Midsagittal T1WI through the corpus callosum.

Photograph of the back showing hyperpigmented skin lesions.

Incontinentia Pigmenti

Primary Diagnosis

Incontinentia pigmenti

Differential Diagnoses

Sequelae of neonatal HSV encephalitis

Hypoxic ischemic injury

Imaging Findings

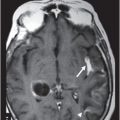

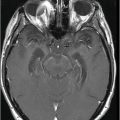

Fig. 120.1: (A–B) Axial T2WI and Fig. 120.2: Axial FLAIR through the body of lateral ventricles showed extensive asymmetric encephalomalacic changes, predominantly involving the left periventricular region with CSF-filled cavity changes in the subcortical white matter. Fig. 120.3: Sagittal T1WI of the corpus callosum showed hypoplasia. Fig. 120.4: Swirling hyperpigmented lesions following the lines of Blaschko are noted along the anterior abdominal wall and groin (arrows). Fig. 120.5: Picture of the back and Fig. 120.6: Picture of the lower extremities showing similar hyperpigmented lesions.

Discussion

In a female with a history of neonatal onset of seizures, negative CSF analysis for HSV infection, and lack of hypoxic injury, the presence of hyperpigmented skin lesions along the lines of Blaschko and MR imaging showing features of periventricular leukomalacia and white matter changes suggests a diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti. Sequelae of neonatal fulminant HSV encephalitis and hypoxic ischemic injury can have similar imaging appearances but negative CSF analysis and lack of hypoxic ischemic injury exclude these entities.

Incontinentia pigmenti, also known as Bloch-Siemens syndrome, Bloch-Sulzberger disease, or melanoblastosis cutis, is a rare X-linked neurocutaneous syndrome, usually affecting females, while often lethal in utero to males. Ectodermal tissues including the skin, eyes, teeth, and central nervous system are primarily affected. The diagnosis is clinical, with pathognomonic skin manifestations, namely cutaneous vesicular eruptions, along the lines of Blaschko, usually evident by the first to second week of life. Skin lesions evolve through four stages: 1) blistering (birth to four months of age); 2) wart-like rash (for several months); 3) swirling macular hyperpigmentation (six months of age to adulthood); 4) linear hypopigmentation. Central nervous system findings including seizures, psychomotor retardation, spasticity, or paralysis have been reported in 30–50% of cases.

The disease is X-linked dominant, with mutations of the IKBKG gene, which regulates nuclear factor kappa B, a group of proteins essential for preventing apoptosis. Similar changes have been attributed to the NEMO gene (NF-kappa-B essential modulator) located on Xq28. The mutation can be sporadic (type I) or transmitted (type II). The typical phenotype results from functional mosaicism, a consequence of lyonization.

Neuroimaging findings are variable, but usually support the clinical evolution of the disease. In the neonatal period, acute cortical necrosis and subcortical hemorrhages are seen. In older children, manifestations include periventricular leukomalacia, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, encephalomalacia, multiple cerebral infarction, and retinal vascular abnormalities. Intracranial vascular abnormalities ranging from occlusion and narrowing and impaired filling, to branching have been described in the literature. Sequelae of neonatal fulminant HSV encephalitis and hypoxic ischemic injury can have similar imaging appearances but negative CSF analysis and lack of hypoxic ischemic injury help exclude these entities.

Diagnosis of incontinentia pigmenti is ultimately distinguished from other diagnostic considerations by a physical examination, revealing the characteristic skin rash. Thus, consider incontinentia pigmenti in patients presenting with a skin rash accompanied by non-specific neurologic symptoms. Acutely, neuroimaging reveals cortical necrosis and subcortical hemorrhages in the infantile stage, with a wide range of non-specific chronic findings in later childhood and early adulthood.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree