22 Carpal Dislocations and Fracture-Dislocations

Carpal dislocations can involve one or more carpal bones and are often combined with fractures. They are classified as (1) perilunate and lunate dislocations, in which a stage IV of lunate dislocation corresponds with perilunate dislocation; (2) perilunate fracture-dislocation; (3) scaphoid-capitate fracture syndrome; and (4) axial dislocations. Perilunate injuries involve almost exclusively dorsal forms of dislocation. The palmar variants are very rare. For recognition of the entire trauma extent, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are often necessary, in addition to precisely positioned radiographs in two planes. CT helps to determine the exact extent of the fractures and dislocations, and MRI visualizes the causative ligament lesions, possible osteonecrosis, and damage to the articular cartilage.

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

A typical dislocation injury of the wrist is the perilunate dislocation, which leads to a dissociation of the lunate and the head of the capitate within the “vulnerable zone” of the midcarpal joint. In perilunate dislocations, the patient often cannot recall the exact mechanism of injury. In experiments, perilunate injuries were caused by hyperextension, ulnar inclination, and intracarpal supination. Axial compression caused by falls associated with high-velocity accidents, in which a handlebar or steering wheel is grasped during the impact, can be responsible for such injuries. The radioscaphocapitate ligament is torn, the radial styloid process is fractured, or the intrinsic ligaments of the proximal carpal row are torn, with the scapholunate ligament being ruptured first and then the lunotriquetral ligament. Basically, dislocation lines along the lesser arc (lesser-arc injury) are differentiated from those along the greater arc (greater-arc injury) affecting the scaphoid, capitate, and sometimes even the triquetrum ( Fig. 22.1 ).

A carpal dislocation injury usually leads to a visible deformation of the wrist with restricted and painful active movement. Neurological deficits within the innervation zone of the median nerve can occur as a result of displacement of the lunate into the carpal tunnel. Irritations of the ulnar nerve can be caused by fractures and dislocations of the hamate, triquetrum, and pisiform.

Perilunate and lunate dislocations:

|

Perilunate and lunate fracture-dislocations:

|

Scaphoidcapitate fracture syndrome:

|

Axial dislocations/fracture-dislocations:

|

Classification

Injuries of the lesser arc are perilunate ligament tears without fractures in the carpus. Injuries of the greater arc are carpal fracture-dislocations. Fractures occurring within the perilunate greater-arc mechanism affect the radial and ulnar styloid processes, the scaphoid, the triquetrum, the capitate, and the hamate. Although an isolated fracture of the radial styloid process occurs usually without a perilunate injury, a perilunate dislocation should be excluded when such an injury of the radius has been identified. Accompanying dislocations of the head of the radius or of the elbow are also possible in perilunate dislocations in the proximal forearm. A perilunate dislocation with scaphoid fracture is known as a transscaphoid perilunate fracture dislocation (de Quervain). The direction of the dislocation should always be indicated. The distal forearm is the reference according to which a dislocation is described as dorsal or palmar ( Table 21.1 ). The commonest injury to the greater arc is the dorsal transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocation.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography

Standardized views of the carpus in dorsopalmar and strictly lateral beam projection (so-called neutral position, see Chapter 1) provide the basis for diagnosis of carpal dislocation injuries. Both planes must be centered on the radiocarpal joint. This requirement can be met with the help of a positioning block. With a correct positioning method, the following criteria apply to the normal radiographic anatomy of the wrist (Chapter 12):

In the dorsopalmar view, Gilula’s three carpal lines can be drawn without steps. The lunate has a trapezoid shape.

In the lateral view, the radius and the ulna overlap. A continuous line connects the radius, the lunate, the capitate, and metacarpal III (colinear configuration).

Perilunate dislocations of the carpus can be confusing in the survey radiographs, especially when they are combined with fractures ( Fig. 22.2 ). In general, the radiographic signs listed in Table 22.2 are considered characteristic.

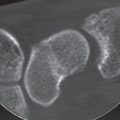

Computed Tomography

High-resolution, multislice spiral CT enables not only exact visualization of the extent of the dislocation and/or fracture without overlap but also the detection of occult fractures that were not seen in the survey radiographs. In the two-dimensional (2D) multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) technique, other planes are depicted without relevant loss of image quality. Three-dimensional (3D) post-processing procedures, like the surface-shaded display (SSD) and the volume-rendering (VR) methods, can accurately demonstrate even complex dislocations. Multislice CT is, therefore, always indicated whenever there is a complex carpal trauma.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Whereas CT offers advantages in the diagnosis of carpal fractures, MRI presents the following possibilities:

Radiographically occult fractures and bone-marrow contusions (so-called “bone bruises”) can be identified.

Direct visualization of injuries to the capsuloligamentous complex and the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC). Reparative vascularization processes occur at the injured ligaments, which can be demonstrated with contrast-enhanced MRI. In particular, fat-suppressed T1-weighted sequences sensitively identify these focal spots of increased enhancement, which must, however, be differentiated from those due to reactive synovitis.

Lesions of the articular cartilage can also be identified in MR imaging due to changed signal intensity or decreased thickness of the articular cartilage.

Early recognition of carpal osteonecroses occurring as a result of carpal dislocations is possible only in MRI (Chapter 30).

Pattern of Injury

Perilunate and Lunate Dislocations

Perilunate dislocation is defined as a dislocation of the capitate and the lunate in the midcarpal joint. In most cases (97%), the capitate dislocates dorsally behind the lunate. In only 3% of cases, it dislocates in the opposite direction with a palmar dislocation of the head of the capitate (palmar perilunate dislocation or dorsal lunate dislocation). If the capitate dislocates away from the lunate, the scaphoid – which serves as a bridge between the proximal and the distal carpal rows – either also dislocates or fractures. If the scaphoid dislocates, the interosseous scapholunate ligament ruptures, the proximal scaphoid pole tears off from the radioscapholunate ligament, and the palmar radiocarpal ligaments are injured, including the radioscaphocapitate ligament.

The extent of the perilunate dislocation is divided into four degrees of severity ( Table 22.3 ):

The isolated dorsal translation of the proximal scaphoid pole in the radiocarpal joint without dislocation in the midcarpal joint leads to rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid (RSS), which is stage I of perilunate instability.

If, in addition to an RSS, there is also a midcarpal instability between the lunate and capitate-usually dorsal-this is stage II. Stages I and II are seldom found isolated.

When greater force is applied, the triquetrum also fractures or the lunotriquetral ligament ruptures. This constitutesstage III of perilunate instability ( Fig. 22.2 ).

Due to the tension of the long flexor and extensor muscles that cross over the carpus, there is an inherent tendency to reposition spontaneously. However, the dorsal lunate horn can prevent the displaced head of the capitate from sliding back into place. If the capitate forces its way back into a colinear aligned position to the radius, the lunate is displaced to the palmar side or, if the proximal extrinsic V ligaments are intact, it is rotated out on the palmar side, giving it a “tipped teacup” appearance. This is stage IV of perilunate instability ( Fig. 22.3 ). The lunate can be rotated up to 270° in the palmar-proximal direction in extreme cases. Additional malrotation to the ulnar side is also possible.

The dorsal perilunate dislocation and palmar lunate dislocation are actually different manifestations of the same injury. Both represent stage IV. The following subtypes deserve mentioning:

There is a partially reduced carpus as well as a lunate that is only partially dislocated toward the palmar aspect. The situation of a dorsal perilunate, palmar lunate dislocation is referred to as midcarpal dislocation ( Fig. 22.4 ).

Aside from the perilunate dislocation, individual carpal bones can also dislocate:

This usually involves the scaphoid, which can be displaced in the same direction (dorsal or palmar) as the rest of the carpus in relation to the radius ( Fig. 22.5 ).

Dislocation in the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint can be combined with dorsal rotation of the scaphoid of more than 90°.

Finally, the extremely rare isolated dislocation of the triquetrum from the proximal carpus is also possible. After it is disconnected from the lunotriquetral ligament, palmar rotational displacement occurs ( Fig. 22.6 ).

The displaced lunate is in danger of avascular necrosis (osteonecrosis of the lunate) if the dislocation is initially overlooked and is not reduced until weeks or months later.

The scapholunate ligament always tears when there is a perilunate dislocation. Only early and anatomically exact reduction gives the ligament the chance to heal. Surgical suture of the ligament is often no longer possible, and ligamentoplasty is sometimes limited in success with regard to long-time stability. A rotational instability of the scaphoid that remains after perilunate dislocation, leads to osteoarthritis over the years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree