Vascular |

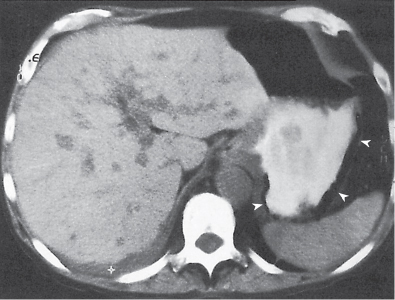

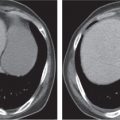

Ischemia/infarction

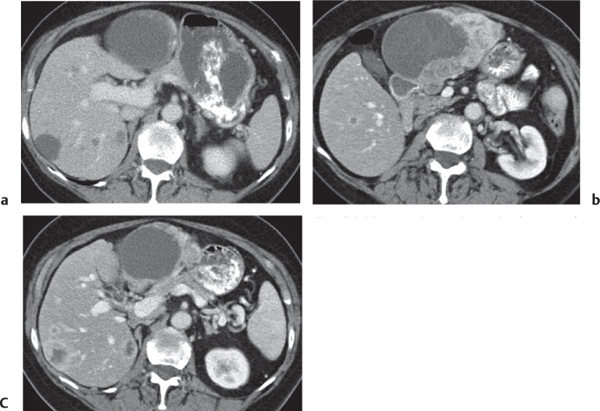

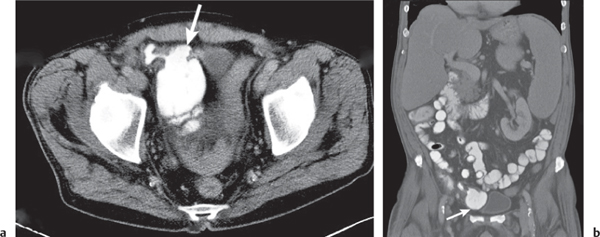

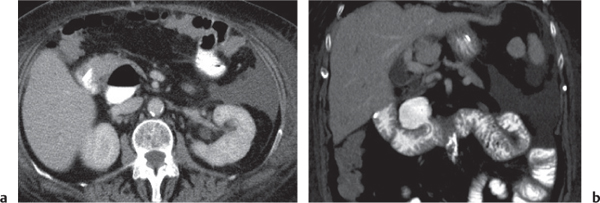

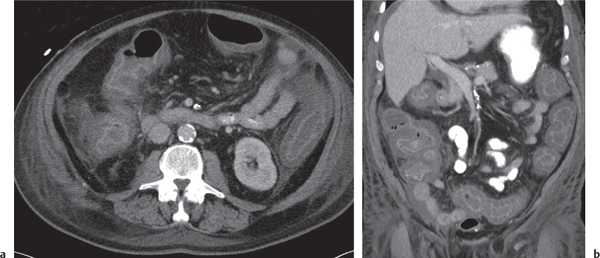

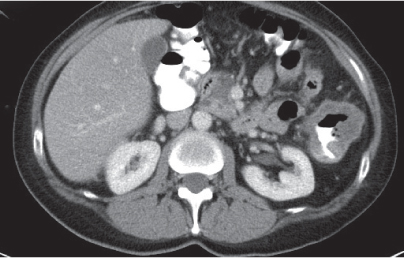

Fig. 24.28a–c |

Insufficient blood supply due to arterial or venous occlusion.

Diagnostic pearls: Markedly dilated small bowel loops and segmental wall thickening; clots in internal mammary artery and vein; three-layered appearance of bowel on postcontrast scans (target sign): low-attenuating edematous submucosa framed by hyperdense mucosa and serosa (i.e., shock bowel); stranding of mesenteric fat.

Pneumatosis intestinalis and mesenteric or portal venous gas are usually visible earlier on CT than on plain films. |

Typical symptoms are acute abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. Precipitating factors include bowel obstruction, vascular thrombosis, and recent surgery. Ischemic colitis is a predominantly left-sided, segmental, or diffuse disease and may mimic pseudomembranous colitis.

Arterial occlusion predominant cause (90%); venous occlusion accounts for < 10%. Prognosis depends on the speed of treatment and the amount of small bowel affected. |

Epiploic appendagitis

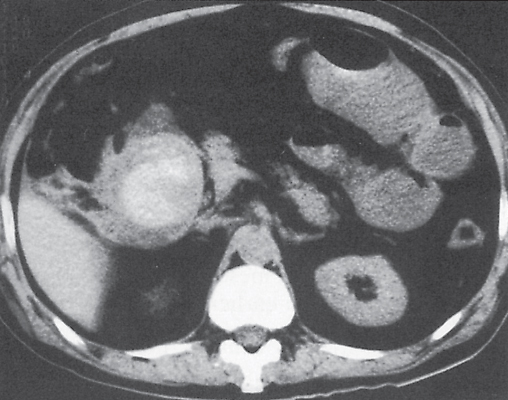

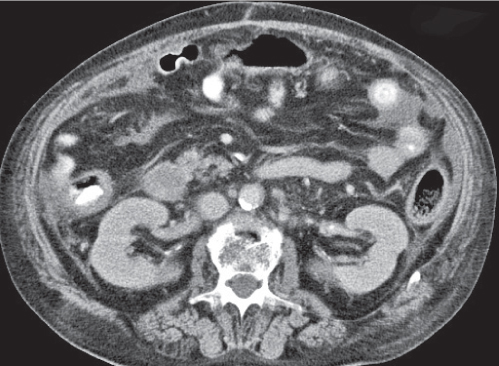

Fig. 24.29 |

Acute infarction/inflammation of epiploic appendages.

Diagnostic pearls: Oval to round pericolonic fatty mass with hyperattenuating ring, surrounded by stranding of mesenteric fatty tissue. |

Torsion of epiploic appendages leads to thrombosis and thus infarction of small veins.

Important differential diagnosis to diverticulitis and appendicitis. CT pattern is pathognomonic.

Treatment primarily with analgetics. Surgery only required in cases with larger infarctions. |

Infection |

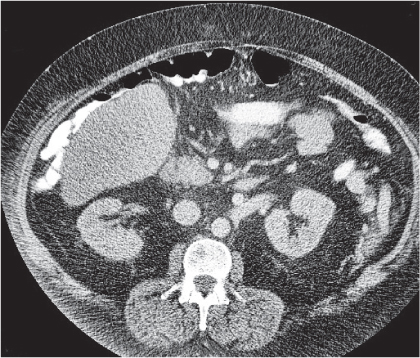

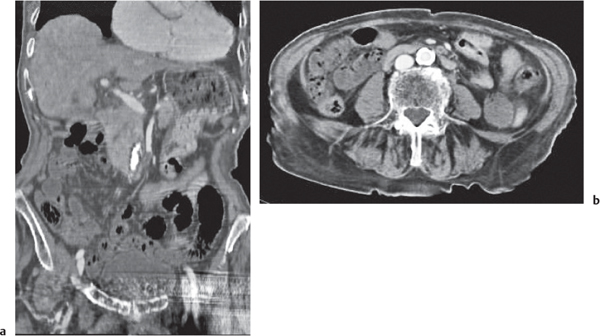

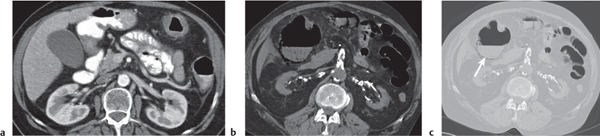

Typhlitis

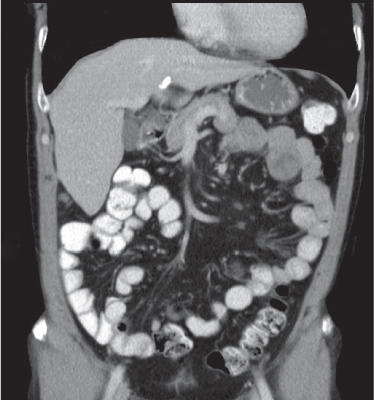

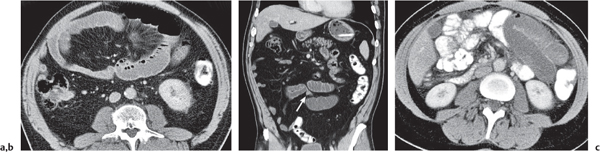

Fig. 24.30a, b |

Transmural inflammatory and sometimes necrotizing process.

Diagnostic pearls: Inhomogeneous wall thickening of the cecum and ascending colon; occasionally, spreading to the distal ileum and/or appendix. Pneumatosis and pericolic inflammatory changes are common. Perforation and pericolic abscess formation may occur. |

Histologically, an inflammatory process of the mucosa with deep ulcerations and necrosis due to local ischemia. Particularly observed in neutropenic patients, including leukanemia, HIV, chemotherapy, aplastic anemia, bone/organ transplants, and lymphoma.

Treatment of choice is antibiotics/antiinflammatory drugs. In severe cases, surgical resection is needed. |

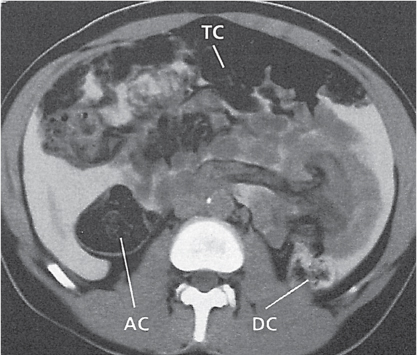

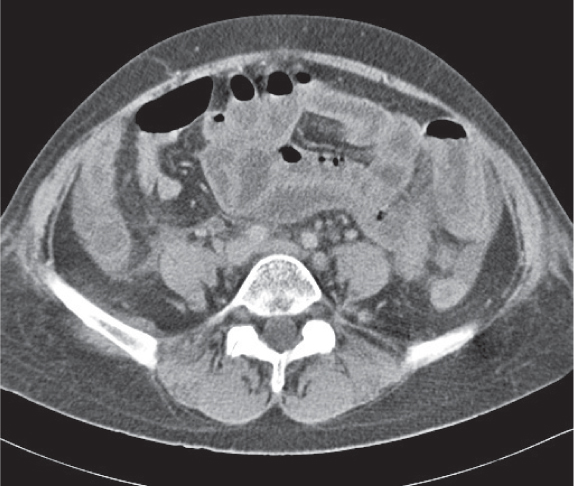

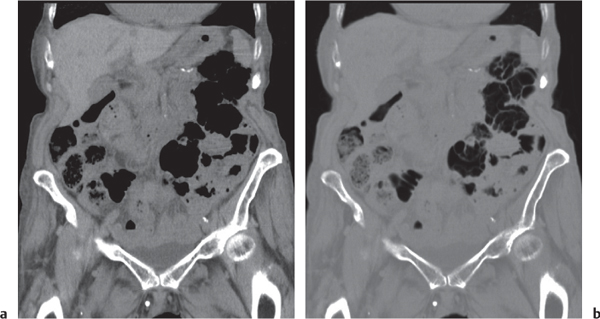

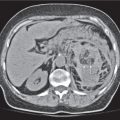

Pseudomembranous colitis

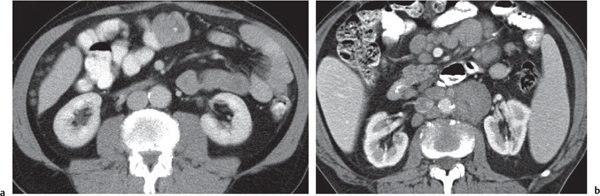

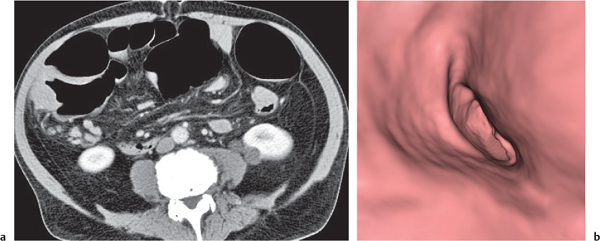

Fig. 24.31a, b |

Clostridium difficile–induced acute inflammation of the colonic mucosa with or without submucosa.

Diagnostic pearls: Pancolitis with nodular circumferential wall thickening (≤ 15 mm).

Oral contrast between the thickened folds may create an “accordion” sign. “Targetlike” appearance of colon wall: Hypodense (i.e., edematous) submucosa embedded between hyperintense mucosa and serosa.

Usually most prominent in the ascending and transverse colon. |

Usually a complication of antibiotic therapy with copious nonbloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and tenderness. Secondary to cytotoxin produced by C. difficile. CMV colitis causes wall thickening of the right colon and the terminal ileum only, without lymphadenopathy, and is usually seen in patients with AIDS. |

Infectious colitis |

Diffuse or segmental wall thickening with or without mucosal ulcerations.

Diagnostic pearls: |

|

|

Actinomycosis: Predominantly in the ileocecal and rectosigmoid colon. Cecum may appear shrunken (differential diagnosis: TB) but lack of mass or fistulous tracts. |

Actinomycosis: Typically in the wake of appendicitis or after insertion of intrauterine device (IUD). |

|

Amebiasis: Irregular thickening of the colonic wall sometimes masslike. Often skip lesions. Cecum is involved in 90% of cases. Ileum is spared. Campylobacter: Concomitant wall thickening of small intestine and colon. |

Amebic colitis: Often cannot be morphologically differentiated from primary adenocarcinoma or paracolic mass in the wake of diverticulitis. |

|

CMV: Nodular wall thickening involving cecum and proximal colon. May also affect the terminal ileum.

E. coli: May primarily affect the transverse colon but often the whole colon. |

CMV: Without biopsy, difficult to differentiate from Crohn disease diagnosis. |

|

Herpesvirus/chlamydia/gonorrhea: Typically found in the rectosigmoid colon.

Histoplasmosis: Usually affects ileocecal region.

Salmonellosis/yersiniosis: Predominantly ileum, but may also spread to cecum and right colon.

Schistosomiasis: Multiple polypoid filling defects in the sigmoid colon or rectum. Larger lesions may mimic carcinoma.

Shigellosis: Nodular mucosal thickening affecting mainly the left-sided colon. |

Herpesvirus/chlamydia/gonorrhea: Usually sexually transmitted.

Histoplasmosis: May mimic appendicitis.

Salmonellosis/yersiniosis: Both always involve the ileum. Marked thickening of wall and folds.

Schistosomiasis: Filling defects (granulomas) are a late manifestation of heavy infestation and chronic exposure to Schistosoma. |

|

TB: Thick-walled, shrunken cecum, narrowed terminal ileum, and thickened ileocecal valve (Fleischner sign). Worm infestation (Ascaris and Trichuris): Bolus of ascariasis may cause a solitary filling defect. Trichuriasis may induce excessive mucus production and numerous irregular filling defects. |

TB: Colonic TB is almost exclusively limited to the cecum. May lead to neoplasmlike colonic stenoses. Worm infestation: Trichuris trichiura is a relatively common inhabitant in the cecum and appendix. Symptomatic infections occur commonly in the tropics and subtropics. |

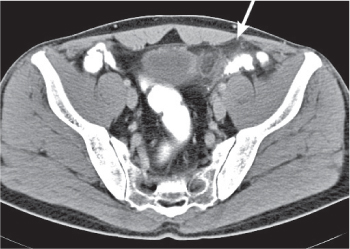

Appendicitis

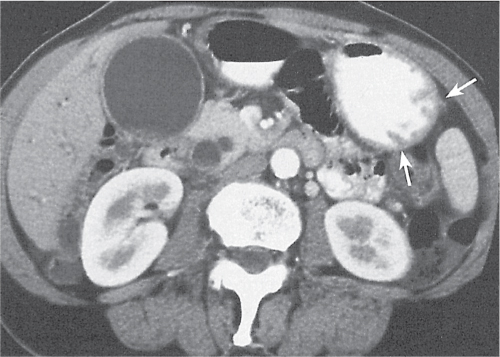

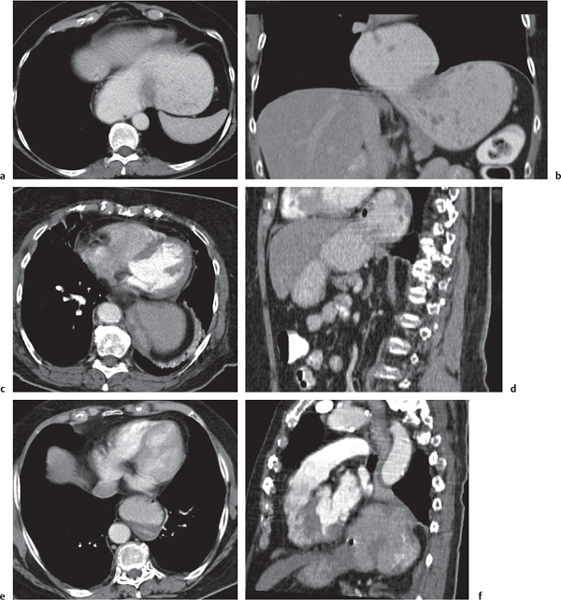

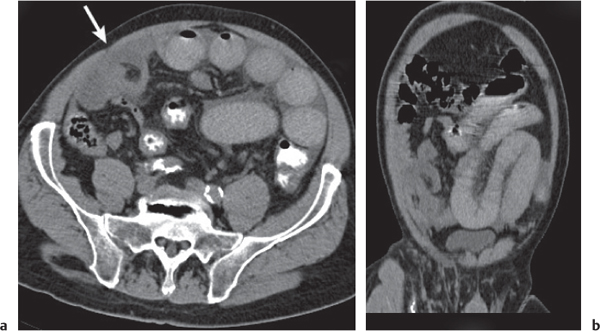

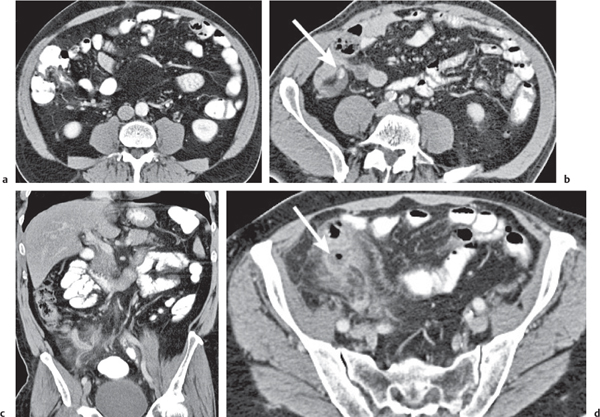

Fig. 24.32a–d |

Inflammation and subsequent infection of the appendix due to an acute luminal obstruction.

Diagnostic pearls: Dilated appendix (> 6 mm), hyperattenuation and thickening of appendicular (and sometimes also cecal) wall, and periappendicular fat stranding. Calcification represents a fecalith. |

An appendicular abscess appears as a well-demarcated fluid collection in the right lower quadrant of the pelvis.

High diagnostic accuracy (> 97%) for CT as compared with all other diagnostic methods.

Differential diagnoses: diverticulitis and epiploic appendagitis. |

Diverticulosis |

Small, flask-shaped, air-containing diverticula in the colonic wall. Usually incidental finding. |

Occurs in 6% to 8% of the Western population, increasing with age. Highest incidence in the sigmoid. |

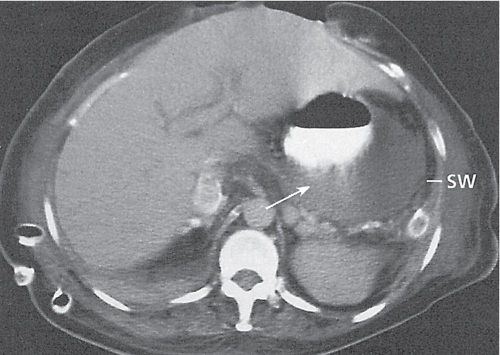

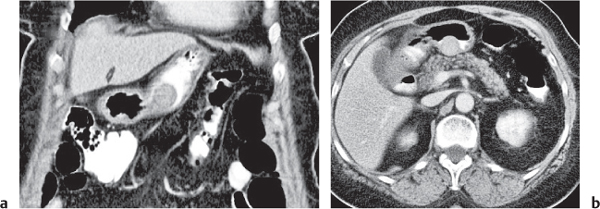

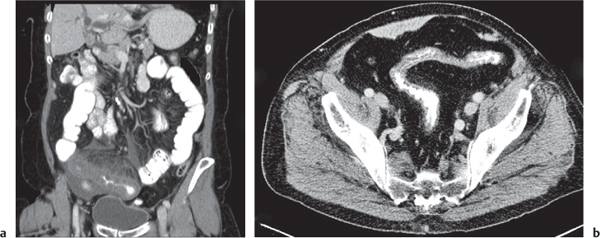

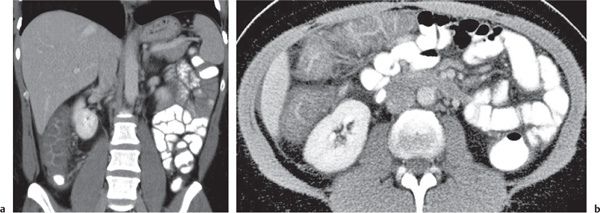

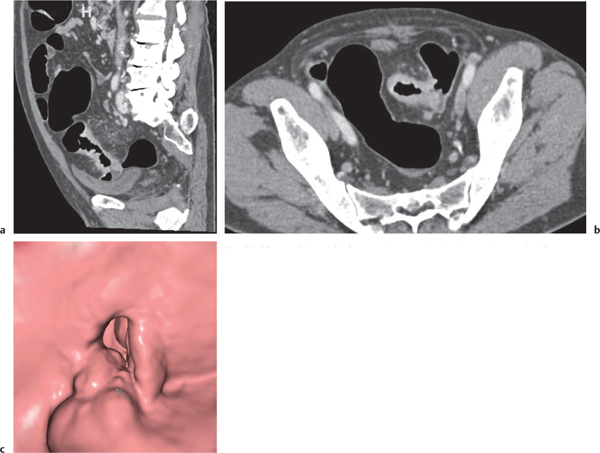

Diverticulitis

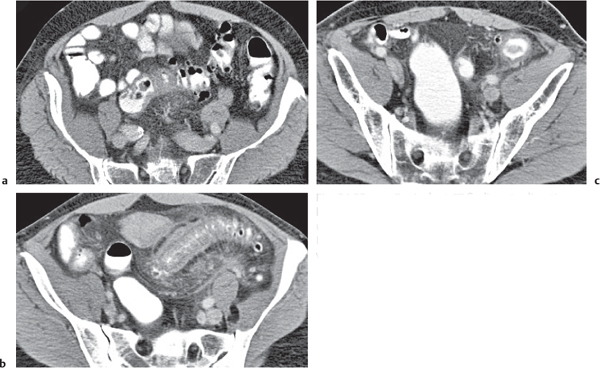

Fig. 24.33a–c |

Inflammation with or without perforation of saccular outpouchings in the antimesenteric colon wall.

Diagnostic pearls: Diverticula, segmental mural thickening, and luminal narrowing in combination with mesenteric fat stranding are highly suspicious for diverticulitis (stage I/IIA).

Locoregional mesenteric gas points to abscess formation (stage IIB).

Free intra-abdominal gas is indicative of free perforation (stage IIC).

Use lung and abdominal window/level settings for assessment. |

Occurs in 10% to 25% of patients with diverticulosis due to obstruction of the diverticular neck and subsequent diverticular distention and perforation.

Staging and management per Hansen and Stock:

Stage 0: Asymptomatic diverticulosis

Stage I: Inflammation restricted to bowel wall (i.e., no wall thickening)

Stage IIA: Phlegmonous

Stage IIB: Abscess-forming

Stage IIC: Free perforated

Stage III: Chronically relapsing

Stages I and IIA are usually managed conservatively, stages IIB and III, surgically. |

Trauma |

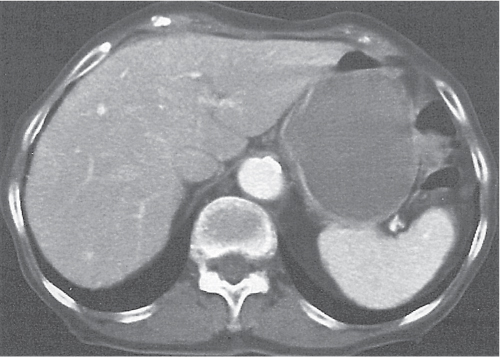

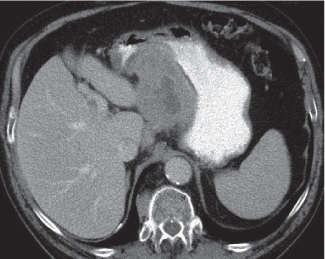

Hematoma/laceration

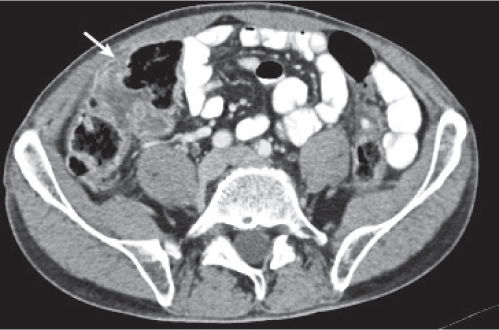

Fig. 24.34 |

Focal thickening of the bowel wall.

Diagnostic pearls: Hyperattenuating (52–80 HU) solid intramural mass on noncontrast scans.

A partially cystic mass with fluid layers may be observed in cases of anticoagulation-induced bleeding. |

Intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage may be associated. |

Perforation |

Pneumoperitoneum or pneumoretroperitoneum.

Diagnostic pearls: Extraluminal oral contrast specific for colon perforation.

Extraluminal/intra-abdominal gas not specific for colon perforation (alternative causes may be barotraumas and mechanical ventilation). |

Use lung and abdominal window/level settings for image assessment. |

Inflammation |

Crohn colitis

Fig. 24.17 , p. 749 |

Discontinuous chronic recurrent transmural inflammation.

Diagnostic pearls: Thickening of the bowel wall and “sandwich” sign of bowel wall (edematous submucosa between hyperattenuating mucosa and serosa). Abscesses, fistulas, and regional adenopathy may be present. |

Terminal ileum involved in 80%, ascending colon in 20% to 55%. Rectum and sigmoid are usually spared. Initial inflammation is confined to the mucosa; thus, barium study and endoscopy are more sensitive for detecting these changes. |

Ulcerative colitis |

Idiopathic chronic inflammation affecting primarily the colorectal mucosa and submucosa.

Diagnostic pearls: Pancolitis with thickened target-like colonic wall (< 10 mm), luminal narrowing, stranding of pericolonic fat, and fibrofatty perirectal proliferation (presacral space > 2 cm).

Changes may be only subtle and constricted to the rectum.

Extraluminal extension of the disease is uncommon, unlike in Crohn disease. |

Chronic inflammation confined to the mucosa and exclusively progressing retrograde and continuous from the rectum to the cecum. Within the first 10 y, the risk of colonic cancer increases by 2% annually. Barium enema and colonoscopy are much more sensitive than CT in the diagnosis of initial inflammation. |

Radiation enteritis |

Iatrogenic-induced damage to the bowel wall due to therapeutic abdominal irradiation.

Diagnostic pearls:

Acute changes: Nonspecific wall thickening, target sign

Chronic changes: Bowel wall thickening, fibrosis, and luminal narrowing

Perirectal fat proliferation (> 10 mm) with accompanying pararectal fibrosis (halo sign). |

Complication after radiation therapy with > 40 to 50 Gy.

Affects ~10% of treated patients.

Radiation enteritis may occur up to 20 y after treatment, radiation colitis within 2 y after radiation. Typically confined to the rectum (pelvic irradiation is very common). |

Graft versus host reaction

Fig. 24.16 , p. 749 |

Rare concomitant bowel affection in patients who underwent bone marrow transplantation. Diagnostic pearls: Diffuse nonspecific mural thickening involving the entire intestine from the stomach to the colon, as well as stranding of mesenteric fat and lymphadenopathy. |

The most common GI complication after bone marrow transplantation. Clinical symptoms are profuse secretory diarrhea, cramping, and malabsorption caused by immunocompetent T cells of the donor reacting against host tissues. |

Colitis cystica profunda |

Rectosigmoid wall thickening due to multiple submucosal cysts.

Diagnostic pearls: Multiple, up to 2-cm submucosal low-density cystic lesions in the rectum with or without sigmoid. |

Unknown etiology (inflammatory or traumatic).

The cysts are filled with thick mucinous material and lined by a cuboidal flattened epithelium.

Presents clinically with bright rectal bleeding, mucus discharge, and diarrhea.

Commonly associated with solitary ulcer syndrome and rectal prolapse. |

Amyloidosis |

Submucosal deposition of fibrils of light-chain immunoglobulins.

Diagnostic pearls: Normal or thickened rectal wall with small hypoattenuating polypoid lesions.

On venous phase images, delayed contrast enhancement may be present. |

May be primary or secondary.

Preferentially involves the rectal submucosa, which thus represents a preferred site for diagnostic biopsy (even in the absence of CT findings). |

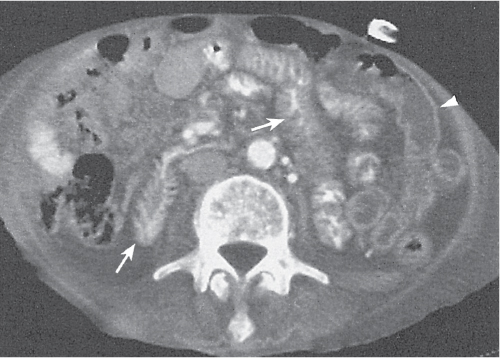

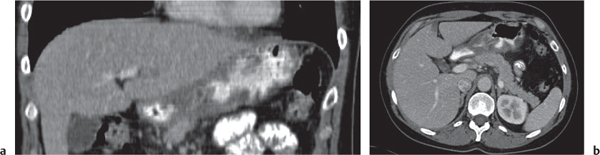

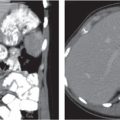

Pneumatosis cystoides coli

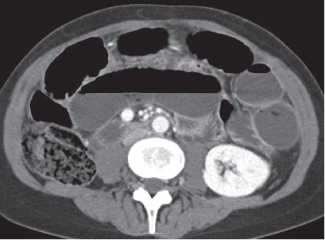

Fig. 24.35a, b |

Cystic/linear gas collection in submucosal/subserosal layers of the GI tract.

Diagnostic pearls: Intramural gas collection within normal-sized colonic wall.

Findings may be completely missed on soft tissue CT images (lung window is the key). |

May be idiopathic, associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or secondary to surgery or ischemia.

Lack of intravascular or biliary air (liver) indicates idiopathic origin. |

Benign neoplasms |

Lipoma |

Diagnostic pearls: Submucosal mass with fatlike density and smooth margins. |

The most common submucosal tumor in the colon. Typically occurs in the cecum and ascending colon. |

Leiomyoma |

Diagnostic pearls: Large, strongly enhancing soft tissue mass in the bowel wall that may contain necrosis and ulceration. |

Rare in the colon, more common in the upper GI tract. |

Schwannoma |

Diagnostic pearls: Multiple strongly attenuating tumors characteristically located on the mesenteric side of the colon. May show central necrosis. |

Associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (Recklinghausen disease). |

Malignant neoplasms |

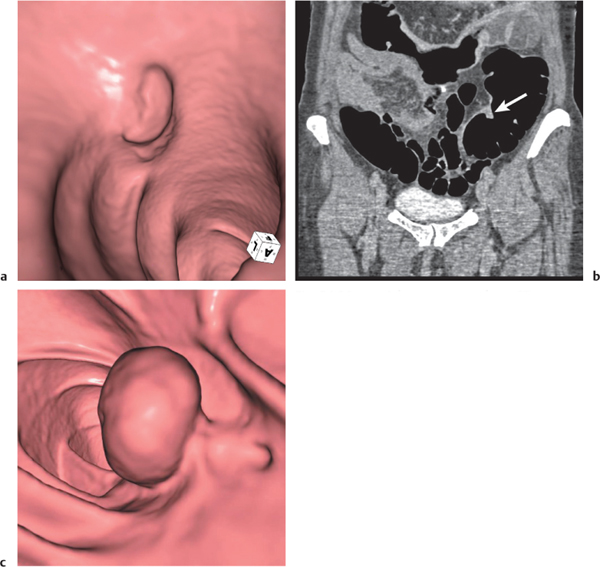

Adenomatous polyp

Fig. 24.36a,b |

Sessile or broad-based polypoid mass in the luminal side of the colonic wall.

Diagnostic pearls: Incidental finding on axial CT scans. Polyps usually enhance after contrast.

Apply CT virtual colonoscopy.

Use prone and supine scans (to differentiate from stool). |

Adenomatous polyps account for > 50% of all polyps; > 2 cm considered malignant.

Multiple polyps may be associated with a polyposis syndrome.

CT colonoscopy allows detection of polyps ≥ 10 mm with > 95% accuracy.

CT colonoscopy requires adequate patient preparation (bowel cleansing, stool tagging, and CO2 insufflation). |

Villous adenoma |

Adenomatous polyp containing predominantly villous elements.

Diagnostic pearls: Low-attenuating (< 10 HU), irregular polypoid mass, usually located in the rectum or sigmoid colon. May occupy > 50% of the lumen. |

Characteristic CT appearance of villous adenomas is based on high mucus content. When using CT to evaluate a suspected villous adenoma, oral and rectal contrast material should not be used. |

Giant anorectal condyloma acuminatum |

Sexually transmitted wart in the rectoanal region.

Diagnostic pearls: Attenuating infiltrating mass with a cauliflower-like surface appearance and subcutaneous tissue/perirectal fat infiltration. |

Associated with human papillomavirus. Also called Buschke–Löwenstein tumor. May show different histologic patterns and even malignant transformation. CT cannot distinguish histologic subtypes. |

Carcinoid |

Neuroendocrine tumors arising from endocrine cells.

Diagnostic pearls: Polypoid soft tissue mass is found in the appendix or right colon, less commonly in the rectum.

Strong enhancement is seen during the arterial phase. |

Small appendicular carcinoids are usually benign. Large, broad-based intraluminal tumors in elderly patients suggest a less common malignant carcinoid. Flush symptom occurs after hepatic spread. |

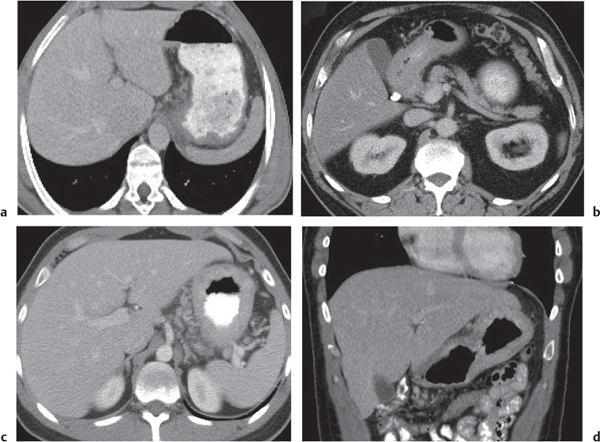

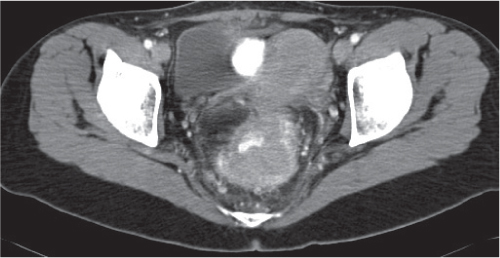

Adenocarcinoma

Fig. 24.37a–c

Fig. 24.38 , p. 764 |

Segmental wall thickening and luminal narrowing.

Diagnostic pearls: Intraluminal or intramural mass, often no or only distinct attenuation; extracolonic growth, necrosis, and perforation. Stranding of pericolonic fat indicates transmural growth. Low-attenuation and subtle calcifications are typical for mucinous adenocarcinoma. |

Adenocarcinomas represent 95% of all colon cancers. Histologic subtypes are mucinous (signet ring cells), mucin-producing, and colloid.

Most common tumor of the GI tract.

Lymphatic spread and size of lymph nodes do not correlate.

Modified Dukes staging:

Stage A (T1N0M0): Restricted to (sub) mucosa

Stage B (T2or3N0M0): Limited to serosa/pericolonic tissue

Stage C (T2or3N1M0): Lymphatic spread

Stage D (any T, any N, M1): Distant metastases |

Metastatic disease

Fig. 24.38 , p. 764 |

Segmental or multifocal wall thickening with or without luminal narrowing.

Diagnostic pearls: Features usually are indistinguishable from those of primary colonic cancer. |

Primary tumors of the uterus, ovary, prostate, bladder, pancreas, kidney, and stomach may directly invade nearby colonic segments or induce distant seeding through ascites. |

Lymphoma

Fig. 24.39 , p. 764

Fig. 24.40a, b , p. 764 |

Segmental wall thickening with mucosal ulcerations.

Diagnostic pearls: Most common in the cecum. Associated with massive mesenteric/retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. |

Rare; represents only 1.5% of all abdominal lymphoma. Usually non–Hodgkin lymphoma. |

Other |

Mechanical bowel obstruction |

Primary or secondary obstruction of the small intestine.

Diagnostic pearls:

Simple obstruction: Dilated fluid-filled, thin-walled loops of small intestine with or without air–fluid levels.

Closed loop obstruction: Obstruction at two ends. One or several grossly distended fluid-filled U-shaped loops with two adjacent limbs showing a zone of abrupt transition (i.e., incarceration).

Strangulating obstruction: Slight circumferential wall thickening and enhancement (target sign), as well as engorgement of mesenteric vessels, indicate mild ischemia. |

Causes may be intrinsic or extrinsic. Typical extrinsic causes are diverticulitis, appendicitis, hernias, adhesions, and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Typical intrinsic causes are intraluminal lesions, neoplasms, inflammations, and infections. |

Colonic pseudo-obstruction |

Dilated colonic loops containing gas, stool, and possibly contrast medium.

Diagnostic pearls: Often concomitant dilation of small bowel loops.

CT findings in general are nonspecific. |

Pseudo-obstruction may be induced by ischemia, inflammation (toxic megacolon), impaired neuromuscular function (diabetic neuropathy, uremia, and hypokalemia), postoperative paralytic ileus, and iatrogenic causes (vagotomy and irradiation). |