25 Peritoneum and Mesentery

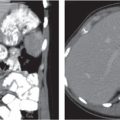

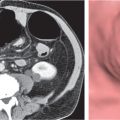

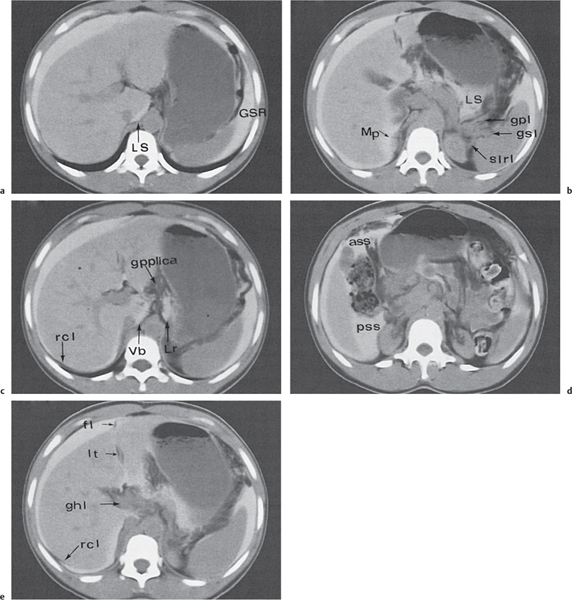

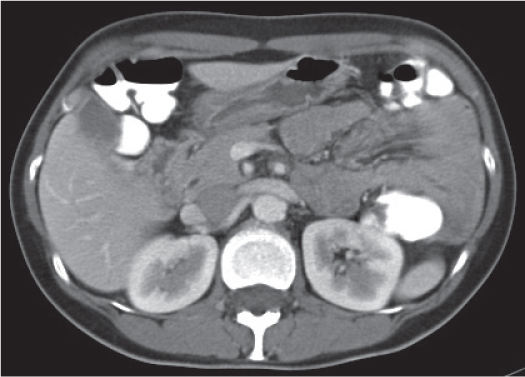

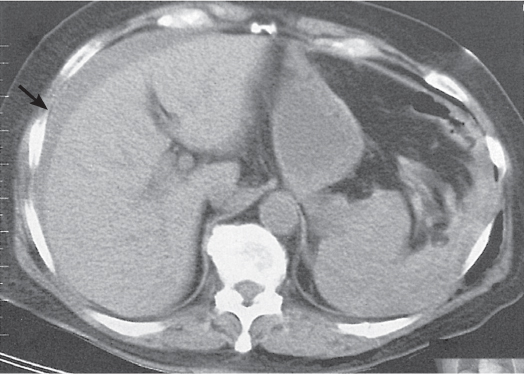

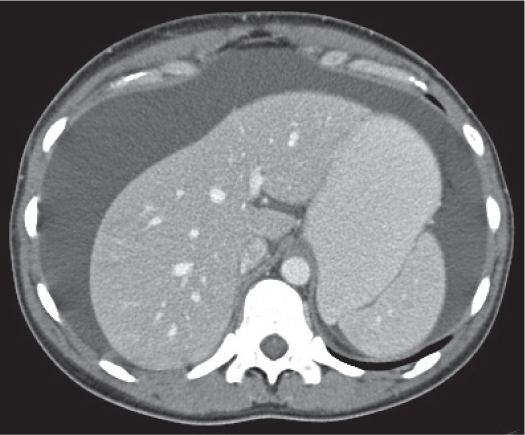

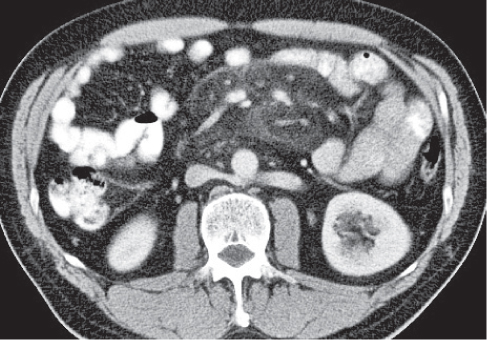

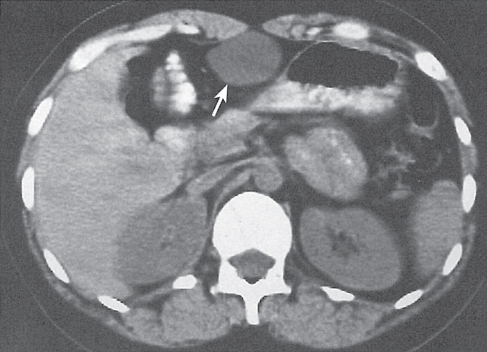

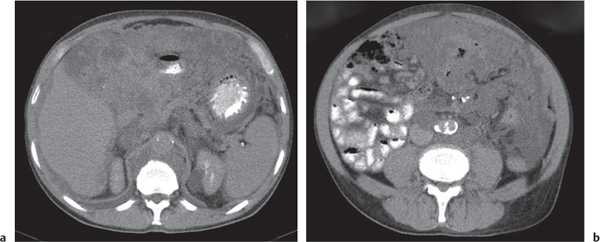

The peritoneal space is an anatomically complex cavity and under normal physiological conditions nonvisible on computed tomography (CT) scans. However, Fig 25.1 displays CT scans of a patient with heavy ascites, which has been made even more attenuating through intraperitoneal contrast application. In combination with Fig. 25.2 , it thus allows for an identification of all relevant peritoneal structures and spaces.

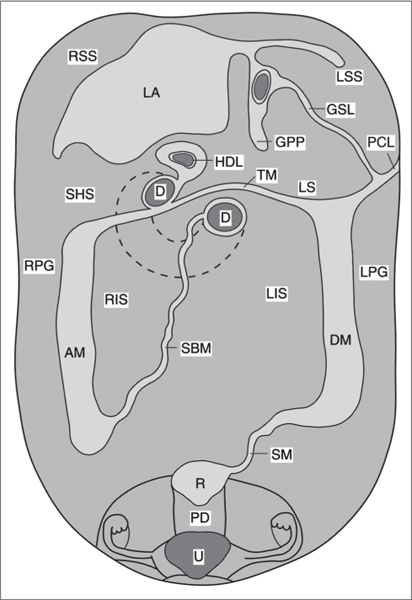

The peritoneal cavity is subdivided by peritoneal plicas into several different compartments and recesses (Fig. 25.2), which are anatomically interconnected.

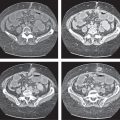

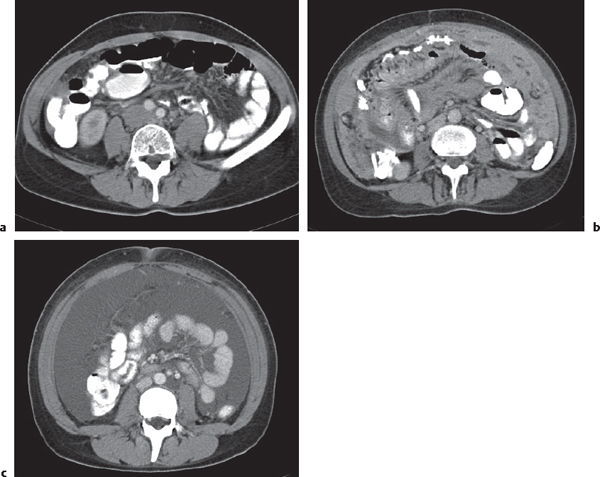

The transverse mesocolon, which affixes the transverse colon to the retroperitoneum, is a major barrier dividing the abdominal cavity into supramesocolic and inframesocolic compartments. The inframesocolic compartment or space is further subdivided by the small bowel mesentery into the right and left inframesocolic space.

The right inframesocolic space is laterally defined by the peritoneal attachment of the ascending colon, as well as medially and caudally by the mesenteric root.

The left inframesocolic space is laterally and caudally to the left delineated by the peritoneal attachments of the descending colon and the sigmoid. On the right side, it opens caudally into the right paracolic gutter, which lies lateral to the mesenteric attachment of the ascending colon. The left paracolic gutter lies lateral to the peritoneal attachments of the descending colon and the sigmoid. These four inframesocolic spaces and barriers are better visualized on cross-sectional CT scans than the transverse mesocolon.

The supramesocolic space is subdivided into the right and left subphrenic spaces, the subhepatic space, the Morison pouch, and the lesser sac. On the right side, the right paracolic gutter extends cranially into the posterior subhepatic space and the Morison pouch, which represents the most dependent portion of the peritoneal cavity in the right upper quadrant. It also is a frequent site of intraperitoneal fluid collections, which may extend even to the right subphrenic space (supramesocolic space) if the fluid volume suffices. Both paracolic gutters connect the inframesocolic space with the pelvis, where the pouch of Douglas and two lateral paravesical recesses are the most dependent parts and thus frequent sites of intraperitoneal fluid collections.

Because the left coronary ligament lies more anteriorly as compared with the right, the left subphrenic space extends less posteriorly than the right. The lesser sac lies dorsally to the lesser omentum, the stomach, the duodenum, and the gastrocolic ligament but ventrally to the body of the pancreas and the spleen. It is connected with the peritoneal space through the foramen of Winslow, or foramen epiploicum—which hides behind and below the porta hepatis. The lesser sac may extend downward between the anterior and posterior plicas of the greater omentum. The superior recess of the lesser sac usually extends upward to the diaphragm surrounding the caudate lobe of the liver (Fig. 25.1a).

The mesentery of both the small and large bowel and various ligaments provide a barrier not only for the free movement of fluid, cells, and germs but also for the direct spread of diseases within the abdominal cavity. However, in the absence of ascites, identification of individual ligaments may be difficult, as mesentery and intraperitoneal fatty tissue show similar Hounsfield unit (HU) values. Mesentery and ligaments contain blood vessels and therefore may be better identified on postcontrast CT-scans. Mesenteric lymph nodes usually are not discernible due to their predominant fat content. Only reactive nodes appear as well-defined oval or round soft tissue densities.

Nevertheless, several ligaments of the supramesocolic cavity usually can be identified on CT scans.

The right triangular ligament forms from the coalescence of the superior and inferior plica of the right coronary ligament and separates the right subphrenic space from the Morison pouch. The left triangular ligament forms from the superior and inferior plica of the left coronary ligament and is located along the superior aspect of the left hepatic lobe.

The gastrophrenic ligament runs from the dome of the left diaphragm to the stomach and is easily missed on CT.

The gastropancreatic plica (Fig. 25.1b) forms around the proximal left gastric artery as it courses superiorly. It attaches the gastric fundus to the retroperitoneum and partially separates the superior recess of the lesser sac from the splenic recess.

The falciform ligament (Fig. 25.1c) is a remnant of the ventral mesogastrium, which contains the ligamentum teres and the obliterated umbilical vein. This vein may be recanalized in situations with decreased venous hepatic outflow.

The gastrosplenic ligament (Fig. 25.1d) is a remnant of the dorsal mesogastrium, connecting the greater curvature of the stomach with the splenic hilum. It contains short gastric arteries (rami gastrici breves), forms the lateral border of the lesser sac, and may be affected by processes of the stomach or pancreatic tail.

The phrenicocolic ligament is fixed to the spleen and attaches the proximal part of the descending colon to the left hemidiaphragm. By separating the left subphrenic space from the remainder of the peritoneal cavity, it inhibits free flow from the left paracolic gutter to the left subphrenic space. Pancreatic processes can spread via this ligament and involve the splenic flexure of the colon.

The gastrocolic ligament connects the greater curvature of the stomach with the superior aspect of the transverse colon. It contains gastroepiploic vessels and forms a portion of the greater omentum.

The gastrohepatic ligament is part of the lesser omentum and connects the medial aspect of the liver with the lesser curvature of the stomach. It contains the left gastric artery, coronary vein, and small lymph nodes. It is a common site of varices, pancreatic phlegmon, and metastases from malignant esophageal, gastric, or biliary neoplasms.

The hepatoduodenal ligament represents the inferior edge of the gastrohepatic ligament and delineates the foramen of Winslow.

ass | falciform ligament |

ghl | anterior subhepatic space |

fl | gastrohepatic ligament |

gpl | gastropancreatic ligament |

gpplica | gastropancreatic plica |

gsl | gastrosplenic ligament |

GSR | gastrosplenic recess |

Lr | lesser sac |

lt | lateral recess of the lesser sac |

LS | Morison pouch |

pss | ligamentum teres |

Mp | right coronary ligament |

slrl | posterior subhepatic space |

rcl | splenorenal ligament |

Vb | vestibulum |

D | duodenum |

GPP | gastropancreatic plica |

GSL | gastrosplenic ligament |

HDL | hepatoduodenal ligament with portal vein |

LA | liver attachment |

LS | lesser sac |

LSS | left supramesocolic space |

PCL | phrenicocolic ligament |

RSS | right supramesocolic space |

SHS | subhepatic space |

TM | transverse mesocolon |

Inframesocolic compartment. | |

AM | attachment of ascending mesocolon |

DM | attachment of descending mesocolon |

LIS | left infracolic space |

LPG | left paracolic gutter |

PD | pouch of Douglas |

R | rectum |

RIS | right infracolic space |

RPG | right paracolic gutter |

SM | root of the mesentery |

U | uterus and adnexa |

It extends from the proximal duodenum to the porta hepatis and contains the common hepatic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery, and portal vein. It is a common route for spreading of carcinomas of the gallbladder and the biliary system.

The transverse mesocolon lies in the inframesocolic abdomen, contains middle colic vessels, and is a common site for spreading of pancreatic or colic processes.

The greater omentum is located anterior to the small bowel and represents the inferior continuation of the gastrocolic ligament. It is formed by a double reflection of the dorsal mesogastrium and has four layers of peritoneum.

The small bowel mesentery extends from the ligamentum of Treitz in the left upper quadrant down to the ileocecal valve, totaling a distance of ~15 cm. It contains superior mesenteric vessels.

The sigmoid mesocolon contains sigmoid and hemorrhoidal vessels and forms a pathway from the pelvis to the abdomen as it coalesces with the broad ligament in women. Infections and neoplasms of the sigmoid can spread not only to the pelvis, but also vice versa, with ovarian processes involving the sigmoid colon.

The broad and round ligaments serve as anterior suspenders of the uterus. The broad ligament contains uterine vessels branching from the internal iliac vessels, as well as lymph vessels and nerves. The ureters course distally through the base of the broad ligament. The lowermost portion of the broad ligament is called the cardinal ligament, which is the main supporter of the cervix and upper vagina. The round ligaments extend into the inguinal canal and farther down to the labia majora.

The medial umbilical ligament and the lateral umbilical folds are two ligament-like structures within the anterior wall of the abdomen. The latter contain hypogastric vessels.

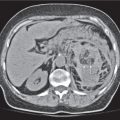

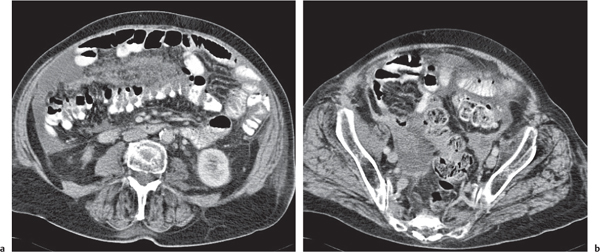

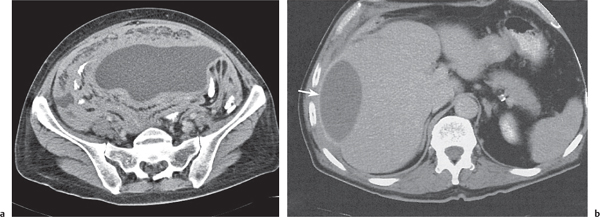

Free intraperitoneal fluid can be seen on CT scans only in the presence of volumes > 50 mL. In the supramesocolic compartment, it initially collects within the Morison pouch and extends from there via the paravesical fossae into the paracolic gutters. In the inframesocolic compartment, fluid preferentially collects in the fossa of Douglas. In the presence of large amounts of as-cites, bowel loops typically are centrally positioned, and the mesentery can be clearly delineated.

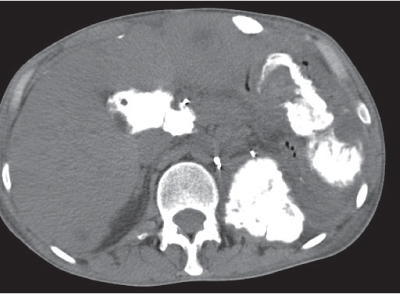

Loculated (encapsulated) ascites indicates adhesions, whether benign or malignant. Thus, bowel loops do not float free within the central abdomen, but are displaced by loculated fluid. Unfortunately, CT attenuation of benign and malignant ascites is similar, thus rendering any CT-based differentiation impossible. Instead, distribution patterns may be suggestive. Unlike benign ascites, the amount of malignant ascites in the lesser sac typically matches the amount observed within the peritoneal cavity. Fluid predominantly confined to the lesser sac is more typically characteristic of diseases of the pancreas or abscesses of the lesser sac. Abscesses are loculated fluid collections with mass effect. CT attenuation usually is between 15 and 35 HU. The most sensitive CT feature is the presence of extraluminal gas, which is seen in only ~30% of all abscesses. (Loculated gas within any abdominal mass is always indicative of an abscess or necrosis formation.) A well-defined, hyperattenuating wall is a classic feature of a mature abscess.

CT is superior to plain film radiographs in detecting free intraperitoneal air, which usually collects ventrally in the midabdomen, beneath the abdominal musculature. Following surgical interventions, small amounts of free air may be detected up to 7 days on CT scans.

Relevant peritoneal and mesenteric processes can usually be identified on nonenhanced CT scans. Postcontrast scans are often useful to better delineate vessels and differentiate between solid and necrotic and cystic lesions. Irrespective of the scan technique, mesenteric abnormalities are detected much easier if the intestines are well opacified and thus in patients who previously received sufficient oral contrast. Usually patients should drink 1.5 L over a period of 60 to 90 minutes prior to the scan. On the CT table, rectal infusion of contrast media may further increase diagnostic accuracy. Table 25.1 lists the most relevant differential diagnoses of the peritoneum and mesentery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree