Male Genital Tract

Sonography is the imaging examination of choice for the study of most scrotal pathology (1,2,3,4). Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used in delineating the extent of primary scrotal tumors (5,6). They also are the studies of choice for the diagnosis of prostate and seminal vesicle pathology.

SCROTAL ANATOMY

Each hemiscrotum contains the testis, epididymis, and the intrascrotal part of the spermatic cord. The testis and epididymis are covered by the tunica vaginalis, which is derived from the processus vaginalis of the peritoneum (Fig. 11.1). The tunica consists of an outer parietal and inner visceral layer, separated by 1 to 2 mL of fluid. The parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis lines the wall of the scrotum and attaches to the fascial covering of the testis. The visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis covers the fibrous capsule of the testis, called the tunica albuginea, the epididymis, and the lower portion of the spermatic cord. Normally, the tunica vaginalis does not cover the posterior aspects of the testis and epididymis, which are the sites of attachment to the scrotum. The tunica albuginea gives rise to small septa, which invaginate into the testis to form a vertical septum, called the mediastinum testis. The mediastinum testis provides support for the veins, arteries, and ducts as they enter and exit the testis.

The epididymis lies along the posterolateral aspect of the testis. The head is the largest portion of the epididymis and is located over the superior pole of the testis. It continues into the epididymal body and then tapers into the epididymal tail, which lies along the inferior aspect of the testis. The tail connects to the ductus deferens, which ascends to the spermatic cord and empties into the seminal vesicles.

The spermatic cord contains various arteries, the pampiniform plexus of veins, nerves and lymphatics, as well as the ductus deferens. The testicular (internal spermatic) artery, which provides the main blood supply for the testis, arises from the abdominal aorta. It courses along the posterior surface of the testis where it penetrates the tunica albuginea to form capsular arteries, which run just beneath the tunica albuginea (Fig. 11.2). The capsular arteries give rise to centripetal arteries, which enter the parenchyma and course toward the mediastinum. As they approach the mediastinum, the centripetal arteries give rise to recurrent branches that run back away from the mediastinum.

The testicular (internal spermatic) artery provides the main blood supply for the testis.

The deferential artery, a branch of the vesicular artery, and the cremasteric artery, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery, provide the arterial supply to the epididymis, ductus deferens, and peritesticular tissue. The deferential and cremasteric arteries converge with

the testicular artery at the mediastinum testis. Although there are anastomoses between three arteries, the testicular artery is responsible for most of the blood supply to the testis. Branches of the pudendal artery supply the scrotum itself.

the testicular artery at the mediastinum testis. Although there are anastomoses between three arteries, the testicular artery is responsible for most of the blood supply to the testis. Branches of the pudendal artery supply the scrotum itself.

Figure 11.1 Normal anatomy of the scrotum. (From Krone KD, Carroll BA. Scrotal ultrasound. Radiol Clin North Am 1985;23:121-139, with permission.) |

The pampiniform plexus, the draining veins of the testis, empty into the testicular (internal spermatic) veins. The right testicular vein empties into the inferior vena cava, and the left vein drains into the left renal vein.

There are three major testicular appendages: (a) the appendix testis, attached to the upper pole of the testis; (b) the appendix epididymis, found on the head of the epididymis; and (c) the vas aberrans, located at the junction of the body and tail of the epididymis (Fig. 11.3).

There are three major testicular appendages: appendix testis, appendix epididymis, vas aberrans.

The neonatal testis measures 1.5 cm in length and 1.0 cm in width. During the first 3 months of life, testicular length increases to 2.0 cm and width to 1.2 cm due to a normal physiologic increase in testosterone levels. The testes then maintain a relatively constant size until the patient is about 6 years of age, when they again enlarge. The postpubescent

testis measures 3 to 5 cm in length and 2 to 3 cm in both anteroposterior diameter and in width. Testicular volume ranges from <1.0 cm3 in neonates to 30 cm3 in postpubertal adolescents.

testis measures 3 to 5 cm in length and 2 to 3 cm in both anteroposterior diameter and in width. Testicular volume ranges from <1.0 cm3 in neonates to 30 cm3 in postpubertal adolescents.

SONOGRAPHIC ANATOMY

On gray-scale sonography, the normal infant testis is ovoid and has a uniform low- to medium-level echogenicity. Testicular echogenicity increases from age 8 years until puberty, at which time the testis appears as a homogeneous structure of medium echogenicity. In adolescents, the mediastinum testis is often seen as a linear echogenic structure along the superior-inferior axis of the testis (Fig. 11.4). The tunica albuginea may be seen as a thin echogenic line around the testis. The epididymal head is triangular in shape and has an echogenicity equal to or slightly greater than that of the testis (Fig. 11.5). The epididymal body has an echogenicity equal to or slightly less than that of the testis. The epididymal tail is not usually seen on sonography.

The normal infant testis is ovoid and has a uniform low- to medium-level echogenicity.

With color Doppler imaging, centripetal arteries are identifiable in 60% to 85% of prepubertal testes and in virtually all postpubertal testes (Fig. 11.6) (7,8,9). The recurrent rami arteries are usually too small to be identified in young children, although they may be seen in adolescents. Pulsed Doppler imaging of the testicular arteries shows low-resistance waveforms with high levels of diastolic flow throughout the cardiac cycle. In contrast, the arteries at the periphery of the testis have a high-resistance waveform with low diastolic flow.

With color Doppler imaging, centripetal arteries are identifiable in virtually all postpubertal testes.

With color Doppler technology, the normal prepubertal epididymis shows minimal or no detectable flow. The normal postpubertal epididymis more often shows flow, which is usually minimal in amount. The detection of moderate or marked vascularity should be considered abnormal.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

ANOMALIES OF NUMBER, SIZE, AND POSITION

Bilateral testicular absence or anorchidism occurs in 1 in 20,000 male newborns. Unilateral testicular absence or monorchidism, occurs in 1 in 5,000 boys and is usually left sided. Polyorchidism or testicular duplication is an anomaly characterized by multiple testes on one side of the scrotum. The testes usually share a common epididymis, vas deferens, and tunica albuginea, although each testis may have a separate epididymis and vas deferens. Polyorchidism usually presents as an asymptomatic scrotal mass, but occasionally it can present with pain due to torsion. Polyorchid testes are homogenous, have medium level echoes, and are smaller than the normal contralateral testis.

Polyorchidism or testicular duplication characterized by multiple testes.

Transverse testicular ectopia is an anomaly in which both testes are located in the same hemiscrotum. Patients present with a nonpalpable testis and a contralateral scrotal mass. Associated anomalies include hypospadias, seminal vesicle cysts, renal dysplasia, ureteropelvic obstruction, and ipsilateral inguinal hernia.

CYSTIC DYSPLASIA OF THE TESTES

Cystic dysplasia of the testis, also known as tubular ectasia of the rete testis, is a condition characterized by cystic dilatation of the rete testis and the efferent ducts (10,11). Patients usually present with painless scrotal enlargement. Ipsilateral renal agenesis, multicystic

dysplastic kidney, and renal dysplasia are common associated findings. Sonography shows multiple small cystic or tubular structures in the region of the mediastinum testis.

dysplastic kidney, and renal dysplasia are common associated findings. Sonography shows multiple small cystic or tubular structures in the region of the mediastinum testis.

Figure 11.6 Normal intratesticular vascular anatomy. Longitudinal image of a postpubertal patient shows capsular arteries (arrows) and multiple centripetal arteries. (See color plate.) |

CRYPTORCHIDISM

Undescended testis or cryptorchidism is found in approximately 30% of premature male infants weighing under 2,500 g and in 3% to 4% of term infants. Testicular descent continues in the postnatal period, so that at the end of the first year of life, <1% of infants have true cryptorchidism. Undescended testes can be found anywhere from the renal hilum to the inguinal canal. Approximately 80% to 90% of undescended testes are found at the level of the inguinal canal or just proximal to the internal inguinal ring, and the remaining 10% to 20% are located in the abdomen. Rarely, the testis is found in the perineum or at the base of the penis. Cryptorchidism is bilateral in 10% to 30% of patients, and associated urologic abnormalities are found in 20% of affected boys (12).

80% to 90% of undescended testes are found at the level of the inguinal canal or just proximal to the internal inguinal ring.

The major complications of undescended testis are malignant degeneration and infertility. Orchiopexy is the treatment of choice, although the increased risk of malignancy and fertility problems persists even after successful surgery. Preoperative localization of a nonpalpable, undescended testis by radiologic examination is helpful in directing the surgical approach and shortening anesthesia time. Because most undescended testes lie within the inguinal canal, sonography is the examination of choice to detect a nonpalpable testis (12). Laparoscopic techniques have largely supplanted MRI for the evaluation of testes located above the inguinal ring.

The major complications of undescended testis are malignant degeneration and infertility.

The sonographic appearance of the cryptorchid testis is similar to that of the normal testis lying within the scrotal sac, although the undescended testis tends to be smaller and less echogenic than the normally located testis (Fig. 11.7). Inguinal lymph nodes can mimic an undescended testis. Differentiation from a cryptorchid testis is facilitated if a mediastinum testis can be identified.

The undescended testis tends to be smaller and less echogenic than the normally located testis.

After surgical repair, the undescended testis usually remains small and hypoechoic compared with the normal testis.

SCROTAL TUMORS

The role of imaging in the evaluation of scrotal masses is to determine whether the mass is intratesticular or extratesticular (13,14,15). This is important because the vast majority of intratesticular lesions are malignant, whereas most extratesticular lesions are benign.

Most intratesticular tumors are malignant, whereas most extratesticular tumors are benign.

PRIMARY TESTICULAR NEOPLASMS

Germ-Cell Tumors

Primary testicular neoplasms account for about 1% of all tumors in boys. Approximately 90% of testicular tumors are germ-cell neoplasms and most of these are malignant (16,17). The yolk sac tumor is the most common malignant germ-cell tumor in prepubertal boys. Median patient age is 2 years. The embryonal carcinoma is the most common tumor in pubescent boys, followed in frequency by teratocarcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and seminoma. Teratoma is the most common benign testicular tumor. It accounts for 5% to 10% of germ-cell tumors and is usually found in children less than 4 years of age. Patients with testicular tumors usually present with painless scrotal or testicular enlargement. A small number will present with acute pain as a result of torsion or hemorrhage into the tumor or with symptoms from metastatic disease.

Approximately 90% of testicular tumors are germ-cell neoplasms and most of these are malignant.

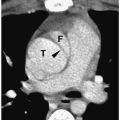

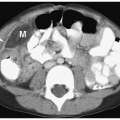

Excluding the seminomas, the majority of germ-cell tumors are heterogeneous and either hypo- or hyperechoic relative to normal testis (Figs. 11.8, 11.9, and 11.10). By comparison, seminomas are usually uniformly hypoechoic masses (Fig. 11.11). Scrotal skin thickening is rarely associated with testicular tumors. Findings of intrascrotal extension include irregularity of the tunica albuginea and reactive hydroceles. Sites of distant metastases include retroperitoneal lymph nodes (characteristically at the level of the renal hila), lungs, liver, brain, and bone. Tumors under 1.5 cm in diameter are often avascular or hypovascular, whereas larger tumors are often hypervascular on Doppler imaging (18).

MRI is usually not needed for the diagnosis of tumor, but it can be useful if sonography cannot show the full extent of a lesion. Similar to most other tumors, malignant testicular

tumors are isointense to normal testis on T1-weighted images and hyperintense to normal testicular tissue on T2-weighted images. Larger tumors tend to be heterogeneous.

tumors are isointense to normal testis on T1-weighted images and hyperintense to normal testicular tissue on T2-weighted images. Larger tumors tend to be heterogeneous.

MRI can be useful if sonography cannot show the full extent of a testicular tumor.

Figure 11.9 Embryonal cell carcinoma in a 16-year-old boy. Longitudinal sonogram shows a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass (arrowheads) within the upper pole of the right testis (T). |

Stromal Tumors

Stromal tumors account for approximately 10% of testicular neoplasms in children. These are usually of Sertoli or Leydig cell origin and both are nearly always benign (15,17,19). Sertoli cell tumors usually appear as painless masses in the first year of life. However, they may produce estrogens that result in precocious puberty or gynecomastia. Leydig cell tumors usually occur in patients between 3 and 6 years of age. These tumors produce estrogens or testosterones with resultant gynecomastia or virilization. The sonographic appearance of both stromal tumors is a well-defined hypoechoic mass (Fig. 11.12). Cystic spaces resulting from hemorrhage or necrosis may be seen in larger tumors.

Stromal tumors account for 10% of testicular neoplasms and are nearly always benign.

Miscellaneous Testicular Masses

Gonadoblastomas are rare mesenchymal tumors and are nearly always found in phenotypic females with streak gonads or testes and a male karyotype (16). Most are small and diagnosed only at the time of surgery to remove intraabdominal dysplastic gonads. If seen at sonography, they are usually solid and hypoechoic, although occasionally cystic spaces can be observed (20). Gonadoblastoma is considered benign, but malignant germ-cell elements have occasionally been found in the tumor.

Other benign intratesticular masses include lipoma, hemangioma, neurofibroma, fibroma epidermoids, and cysts. On sonography, benign lesions are usually solid and hypoechoic, but they can be complex or hyperechoic masses.

Other benign intratesticular masses include lipoma, hemangioma, neurofibroma, fibroma epidermoids, and cysts.

Figure 11.12 Leydig cell tumor. Longitudinal view of the testis demonstrates a focal hypoechoic tumor (T). |

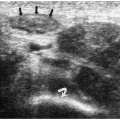

Non-neoplastic lesions that resemble benign solid neoplasms include Leydig cell hyperplasia, adrenal rests, epidermoids, hematomas, and focal orchitis. Adrenal rests arise from fetal adrenal cortical cells that migrate coincidental with the gonadal tissue in utero. These cells can form tumor-like masses in response to increased levels of adrenocortical hormones. At sonography, adrenal rests appear as round hypoechoic, nodular masses, most commonly located near the mediastinum testis (Fig. 11.13) (21). They are often multiple and bilateral.

Adrenal rests can form tumor-like masses in response to increased levels of adrenocortical hormones.

Epidermoid cysts are well circumscribed and hypoechoic masses. They may have internal echoes or an “onion-skin” lamellated appearance (Fig. 11.14) (22). On MRI, they have a similar ringed appearance with a low-signal intensity capsule.

Epidermoid cysts are well circumscribed and may have internal echoes or an “onion-skin” lamellated appearance.

SECONDARY TESTICULAR NEOPLASMS

Leukemia, lymphoma, and metastases are causes of secondary testicular neoplasms (23). Leukemic infiltrates are rarely clinically symptomatic and most are incidental findings at imaging, biopsy, or autopsy. Leukemic and lymphomatous infiltration can produce focal hypoechoic masses or enlarged, homogeneous, hypoechoic testes, (Figs. 11.15 and 11.16). Color Doppler imaging shows hyperemia.

Leukemia, lymphoma, and metastases are causes of secondary testicular neoplasms.

Primary neoplasms that can metastasize to the testis include Wilms’ tumor, neuroblastoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, sinus histiocytosis, retinoblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma (15,17). Metastases can appear as a focal hypoechoic mass, a diffusely enlarged testis, or extratesticular mass. The tumors are usually hypervascular on color Doppler imaging.

Figure 11.13 Adrenal rest. Longitudinal sonogram in an adolescent boy with congenital adrenal hyperplasia shows a well-defined hypoechoic mass (arrowheads) within the mediastinum testis. |

Figure 11.14 Epidermoid cysts. Longitudinal sonogram in a 13-year-old boy showing a well-defined hypoechoic mass (cursors) with internal lamellation. |

Figure 11.16 Leukemia.A. Longitudinal sonogram in a 10-year-old boy acute lymphoblastic leukemia and scrotal swelling shows an enlarged left testis (cursors) with mildly heterogeneous echotexture. B. Color Doppler image showing increased testicular blood flow with irregular appearing vessels. (See color plate.) |

PARATESTICULAR TUMORS

Malignant Lesions

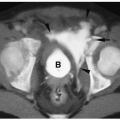

Paratesticular tumors usually involve the epididymis or spermatic cord. Most are benign, but about 30% are malignant, with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma being the most common tumor (1,16,19). Other malignant paratesticular tumors include metastatic neuroblastoma, lymphoma, leiomyosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma (24). Malignant paratesticular tumors tend to appear as well-defined homogenous or heterogenous solid masses with an echogenicity that is equal to or slightly less than that of the testis (Fig. 11.17).

About 30% of paratesticular tumors are malignant, with embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma being the most common.