10 Carpal Ligaments

The carpal ligaments guarantee stability of the carpal joints while allowing considerable freedom of movement in these joints of complex construction. The interosseous and extrinsic ligaments, the proximal and the distal V-shaped ligaments on the palmar aspect, and the dorsal V-shaped ligaments can be distinguished from each other by their course. The scapholunate and the lunotriquetral ligaments play an important role in carpal stability. For imaging of the carpal ligaments, radiographic arthrography preferably combined with CT or MRI, different types of MRI sequences, and arthroscopy are available. The diagnostic value of these procedures differs according to the individual ligaments.

Fundamental Anatomy

Most of the carpal ligaments have an intracapsular course, but only a few reinforce the joint capsule. The palmar ligaments are thicker and functionally more important than the dorsal ligaments because of their stabilizing function. Carpal ligaments are classified in terms of their complex anatomic arrangement. The following description is based primarily on the functional V-shaped ligamentary system, which has been modified according to new information gained from MRI imaging ( Table 10.1 ).

The individual ligaments in this group are listed in Table 10.2 . Their names derive from their origins and attachments, as well as from their directions.

There are discrepancies in the literature regarding the precisely anatomically defined collateral ligaments. Since such ligaments, if they were robustly constructed, would restrict multiaxial movement in the wrist, only thin collateral supportive ligaments are found on the joint capsule. Nevertheless, the collateral ligaments in the wrist are listed in Table 10.1 .

Interosseous Ligaments

Some of these ligaments have a membranous attachment to the articular cartilage, and some cross the cartilage and insert directly onto the bone as Sharpey’s fibers. The interosseous ligaments run in two directions, either taking a longitudinal course between the radius and the scaphoid and lunate or running transversely between the two carpal rows ( Fig. 10.1 ). The interosseous ligaments are the most important stabilizers of the carpus (unit of rotational stability).

Radioscapholunate (RSL) Ligament, Radioscaphoid(RS) Ligament, and Radiolunate (RL) Ligament

Current option is that the RSL ligament (Testut’s ligament), aside from stabilizing the proximal pole of the scaphoid, functions above all as a neurovascular bundle. The terminal branch of the anterior interosseous artery and a fiber from the anterior interosseous nerve are in this ligament. Both supply the scapholunate ligament and the proximal pole of the scaphoid. The RSL ligament originates at the palmar rim of the radius at the level of the interfacet prominence and extends with two fascicles to the palmar and middle sections of the scapholunate ligament. The RSL ligament lies between the extrinsic RLT ligament in the palmar direction and the intrinsic SL ligament dorsally.

The radioscaphoid and the radiolunate (“short radiolunate”) ligaments are not independent ligaments but delineated fascicles reinforcing the palmar joint capsule.

Topographically they are located on the radial and ulnar sides of the RSL ligament. The radiolunate ligament stabilizes the lunate in its course to the anterior horn, and the radioscaphoid ligament prevents the scaphoid from drifting dorsally.

The interosseous ligaments of the proximal carpal row are clinically more important than those of the distal row.

Scapholunate Ligament (SLL)

This very important ligament not only ensures close association between the scaphoid and lunate, but is also the most important stabilizer of the carpus. The SLL extends between the proximal borders of the scaphoid and the lunate. Because of the different joint circumferences of the scaphoid and the lunate as well as a certain intrinsic elasticity of the ligament, a relative rotational movement is possible between the scaphoid and lunate during flexion and extension. In the sagittal plane, the ligament stretches in a horseshoe shape at a depth of 13 mm and has an average total length of 18 mm ( Fig. 10.2 ). The SLL terminates distally with loose ends. Histologically, the SLL has three different segments with different biomechanical functions:

The palmar segment extends in a slightly oblique-transverse direction in the coronal plane. It consists of thick collagen fibers embedded in loose connective tissue and inserts directly into the cortical bone. This segment is longer than the other two. Because of this constellation, a slight movement between the scaphoid and the lunate is possible at the level of the palmar ligamentary segment. The palmar segment of this ligament is, like the radioscapholunate ligament which inserts here, surrounded by small blood vessels and nerve fibers and is relatively well vascularized.

The middle segment of the SLL, which extends in the transverse plane, is a thin, fibrocartilaginous membrane without any stabilizing function. It extends between the articular cartilages of the scaphoid and the lunate. The middle, membranous third of the SL ligament is predisposed to degenerative perforations, which can regularly be found here from the 30th year of life and are referred to as “pinhole” defects. They are usually asymptomatic. During arthrography they can permit intercompartmental passage of contrast medium despite the absence of a scapholunate dissociation

The dorsal section, which can also be best seen in the coronal plane, comprises of thick, closely packed collagenous fibers running transversely. The major portion of these fibers insert via Sharpey’s fibers into cortical bone. The dorsal segment is surrounded by ultrafine blood vessels and nerve fibers. The thicker and relatively shorter dorsal section of the ligament ensures the actual stability of the scapholunate connection. Usually a traumatic injury (rarely a degenerative lesion) of the dorsal segment of the SLL causes rotation-subluxation of the scaphoid and scapholunate dissociation.

Lunotriquetral Ligament (LTL)

The lunotriquetral ligament is similar in construction to the SL ligament, but is thinner. As a tight ligament, it allows only a slight displacement between the lunate and the triquetrum from proximal to distal. The LTL is Ushaped. It consists of thinner dorsal and strong palmar fascicles that extend proximally in the coronal plane between the borders of the lunate and the triquetrum. The palmar segments of the ligament ensure functional stability between the two bones. They are supported by the palmar radiolunotriquetral ligament and the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament. The middle section of the LTL, which extends horizontally as a thin membrane, has no stabilizing function whatsoever. It is a preferred site for degenerative perforations.

Capitohamate Ligament (CHL)

Thick interosseous ligaments of no particular clinical importance run between the bones in the distal carpal row. In MRI, the very stable CHL appears as a hypointense structure between the capitate and the hamate.

Palmar V-shaped Ligaments

The palmar V-shaped ligaments are thicker than the dorsal ligaments. Within a complex anatomic arrangement, two V-shaped groups with the following ligaments can be differentiated according to functional aspects:

Ligaments of the palmar proximal “V”: radiolunotriquetral ligament (RLTL), ulnolunate ligament(ULL),and ulnotriquetralligament (UTL)

Ligaments of the palmar distal “V”: radioscaphocapitate (RSCL) and arcuate (TCSL) ligaments Poirier’s space, an area largely free of ligaments, lies between the two groups of V-shaped ligaments on the palmar aspect at the level of the lunocapitate joint. Topographically, a row of ligaments on the radial side and another row on the ulnar side consist of:

Ligaments on the radial side: radioscaphocapitate ligament (RSCL) and radiolunotriquetral ligament (RLTL)

Ligaments on the ulnar side: ulnotriquetral ligament (UTL), ulnolunate ligament (ULL), and arcuate ligament (TCSL)

The interosseous ligaments that are located furthest proximal (radioscapholunate ligament, radioscaphoid ligament, and radiolunate ligament) also lie on the palmar side. The carpal ligaments are described below according to the functionally oriented “concept of Vshaped ligaments.”

Ligaments of the “Proximal V”

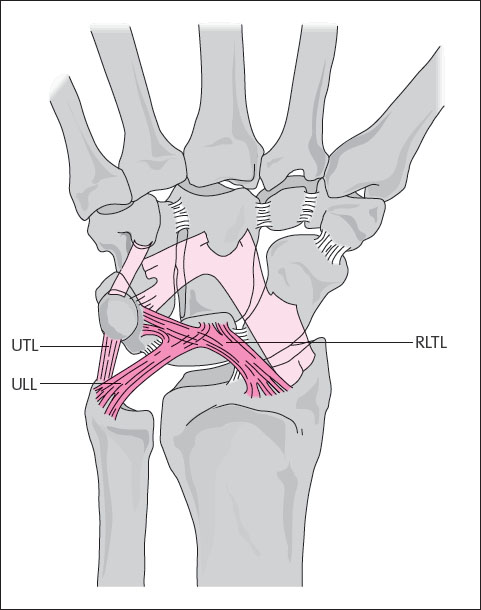

The function of the proximal set of ligaments with the radius and ulna functioning as the base and the lunate as the apex ( Fig. 10.3 ) is in the longitudinal transference of force between the ulna and the carpus and fixation of the proximal carpal row, especially the lunate as the intermediate element of movement (so-called “intercalated segment”).

Radiolunotriquetral Ligament (RLTL)

The radiolunotriquetral ligament (also called the “long radiolunate ligament”) makes up the radial leg of the V and is the strongest carpal ligament. It originates with a broad base on the palmar rim of the radius and lies in ulnar and proximal proximity to the RSCL. It follows a relatively level course first to the lunate, where it attaches to its anterior horn with a few fibers, and continues in the same direction with thicker fascicles to terminate in apalmar trough on the triquetrum ( Fig. 10.3 ). Together with its dorsal “partner” ligament, the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament (DRTL), the RLTL performs the important function of preventing the carpus from slipping along the joint surface of the radius, which has a 25° inclination to the ulnar aspect. Because of their alignment with the ulnar inclination of the radial joint surface and their function of keeping the carpus in a stable position, the RLTL and DRTLligaments are also known as the “extra-articular slingshot.”

Ulnolunate Ligament (ULL) and Ulnotriquetral Ligament (UTL)

The ulnar leg of the proximal V consists of the palmar ligamentary structures of the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), i.e., the ulnolunate and the ulnotriquetral ligaments ( Fig. 10.3 ). Both ulnocarpal ligaments are located on the palmar aspect and fortify the triangular fibrocartilage complex. They originate on the palmar radioulnar ligament and proceed to the anterior horn of the lunate or to a depression on the palmar side of the triquetrum. Ligament fibers often radiate into the lunotriquetral ligament. The ULL and UTL are important stabilizers of the ulnar side of the carpus and prevent nondissociative forms of instability.

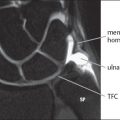

Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC)

Aside from the ULL and the UTL, the triangular fibrocartilage complex also consists of the following elements: the triangular fibrocartilage (TFC), the palmar and dorsal radioulnar ligaments, the meniscus homologue, the tendon sheath of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) muscle, and the ulnar collateral ligament. For details, see Chapter 11.

Ligaments of the “Distal V”

The palmar distal V-shaped ligaments have an important function in stabilizing the midcarpal joint and in preventing the scaphoid from its tendency to rotate in a flexed position ( Fig. 10.4 ).

Radioscaphocapitate Ligament (RSCL) and Scaphocapitate Ligament (SCL)

The radial side of the distal group of V-shaped ligaments consists of the radioscaphocapitate and the scaphocapitate ligament segments, which run in the same direction rection ( Fig. 10.4 ). These sections lie distal to the RLTL. The RSCL originates with abroad base at the styloid process of the radius and extends in a diagonal direction on the palmar side first through the groove in the middle third of the scaphoid (“scaphoid waist”), from which it is separated by a synovial duplication. It then continues diagonally to insert on the palmar aspectof the middle part of the capitate. The distal half of the RSCL is accompanied by the SCL, which also connects the middle third of the scaphoid with the capitate. The ligamentary insertion prevents the capitate from drifting to the ulnar side. The RSCL keeps the scaphoid, which is aligned in a palmar direction, in a stable position and prevents it from tipping further toward the palmar aspect (“palmar support ligament”). If the scaphoid is fractured in the proximal half, the RSCL can fold into the fracture gap and lead to scaphoid nonunion.

Scaphotrapeziotrapezoid Ligament (STTL)

In a wider sense of the term, the STTL must also be counted as a radial-distal leg of the V-shaped system of ligaments. These are intrinsic ligaments located on the palmar and dorsal sides that connect the scaphoid with the trapezium and the trapezoid as a “radial link” and permit only moderate movement among these three carpal bones.

Arcuate (Triquetrocapitoscaphoid) Ligament (TCSL)

The ulnar side of the distal group of V-shaped ligaments is formed by a ligament with an arching course, the arcuate ligament (so-called “delta ligament”). Because of its triquetrocapitoscaphoid course deep in the carpal tunnel, it will hereafter be referred to by the acronym TCSL. The ligament originates on the palmar side of the triquetrum, extends in a bow shape over the tip of the hamate and the neck of the capitate, and terminates on the palmar side of the distal third of the scaphoid ( Fig. 10.4 ). As a fairly loose ligamentary connection in the “ulnar link,” the TCSL permits the triquetrum to slide a considerable distance over the spiral-shaped joint surface of the hamate. This explains the “high” and “low” triquetral positions during radial and ulnar inclination. The rest of the TCSL is tighter and prevents palmar flexion of the proximal carpal row.

The space between the proximal and distal fascicles of the palmar V-shaped ligamentary system at the level of the capitatolunate joint (Poirier’s space) has no ligaments and is filled with synovial tissue. The lack of a palmar lunocapitate ligament predisposes this space to become a “site of less resistance” in hyperextension traumas and explains the tendency of the lunate to dislocate to the palmar side in perilunate and lunate dislocations.

Ligaments of the “Dorsal V”

Although the dorsal ligaments ( Fig. 10.5 ) are weaker than those on the palmar side, they are important biomechanically. Through their convergence at the triquetrum, the dorsal ligaments, together with the RLTL on the palmar side, which extends in the same direction, prevent the carpus from sliding along the radial joint surface, which slopes to the ulnar side (so-called “slingshot” ligaments). Since both dorsal ligaments cover the middle carpal column, the lunate is stabilized by the dorsal radiotriquetral ligament, and the capitate is stabilized from the dorsal side by the intercarpal ligament and held in colinear alignment. Two ligaments can be delineated from the dorsal joint capsule, which they fortify.

Dorsal Radiotriquetral Ligament (DRTL)

The extrinsic dorsal radiotriquetral ligament extends from the dorsal rim of the radius diagonally to the dorsal side of the triquetrum ( Fig. 10.5 ). In its course, it crosses the proximal scaphoid pole and the posterior horn of the lunate, near which the dorsal segments of the intrinsic SLL and LTL are closely associated with the DRTL. As a rule, this ligament originates on Lister’s tubercle of the radius. Accessory fascicles can, however, also originate from the styloid process of the radius or, further toward the ulnar aspect, from the dorsal rim of the radius.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree