Esophagus and Gastrointestinal Tract

Plain radiographs are still the study of choice to evaluate suspected gastrointestinal (GI) obstruction. Contrast studies remain the imaging tool of choice for confirming the presence and site of obstruction when plain radiographs are equivocal. Contrast examinations also are useful in evaluating patients with suspected esophageal disorders, infectious and inflammatory bowel diseases, and malabsorptive conditions. Ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) are most valuable for imaging patients with acute abdominal pain, gastrointestinal masses, and abscesses and are also useful to evaluate extraluminal extent of inflammatory bowel diseases.

CONGENITAL (NEONATAL) OBSTRUCTION

ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA

Esophageal atresia is the result of error in differentiation of the esophagus from the trachea. It occurs at the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the esophagus. Five types of esophageal atresia have been recognized, depending on the presence or absence of a fistula. The most common type is proximal atresia with a distal fistula to the trachea (80% to 90% of cases). A smaller number of patients have atresia without a fistula (10%), tracheoesophageal fistula (H-type fistula) without atresia (5%), esophageal atresia with a proximal fistula (1%), and esophageal atresia with both proximal and distal fistulas (1% to 2%) (1,2).

The most common type of esophageal atresia is proximal atresia with a distal fistula to the trachea.

Patients with esophageal atresia present at birth with excessive salivation or coughing and choking during attempts to feed. Attempts to pass a nasogastric tube are unsuccessful. Other anomalies are common, and the constellation of associated anomalies has been given the acronym VACTERL (V, vertebral defects; A, anal atresia; C, cardiac anomalies; T, tracheoesophageal atresia: R, radial and renal dysplasia; and L, limb anomalies. Duodenal atresia is another common anomaly).

The constellation of esophageal atresia and associated anomalies has been given the acronym VACTERL.

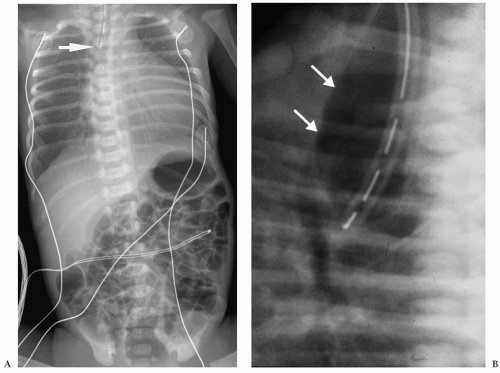

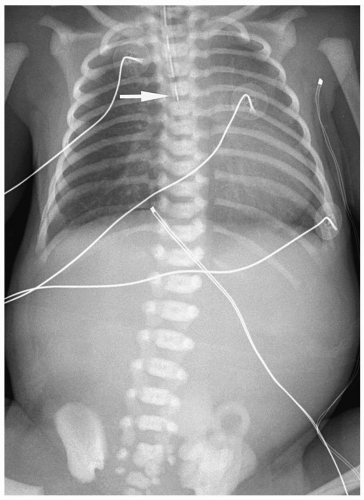

Plain radiographs characteristically show a nasogastric tube curled in an air-filled, dilated proximal esophageal pouch (Fig. 7.1). The presence of air in the stomach implies

the presence of a distal fistula or less likely proximal and distal fistulas. The absence of gastrointestinal air implies the absence of gastrointestinal communication (Fig. 7.2). Plain radiographs alone usually suffice for the diagnosis, and a contrast examination of the esophagus is not warranted.

the presence of a distal fistula or less likely proximal and distal fistulas. The absence of gastrointestinal air implies the absence of gastrointestinal communication (Fig. 7.2). Plain radiographs alone usually suffice for the diagnosis, and a contrast examination of the esophagus is not warranted.

Plain radiographs show a nasogastric tube curled in the esophageal pouch.

Figure 7.2 Esophageal atresia without distal fistula. An enteric tube is present in the upper esophageal pouch (arrow). There is no gas in the abdomen. |

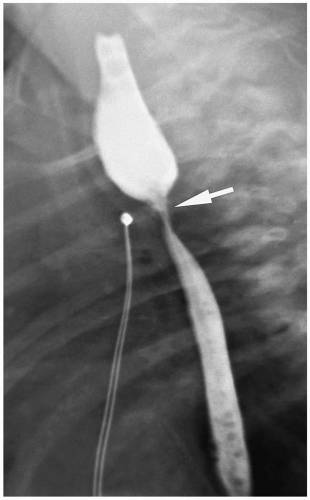

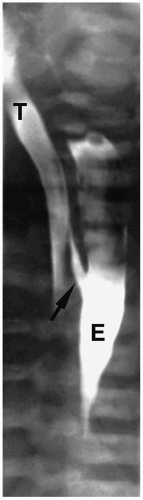

Figure 7.3 H-type fistula. A 21-day-old girl with coughing and cyanosis during feeding. The fistula (arrow) at the level of T1 passes obliquely upward from the esophagus (E) to the trachea (T). |

Patients with H-type fistulas without associated atresia differ from those with esophageal atresia. Most patients present in the first month of life with coughing and choking during feeding and recurrent pneumonias. Plain radiographs typically show an infiltrate, particularly in the right upper lobe. Contrast examinations are indicated to establish the diagnosis. The fistulas are usually small, and most have a cephalad course from the proximal esophagus to the trachea (Fig. 7.3).

Esophageal atresia is treated with an end-to-end anastomosis of the proximal and distal esophageal segments. Barium examination after repair typically demonstrates slight narrowing at the level of the anastomosis and esophageal dysmotility. The primary peristaltic wave breaks up just above the site of the anastomosis, and barium is transported across the anastomosis by a combination of gravity and propulsive action of the upper esophagus. There is an increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux in children who have undergone repair of esophageal atresia. Complications of repair are recurrent fistula, anastomotic

stricture (Fig. 7.4), and aspiration pneumonia. The latter is the result of esophageal dysfunction and of gastroesophageal reflux.

stricture (Fig. 7.4), and aspiration pneumonia. The latter is the result of esophageal dysfunction and of gastroesophageal reflux.

There is an increased incidence of gastroesophageal reflux in children who have undergone repair of esophageal atresia.

OTHER CONGENITAL ESOPHAGEAL ABNORMALITIES

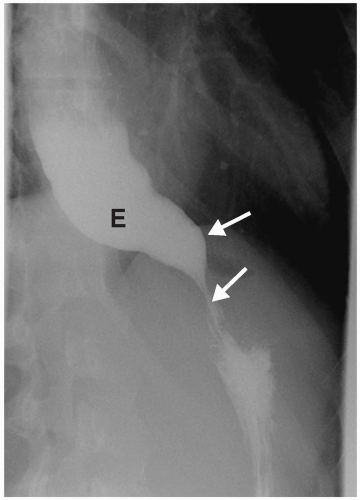

Other congenital causes of esophageal obstruction include achalasia and cartilaginous rings. Achalasia results from absence or degeneration of the myenteric plexus of the distal esophagus. Hence, the lower esophageal sphincter fails to relax, resulting in distal obstruction. Patients usually present in the second or third decade of life with dysphagia and weight loss. Radiographic findings include a dilated esophagus with air-fluid levels. Barium studies demonstrate esophageal dilatation, a tapered or beaklike appearance of the distal esophagus, and failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to open or relax (Fig. 7.5).

Radiographic findings of achalasia include a dilated esophagus with air-fluid levels.

In cartilaginous esophageal rings, tracheobronchial remnants, containing rests of respiratory tissue, are sequestered in the wall of the esophagus. Barium studies show a localized, funnel-shaped area of narrowing, nearly always in the distal one-third of the esophagus. Occasionally, small diverticula, representing tracheobronchial glands, extending perpendicularly from the esophagus can fill with barium.

STOMACH

Microgastria

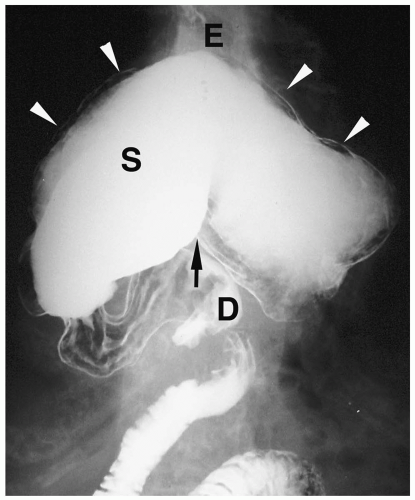

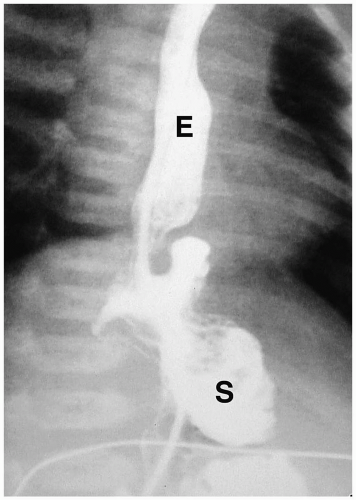

Microgastria is a rare anomaly characterized by a small, underdeveloped stomach (3). Associated malformations are common, including polysplenia and asplenia, colonic aganglionosis, midgut malrotation, and skeletal abnormalities. Imaging findings are a small, tubular, midline stomach and esophageal dilatation (Fig. 7.6).

Microgastria is a rare anomaly characterized by midline stomach and esophageal dilatation.

DUODENUM

Duodenal obstructions include duodenal atresia and stenosis, duodenal membrane, and annular pancreas (4,5).

Duodenal Atresia and Stenosis

Duodenal atresia is the most common cause of proximal bowel obstruction in the neonate and is believed to be the result of failure of recanalization of the duodenal lumen during fetal development. The atresia obstructs near the ampulla of Vater and leads to vomiting of bilious material within the first 24 hours of life. There is usually little or no upper abdominal distention because of the high anatomic level of the obstruction and the vomiting. Other anomalies are present in about one half of patients, including Down syndrome (found in approximately 30%), malrotation, congenital heart disease, esophageal atresia, renal anomalies, and imperforate anus.

Duodenal atresia is the most common proximal bowel obstruction in the neonate.

Other anomalies are present in about 50% patients.

Figure 7.6 Microgastria. UGI demonstrates a small midline stomach (S) and a dilated distal esophagus (E). (Image courtesy of D. Gregory Bates, M.D., Columbus, Ohio.) |

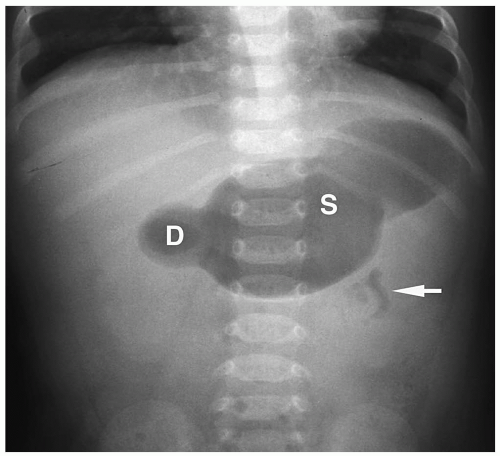

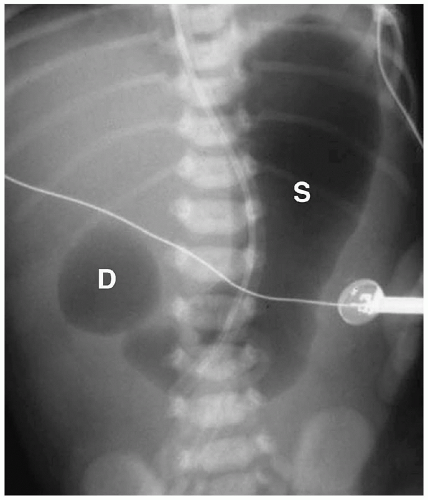

Figure 7.7 Duodenal atresia. Supine radiograph demonstrates gas in the stomach (S) and markedly dilated duodenal bulb (D), producing the double bubble sign. The remainder of the abdomen is gasless. |

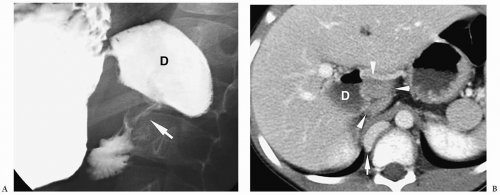

Figure 7.8 Duodenal atresia. Right lateral oblique image from an upper GI series shows dilatation of the duodenal bulb (D) and failure of barium to pass beyond. |

Abdominal radiography usually shows gas in a dilated stomach and duodenal bulb, producing a classic double bubble sign (Fig. 7.7). With this appearance, further imaging studies are unnecessary. However, if the patient has vomited or a nasogastric tube has been placed, the stomach and the duodenum may be collapsed. In these cases, a barium upper GI series may be needed for diagnosis (Fig. 7.8). Air may be seen in the distal small bowel in some patients with duodenal atresia if they also have a bifurcated common bile duct with one branch inserting above the site of atresia and one branch below beside the site of atresia. Patients with this form of the anomaly also may need an upper GI series for diagnosis.

Double bubble sign is classic for the diagnosis of duodenal atresia or stenosis.

Duodenal Membrane

Duodenal membrane or web is an intraluminal diaphragm that arises near the ampulla of Vater and may be complete or partial, depending on the presence or absence of an aperture. If the diaphragm is complete, the patient presents with bilious vomiting and a doublebubble pattern on plain radiographs, indistinguishable from that seen in duodenal atresia. If the web is incomplete, patients can present after the neonatal period with vomiting or abdominal pain. In these patients, a thin, convex curvilinear structure may be seen extending across the lumen of the second portion of the duodenum on the UGI study, producing a “windsock” deformity (Fig. 7.9).

Duodenal membranes arise near the ampulla of Vater.

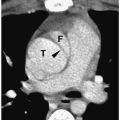

Annular Pancreas

Annular pancreas is an anomaly in which normal pancreatic tissue encircles the second portion of the duodenum. It is nearly always associated with duodenal atresia or stenosis, which is probably the cause of obstruction. If the obstruction is severe, patients present shortly after birth with bilious vomiting, mimicking duodenal atresia. With lesser degrees of obstruction, patients may be asymptomatic or present later in childhood with symptoms of obstruction. In these patients, barium examination shows duodenal narrowing. CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can confirm the diagnosis by showing the anomalous pancreatic tissue encasing the duodenum (Fig. 7.10). Treatment involves surgically bypassing the obstruction with a side-to-side anastomosis.

Annular pancreas is associated with duodenal atresia or stenosis.

JEJUNUM

Jejunal Atresia and Stenosis

Jejunal atresia and stenosis are also causes of proximal neonatal intestinal obstruction. Atresia is more common than stenosis. Both anomalies are more common in the proximal jejunum and distal ileum than in other areas of the small bowel. Both are thought to result from an in utero ischemic injury. Affected neonates usually present in the first 24 hours of life with bilious vomiting, abdominal distension, and failure to pass meconium. Abdominal distension is more severe than with duodenal obstruction.

Jejunal Atresia is more common than stenosis.

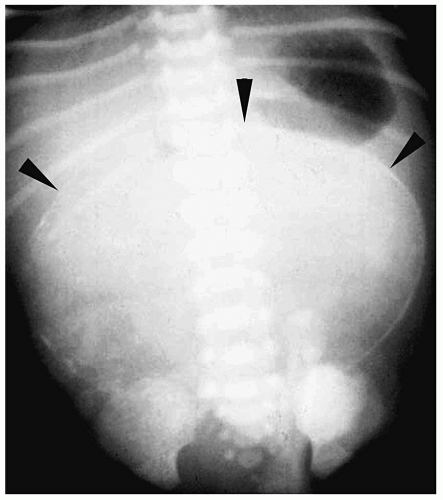

Plain radiographs show dilated loops of proximal small bowel. The remainder of the abdomen is gasless (Fig. 7.11). Air-fluid levels, peritoneal calcification due to in utero perforation, and intraluminal calcifications may also be noted. An upper GI series is not

needed for diagnosis, but some surgeons may request a contrast enema examination to exclude other sites of atresia in the distal small bowel. With an isolated jejunal atresia, the colon is of normal or near normal caliber, as adequate amounts of succus entericus reach it. If there are also sites of distal atresia, the colon will be small. Treatment is resection of the atretic sites and primary anastomosis.

needed for diagnosis, but some surgeons may request a contrast enema examination to exclude other sites of atresia in the distal small bowel. With an isolated jejunal atresia, the colon is of normal or near normal caliber, as adequate amounts of succus entericus reach it. If there are also sites of distal atresia, the colon will be small. Treatment is resection of the atretic sites and primary anastomosis.

In jejunal atresia, plain radiographs show dilated loops of proximal small bowel.

ILEUM

Ileal atresia and meconium ileus are causes of distal bowel obstruction. Water soluble contrast enema examination is the study of choice to evaluate a suspected distal small bowel obstruction. The most important differential diagnostic finding on the contrast examination is the presence or absence of a microcolon. A microcolon is an unused colon. It has an extremely small caliber, usually <1 cm in diameter. The presence of a microcolon indicates a distal small bowel obstruction, usually meconium ileus or ileal atresia. Less often microcolon is due to total colonic Hirschsprung disease (see section on Colon).

Ileal Atresia

Meconium Ileus

Meconium ileus is a congenital bowel obstruction that results from inspissation of abnormally sticky meconium in the distal small bowel. It is almost always a manifestation of cystic fibrosis, and approximately 10% to 20% of patients with cystic fibrosis present in the neonatal period with meconium ileus.

Meconium ileus is a manifestation of cystic fibrosis.

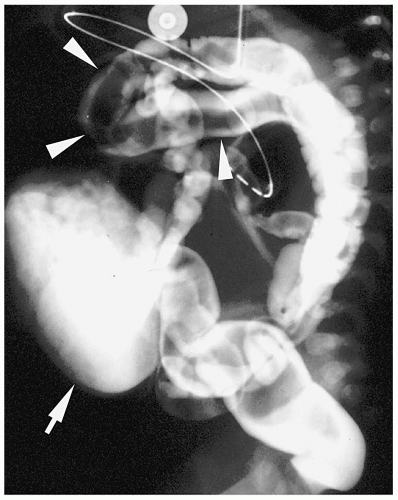

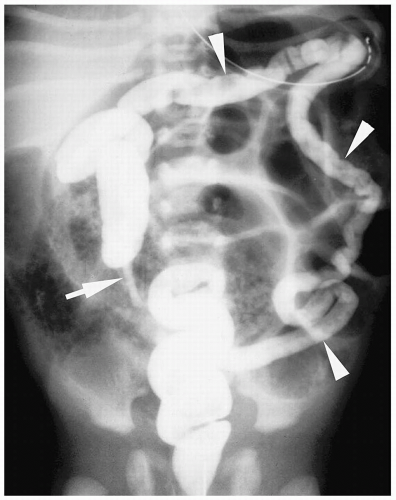

Figure 7.13 Ileal atresia. Same patient as in Figure 7.12. Contrast fills the unused microcolon (arrowheads) and appendix (arrow). There is no reflux of contrast into the terminal ileum. |

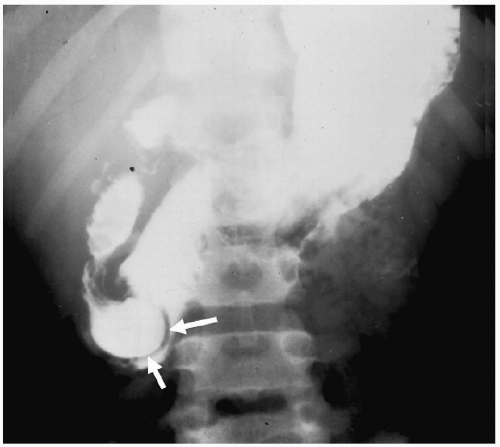

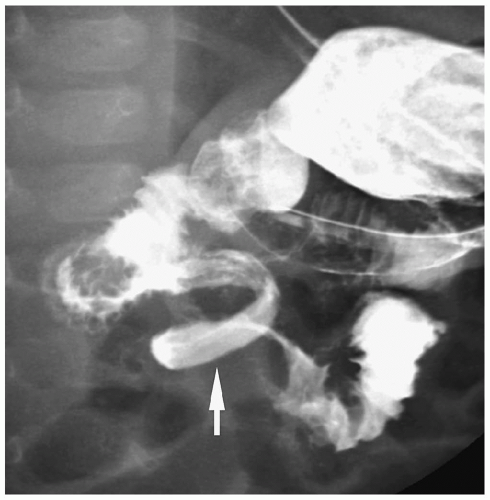

Figure 7.14 Meconium ileus. A contrast enema demonstrates a microcolon (arrows) from disuse. The distal ileum is dilated and contains multiple pellets of meconium (arrowheads). |

Plain radiographs show distal bowel obstruction indistinguishable from that seen in other distal small or large bowel obstruction. Water-soluble enema findings include a microcolon and impacted meconium, which appears as multiple ovoid or round filling defects in the terminal ileum (Fig. 7.14). Contrast usually can be refluxed into proximal distended loops of ileum. Therapeutic enemas are less likely to be successful in infants with meconium ileus complicated by other pathology (i.e., volvulus, perforation, atresia).

Enema findings in meconium ileus include a microcolon and impacted meconium.

Meconium Peritonitis and Pseudocyst

Meconium peritonitis is an aseptic peritonitis caused by antenatal perforation of bowel and intraperitoneal spill of meconium. It is usually associated with bowel atresias and meconium ileus. Calcifications can develop as early as 12 hours after in utero perforation (Fig. 7.15). Although peritoneal calcification is most common, calcifications also can be seen in the scrotum and bowel wall.

Meconium peritonitis is usually associated with bowel atresias and meconium ileus.

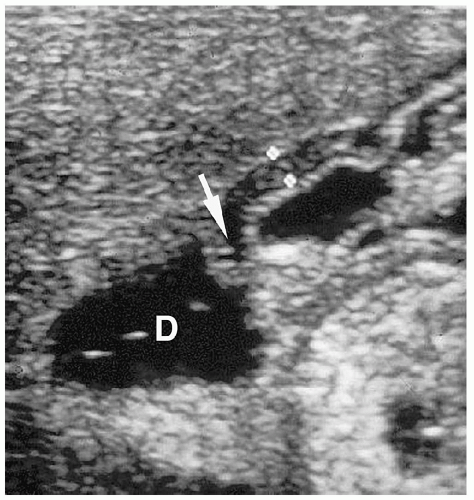

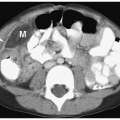

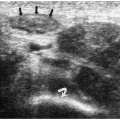

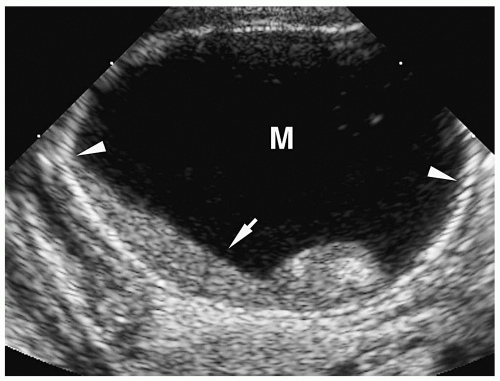

Meconium pseudocyst is a cyst-like mass that results when the extruded meconium becomes walled off by fibrous adhesions. The cysts can contain only meconium or a combination of meconium and trapped bowel loops. Plain radiography shows a soft-tissue mass, which may have an air-fluid level and a calcified wall (Fig. 7.16). Contrast enema can demonstrate communication with the bowel (Fig. 7.17). Sonographic findings include a fluid-filled mass, echogenic walls due to calcifications, and internal echoes due to the presence of air or debris (Fig. 7.18).

Meconium pseudocyst results when extruded meconium becomes walled off.

COLON

Functional immaturity of the colon and Hirschsprung disease are also common causes of distal bowel obstruction. Less frequent causes of neonatal distal bowel obstruction include anorectal malformations, colonic atresia, and megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (6,7).

Hirschsprung Disease

Hirschsprung disease is a functional colonic obstruction, which is characterized by the absence of ganglion cells in the distal colon. The aganglionic segment most often involves only the rectum and a part of the sigmoid colon (termed short segment disease). It also may extend into the descending colon (long segment disease) or it may involve the entire colon and distal small bowel (total colonic disease). Hirschsprung disease affects males more than females and is a disease of term infants. Patients present in the neonatal period or in childhood with constipation and abdominal distension. Enterocolitis is a complication of severe disease.

Hirschsprung disease is a functional colonic obstruction, characterized by the absence of ganglion cells in the distal colon.

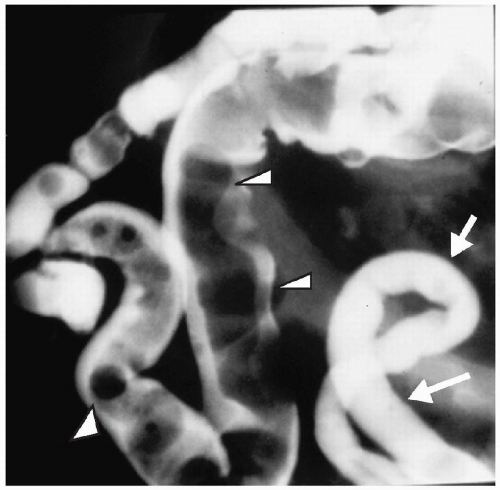

Plain radiographs demonstrate small bowel obstruction. A barium contrast enema provides a definite diagnosis. Barium is preferred over the water soluble contrast agents because it is better for demonstrating the poor colonic evacuation associated with Hirschsprung

disease. No bowel preparation should be given, and a catheter without a balloon should be placed low in the rectum to avoid obscuring the transition zone between the aganglionic and normal colon. The classic finding of Hirschsprung disease is a transition zone from small aganglionic bowel to more dilated normally innervated proximal bowel (Fig. 7.19). The transition zone may be difficult to detect in the newborns. In these patients, measurement of the rectosigmoid (R/S) index can help in the diagnosis. In neonates with Hirschsprung disease, the maximal diameter of the rectum is smaller than that of the maximal diameter of the sigmoid colon (R/S index <1) (Fig. 7.20). In normal newborns, the rectal diameter is larger than that of the sigmoid colon (R/S ratio >1). Other findings are irregular, sawtooth contractions of the aganglionic segment and delayed evacuation of barium on radiographs obtained 24 hours after the examination. In the presence of colitis, the enema may show mucosal thickening, due to edema and ulceration.

disease. No bowel preparation should be given, and a catheter without a balloon should be placed low in the rectum to avoid obscuring the transition zone between the aganglionic and normal colon. The classic finding of Hirschsprung disease is a transition zone from small aganglionic bowel to more dilated normally innervated proximal bowel (Fig. 7.19). The transition zone may be difficult to detect in the newborns. In these patients, measurement of the rectosigmoid (R/S) index can help in the diagnosis. In neonates with Hirschsprung disease, the maximal diameter of the rectum is smaller than that of the maximal diameter of the sigmoid colon (R/S index <1) (Fig. 7.20). In normal newborns, the rectal diameter is larger than that of the sigmoid colon (R/S ratio >1). Other findings are irregular, sawtooth contractions of the aganglionic segment and delayed evacuation of barium on radiographs obtained 24 hours after the examination. In the presence of colitis, the enema may show mucosal thickening, due to edema and ulceration.

Figure 7.18 Meconium pseudocyst. Transverse sonogram of the right upper quadrant shows a cystic mass (M) with a calcified rim (arrowheads) containing layering internal debris (arrow). |

Figure 7.19 Hirschsprung disease. Enema of a 1-month-old girl with Down syndrome and constipation since birth. There is a transition zone (arrow) in the sigmoid colon with proximal dilatation. |

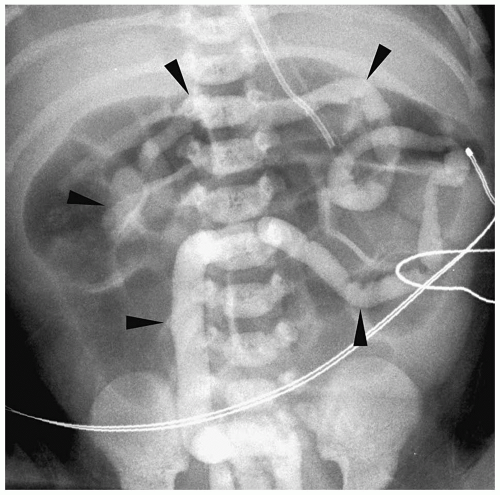

Figure 7.21 Total colonic hirschsprung disease. The entire colon is small in caliber (arrowheads). The histologic transition zone was in the distal ileum. |

Findings of total colonic Hirschsprung disease include a normal caliber colon, a short foreshortened colon with absent flexures, and a microcolon (Fig. 7.21). Additional findings include dilated small bowel and intraluminal small bowel calcifications. Total colonic aganglionosis has an equal incidence in males and females and may be familial.

Findings of total colonic Hirschsprung disease include normal caliber colon, shortened colon, and microcolon.

Functional Immaturity of the Large Bowel

Functional immaturity of the neonatal colon, previously known as the small left colon or meconium plug syndrome, is a transient abnormality of intestinal motility presenting at

birth. The affected newborn fails to pass meconium and develops abdominal distention. This condition is found in premature infants, small-for-dates infants, and infants of diabetic mothers. It is usually self-limited, although cecal perforation has been described.

birth. The affected newborn fails to pass meconium and develops abdominal distention. This condition is found in premature infants, small-for-dates infants, and infants of diabetic mothers. It is usually self-limited, although cecal perforation has been described.

Functional immaturity of the neonatal colon is a transient abnormality of intestinal motility.

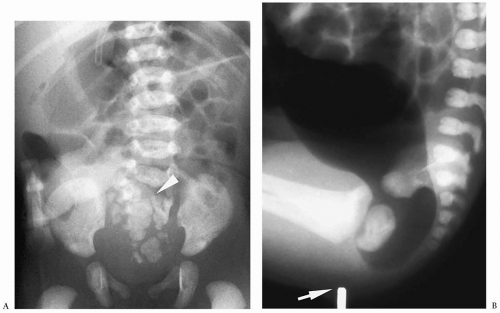

Plain radiographs show a distal bowel obstruction. Contrast enema reveals a narrow descending and rectosigmoid colon with a transition point to a normal caliber colon near the splenic flexure (Fig. 7.22). The rectum, transverse, and right colon are normally distensible. A variable amount of meconium is noted in the narrowed segment of colon. Water-soluble enemas are useful for diagnosis and also treatment, because they facilitate passage of meconium. Passage of normal stools is noted within several days. The normal size of the rectum, premature age of the infants, and quick improvement in symptoms helps differentiate functional colonic immaturity from Hirschsprung disease.

In functional colonic immaturity, contrast enema reveals a narrowed descending and rectosigmoid colon.

Anorectal Malformations

Anorectal malformation, also referred to as imperforate anus, is the result of abnormal separation of the hindgut from the genitourinary system. The absence of a normal anus is diagnostic on physical examination. Anorectal malformations are classified as high or low, depending on whether the rectum terminates above or below the levator ani. In boys with high lesions, the rectum usually ends with a fistula to the posterior urethra or rarely to the bladder. In girls with high lesions, the fistula is to the vagina or vestibule. In low lesions, the rectum has no communication with the genitourinary tract. Patients with low lesions may have a tiny perineal orifice that is anteriorly positioned relative to the expected normal position or the rectum may be completely covered. The differentiation between high and

low lesions can usually be made clinically, based on visualization of a perineal orifice or the passage of meconium through the urethra or vagina.

low lesions can usually be made clinically, based on visualization of a perineal orifice or the passage of meconium through the urethra or vagina.

Anorectal malformations are classified as high or low lesions.

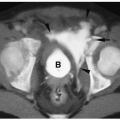

Plain radiographs reveal a distal bowel obstruction. Air may be noted in the bladder in boys with high lesions. Calcified meconium also may be noted in the bowel. Anorectal malformations are part of the VACTERL association (see prior discussion) (Fig. 7.23). Renal abnormalities include hydronephrosis, horseshoe kidney, renal agenesis and hypoplasia, and vesicoureteral reflux. Associated anomalies are more common in neonates with high lesions.

Anorectal malformations are part of the VACTERL association.

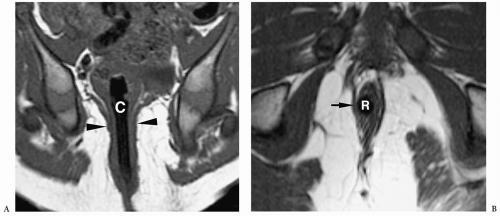

Surgery for the low-type imperforate anus is usually done soon after birth and involves closure of the fistula, creation of an anal opening, and repositioning the rectal pouch into the anal opening. Surgery for a high-type imperforate anus defect initially involves creation of a colostomy. The infant is allowed to grow for several months and then a complete repair is done. In this repair, the rectal pouch is pulled down, an anal opening is created, and the colostomy is closed. Incontinence or constipation are complications after repair. In these instances, MRI can be helpful in showing the position of the neorectum and whether it is adequately positioned within the levator sling (Fig. 7.24).

Colonic Atresia

Colonic atresia is a relatively uncommon cause of neonatal bowel obstruction. The atresia occurs proximal to the rectum, usually in the descending or transverse colon. The two parts of the colon may be separated by a fibrous cord, complete gap, or membrane (web). Infants present immediately after birth with abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, and failure to pass meconium. Plain radiographs demonstrate a distal bowel obstruction and commonly disproportionately dilated bowel loops on the right side of the abdomen, representing dilated proximal colon (Fig. 7.25). Contrast enema shows a microcolon distal to the site of atresia and no flow proximally. In the membranous type of colonic atresia, the membrane prolapses in a retrograde fashion into the more proximal colon, creating a “windsock” deformity.

Colonic atresia occurs usually in the descending or transverse colon.

Megacystis-Microcolon-Intestinal Hypoperistalsis Syndrome

Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome is a rare cause of distal bowel obstruction. Contrast enema shows a microcolon, which is likely due to decreased small bowel motility. The small bowel also may be short and malrotated. Sonography reveals a large bladder, hydronephrosis, and ureteral dilatation. Long-term prognosis is poor.

ACQUIRED BOWEL OBSTRUCTIONS

STOMACH

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is a disorder characterized by hypertrophy of the circular muscle of the pylorus, which results in gastric outlet obstruction (8). Boys are affected 4 to 5 times more than girls, and there is a familial predisposition. HSP develops in approximately 20% of sons and 7% of daughters of female index cases and 5% of sons and 2% of daughters of male index cases. Typically, patients present between 2 and 6 weeks of age with nonbilious vomiting, which often becomes projectile. The clinical diagnosis of HPS can be made when an olive-shaped mass is palpated in the epigastrium. The treatment for HPS is a Ramstedt pyloromyotomy, in which the hypertrophic muscle is split longitudinally without violating the mucosa.

Pyloric stenosis presents between 2 and 6 weeks of age with nonbilious vomiting.

Ultrasonography.

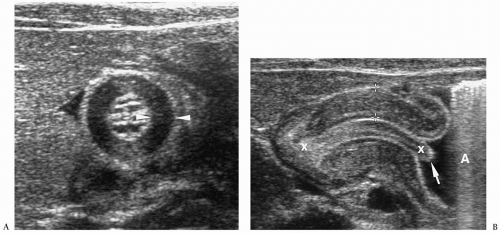

Sonography is the diagnostic modality of choice to confirm the diagnosis of HPS (8,9,10). The sonographic examination is performed with a high-frequency lineararray transducer. The pylorus is viewed in the longitudinal and transverse planes, with the infant in the right posterior oblique position. The stomach should not be emptied prior to the examination, because this makes identification of the antropyloric area difficult. If the stomach does not contain adequate fluid, a glucose solution or water should be given orally or via a nasogastric tube to distend the antrum.

Sonography is the diagnostic modality of choice to confirm the diagnosis of HPS.

On short-axis views, the thickened muscle has a bull’s-eye appearance with thickened hypoechoic muscle surrounding echogenic mucosa. Long-axis views of the pylorus show

the thickened muscle and elongated pyloric channel (Fig. 7.26). Other findings include gastric hyperperistalsis, reflux, and absent or minimal gastric emptying.

the thickened muscle and elongated pyloric channel (Fig. 7.26). Other findings include gastric hyperperistalsis, reflux, and absent or minimal gastric emptying.

The normal pyloric muscle is 2 mm or less in thickness. A muscle thickness equal to or greater than 3 mm and a pyloric channel length greater than 17 mm are considered diagnostic of HPS. Measurements between 2.0 and 2.9 mm are abnormal but nonspecific and can be seen with gastritis or pylorospasm as well as with HPS. Premature infants are particularly likely to have borderline muscle thickness. However, they have other sonographic findings of HPS, such as elongation of the pyloric canal, poor emptying, and hyperperistalsis.

A muscle thickness ≥3 mm and a pyloric channel length > 17 mm are considered diagnostic of HPS.

Upper GI Series.

A barium upper GI series is reserved for infants who have an equivocal or negative sonogram and a persistent clinical suspicion of pyloric stenosis. The classic findings on contrast examination are an elongated and narrowed pyloric channel (string sign), mass effect of the hypertrophied muscle on the gastric antrum (shoulder sign), barium in the proximal pyloric channel (beak sign), and a collection of barium along the lesser curvature as a result of a peristaltic wave along the lesser curvature (teat sign) (Fig. 7.27). Occasionally, barium may be noted on either side of the elongated pyloric channel (double-track sign). Gastric emptying is virtually always delayed.

Pylorospasm

Pylorospasm is a disorder characterized by transient spasm of the pylorus. Patients present with vomiting. Barium and sonographic findings include antral narrowing and delayed, but intermittent, gastric emptying. At sonography, pyloric muscle thickness and channel length are normal. The intermittent flow of gastric contents into the duodenum helps to differentiate pylorospasm from pyloric stenosis (Fig. 7.28).

In pylorospasm, pyloric muscle thickness and channel length are normal.

Prostaglandin E

Prostaglandin E is given to maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus in newborns with cyanotic heart disease and results in hyperplasia of the gastric mucosa, which may produce gastric outlet obstruction. The upper GI series shows an elongated pyloric channel. Sonography shows that the narrowing is secondary to mucosal hyperplasia and not to muscle hypertrophy. The hyperplasia disappears when therapy is discontinued.

Prostaglandin E may produce gastric outlet obstruction.

Gastric Volvulus

Gastric volvulus is classified as organoaxial or mesenteroaxial. Patients present with vomiting. Organoaxial volvulus is rotation of the stomach around its long axis, which results in the greater curvature positioned superiorly and the inferior curvature positioned inferiorly (Fig. 7.29). It often is associated with diaphragmatic hernia or eventration. Mesenteroaxial volvulus is rotation of the stomach around an axis perpendicular to the stomach, which results in the gastric antrum lying superiorly and anteriorly and to the left of midline and near the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 7.30). The obstruction may occur at the gastroesophageal junction or at the pylorus. In both types of volvulus, abdominal radiographs show gastric dilatation. Contrast studies reveal the abnormal rotation.

Gastric volvulus is classified as organoaxial or mesenteroaxial.

SMALL BOWEL

Midgut Malrotation

Malrotation refers to a spectrum of rotational abnormalities including failure of rotation (colon to the left, small bowel to the right), reverse nonrotation (small bowel to the left, colon to the right), reverse rotation (duodenum anterior and colon posterior to the superior mesenteric artery, small bowel to the right, cecum malpositioned), and incomplete rotation (a range of abnormalities between nonrotation and normal rotation). In malrotation, the

attachment of the bowel is abnormally short, resulting in a narrowed mesenteric pedicle and an abnormally positioned ligament of Treitz.

attachment of the bowel is abnormally short, resulting in a narrowed mesenteric pedicle and an abnormally positioned ligament of Treitz.

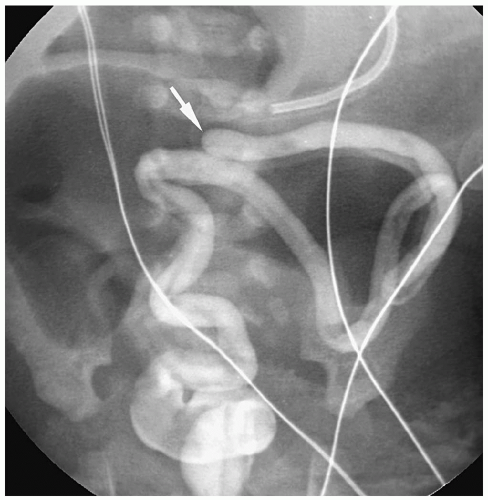

Figure 7.33 Malrotation with midgut volvulus. Image from an UGI in a newborn with bilious vomiting shows the classic spiral or corkscrew appearance of the duodenum (arrow). |

Symptoms in patients with malrotation are a result of a proximal bowel obstruction from extrinsic peritoneal bands (Ladd bands) crossing the third portion of the duodenum, midgut volvulus, or a combination of the abnormalities (11). Patients with malrotation usually present in the first month of life with vomiting, which is nearly always bilious. Older children can present with diarrhea and malabsorption caused by mesenteric lymph stasis or with intermittent abdominal pain and vomiting from episodic volvulus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree