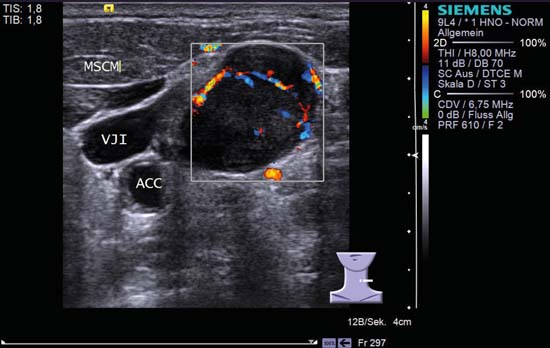

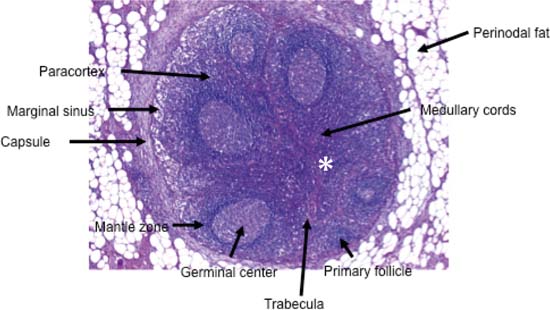

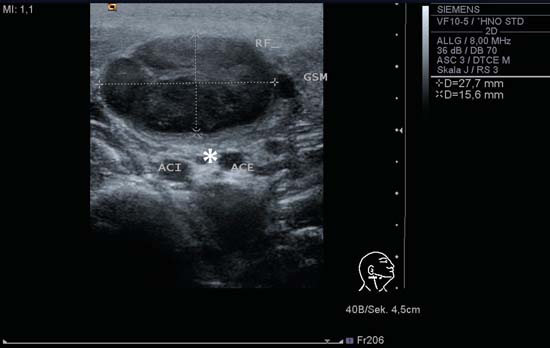

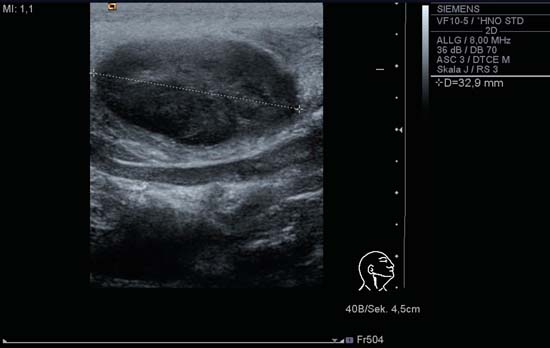

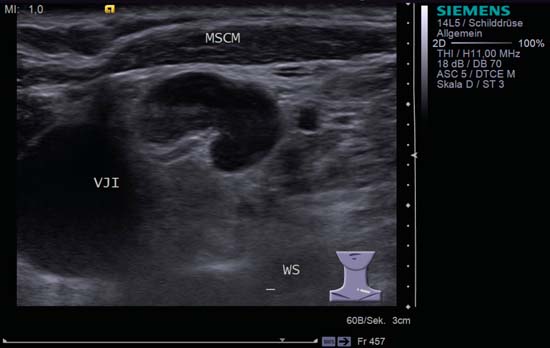

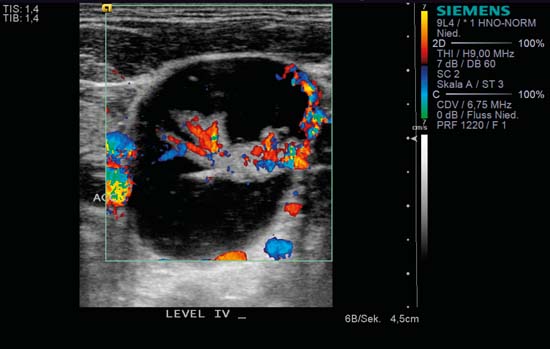

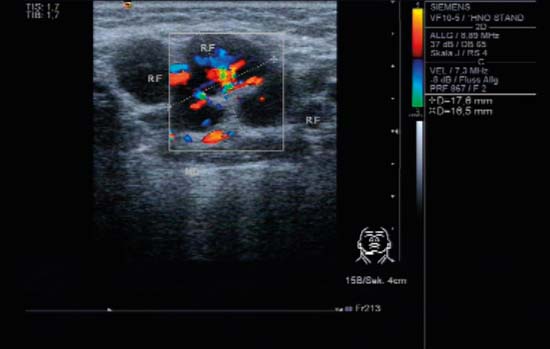

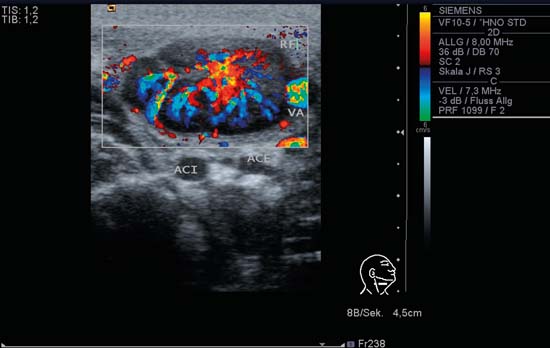

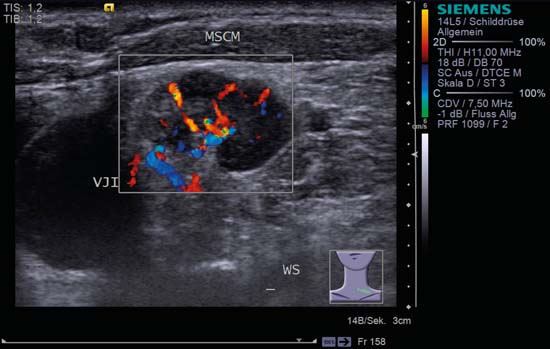

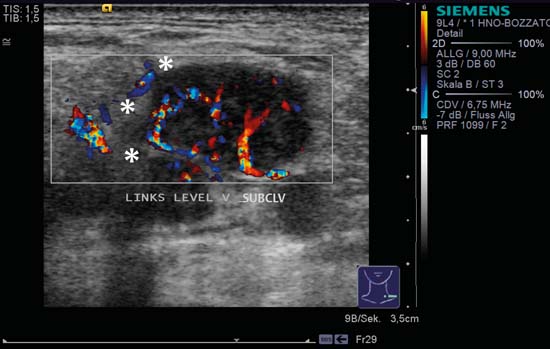

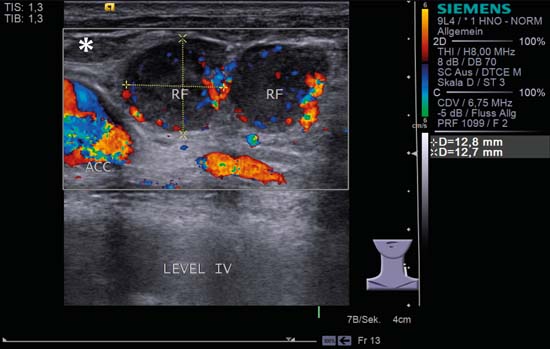

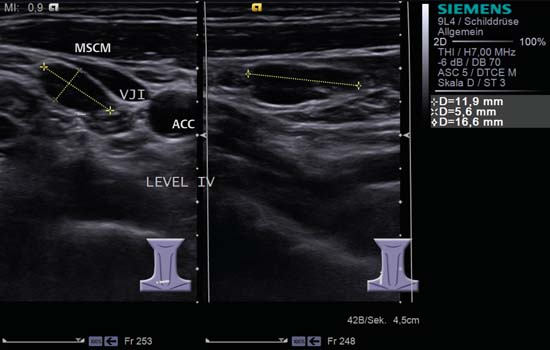

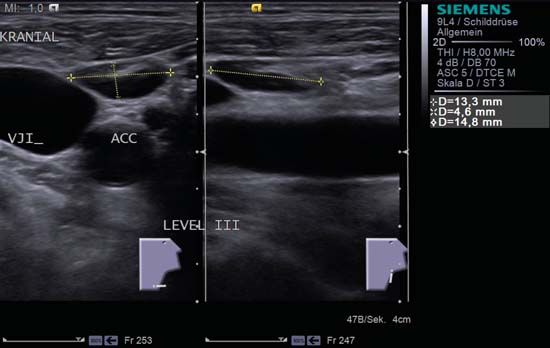

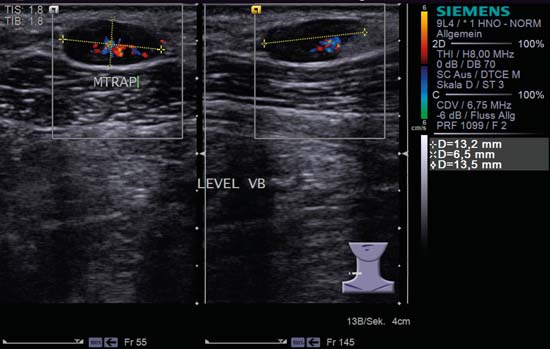

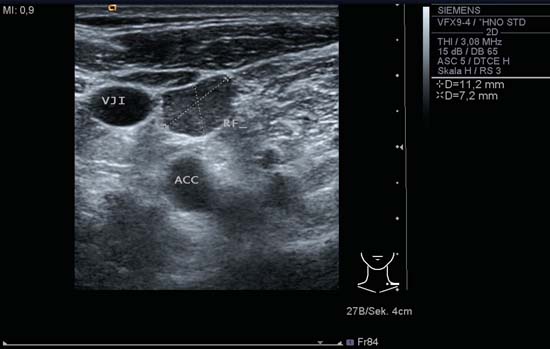

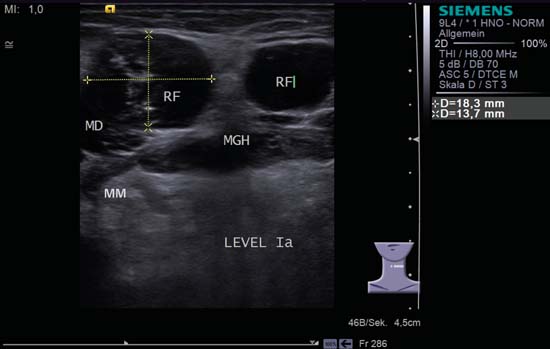

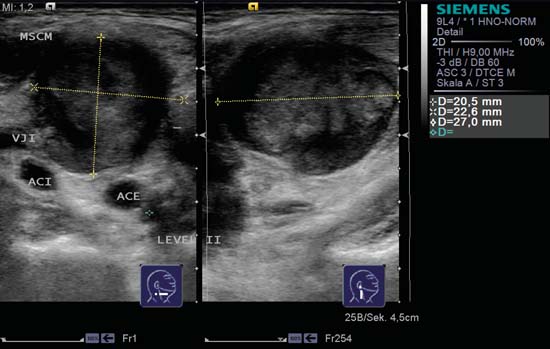

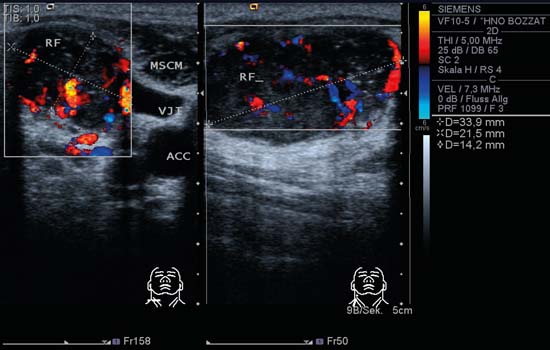

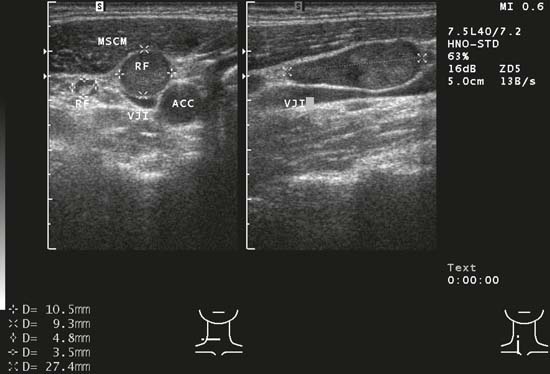

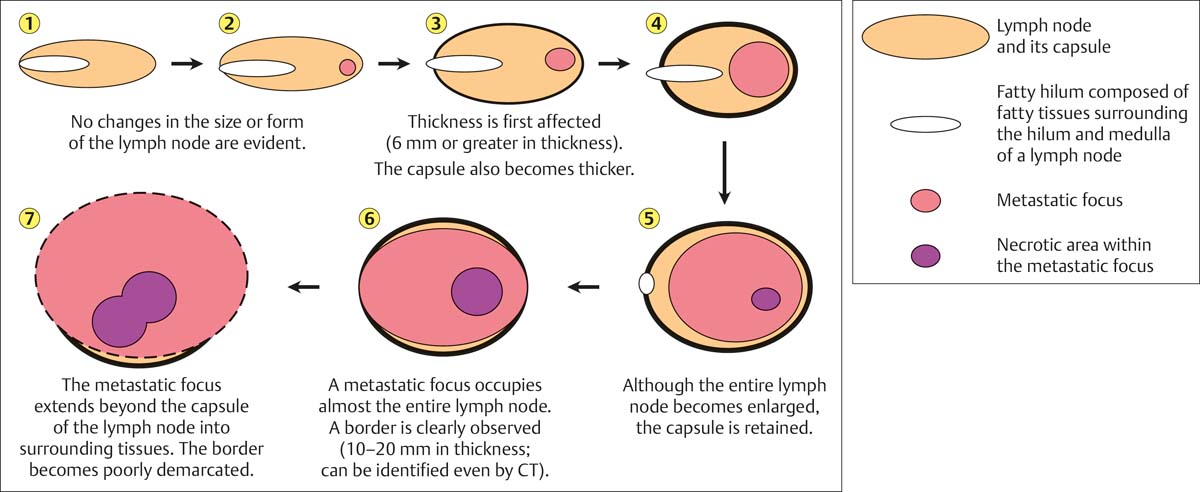

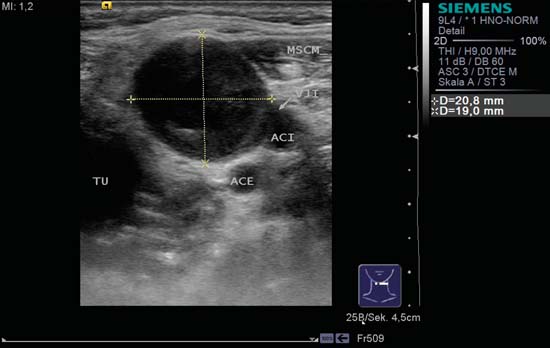

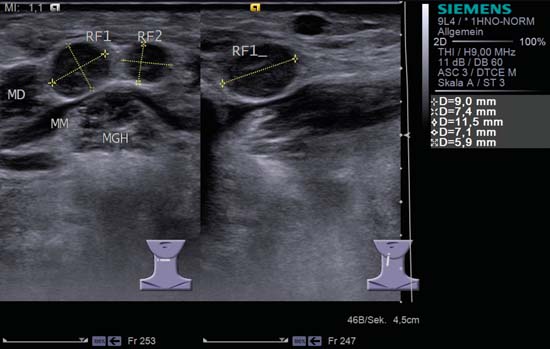

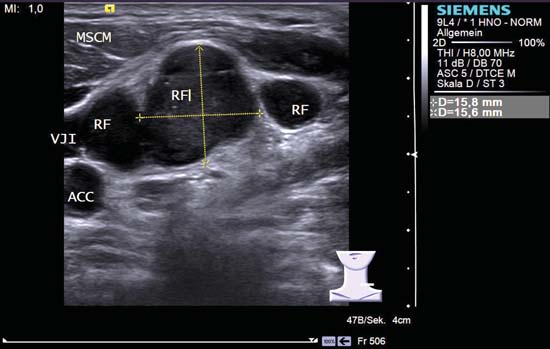

6 Neck Lymph Nodes The use of ultrasound has been validated in examination of the superficial structures of the head and neck as considerably more sensitive than clinical assessment through palpation in the identification and interpretation of the 200–300 lymph nodes of the neck and soft tissues changes in this region. Given the optimal exposure of the cervical soft tissues and the high spatial resolution, diagnostic ultrasonography is the first choice of method, as lymph nodes exceeding 3 mm are easy to identify. The patient is usually examined with the neck hyperextended (see Chapters 3 and 4). Figure 6.1 shows the histological appearance of a typical cervical lymph node. The sonographic appearance of cervical lymph nodes on high-resolution ultrasound reflects their structure and has some distinctive characteristics. Lymph nodes in the neck are oval or ellipsoid in shape. Within the node, there is generally a hypoechoic marginal zone, which can be distinguished from the central hyperechoic hilar region (the medullary sinuses with blood vessels and efferent lymph vessels). Although the size of a lymph node in the neck may be used as a classification criterion, this is not without problems. Owing to the typical physiological configuration of cervical lymph nodes (oval/ellipsoid), the node should always be measured in all three orthogonal planes: the diameter is measured in one long axis and two short axes (Figs. 6.2a, b). Pearls and Pitfalls There is a danger of confusing lymph nodes in level II, which are commonly found at the posterior border of the submandibular gland, with the posterior belly of the digastric muscle sliced obliquely or in cross-section. The pinnate structure of the muscle can mimic a lymph node hilus. Rotating the probe by 90° “over the finding” allows an identification to be quickly made. Most work assessing lymph nodes on the basis of their size refers to the short-axis diameter. The existing limits of short-axis size, above which a lymph node is suspected of being malignant, vary with the level of the node (levels IB and II: ~8 mm; levels IA, III, IV, V: ~5 mm). As routine practice shows, these limits cannot be used unreservedly. Small nodes with malignant changes often have measurements below the cut-off value and, conversely, enlarged reactive lymph nodes (e.g., in infectious mononucleosis) can be considerably larger. The overall clinical constellation is decisive for the assessment. There is currently no imaging technique that allows the certain classification of micrometastases or small metastases with a maximum diameter of less than 3 mm. A pinecone-shaped echogenic structure protruding from the center of the node can be seen in grayscale images (Figs. 6.3, 6.4, 6.5). It is sometimes referred to as the “hilar sign” or “hilus sign” and is a normal part of the lymph node morphology. Absence of this hyperechoic central structure in the hilar region may be considered a criterion for malignancy. Malignant transformation causes changes in or loss of the lymph node structure, with reduction or erosion of the central hilar complex. The “hilar sign” is confirmed by the use of color-coded duplex sonography (CCDS), which shows color-coded hilar perfusion in the echogenic central area. Blood vessels leading to and from the node can be seen in the hilum, corresponding to the histological structure (Fig. 6.6; The perfusion pattern can be used to determine the angioarchitecture of the node, so that any pathological changes can be identified. Tschammler and co-workers described distinct patterns for enlarged lymph nodes in CCDS, indicating malignant or nonmalignant origin. Enlarged reactive lymph nodes show a vascular pattern originating in the hilum and branching radially or like the spokes of a wheel (Figs. 6.5, 6.7, 6.8; Changes from the normal structure that may be considered suspicious of malignancy include decentralized vascularity, peripheral perfusion or an avascular focus (Fig. 6.9). In the characteristic appearance of a metastasis, the vessels are distributed peripherally around the capsule of the node (subcapsular; Fig. 6.10; The rationale for including lymph node shape as a criterion of malignancy is that an oval/kidney-shaped lymph node increases in volume during an inflammatory process. The oval or spindle shape is maintained when changes are reactive (Figs. 6.3, 6.11, 6.12, 6.13), but malignant transformation causes the node to become more rounded. The Solbiati Index (cutoffvalue 1.5 or 2.0), which represents the lymph node morphology in terms of the ratio of the long- to short-axis ratio (L/S ratio), is frequently used. A node with an index <2.0 is suspected of being malignant. Pearls and Pitfalls Lymph nodes in levels IA and IB, the nuchal and the parotid regions, normally have a rounded shape. Beware of suspecting malignancy too quickly when assessing nodes in these areas. Cervical lymph nodes are usually well demarcated from surrounding tissues and freely mobile on sonographic palpation. In addition to demonstrating the layers of impedance, the zoom function of the ultrasound system allows a precise determination of the node’s movement during arterial pulsation from the surroundings (Figs. 6.14, 6.15; If there are signs of extensive infiltration, the differentiation between strong inflammatory changes and neoplastic enlargement can usually be made on the basis of the clinical situation. During inflammatory processes, poor demarcation of the lymph node on ultrasound indicates a process extending beyond the capsule, such as an abscess or a phlegmon. With malignant transformation (metastasis, lymphoma), ill-defined margins or club-shaped thickenings are considered indicative of neoplastic enlargement/infiltration of the lymph node capsule and therefore, with high sensitivity and specificity, as clear criteria of malignancy (Figs. 6.16, 6.17). Mobility of the nodes within their sheaths is reduced or absent. Fig. 6.1 Histology of a typical cervical lymph node. The trabeculae extending centrally from the periphery represent the lymph node hilum and contain, among other things, the blood vessels (asterisk). (Reproduced with kind permission of A. Agaimy MD, Institute of Pathology, Erlangen University Hospital, Germany.) Fig. 6.2a Right side of the neck, transverse, level II. An oval lymph node in acute lymphadenitis colli (RF); the node has a delicate internal echo pattern with well-defined margins and measures 30 mm × 15 mm in both short-axis diameters. A clearly visible incidental finding is the nerve bundle of the vagus nerve seen in cross-section between the internal (ACI) and external (ACE) carotid arteries (asterisk). GSM, submandibular gland. According to classical teaching, the lymph node cortex (hypoechoic) and hilum (echogenic) show a homogeneous structure on ultrasound (Fig. 6.18). The presence of a markedly inhomogeneous echotexture is a relevant criterion of malignancy (Figs. 6.19, 6.20, 6.21). Pearls and Pitfalls It is becoming problematic that the latest ultrasound scanners with higher resolution and improved displays hardly ever show completely homogeneous lymph nodes; rather they nearly always demonstrate some inhomogeneous—but not actually malignant— textural elements. If the lymph node structure is altered as the result of a malignant transformation, the distinction between cortex and hilum is lost (Fig. 6.22). The echotexture is inhomogeneous with anechoic areas indicating necrosis and reduced perfusion of the center of the tumor (Figs. 6.23, 6.24). On the other hand, a central anechoic area in a reactive cervical lymph node is typical of abscess formation. Liquefaction with a central anechoic area is seen particularly in mycobacteria infections and actinomycosis (see below). In contrast, echogenic reflections or calcification are characteristically seen in tuberculosis and in the case of metastases of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. If there is an inflammatory process, the lymph nodes in the drainage channels of the affected organs show reactive changes. Hugely enlarged cervical lymph nodes in the lower neck are relatively less often affected by inflammation and are therefore detectable more often in the presence of malignancy. The overall clinical situation must also be taken into account to be able to make an appropriate assessment (Fig. 6.25). Noting the distribution of lymphadenopathy helps in narrowing down the differential diagnosis (Figs. 6.26, 6.27). Lymph node metastases from solid tumors are usually found initially in groups sited in the relevant lymphatic drainage channels. Particularly in cervical cases, the manifestation of many types of malignant lymphoma tends to appear in a conglomerate pattern. Pearls and Pitfalls The ultrasound criteria for assessing whether or not a cervical lymph node is malignant are: 1. Size and three-dimensional proportions 2. Detectability of a lymph node hilus, perfusion pattern 3. Lymph node shape 4. Border of the lymph node 5. Homogeneity of the intranodal structure 6. Distribution of the lymph nodes Fig. 6.2b Right side of the neck, longitudinal, level II. The oval lymph node seen in acute lymphadenitis colli measures 32 mm on its long axis. Fig. 6.3 Left side of the neck, transverse, level V. This lymph node shows a characteristic pattern of inflammation (kidney shape, hilar sign, homogeneous texture). MSCM, stemocleidomastoid muscle, VJI, internal jugular vein, WS, vertebral spine. Fig. 6.4 Left side of the neck, transverse, CCDS. A round, clearly defined lymph node lateral to the common carotid artery (ACC), with a classical “hilar sign” and hilar perfusion seen on CCDS. The afferent and efferent hilar vessels can also be identified at the right border of the node. In this case, the massive enlargement of the node with maintenance of the normal vascular and hilar structures was due to non-Hodgkin lymphoma. A cystic mass in the lower neck area may also be found with metastases of papillary thyroid carcinomas. Fig. 6.5 Submandibular, right, transverse, CCDS. An oval lymph node with the classical configuration of an inflammatory lymph node: clear “hilar sign,” strong hilar perfusion visible with sub-vessels branching in the periphery. Fig. 6.6 Transverse view of the right side of the neck at level II in a 6-year-old child, CCDS. An oval lymph node in acute lymphadenitis colli (RF). The node measures approximately 25 mm (to visually estimate the size the scale at the right-hand side of the image above the pictogram can be used). The central vascular structures can be seen branching out from the left upper side of the echogenic “hilar sign.” The perfusion is particularly intensive because the acuteness of the infective process and is consistent with the stage of disease. The facial artery (VA) appears at the right side of the image, the internal carotid artery (ACI) and external carotid artery (ACE) are to be found in level II below the lymph node. Fig. 6.7 Left side of the neck, transverse, level V, CCDS. A lymph node (see also Fig. 6.3) with strong hilar sign and hilar perfusion pattern. VJI, internal jugular; WS, vertebral spine; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Diagnosis: Sarcoidosis. Fig. 6.8 Left side of the neck, transverse, level II, CCDS. Two lymph nodes (RF and caliper marked) can be seen in level II: they are oval and well demarcated. A strong “hilar sign,” clearly defined margins and hilar perfusion, together with an L/S ratio > 2.0, indicate a reactive enlargement. ACI, internal carotid artery; ACE, external carotid artery; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Fig. 6.9 Left side of the neck, transverse, level V, CCDS. A round lymph node with ill-defined contours (asterisks) shows irregular vessel parts and pathways, totally unlike the normal central hilar perfusion pattern. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.10 Left side of the neck, longitudinal, level IV, CCDS. Two round metastases without a “hilar sign” (RF) and with subcapsular perfusion. Besides the inhomogeneous internal echoes, there is also a more hypoechoic central area. Cranially, the belly of the omohyoid muscle (asterisk) can be seen in cross-section, and the carotid bulb is visible at the left edge of the image, clearly placing the nodes in level IV. Fig. 6.11 Right side of the neck, level IV, split screen. Lying laterally to the internal jugular vein (VJI) is an enlarged oval, reactive lymph node; it has an L/S ratio of 2.0, is well demarcated, and shows the “hilar sign.” On the left of the image, another smaller lymph node with the same configuration can be seen medial to the vein. ACC, common carotid artery; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Diagnosis: Acute lymphadenitis. Fig. 6.12 Split screen, right side of the neck, level III. Lying between the internal jugular vein (VJI) and the common carotid artery (ACC) is an enlarged oval reactive lymph node; it has an L/S ratio of 2.0, is well demarcated, and shows the “hilar sign.” Fig. 6.13 Split screen, left side of the neck, level V, CCDS. An enlarged oval reactive lymph node; it has an L/S ratio of 2.0, is well demarcated, and shows both the “hilar sign” and hilar perfusion. MTRAP, trapezius muscle. Diagnosis: Toxoplasmosis. Fig. 6.14 Left side of the neck, transverse, level IV. A lymph node in level IV which, at first glance, appears oval and well demarcated. A polycyclic extension can be seen at the lateral end. This could be considered significant in a patient in whom malignancy is suspected, but the patient concerned had an acute respiratory tract infection. ACC, common carotid artery; MSCM, stemocleidomastod muscle; NV, vagus nerve; RF, lymph node; VJI, internal jugular vein; WS, vertebral spine. Fig. 6.15 Left side of the neck, transverse, level IV. A lymph node metastasis (RF) with an irregular rounded shape and clearly defined margins. The echogenicity is homogeneous. ACC, common carotid artery; VJI, internal jugular vein. Fig. 6.16 Split screen, right side of the neck, level IV. The lymph node is polycyclic in cross-section and lies directly on the internal jugular vein (VJI). To the right of the image is an oval, well-demarcated lymph node seen in longitudinal section, with a second, more rounded, lymph node lying cranially. No hilum can be distinguished in either the longitudinal or transverse section. ACC, common carotid artery. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.17 Floor of the mouth, transverse, level IA. Two round, space-occupying lesions (RF) with malignancy of the floor of the mouth. Besides the criterion of malignancy met in the ill-defined borders with the right digastric muscle (MD), both lymph nodes are round or polycyclic in shape. A further suspicious feature is the obvious inhomogeneity of the lymph node at the left edge of the image. MGH, geniohyoid muscle; MM, mylohyoid muscle. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.18 Left side of the neck, longitudinal. An oval, well-demarcated lymph node in level II, bordering the bed of the parotid gland (GP). The echogenic structure corresponds to a “hilar sign.” Cranial to the oval, lymph node is what appears to be a further rounded space-occupying lesion with central echogenic septa. This, however, is the digastric muscle (MD) seen in cross-section, which may be confused morphologically with a lymph node. More cranially, three lymph nodes can be identified in the apex of the echogenic lower pole of the parotid. Lymph nodes at the inferior border of the parotid gland that are simultaneously neighbouring the latero-posterior aspect of the submandibular gland are also called ”Küttner’s lymph nodes.” Diagnosis: Acute lymphadenitis of the neck and the parotid gland in viral infection. Fig. 6.19 Right side of the neck, level II/III. The space-occupying lesion with an inhomogeneous echo pattern lies on the external carotid artery (ACE) and internal carotid artery (ACI), medial to the internal jugular vein (VJI). Morphologically, a branchial cyst may appear similar, but would not show any intrinsic perfusion. MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.20 Split screen, right side of the neck, level IV, CCDS. The space-occupying lesion (RF) with an inhomogeneous echo pattern is sited laterally to the common carotid artery (ACC) and the internal jugular vein (VJI). The perfusion is peripheral and decentralized: in addition, irregular echogenic internal echoes are consistent with metastasis. MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.21 Split screen, right side of the neck, level III. A lymph node (RF) in a patient being followed up for malignant disease; the caudal margins show marked extension. Compared with the normal architecture, there is marked inhomogeneity. ACC, common carotid artery; VJI, internal jugular vein; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis recurrence, 6 months after initial multimodal treatment. Fig. 6.22 A schematic representation of morphological changes in metastases. These morphological transfornations within a lymph node illustrate sonographic findings of malignancy. Fig. 6.23 Left side of the neck, longitudinal, level III. A round lymph node metastasis with irregular borders has an anechoic center, which is indicative of necrosis caused by the metastatic transformation. VJI, internal jugular vein; MSCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle. Fig. 6.24 Left side of the neck, level II. Medial to the internal and external carotid arteries, the round metastasis has an anechoic center consistent with central necrosis; this is considered to be a sign of malignancy. To the left, medial in the image, is an ill-defined hypoechoic primary tumor (TU) of the left side of the oropharynx. The internal jugular vein (VJI) is compromised and can be seen between the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (MSCM) and the internal carotid artery (ACI). The vein can be demonstrated better with a Valsalva maneuver. ACE, external carotid artery. Fig. 6.25 Split screen, right side of the floor of the mouth. The two round paramedian lymph nodes with inhomogeneous internal echoes lie on the right in level IA. If there were an acute dental infection, these two lymph nodes (RF1 and RF2), both showing a weak “hilar sign” and clearly defined margins, would be consistent with reactive enlargement; however, both lymph nodes can definitely be considered possible metastases when there is clinical suspicion of cancer of the floor of the mouth, tongue, or sinonasal area. MD, digastric muscle; MGH, geniohyoid muscle; MM, mylohyoid muscle. Histological diagnosis: Lymph node metastasis. Fig. 6.26 Left side of the neck, transverse, level V. Multiple round supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes (RF) with a hypoechoic echotexture. The lymph nodes have ill-defined margins in part and no visible echogenic hilar structures. ACC, common carotid artery; MSCM, stermocleidomastoid muscle; VJI, internal jugular vein. Diagnosis: Metastases of small cell bronchial carcinoma.

Anatomy

Classification of the Cervical Lymph Nodes

Size and Three-dimensional Proportions

Echogenic Hilum (“Hilar Sign”) and Perfusion Pattern

Video 6.1).

Video 6.1).

Video 6.2).

Video 6.2).

Video 6.3).

Video 6.3).

Lymph Node Shape

Lymph Node Borders

Videos 6.4, 6.5). If a cervical lymph node is not clearly defined, it should first be considered whether the scanning conditions might be unfavorable.

Videos 6.4, 6.5). If a cervical lymph node is not clearly defined, it should first be considered whether the scanning conditions might be unfavorable.

Homogeneity of the intranodal Echotexture

Lymph Node Distribution

Level in the Neck

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine