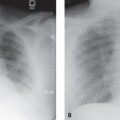

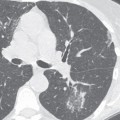

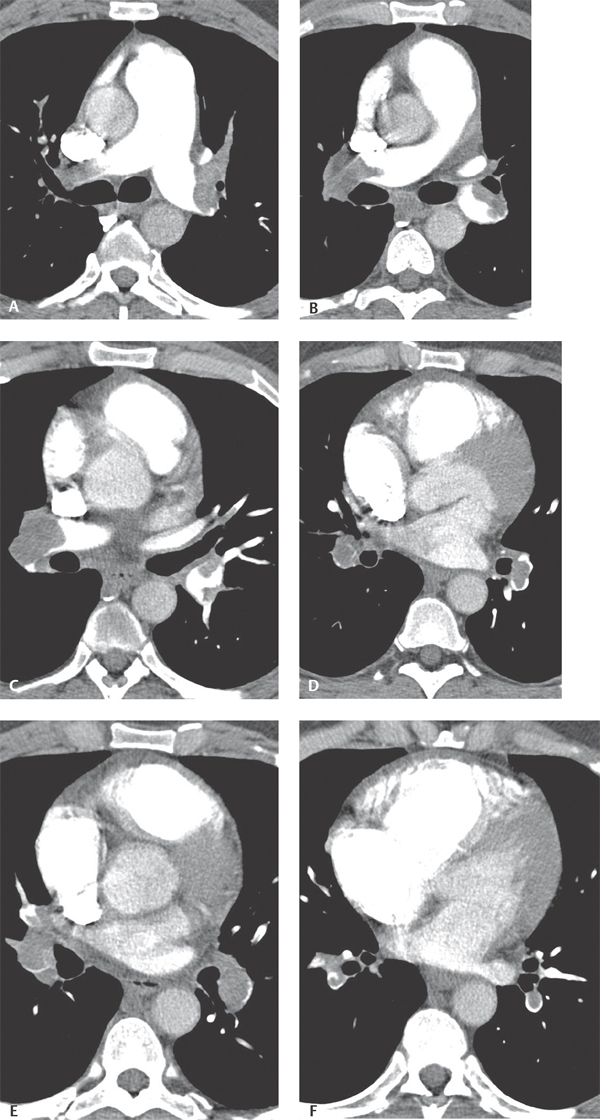

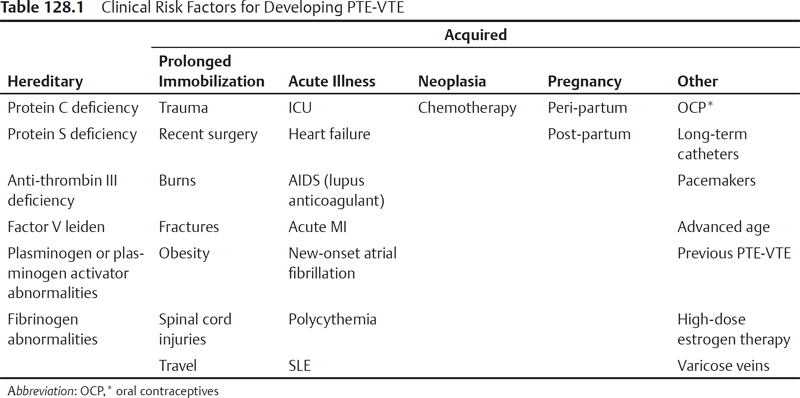

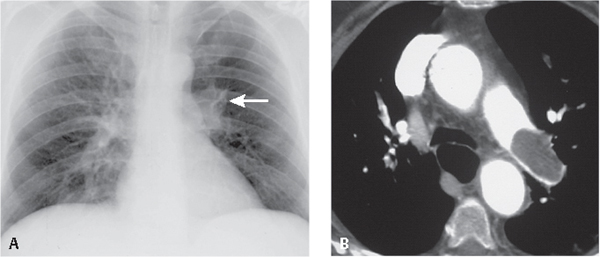

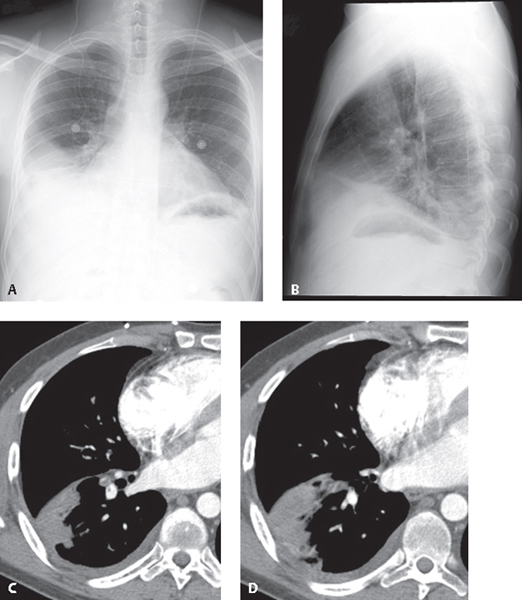

CASE 128 44-year-old man presenting to the emergency department following an 18-hour transcontinental air flight with chest pain and shortness of breath Chest CTPA (mediastinal window) (Figs. 128.1A, 128.1B, 128.1C, 128.1D, 128.1E, 128.1F) demonstrates extensive filling defects involving virtually every branch of the pulmonary arterial circuit. The right heart, and right ventricle in particular, is enlarged and there is inward bowing of the interventricular septum consistent with right heart strain. Acute Pulmonary Thromboembolic Disease None Acute pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) is responsible for 2–7% of acute care hospital deaths, and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death, after myocardial ischemia and stroke. However, PTE is not a disease in and of itself but a complication of underlying venous thrombosis (VTE). The average annual incidence of VTE is 1 per 1,000 (United States), with approximately 250,000 incident cases occurring annually. Autopsy studies show an equal number of patients with PTE-VTE unsuspected or not diagnosed antemortem. Thus, an estimated 650,000 to 900,000 cases of fatal and nonfatal PTE-VTE occur annually in the United States alone. Normally in the venous system there is a dynamic balance between the formation and subsequent lysis of microthrombi that allows for local hemostasis in response to injury but prevents uncontrolled propagation of thrombus. Certain pathologic conditions allow microthrombi to escape the fibrinolytic system, propagate, and potentially embolize into the pulmonary arterial circuit as pulmonary emboli. Ninety percent of such pulmonary emboli originate from lower extremity deep veins. Predisposing VTE is induced by inflammation of the vessel wall, venous stasis, and hypercoagulable states (i.e., Virchow triad). Clinical risk factors for PTEVTE are directly related to one or more of these components and are summarized in Table 128.1. Diagnosis of PTE poses a challenge for both clinicians and radiologists because the signs and symptoms are nonspecific. The classic triad of pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis is neither sensitive nor specific and occurs in less than 20% of patients. Additionally, many patients are relatively asymptomatic. Physical signs may include tachypnea; rales, pleural rub, or new wheezing; tachycardia; S3 or S4 gallop; new murmur; accentuated second heart sound; fever; diaphoresis; lower extremity edema; and cyanosis. Massive pulmonary embolism may be associated with hypotension due to acute cor pulmonale. Patients with PTE may have an abnormally high A-a gradient, and right ventricular strain on ECG. D-dimer levels may be elevated with PTE-VTE. D-dimer is a degradation product of plasmin-mediated proteolysis of cross-linked fibrin and is considered positive when >500 ng/mL. However, levels may be falsely elevated in numerous clinical settings (e.g., severe trauma, recent surgery, infection, neoplasia, rheumatoid factor, and advanced age). Fig. 128.1 • Primary role: exclude other causes of a particular patient’s signs and symptoms; guide V/Q scan interpretation • 10–15% of symptomatic patients with angiographically proven PTE—normal chest X-ray • Over 24–72 hours, initially normal chest radiograph may begin to demonstrate atelectasis, small pleural effusion, and ipsilateral diaphragmatic elevation • After 24–72 hours, one-third of patients with proven PTE develop focal air space opacities indistinguishable from pneumonia • Peripheral oligemia (i.e., Westermark sign) (Fig. 128.2A) • Enlargement of a major pulmonary artery (i.e., Fleischner sign) (Fig. 128.2A) • Abrupt tapering of the occluded vessel (i.e., knuckle sign) • Volume loss and ipsilateral diaphragmatic elevation • Cardiac enlargement • 15% of acute PTE—complicated by pulmonary infarction • Any of the above signs and peripheral parenchymal consolidation (i.e., Hampton hump) (Figs. 128.3A, 128.3B) • Early infarcts Fig. 128.2 PA chest radiograph (A) of a 46-year-old man complaining of chest pain shows preserved lung volumes, a hyperlucent left hemithorax, a disproportionately enlarged left pulmonary artery (Fleischner sign), and diffuse oligemia of the ipsilateral thorax (Westermark sign). Contrast-enhanced chest CT (mediastinal window) (B) reveals a large soft-tissue attenuation acute PTE occluding and expanding the left pulmonary artery. (Images courtesy of Laura E. Heyneman, MD, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, North Carolina.) Fig. 128.3 PA (A) and lateral (B)

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Clinical Findings

Imaging Findings

Chest Radiography

Chest Radiography: Thromboembolism without Infarction

Chest Radiography: Thromboembolism with Hemorrhage or Infarction

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree