Spleen and Peritoneal Cavity

SPLEEN

The spleen is rarely the site of primary disease, but it is often secondarily involved by infectious, inflammatory and neoplastic conditions originating at other sites. Sonography provides an easy means of screening for splenic abnormalities, and it is often the initial imaging examination performed to evaluate suspected splenic pathology. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to characterize further an abnormality and determine its extent (1,2,3,4,5,6). Radionuclide imaging currently has little role in the evaluation of splenic disease, but in equivocal cases, imaging with heat-damaged tagged red blood cells can be used to confirm the presence of splenic tissue.

NORMAL VARIANTS AND CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Wandering Spleen

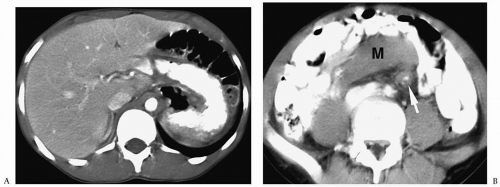

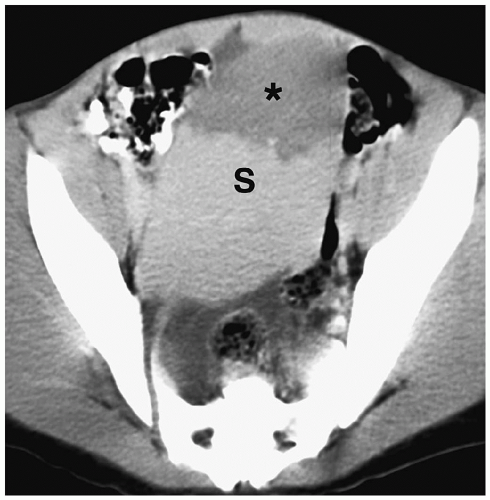

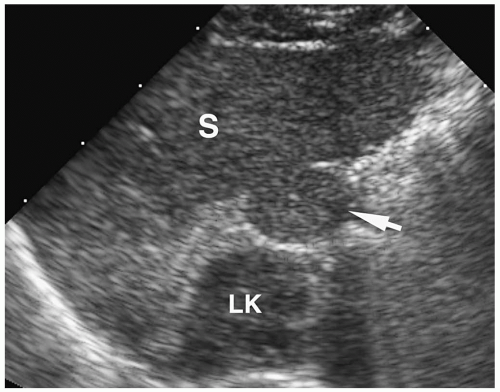

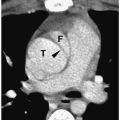

The wandering spleen is a disorder characterized by laxity of the suspensory splenic ligaments, which allows the spleen to lie in an ectopic location. Clinical findings range from an asymptomatic abdominal mass or intermittent abdominal pain (secondary to torsion and detorsion of the splenic pedicle) to an acute surgical abdomen (consequent to torsion of the splenic pedicle and vascular compromise). The imaging findings consist of absence of splenic tissue in the left upper quadrant and a mass elsewhere in the abdomen with a shape and architecture similar to normal spleen (Fig. 6.1) (7,8). The echotexture, attenuation, and signal intensity are similar to normal spleen. Findings of ascites, a twisted splenic pedicle, and a whorled appearance of the pancreatic tail and supporting fat indicate superimposed torsion. A focal hypoechoic lesion on sonography or nonenhancing lesion on CT suggests associated infarction (Fig. 6.2).

The wandering spleen is characterized by laxity of the suspensory splenic ligaments.

Accessory Spleens

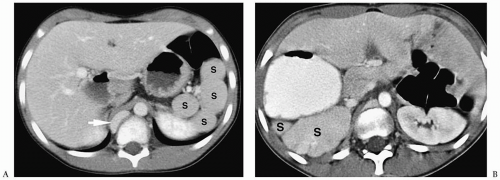

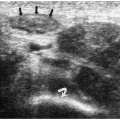

Accessory spleens are a common anatomic variant. They usually are clinically insignificant, except in patients who have had prior splenectomies for hematologic diseases. In these patients, the accessory splenic tissue can hypertrophy, resulting in recurrent hypersplenism. Most accessory spleens are located near the splenic hilum, but they also may be found along the splenic vessels or in the pancreatic tail. They are generally single, but about 10% are

multiple. Accessory spleens are usually smooth, round, or ovoid in shape and 2 to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 6.3). They tend to have an echotexture, attenuation, and signal intensity similar to normal spleen.

multiple. Accessory spleens are usually smooth, round, or ovoid in shape and 2 to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 6.3). They tend to have an echotexture, attenuation, and signal intensity similar to normal spleen.

Accessory spleens are a common anatomic variant.

Most accessory spleens are located near the splenic hilum.

Splenosis

Splenosis is the result of splenic rupture secondary to trauma or surgery with subsequent autotransplantation of splenic tissue. The peritoneal cavity is the most common site of splenosis, but splenic tissue can be found elsewhere in the abdomen or chest. On imaging studies, the splenic nodules in splenosis are round masses that are indistinguishable from accessory spleens. The masses in splenosis are distributed throughout the peritoneum and

the retroperitoneum, whereas accessory spleens are usually found in the left side of the abdomen near the splenic hilum.

the retroperitoneum, whereas accessory spleens are usually found in the left side of the abdomen near the splenic hilum.

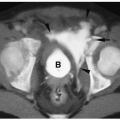

Polysplenia and Asplenia

Polysplenia and asplenia are both associated with cardiac and pulmonary abnormalities along with visceral heterotaxy (9). Polysplenia is characterized by multiple splenic nodules, which can be located in the right or left upper quadrants (Fig. 6.4). Associated abdominal anomalies include a transverse liver, interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygous continuation, short pancreas, abnormal rotation of the bowel, and renal agenesis or hypoplasia. Thoracic anomalies include bilateral left lungs, partial anomalous pulmonary venous return, and cardiac anomalies, including atrial and ventricular septal defects, transposition of the great vessels, and pulmonary stenosis or atresia.

Polysplenia and asplenia are associated with cardiac and pulmonary abnormalities and visceral heterotaxy.

Asplenia is characterized by absence of splenic tissue. Associated abdominal anomalies include total or partial sinus inversus, intestinal malrotation, and renal anomalies. Thoracic anomalies include bilateral morphologic right lungs and complex cyanotic heart lesions, including single ventricle, transposition of the great vessels, and total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage.

SPLENOMEGALY

The diagnosis of splenomegaly can usually be made clinically, but sonography, CT, and MRI can confirm the presence of an enlarged spleen and exclude other abdominal masses. Splenomegaly in children is usually the result of infectious processes, often Epstein-Barr virus infection and cat-scratch disease, the hemoglobinopathies, and hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma. Less common causes of splenic enlargement include vascular congestion, usually associated with portal hypertension, portal vein thrombosis or right heart failure, and infiltrative disorders such as Gaucher disease and Niemann-Pick disease. Massive splenomegaly is obvious on imaging studies, and measurements generally are not required for diagnosis (Fig. 6.5). Measurement of splenic length can be helpful when splenic enlargement is mild.

Splenomegaly is usually the result of infectious processes, the hemoglobinopathies, and hematologic malignancies.

SPLENIC CYSTS

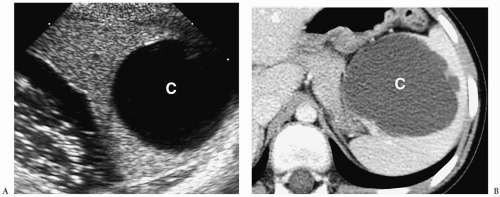

There are two major types of non-neoplastic cysts: primary or true cysts, which are lined by epithelium, and secondary or pseudocysts, which lack an epithelial lining. Primary cysts are usually congenital epidermoid cysts. Secondary cysts are most often the result of prior trauma or infection. Symptoms occur when the cysts are large and cause pressure on adjacent organs.

Congenital, parasitic, and post-traumatic cysts have similar appearances on sonography, CT, and MRI (10). They can be solitary or multiple and typically are well-circumscribed, spherical masses with smooth walls. On sonography, they are anechoic, and on CT, they have an attenuation value equal to or slightly greater than that of water (Fig. 6.6). On MRI, they are hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed images. Cysts show no central or rim enhancement after the administration of iodinated contrast or gadolinium. The echogenicity, attenuation value, and T1-weighted signal intensity increase when the fluid is hemorrhagic or proteinaceous. The diagnosis of echinococcal cyst should be suspected if daughter cysts are present within a large cystic

lesion or if cystic lesions are observed in other organs. Rim calcification may be noted in post-traumatic and parasitic cysts.

lesion or if cystic lesions are observed in other organs. Rim calcification may be noted in post-traumatic and parasitic cysts.

Congenital, parasitic, and post-traumatic cysts have similar imaging appearances.

The differential diagnostic considerations of a cystic splenic lesion include abscess, hematoma, and cystic neoplasm. When clinical or laboratory data are inconclusive for a specific diagnosis, fine-needle aspiration of the cyst contents can be helpful for diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis of a splenic cyst includes abscess, hematoma, and cystic neoplasm.

BENIGN SPLENIC MASSES

Most splenic tumors in childhood are benign and include hemangioma, lymphangioma, and hamartoma. Patients generally are asymptomatic, and the lesions are discovered incidentally, either as a palpable mass on physical examination or as an incidental finding on an imaging examination performed for other indications. Symptoms result when the lesions are large and compress adjacent organs.

Most splenic tumors in childhood are benign.

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are composed of vascular channels lined by a single endothelial layer and filled with red blood cells. They may be an isolated lesion or part of a syndrome, including Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber (characterized by capillary port-wine stains, varicosities, hypoplastic lymphatics, and lymphangiomas) and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (characterized by prenatal and postnatal overgrowth, macroglossia, anterior abdominal wall defects, and hemihypertrophy).

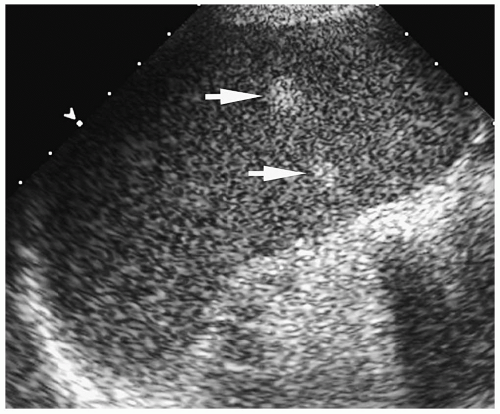

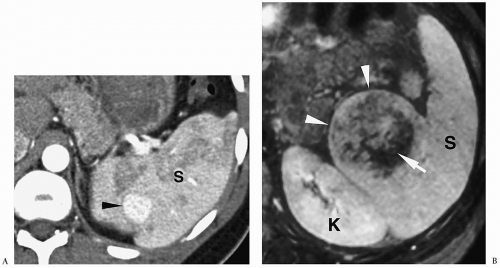

The imaging appearance of hemangioma in the spleen is similar to that in the liver. The lesions are either hypoechoic or hyperechoic relative to normal splenic parenchyma on sonography (Fig. 6.7), hypoattenuating on precontrast CT, hypointense on T1-weighted images, and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed images (11). After administration of iodinated contrast or gadolinium, hemangiomas typically show centripetal enhancement with progressive central fill-in. Small lesions may show early uniform fill-in without centripetal opacification, whereas very large lesions may demonstrate persistent central hypoattenuation or hypointensity due to areas of fibrosis or thrombosis (Fig. 6.8). Peripheral or central calcifications can be seen in some cases.

Hemangiomas show centripetal enhancement with progressive central fill-in.

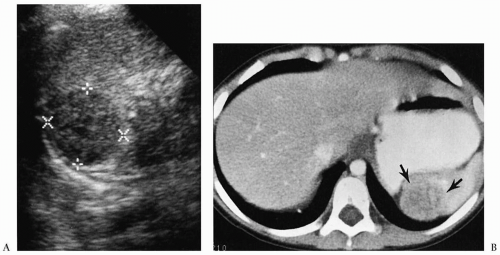

Lymphangioma

Lymphangiomas are congenital malformations of the lymphatic system (12) and may be solitary or multiple (lymphangiomatosis). On all imaging studies, they appear as multilocular masses. The fluid-filled locules are hypoechoic or anechoic on sonography, hypoattenuating on CT, hypointense on T1-weighted images, and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed images (Fig. 6.9). After administration of iodinated contrast or gadolinium, the cystic areas do not enhance, whereas the septa may show some enhancement.

Splenic lymphangiomas appear as multilocular masses.

Hamartoma

Splenic hamartomas are benign, solid lesions consisting of an admixture of normal splenic elements and disorganized congested splenic sinuses (red pulp). They have been associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and tuberous sclerosis. Relative to normal splenic tissue, hamartomas appear hypoechoic on sonography, hypo- or isoattenuating on precontrast CT scans, isointense on T1-weighted image, and hyperintense on T2-weighted and fat-suppressed images. They show mild to moderate, heterogeneous enhancement after intravenous contrast or gadolinium administration (Fig. 6.10).

Splenic hamartomas are benign, solid lesions.

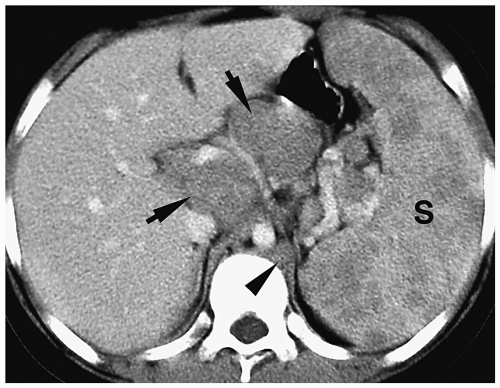

Figure 6.11 Hodgkin lymphoma. Contrast-enhanced CT shows splenomegaly (S) with multiple low-attenuation masses. Also noted is mesenteric (arrows) and retrocrural (arrowhead) adenopathy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|