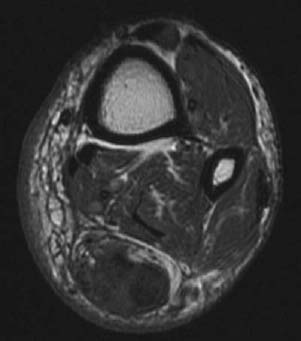

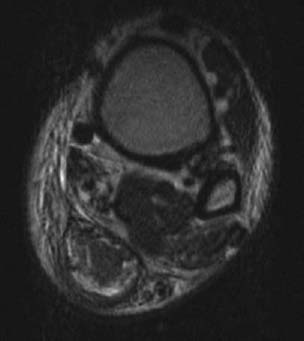

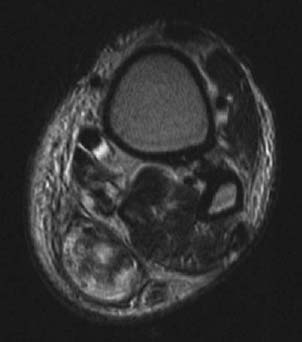

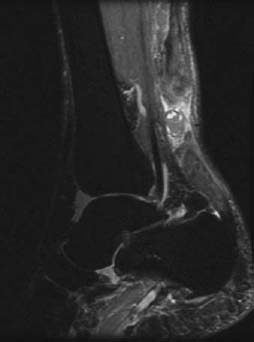

CASE 21 Anthony G. Ryan and Peter L. Munk A 41-year-old man heard a snapping sound in his ankle while stretching for a lob shot during a tennis game. He developed an immediate painful limp with reduced plantar flexion. Squeezing his calf musculature while in the prone position (the Thompson test) did not produce the expected plantar flexion. Direct questioning revealed a long history of intermittent pain and discomfort at the back of his ankle. Figure 21A Figure 21B Figure 21C Figure 21D An axial T1-weighted image (Fig. 21A) shows dramatic thickening of the Achilles’ tendon close to its calcaneal insertion. There is heterogeneous intratendinous signal consistent with internal architectural disorganization. An axial T2-weighted image (Fig. 21B) shows heterogeneous intrasubstance signal, again consistent with internal architectural disorganization. High signal intensity material is shown surrounding the tendon consistent with either edema or hemorrhage. An axial T2-weighted image (Fig. 21C), adjacent to Fig. 21B, shows heterogeneous, high signal intensity contained within the paratenon with no definite tendon identified: the “absent tendon” sign. A sagittal STIR (Fig. 21D) shows a complete tear of the tendon with laxity of each torn end, intervening high signal intensity consistent with edema and/or hemorrhage. The tendon on either side of the tear is markedly abnormal, being thickened with heterogeneous internal signal consistent with chronic tendinosis ± chronic partial tear. Torn Achilles’ tendon on a background of chronic tendinitis. None—the appearance is pathognomonic. Although the Achilles’ is the thickest and strongest tendon in the body, it is also the most frequently injured. Formed by the coalescence of the gastrocnemius and soleus, the tendon measures approximately 10 to 15 cm in length and has an anteroposterior (AP) diameter of 7 mm or less in men and less than 6 mm in women. In cross section, the anterior border of the tendon should be concave and parallel the posterior border, except immediately above the calcaneal insertion, where it becomes elliptiform. The tendon is surrounded by a thin film of connective tissue, the paratenon, which, in addition to lubricating the tendon’s motion, serves as a source of auxiliary blood supply. Despite this, the supply to the Achilles’ tendon remains relatively deficient between 2 to 6 cm proximal to its calcaneal insertion, resulting in a zone of vulnerability. There is a fat pad anterior to the tendon, eponymously known as Kager’s fat pad. There are two bursae in relation to the tendon: a retrocalcaneal bursa, anterior to the tendon at the level of the insertion, and a retrotendo-Achilles’ bursa, which is an acquired bursa between the tendon and skin at the level of the insertion. This condition is typically secondary either to acute trauma, including severe strain and penetrating injuries, or to overuse in athletes or the elderly (degenerative tendinopathy). Male long-distance runners are particularly susceptible. Rupture may be spontaneous or secondary to acute trauma (sudden excess tensile force or laceration) or chronic trauma (overuse resulting in repeated microtrauma), leading, over time, to degenerative tendinosis. The coalescence of foci of mucoid degeneration can lead to interstitial tears, gross partial tears, and eventually complete rupture. Spontaneous ruptures occur in those patients with underlying systemic illnesses predisposing to tendinopathy: It has been calculated that stretching a tendon to between 4 and 8% of its original length causes irreversible disruption of the collagen cross-link structures. This is potentially reparable, unless the inciting activity is continued.

Achilles Tendon Tear

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Findings

Stages of Disease

Complications

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree