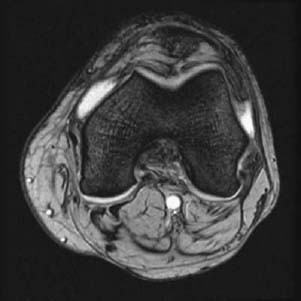

PART I Internal Joint Derangement Anthony G. Ryan and Peter L. Munk A 23-year-old man presented after a skiing injury with a painful knee that had swollen gradually over a period of hours since the injury. Clinical examination revealed an obvious effusion but no excessive motion (i.e., a negative drawer sign). Figure 1A Figure 1B Figure 1C MRI (Figs. 1A–1C) revealed a focal discontinuity of the cranial third of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Complete tear of the cranial third of the ACL. The typical pattern of injury (see below) is partially explained by the internal structure of the ligament. The distal attachment of the ligament is stronger than the proximal, having a broader base and an attachment to the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus in addition to the tibia. The ligament consists of two distinct components: anterior and posterior bands. The anterior band is stronger, containing more tightly packed fibers and thus conferring greater stability to the knee joint and resisting anterior tibial displacement. Although the fibers of the posterior band are packed less tightly, they remain taut in extension, thus resisting hyperextension. The classic mode of ACL injury is forced valgus strain on a fixed leg. It occurs in sports such as American football, soccer, and, less commonly, rugby. An almost equal and increasing incidence of ACL tears is seen in skiers, however, when the femur is forced into external rotation on a fixed tibia. In football players, the tear tends to occur in the midportion of the ligament, as a result of the direct impact and resultant “snapping”; in skiers, the ligament tends to tear proximally, as a result of the forced longitudinal strain. The typical pattern of ACL injury is that of an acute event, resulting in severe pain, an accompanying “snap,” and immediate disability. Delayed knee swelling is usual, with an immediate effusion more frequently seen in association with an intra-articular fracture. A hemarthrosis frequently accompanies complete ACL tears, but is seen less commonly with partial tears. Clinical examination is especially limited acutely, secondary to the associated pain and muscular spasm, with the anterior drawer and Lachman’s tests having sensitivities in the region of 78 to 89%, respectively. Arthroscopy, although clearly more accurate than physical exam, is invasive and expensive. False-negative arthroscopy may occur secondary to an obscuring infrapatellar plica, a partially healed torn ligament, or an intact synovial envelope (the ACL being intracapsular but extrasynovial). Knees with deficient ACLs are particularly susceptible to developing arthritis secondary to the increased translation of the femur on the tibia. In athletes, the resultant loss of strength and stability may be career-ending if the ligament is not repaired; even then, some professionals never return to their previous level of performance. If an associated fracture of the lateral tibial plateau is present (Segond fracture, Figs. 1D,1E), a “lateral capsular” sign may be present, whereby the bony fragment is seen projected adjacent to the lateral tibial plateau, which may be oriented in any direction, depending on the degree of hemarthrosis and so on that is present. The “deep lateral notch” sign (Figs. 1F,1G) is a notch produced in the lateral femoral condyle as a result of impaction of the condyle against the posterolateral tibial plateau. There may be an associated fracture of the tibial plateau.

CASE 1

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Clinical Findings

Complications

Imaging Findings

RADIOGRAPHY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree