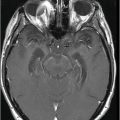

Axial T2WI through the orbit.

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension

Primary Diagnosis

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Differential Diagnoses

Secondary intracranial hypertension

Treatment with vitamin A, tetracycline, or lithium

Steroid withdrawal

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Imaging Findings

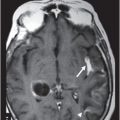

Fig. 125.1: Axial T2WI through the orbit demonstrated flattening of the posterior sclera (arrow). Fig. 125.2: Axial fat-suppressed T1WI through the orbit demonstrated flattening of the posterior sclera and inversion of the left optic nerve head (arrow). Fig. 125.3: Coronal STIR image through the orbits, posterior to the globe, demonstrated optic nerve sheath dilation with prominent CSF around the optic nerves and hydrops (arrows). Fig. 125.4: Midline sagittal T1WI demonstrated empty sella (arrow). Fig. 125.5: Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image of the phase contrast MR venogram demonstrates gradual tapering of the left transverse sinus (arrows).

Discussion

The presence of a long-standing headache, with visual symptoms, in an obese female patient of childbearing age is highly suspicious of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). A constellation of imaging findings including a flattening of the posterior sclera, inversion of the optic nerve head, dilation of the intraorbital optic nerve sheath, and an empty sella are diagnostic of IIH. These findings are also frequently associated with gradual tapering of one of the transverse sinuses (the left, in our patient).

The lack of intracranial mass, or other causes of secondary increased intracranial pressure (ICP) seen on imaging, rules out secondary IIH. The absence of prior drug treatment rules out the possibility of drug-related causes for the increased ICP.

Also known as pseudotumor cerebri, IIH is a rare condition (reported annual incidence of 1–2 per 100,000) characterized by presence of an increased ICP in the absence of underlying brain pathology. It is a disease of both pediatric and adult populations, but a female predominance of 9:1 is seen only in adults. Familial occurrences have been reported without clear genetic relationships. Patients present with headache, papilledema, and normal CSF composition, but with elevated CSF pressure. No focal neurologic deficits are seen.

Several inconclusively proven causal mechanisms related to altered CSF dynamics have been proposed. The important etiologies include obesity, delayed CSF absorption, and venous outflow abnormality with increased cerebral venous pressure. The proposed pathophysiologic rationales for association with obesity include increased intrathoracic and abdominal pressure, increased central venous pressure and increased ICP, or a hormonal mechanism. There is some convincing evidence of increased resistance to CSF flow, but it is unclear if it is due to decreased CSF absorption or decreased intracranial compliance. Stenotic transverse sinuses have been observed in a large number of IIH patients. Venous stenosis is likely a result of raised ICP. Alternatively, venous sinus stenosis may be primary and increases venous pressure with resultant intracranial hypertension.

Typically, an IIH patient is an obese female of childbearing age who presents with headache, diplopia, visual loss, and papilledema without focal deficits, except VI nerve palsy. The headache may be throbbing or pressure-like, unilateral or holocephalic, and exaggerated by activities increasing ICP, e.g., Valsalva, coughing, or bending over. Long-standing papilledema may produce optic atrophy wherein the disk is viewed as pale, gliotic, and flat. Visual field deficits occur in up to 90% with blind spot enlargement and even transient visual loss. Risk of blindness is 4–10%. There may be occasional pituitary dysfunction. Unilateral or bilateral tinnitus has been reported, which could be due to increased CSF pulsations and venous sinus turbulence.

Imaging may be completely normal with elevated ICP. Typical imaging findings of IIH include flattening of the posterior sclera, intraocular protrusion of the optic nerve head (reversal of the optic nerve head), distension of the optic nerve sheath (more than 2 mm), vertical tortuosity of the orbital optic nerve, enhancement of the optic nerve head, empty sella turcica, and deformity of the pituitary gland (attributed to chronic pituitary gland compression, and bone remodeling by CSF pulsations). Less commonly, slit-like ventricles are also seen. These changes are reversible on reduction of the ICP. Posterior globe flattening, optic nerve protrusion, and slit-like ventricles have been shown to have high specificity, but none of these signs is highly sensitive.

Other findings of IIH include altered flow velocity in the venous sinuses and narrowing of the sinuses. It is not established if the stenosis is the cause of IIH or the effect. If a pressure gradient is present across the dural venous sinus stenosis, stenting of the sinus may be offered as treatment with varying results.

The diagnosis is confirmed in presence of elevated ICP of > 25 cm H2O with lumbar puncture in lateral decubitus position without sedation. Normal adult ICP is defined as 7.5–20 cm H2O, with values of 20–30 cm H2O representing mild intracranial hypertension. Intracranial pressure values greater than 20–25 cm H2O mostly require treatment and sustained ICP values of greater than 40 cm H2O represent severe, life-threatening intracranial hypertension.

Management depends on the signs and symptoms, and treatment strategies vary. Conservative management includes weight loss, acetazolamide, and diuretics such as furosemide. Lumbar puncture and CSF drainage may provide symptom relief lasting several weeks. Surgical intervention with CSF shunting is indicated in patients with visual loss or impending visual loss in patients not responding to medication therapy. Optic nerve sheath fenestration is used to relieve papilledema transiently.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree