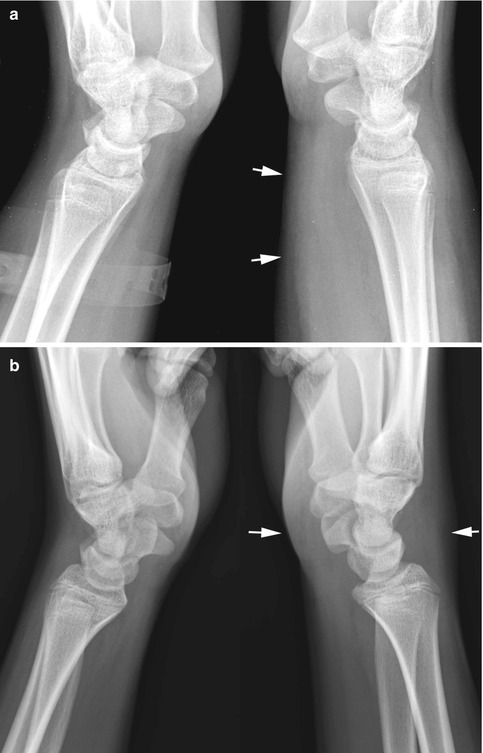

There are two fat pads around the wrist that can be utilized in the assessment of wrist injuries. The first is the pronator quadratus fat pad [1], and the second is the navicular fat pad [2]. The pronator quadratus fat pad is seen on lateral views of the wrist and lies along the pronator quadratus muscle (Fig. 7.1a). The navicular fat pad lies just medial to the scaphoid bone and is seen on anteroposterior views of the wrist (Fig. 7.1b). In young infants, this latter fat pad is not visualized with as much consistency as it is in older children. However, this is not so unfortunate because obliteration of the navicular fat pad is utilized primarily for the detection of navicular fractures, and these fractures are not particularly common in infants and young children. Distal radial and ulnar fractures, on the other hand, are quite common, and it is in this regard that displacement and obliteration of the pronator quadratus fat pad becomes most useful.

Fig. 7.1

Normal fat pads. (a) Note the position and configuration of the quadratus fat pad (arrow). (b) Navicular fat pad. This fat pad (arrow) lies adjacent to the scaphoid bone

Determining the Presence of Fluid in the Wrist Joint

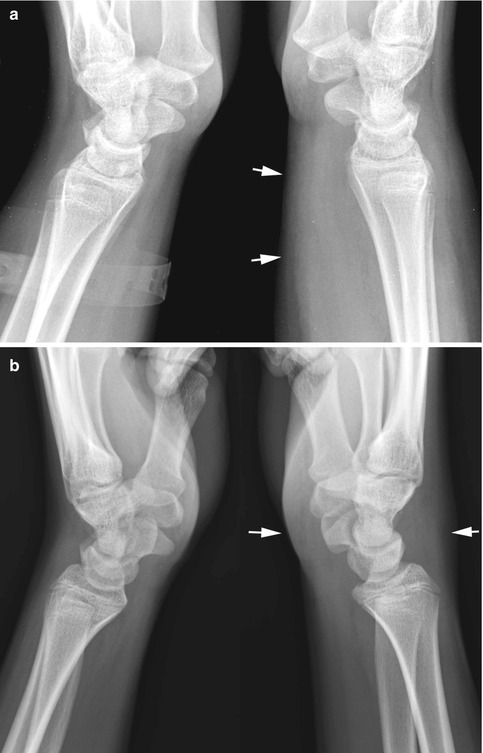

Determining the presence of fluid in the wrist joint is not possible with plain films and thus one must rely on soft tissue edema to focus ones attention on any possible underlying bony abnormality. In terms of swelling, if the problem is in the wrist proper, swelling will be most pronounced distal to the radial epiphyseal plate (Fig. 7.2c, d), but if the problem is in the distal radius/ulna, swelling is most pronounced proximal to the radial epiphyseal plate (Fig. 7.2a, b).

Fig. 7.2

Value of soft tissue swelling location. (a) In this patient most of the swelling is in the proximal wrist and distal forearm (arrows), proximal to the radial epiphyseal plate. With swelling in this area, one should look for fractures in the distal radius. In this regard there is a minimal angle buckle fracture over the dorsum of the distal wrist. (b) In this patient swelling is more distal, that is, in the wrist proper (arrows), and in such cases, one should look for fractures of the carpal bones, most often the scaphoid bone

Injuries of the Distal Radius and Ulna

Although a variety of overt transverse and oblique fractures commonly occur through the distal third of the radius and ulna, these fractures usually are not difficult to detect (Fig. 7.3). At the other end of the spectrum of distal radial and ulnar fractures are the cortical buckle or torus fractures [3]. Both standard buckle and angled buckle fracture are common, but these fractures often can be subtle on AP and oblique views. They are usually more clearly seen on lateral views of the wrist (Figs. 7.4 and 7.5). Indeed, the lateral view is the money view for wrist fractures of the distal radius and ulna, including the relatively uncommon childhood equivalent of the Smith’s fracture (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.3

Distal radius and ulna fractures. (a) Typical transverse overriding fractures of both the radius and ulna. (b) In this patient a direct blow to the ulna resulted in a greenstick fracture (arrow). (c) Galeazzi’s fracture. Note the fracture and angulation of the radius. The ulna is dislocated. (d) Lateral view demonstrating same findings

Fig. 7.4

Buckle (torus fractures): typical. (a) Note the typical impacted buckle fracture with outward bulging of the cortex (arrow). (b) Lateral view demonstrates similar findings (arrow). (c) In this patient cortical bulging is seen on both sides (arrows). (d) Very subtle buckle fracture (arrow)

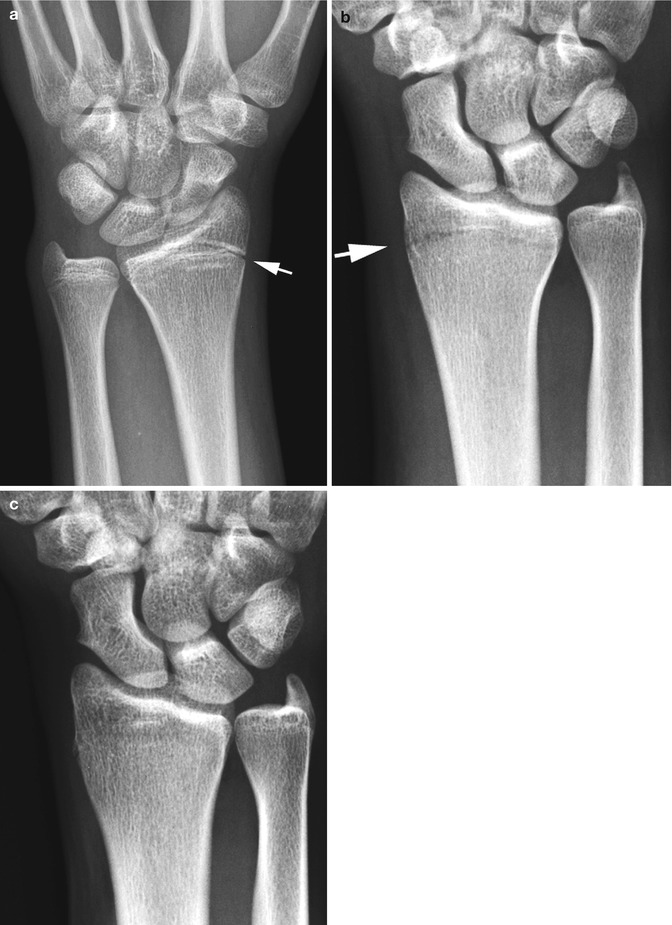

Fig. 7.5

Buckle (torus fractures): angled. (a) Note the angled buckle fracture (arrow) in the distal radius. (b) Normal side for comparison. Note the smooth configuration of the dorsal cortex of the radius. (c) Very minimal angled buckle fracture of the distal radius (arrow). (d) Normal side for comparison

Fig. 7.6

Angled buckle fracture: Smith’s fracture equivalent. Note the angled buckle fracture (arrow) through the distal ventral aspect of the radius. Compare with the normal other side

Epiphyseal/metaphyseal Salter–Harris fractures also are very common in the wrist, especially the distal radius. The most common of these are the Salter–Harris I and II fractures. Types III, IV, and V injuries are relatively uncommon. Salter–Harris type I injuries can be very subtle [4]. In most instances the injury results from falling on the outstretched extremity, and most often it is the distal radial epiphysis which is involved and displaced posteriorly (Fig. 7.7). These Salter injuries can occur even in older children where the epiphysis is basically closed (Fig. 7.8).

Fig. 7.7

Salter–Harris epiphyseal/metaphyseal fractures. (a) Salter–Harris I fracture. Note slight widening of the epiphyseal plate on the left (arrow). Compare with the normal right side. (b) On lateral view widening of the epiphyseal plate is again seen and there is slight posterior displacement of the distal radial epiphysis (arrow). (c) Normal side for comparison. Note the normal width of the epiphyseal plate and the position of the epiphysis. (d) Salter–Harris II equivalent fracture. The distal radial epiphysis is posteriorly displaced (arrow), and the epiphyseal plate is widened. The dorsal cortex of the radius is angled. With more force this fragment of bone would break off and become a classic Salter–Harris II fracture fragment

Fig. 7.8

Salter–Harris fracture: older children. (a) Note that the ulnar epiphysis is nearly closed. However, the distal radial epiphyseal plate is slightly open (arrow) and there is some adjacent sclerosis in the metaphysis. These findings are typical for a Salter–Harris I fracture in a patient where the epiphyses have basically closed. (b) Another patient with a very minimal Salter–Harris fracture (arrow) through the fused epiphyseal plate. Also note the fracture of the tip of the ulnar styloid process. Note that the ulnar epiphyseal plate is closed. (c) Normal side for comparison

Finally in terms of Salter–Harris fractures, it should be noted that chronic stress-induced epiphyseal/metaphyseal fractures of the distal radius and ulna can be seen in gymnasts and other young athletes who overuse the wrist [5–9]. These fractures appear as healing Salter–Harris I epiphyseal/metaphyseal fractures (Fig. 7.9). The problem is one of chronic, repetitive subclinical stress on the wrist and, hence, the gymnast wrist.

Fig. 7.9

Gymnast wrist. Note the widened epiphyseal line and sclerosis in the metaphysis (arrow). These findings are typical for a chronic Salter–Harris I fracture, that is, a gymnast wrist

Ulnar styloid fractures although appearing innocuous are very important. The reason for this is that they usually herald the presence of an associated significant radial fracture [10]. This occurs because the wrist is encircled by strong ligaments and muscles, and when rotation/impaction injuries occur, the forces involve both the radius and ulna. In terms of the ulna, it is the ulna styloid tip which is fractured and avulsed. If the associated radial fracture is obvious, there is no problem (Fig. 7.10a). However, in lesser cases only the ulnar styloid fracture is apparent on AP views (Fig. 7.10b). In such cases one should look for an almost always present distal radial fracture, either a buckle fracture or a Salter–Harris fracture (Fig. 7.10c). Isolated ulnar styloid fractures can be seen if direct blows to the styloid process are sustained [10].

Fig. 7.10

Ulnar styloid tip fractures: significance. (a) Note the ulnar styloid tip fracture (arrow) and an associated impaction fracture of the distal radius. (b) In this patient the ulnar styloid fracture is very subtle (arrow). In addition there is subtle irregularity of the trabeculae and slight bulging of the cortex in the distal radius (arrows). (c) On lateral view, an angled buckle fracture (arrow) of the distal radius is seen. D. Normal bifid ulnar styloid epiphysis (arrow)

Old, ununited styloid avulsion fractures may erroneously suggest the presence of a secondary ossification center. I have seen only one such secondary center in my career. Otherwise, the finding should represent an old, ununited fracture of the tip of the ulnar styloid. However, the normal ulnar epiphysis can be bipartite through its midpoint (Fig. 7.10d). In these cases there should be no confusion with a fracture for such fractures basically do not occur.

Injuries of the Carpal Bones

Fractures or dislocations of the carpal bones in infants and young children are uncommon. They are more common in the older child and adolescent, and of these, fractures of the scaphoid bone are most common [13]. The clinical findings in these fractures are similar to those seen in adults (i.e., acute tenderness in the anatomic snuff box), and the fractures result from falls on the outstretched extremity.

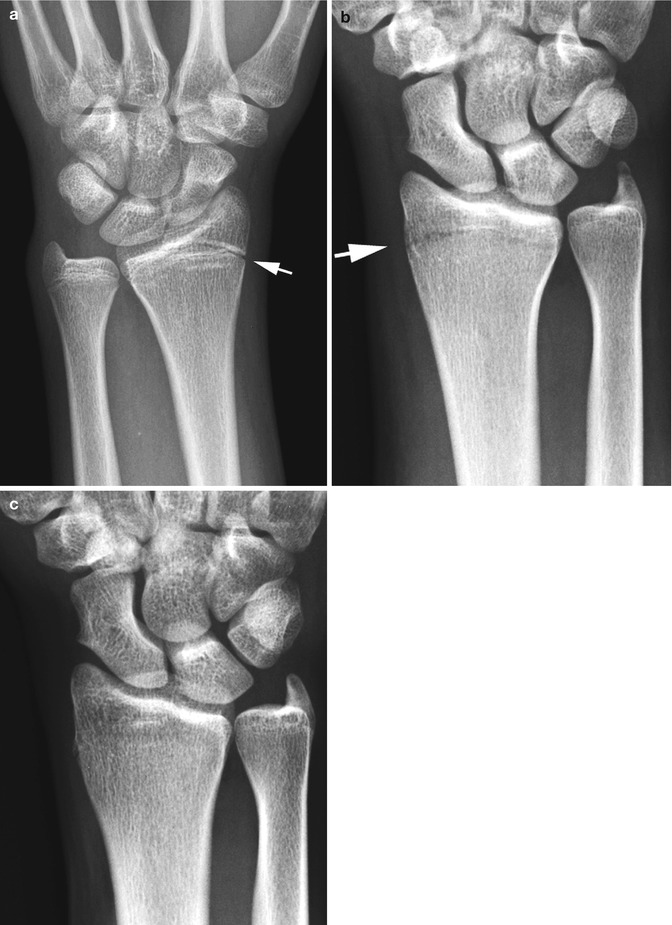

In terms of plain film imaging, this fracture can be suspected if there is juxta-navicular soft tissue swelling and/or obliteration of the adjacent navicular fat pad [1, 13]. If the fat pad is intact, it is highly unlikely that a scaphoid fracture is present. In the classic case of a transverse fracture, the findings are not difficult to detect (Fig. 7.11). However, in children an impacted buckle/stress fracture of the scaphoid bone is probably just as common or even more common than the transverse fracture [14–16]. The findings often are very subtle, and comparative views are critical (Fig. 7.12). In puzzling cases, if a question about a fracture is still present, one can resort to nuclear scintigraphy [17] or MR imaging [18–20].

Fig. 7.11

Scaphoid fracture. Note a typical transverse fracture (arrow) through the scaphoid bone

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree