Renal ectopy

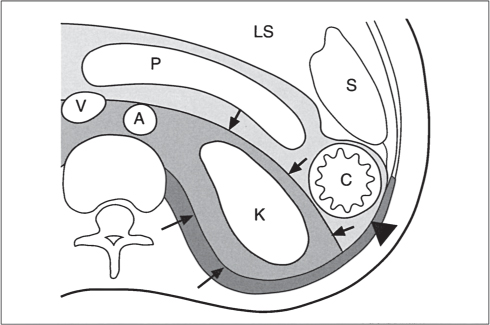

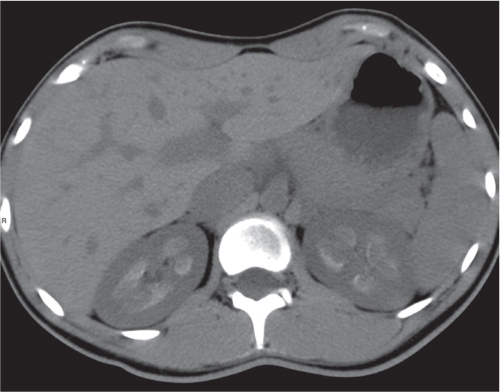

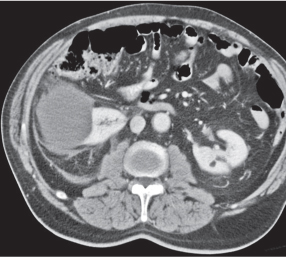

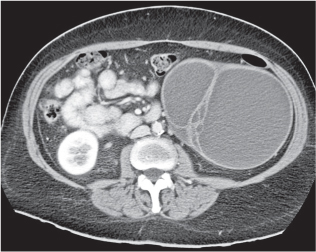

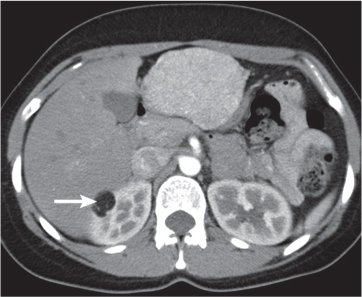

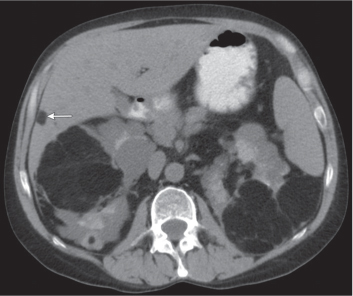

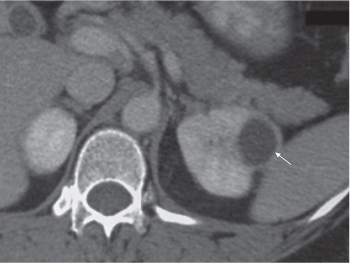

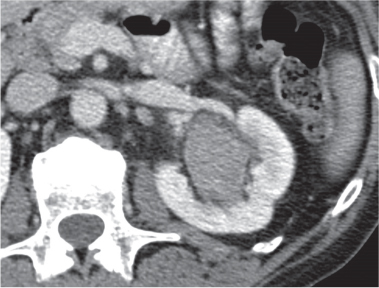

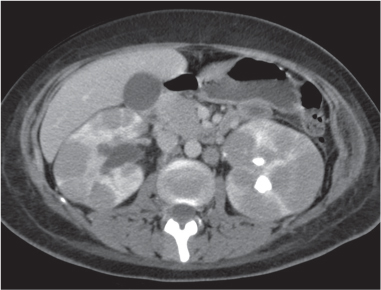

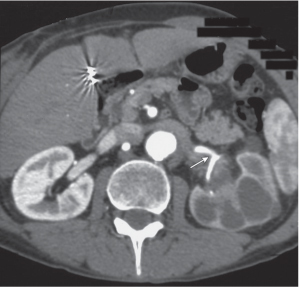

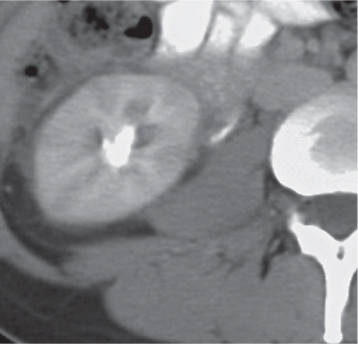

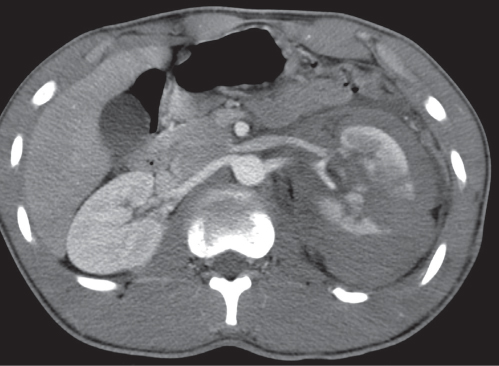

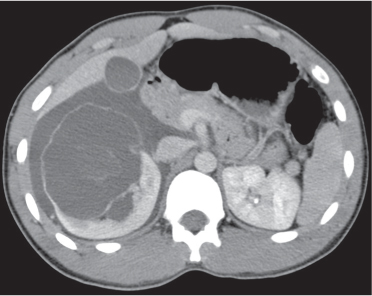

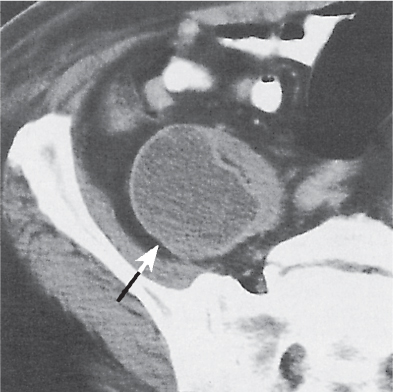

Fig. 27.11

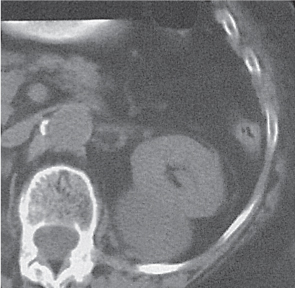

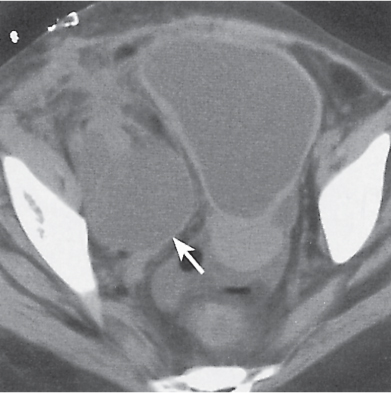

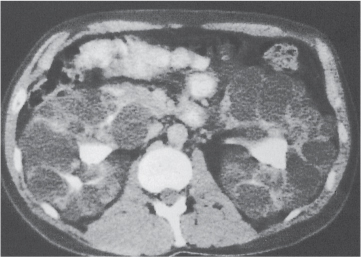

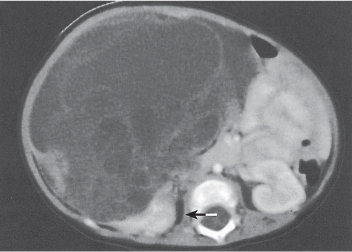

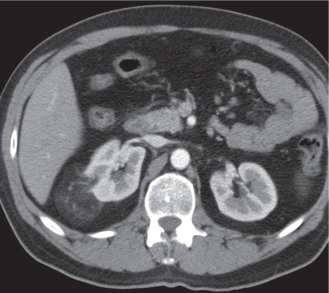

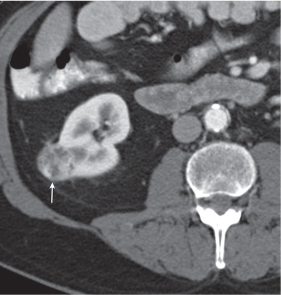

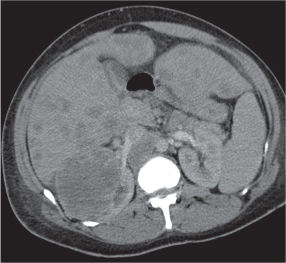

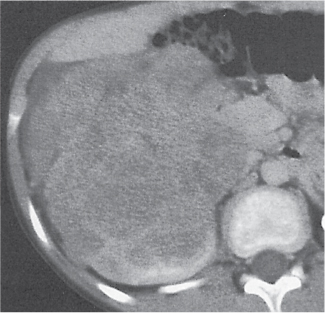

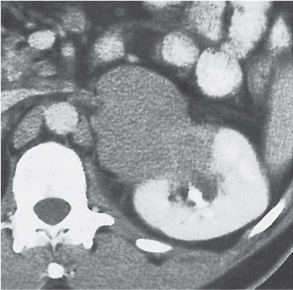

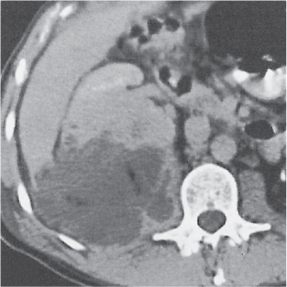

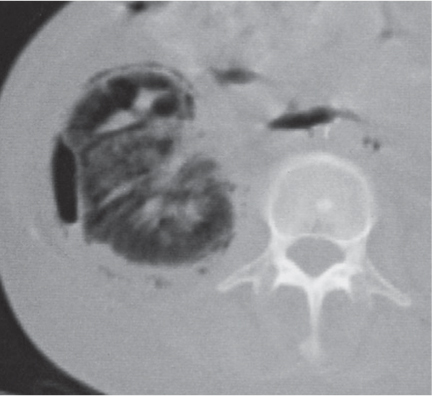

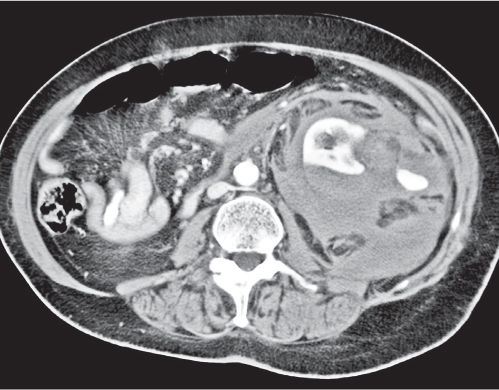

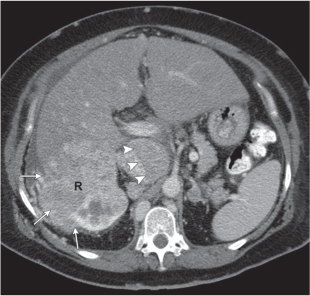

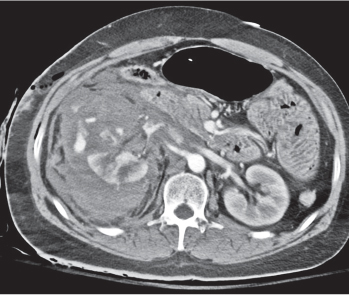

Fig. 27.12

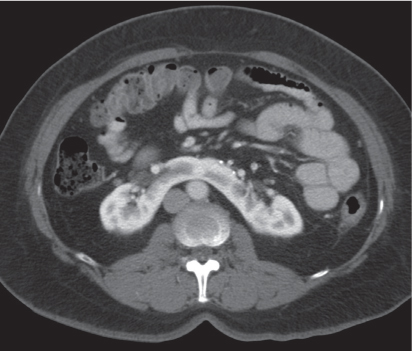

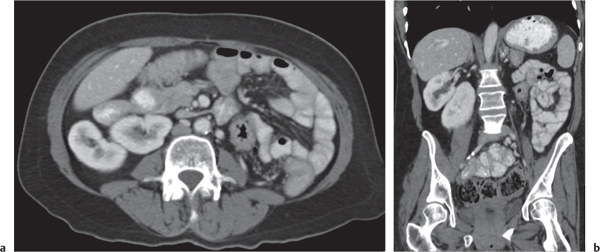

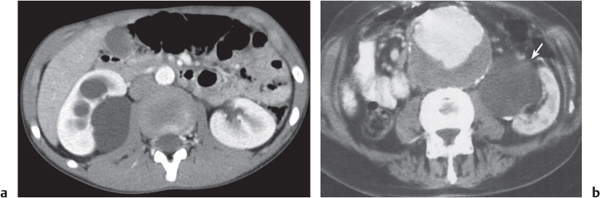

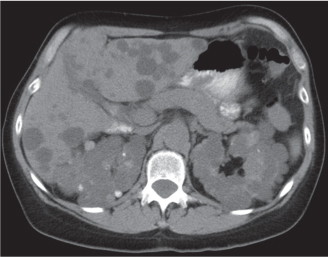

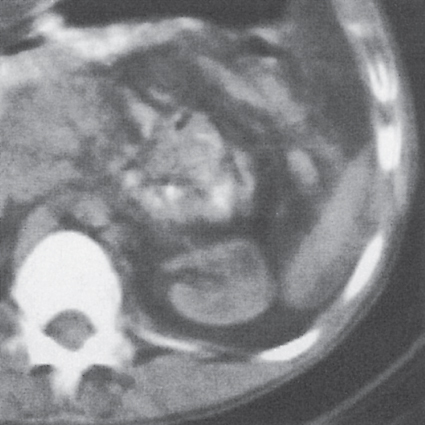

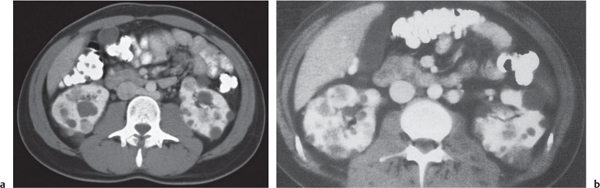

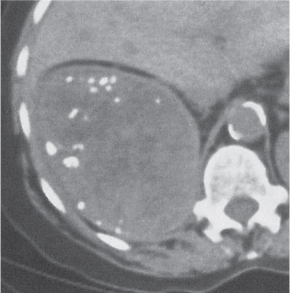

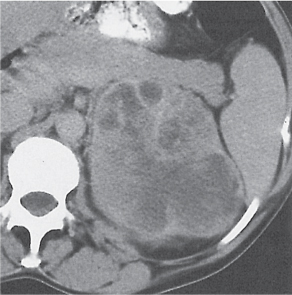

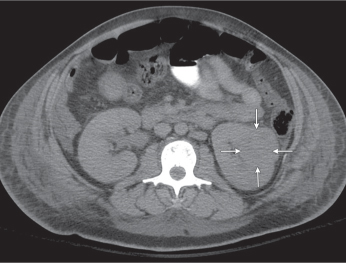

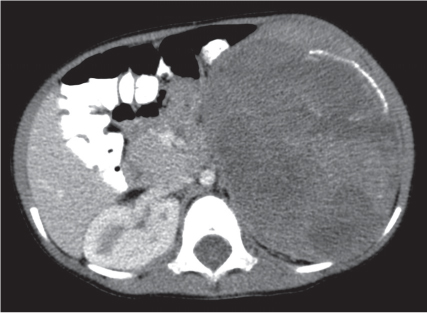

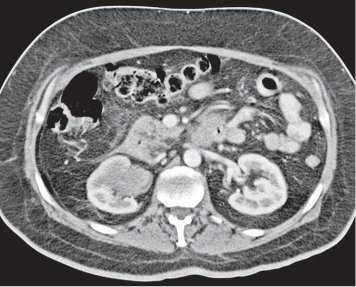

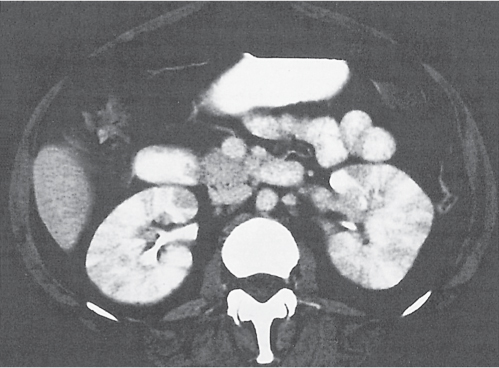

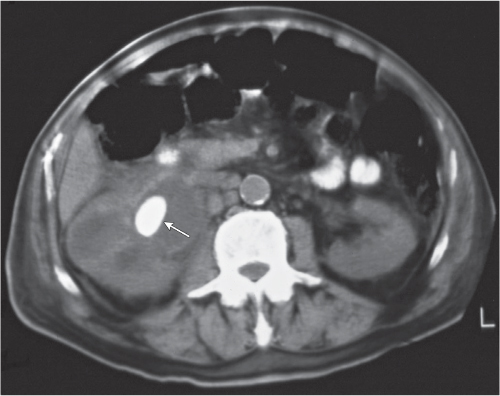

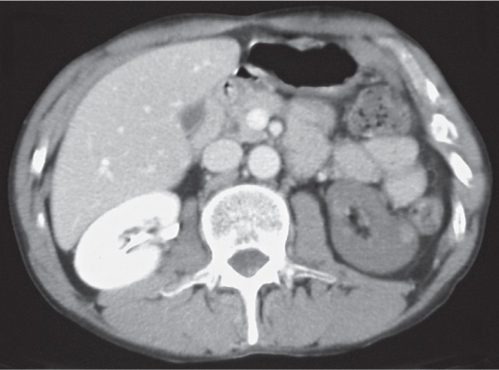

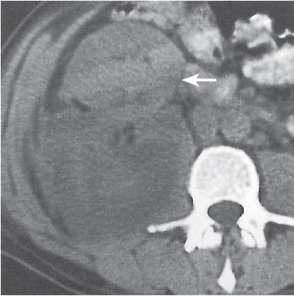

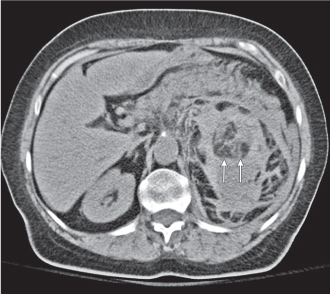

Fig. 27.13a, b

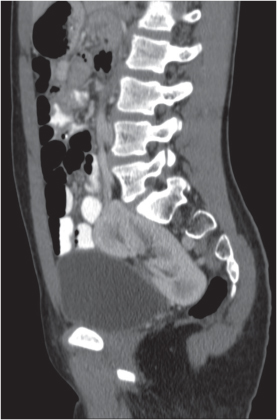

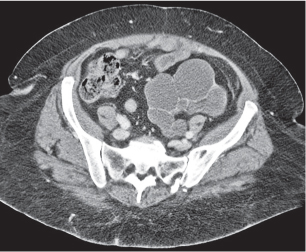

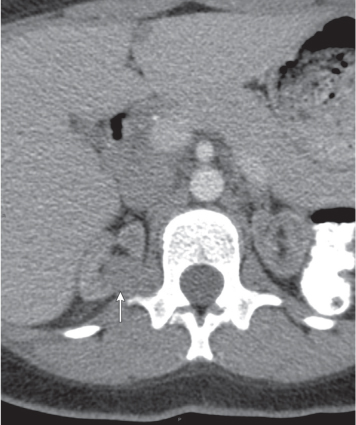

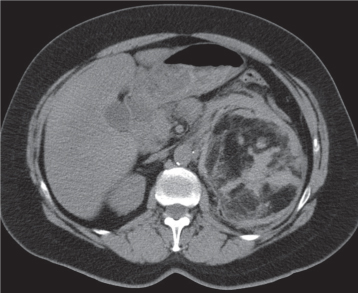

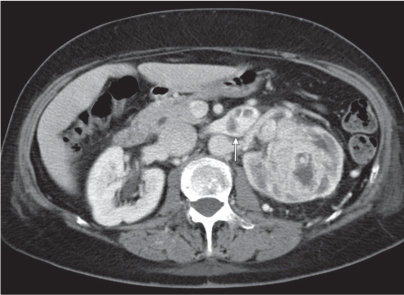

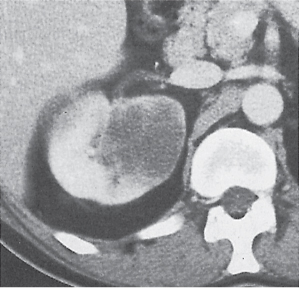

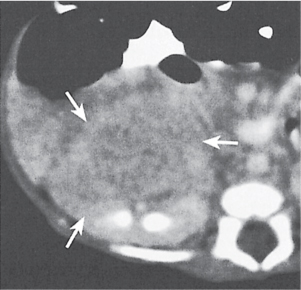

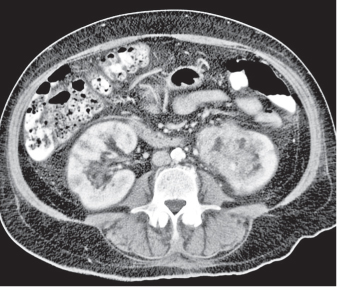

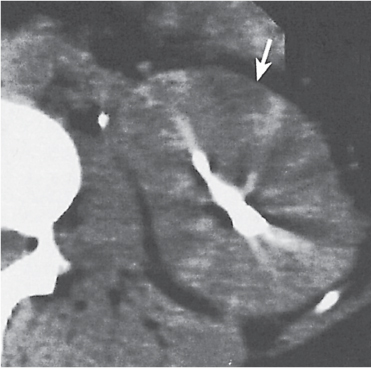

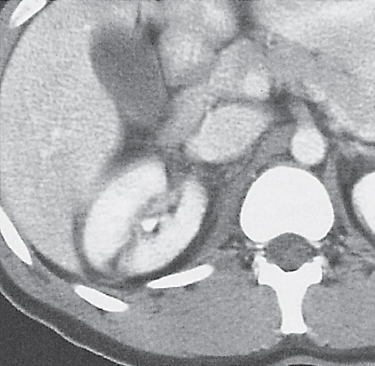

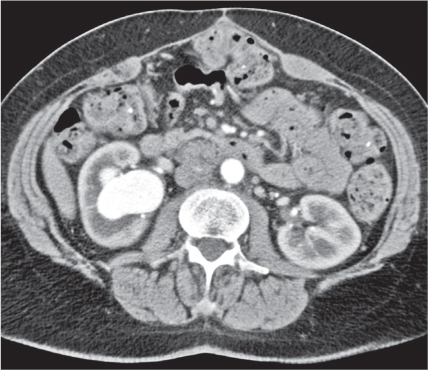

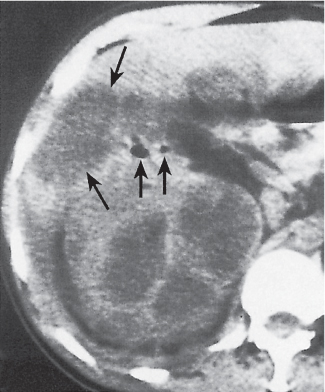

Fig. 27.14 |

Malpositioned kidneys are readily located and identified as functioning renal parenchyma after contrast enhancement. |

In horseshoe kidneys , the lower poles of both kidneys are fused by a parenchymal or fibrous isthmus across the midline at L4–L5 between the aorta and inferior mesenteric artery. The long renal axis is medially oriented, and renal pelvises and ureters are situated anteriorly. Upper pole fusion is rare (10%). Complications include hydronephrosis secondary to ureteral pelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, renal calculi, infection, and vesicoureteral reflux.

In longitudinal ectopy , the kidney is mal-positioned in any location from the thorax to the sacrum. Pelvic kidney is the most common location and frequently associated with vesicoureteral reflux, hydronephrosis, hypospadia, and contralateral renal agenesis. In crossed ectopy , the malpositioned kidney is commonly fused with the contralateral kidney. A large kidney with usual outline and two collecting systems on one side and an absent kidney on the contralateral side are diagnostic.

In renal fusion , the fused kidneys are located in the midline and may assume the shape of a horseshoe, disk, or pancake. Ureteral obstruction by aberrant arteries is frequently associated.

In renal malrotation , the collecting system is usually positioned anteriorly.

Differential diagnosis: A malpositioned kidney may also be caused by a large adjacent mass. |

Renal duplication

Fig. 27.15 |

Two separate renal sinuses and pelvises are seen, separated by a parenchymal bridge.

Upper pole moiety is subject to obstruction and may simulate an upper pole mass on excretory urography when completely obstructed. Hydronephrosis and hydroureter of the obstructed upper collecting system is readily diagnosed by CT. Lower pole moiety is subject to vesicoureteral reflux. |

In complete renal and ureteral duplication, the ureter draining the upper system inserts ectopically medial and below the orthotopic ureter into the bladder trigonum or urethra and may be associated with an ectopic ureterocele.

Other congenital renal anomalies are partial duplication, supernumerary kidney, and renal hypoplasia or agenesis. |

Renal sinus lipomatosis/fibrolipomatosis

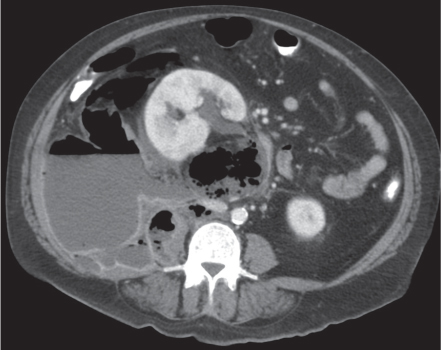

Fig. 27.16 |

Extensive proliferation of fat in the renal sinus associated with loss of renal parenchyma is characteristic. It may result in concentric encroachment of the renal collecting system (trumpetlike pelvocaliceal system on urography), but without obstruction. |

Etiology: (1) normal increase of sinus fat with aging and in obesity; (2) vicarious proliferation of sinus fat with renal atrophy of any cause; (3) fibrolipomatosis induced by extravasation of urine into the renal sinus (e.g., in chronic prostatism). |

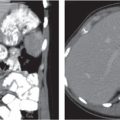

Hydronephrosis

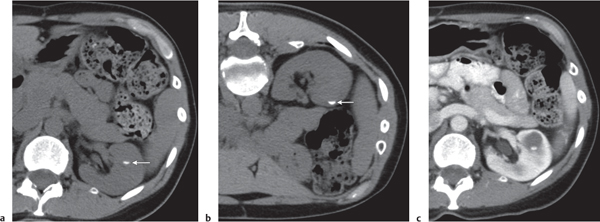

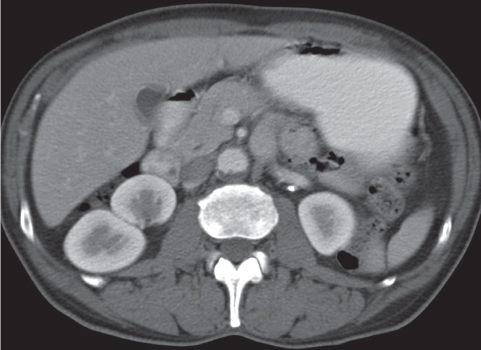

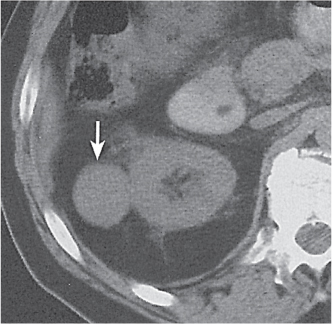

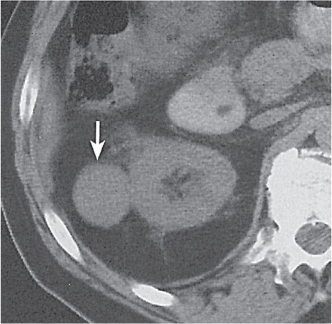

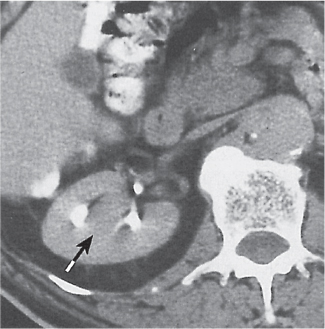

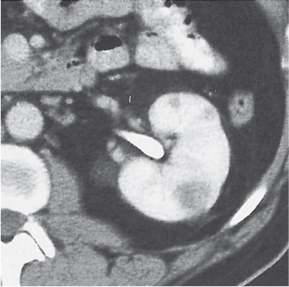

Fig. 27.17a, b

Fig. 27.18 |

Dilated collecting system evident as water-density structure within normal or enlarged kidney on nonenhanced images. High-density urine in obstructed system suggests pyonephrosis. After enhancement, a persistent nephrogram and delayed and decreased contrast medium excretion are characteristic. In long-standing obstruction, the kidney appears as a fluid-filled cyst with a thin rim of solid renal tissue draped around it. |

Early hydronephrosis can be differentiated from an extrarenal pelvis and postobstructive uropathy by the persistent nephrogram and delayed urinary contrast material excretion after contrast enhancement.

Level of obstruction can easily be identified with CT by following the dilated collecting system and ureter to the point of obstruction. Nonopaque calculi have a CT density of at least 50 HU and can therefore be differentiated from soft tissue lesions that have a lower density. Freely mobile filling defects in the collecting system other than renal calculi include blood clots and fungus balls. |

Renal cyst

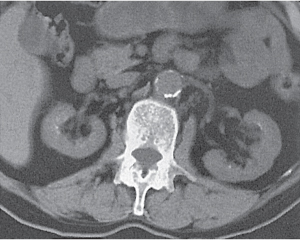

Fig. 27.19

Fig. 27.20

Fig. 27.21 |

Solitary or multiple sharply delineated, homogeneous lesions of near-water density (0–20 HU). Wall either very thin or not detectable when projecting beyond the renal outline. No contrast enhancement. Hemorrhagic cysts may demonstrate a fluid–fluid level or hematocrit effect due to settling of red blood cells. The Bosniak classification is commonly used for the CT assessment of cystic renal lesions (see Table 27.1). |

Most common renal mass in adults. Higher than water attenuation values in a renal cyst are found with hemorrhage into the cyst, contrast material leakage into the cyst (caused by either communication with the collecting system or diffusion), calcification of the cyst wall or the cyst content (milk of calcium or calcium carbonate), high protein content of cyst fluid, and infection. Partial volume averaging with normal adjacent renal parenchyma (e.g., in cysts smaller in diameter than the CT slice thickness) also results in a higher displayed attenuation value of the cyst. |

Parapelvic cyst (renal sinus cyst) |

Features of a benign renal cyst, but located adjacent to the renal sinus. Differentiation from an ectatic renal pelvis may require IV contrast administration demonstrating lack of enhancement of the cyst. |

Occurs frequently in the fifth and sixth decade of life and is almost always asymptomatic. Very rare complications may include obstructive caliectasis and renal vascular hypertension due to compression of renal arteries. |

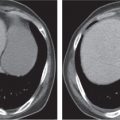

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)

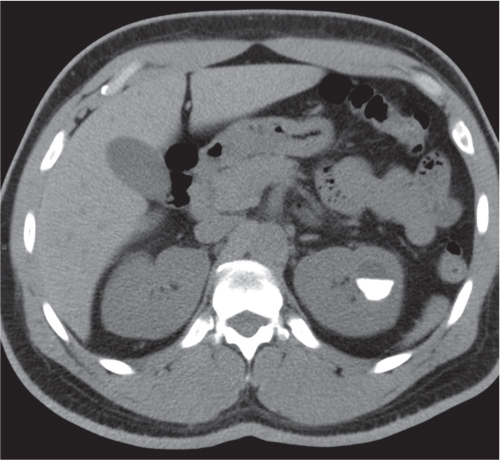

Fig. 27.22

Fig. 27.23 |

Bilateral, often markedly enlarged kidneys with lobulated contours but often not symmetrically involved. Multiple cysts of different sizes cause splaying and distorting of the collecting system and may demonstrate varying densities due to blood products of different ages. Unilateral involvement is exceedingly rare. |

Also referred to as adult polycystic kidney disease. Cysts are often also present in the pancreas, spleen, and lungs. Progressive renal failure and hypertension are usually evident in the fourth decade but occasionally as early as childhood or young adulthood. |

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) |

Symmetric, slightly enlarged kidneys with numerous tiny cysts (usually 1–2 mm, occasionally larger but always < 1 cm). They represent abnormally proliferated and dilated collecting tubules and do not produce calyceal or renal pelvis distortion. After IV contrast material administration, a prolonged and increasingly hyperintense, heterogeneous nephrogram is seen with delayed and decreased urinary contrast medium excretion. |

Also referred to as infantile polycystic kidney disease. Occurs in neonates and children younger than 5 y. Associated with dilated bile ducts, periportal fibrosis, and pancreatic fibrosis. Neonatal death occurs in up to 50% of cases from pulmonary hypoplasia with long–term survival improving substantially after the newborn period. |

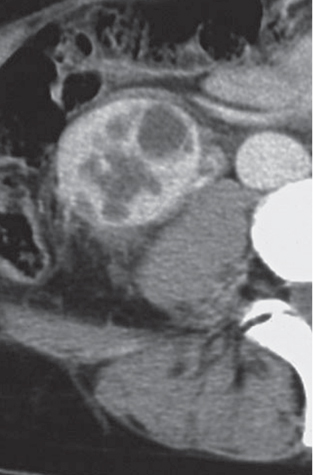

Multicystic dysplastic kidney

Fig. 27.24 |

Unilateral involvement consisting of a small or large single-chamber or multiloculated cystic mass, often with central or peripheral calcifications. No functional renal parenchyma is detectable after contrast administration (unlike multilocular cystic nephroma and unilateral polycystic kidney disease). |

Frequent cause of palpable abdominal mass in an otherwise healthy infant or child resulting from failed fusion of the metanephros and ureteric bud. Compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral kidney is usually present, often with an element of ureteropelvic obstruction. |

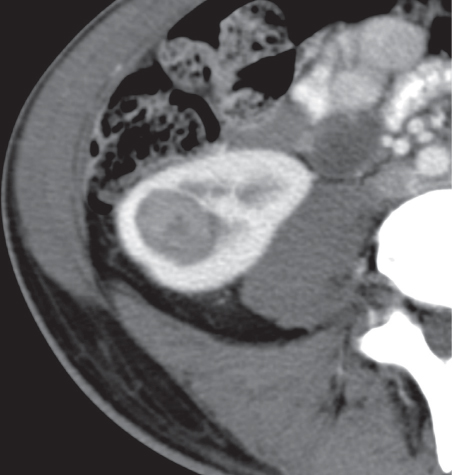

Multilocular cystic nephroma (multilocular cystic renal tumor)

Fig. 27.25

Fig. 27.26 |

Single or multiple fluid-filled cysts measuring up to 10 cm, often replacing an entire renal pole (usually lower pole). Cysts are often separated by thick septa and sharply demarcated from the normal renal parenchyma. Peripheral and central calcifications of circular, stellate, flocculent, or granular nature in up to 50% of cases. Cyst wall and septations enhance after contrast administration. |

Occurs in children younger than 5 y (M:F = 3:1) and in 40- to 70-y-old adults with strong female predominance. On ultrasound, multiple cystic masses separated by highly echogenic septa are evident.

Cystic Wilms tumor and cystic renal cell carcinoma must be differentiated. Nodular thickening of the cyst wall and/or septa may be the clue for a malignancy. |

Medullary cystic disease

Fig. 27.27 |

Bilateral small kidneys with multiple small medullary cysts that do not extend to the renal margins are characteristic. |

Rare, in the majority of cases inherited, disorder manifesting itself in adolescents and young adults with progressive renal failure. |

Medullary sponge kidney |

Bilateral, unilateral, or segmental ectasia of the tubules in often enlarged papilla presenting after IV contrast material administration as tubular structures radiating from the calyx into the papilla. In approximately half of the cases, small calculi measuring up to 5 mm are clustered in the ectatic tubules of the papilla. |

Usually an incidental finding in asymptomatic young to middle-aged adults.

Differential diagnoses include medullary nephrocalcinosis (no ectatic tubules, calcifications beyond pyramids), renal TB (calcifications larger and more irregular), and papillary necrosis (partial or total papillary slough). |

Acquired cystic disease of dialysis

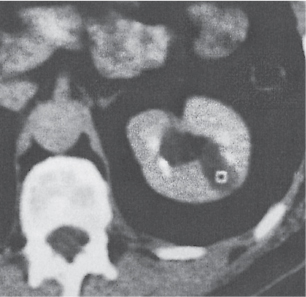

Fig. 27.28 |

Small kidneys with largely preserved contours, as the cysts varying from 0.5 to 2 cm in diameter are mostly intrarenal. Complications include hemorrhage and development of renal adenomas and carcinomas. |

Up to 50% of patients on chronic dialysis. Incidence increases with time, particularly after the third year. Cystic disease may regress after renal transplantation. Renal carcinomas are associated in 7% of patients. |

Von Hippel–Lindau disease

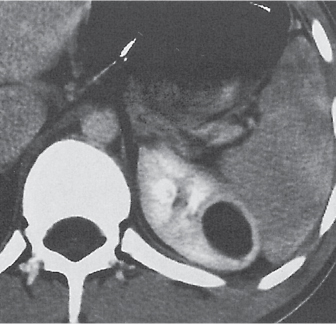

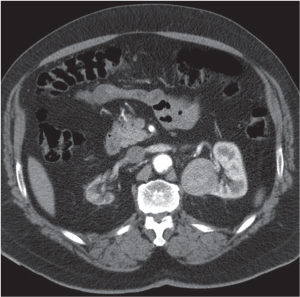

Fig. 27.29a, b |

Combination of multiple renal cysts and solid tumors (carcinomas, adenomas, and hemangiomas) characteristic. Renal carcinomas are often small, < 2 cm in size, and may occur within the cysts themselves. Involvement usually bilateral and multicentric. |

Inherited (autosomal dominant) neurocutaneous dysplasia complex with onset in the second to third decade. Retinal angiomatosis, cerebellar and spinal hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytomas, pancreatic tumors and cysts, hepatic adenomas, and hemangiomas may be associated. |

Renal pseudotumor

Fig. 27.30 |

Focal enlargement of normal renal parenchyma simulating a tumor on other imaging studies. On CT, the mass has all the characteristics of normal renal tissue, including enhancement after IV contrast medium administration. |

These anomalies include:

Fetal lobulations: cortical bulges centered over corresponding calyces

Dromedary hump: in the midportion of the left kidney due to prolonged pressure by the spleen during fetal development

Column of Bertin: focal hypertrophy of the septal cortex in the midportion of the kidney causing deformation of the adjacent calyces and infundibula

Hilar lip: supra- and infrahilar cortical bulge above and below the renal sinus

Nodular compensatory hypertrophy: hypertrophied normal renal tissue secondary to focal renal scarring |

Renal adenoma

Fig. 27.31 |

Solitary or, less commonly, multiple cortical nodules measuring by definition < 3 cm in diameter. CT appearance is similar to renal cell carcinoma of the same size, that is, homogeneous and minimally hypodense to isodense on the precontrast and markedly hypodense on the postcontrast examination. |

Most common cortical lesion at autopsy. May be a precursor of a renal cell carcinoma.

Metanephric adenoma typically presents as a slightly hypoattenuating mass with little enhancement and occasionally small calcifications.

Juxtaglomerular tumor (reninoma) is indistinguishable on CT from a renal adenoma but presents clinically with marked hypertension. |

Oncocytoma

Fig. 27.32 |

Solid 1- to 14-cm mass that is sharply separated from the cortex, does not invade the collecting system, and is rarely calcified. A central stellate, nonenhancing scar of lower density secondary to infarction and hemorrhage is characteristic but seen only in larger lesions (33%). After contrast administration, a homogeneous contrast enhancement that is only slightly less dense than the renal parenchyma is common, but occasionally poor tumor enhancement is found. |

Seen in middle-aged patients, with a slight male predominance. Histologically, this benign tumor may be mistaken for a well-differentiated renal cell carcinoma with oncocytic features. |

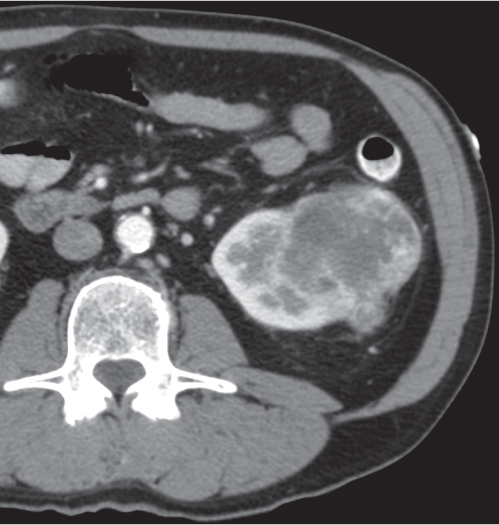

Angiomyolipoma (renal hamartoma)

Fig. 27.33

Fig. 27.34

Fig. 27.35

Fig. 27.36 |

Single or multiple renal masses ranging from 1 to 8 cm in diameter with attenuation values ranging from −100 HU (fat) to +150 HU (calcifications). Scattered punctate calcifications are rare (6%). Demonstration of intratumoral fat (≤ 20 HU) is characteristic, even if the tumor is composed mainly of vascular tissue, muscle, and hemorrhage, resulting in CT values > 20 HU in most parts of the lesion. After contrast administration, inhomogeneous tumor enhancement sparing only the fatty tissue and areas of necrosis is characteristic. |

Occurs as an isolated lesion in middle-aged women (4:1 female predominance) or as renal manifestation in tuberous sclerosis ( Figs. 27.37, 27.38 ) , where tumors are commonly multiple and bilateral. Although the CT diagnosis of angiomyolipomas is highly suggestive by the demonstration of fatty tissue, occasionally rare tumors such as renal lipomas, liposarcomas, and Wilms tumor containing small amounts of fatty tissue cannot be absolutely excluded. Renal cell carcinomas may occasionally also contain fatty tissue and calcifications. |

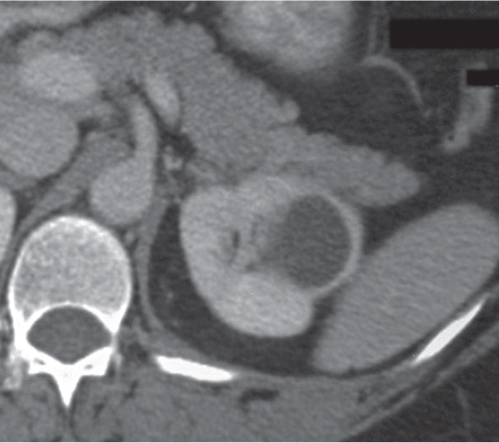

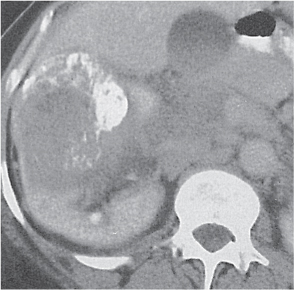

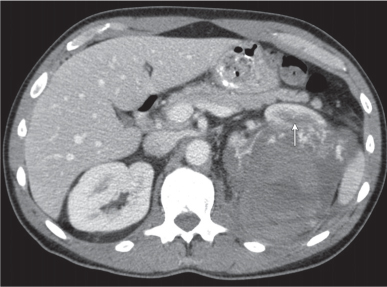

Renal cell carcinoma

Fig. 27.39

Fig. 27.40

Fig. 27.41

Fig. 27.42 |

Homogeneous or heterogeneous, irregularly shaped, and poorly demarcated mass producing an irregular or lobulated renal contour and distortion of the collecting system. The attenuation is slightly less than that of normal renal parenchyma. Less commonly, the tumor is isodense or hyperdense (e.g., after recent intratumoral hemorrhage and tumor calcifications) on precontrast scans. Rarely, renal cell carcinomas are largely to completely cystic. Calcifications occur in 20% of patients and usually are central and amorphous or peripheral and curvilinear in cystic renal cell carcinomas. Intratumoral metaplasia into fatty marrow occurs occasionally in larger lesions. After contrast administration, the nonnecrotic parts of the tumor demonstrate an unequivocal increase in density, that is, less than the surrounding normal renal parenchyma, making the tumor more apparent on contrast-enhanced scans. Tumor spread to the perinephric fat, local lymph nodes and vessels, and adjacent organs can also be depicted in more advanced stages. |

Most common malignant renal tumor, accounting for > 80% of all renal primaries. Twice as frequent in men as women and rare in patients younger than 40 y (peak age 55 y). Gross hematuria (60%) and flank pain (50%) are the most common clinical presentation. Bilateral involvement in 2% of cases. CT is most valuable for both diagnosing and staging.

Robson staging system:

Stage I: tumor confined to kidney

Stage II: tumor spread to perinephric fat

Stage IIIA: tumor spread to renal vein or inferior vena cava (IVC)

Stage IIIB: tumor spread to local lymph nodes

Stage IIIC: tumor spread to both local vessels and lymph nodes

Stage IVA: tumor spread to adjacent organs (except ipsilateral adrenal)

Stage IVB: distant metastases |

Medullary renal tumor |

Large, ill–defined mass centered in the renal medulla with extension into the renal sinus and cortex. Contrast enhancement may be heterogeneous due to varying amounts of hemorrhage and necrosis. Renal medullary carcinoma and collecting duct carcinoma are differentiated. |

Renal medullary carcinoma ( Fig. 27.43 ): Highly aggressive malignant tumor of epithelial origin occurring almost exclusively in adolescent and young adult blacks with sickle cell trait (not with hemoglobin SS sickle cell disease), with mean survival rate of 15 weeks from diagnosis. Presents as large, ill-defined, heterogeneous mass centered in the renal medulla with extension into the renal sinus and cortex and nonuniform contrast enhancement.

Collecting duct carcinoma (Bellini) ( Fig. 27.44 ): High-grade, infiltrative neoplasm centered in the renal medulla with renal sinus invasion, cortical extension, and metastases in 40% at presentation. Mean age 55 y (range 13–80 y). |

Renal transitional cell carcinoma

Fig. 27.45

Fig. 27.46 |

Small tumors are often not detectable on precontrast scans but present as a smooth or irregular (frondlike) filling defect in the opacified renal pelvis. Contrast enhancement of the tumor itself is only subtle (8–40 HU precontrast, up to 55 HU postcontrast). Larger tumors cause hydronephrosis, obliterate the peripelvic fat, and invade the renal parenchyma and vessels, but they do not affect renal contour. Tumor calcifications are very rare. |

Most common uroepithelial tumor (85%), multiple in one third of the cases. Majority (70%) of patients are men older than 60 y. Hematuria occasionally associated with flank pain is the most common clinical presentation.

Squamous cell carcinoma (15%) is frequently associated with chronic leukoplakia. Renal calculi are present in 50% of patients, and tumor calcification occurs in 10%. The prognosis is very poor, as the tumor is usually well advanced at the time of diagnosis.

Nephrogenic adenoma is an uncommon benign metaplastic response to a urothelial injury or prolonged irritation presenting as a papillary or polypoid filling defect in the renal pelvis. Malignant transformation is rare. |

Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma)

Fig. 27.47

Fig. 27.48 |

Large, inhomogeneous mass often with central hypodense areas representing cysts, necrosis, and/or hemorrhage. Calcifications are unusual. An enhanced rim of compressed renal parenchyma (pseudocapsule) is frequently present. Rarely, a large cyst with irregularly thickened wall and septa is the dominant feature. Tumor invasion into the renal vein occurs in one third of cases. In adults, the tumor is virtually indistinguishable from a renal cell carcinoma, except for a large central necrosis, which is more typical for the latter.

Staging:

1. Tumor limited to kidney

2. Local extension into perirenal tissue, renal vein, and/or para-aortic lymph nodes

3. Not totally resectable (peritoneal implants, distant lymph node metastases in abdomen and pelvis)

4. Hematogenous metastases and/or lymph node metastases above diaphragm

5. Bilateral renal involvement |

Most often in children between 1 and 5 y of age presenting usually with an asymptomatic abdominal mass. Hypertension, hematuria, aniridia, and hemihypertrophy (Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome) may be associated. Metastases to lungs are frequent, less common to liver and lymph nodes. In contrast to neuroblastomas, bone metastases and tumor calcifications are rare.

Mesoblastic nephroma ( Fig. 27.49 ): Benign intrarenal mass in neonates with CT appearance similar to Wilms tumor, but without venous extension.

Nephroblastomatosis: Multiple nodules of primitive metanephric tissue. Benign condition with unilateral or bilateral renal involvement predisposing to the development of a Wilms tumor. |

Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney |

Centrally located, heterogeneous renal mass with indistinct borders and frequent central necrosis. Tumor lobules may be outlined by linear calcifications. Subcapsular crescent-shaped hematoma is associated in half of the cases. |

Most aggressive renal neoplasm in childhood, typically occurring before the age of 2. May be associated with primary brain tumor of neuroectodermal origin (e.g., medulloblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor [PNET]). |

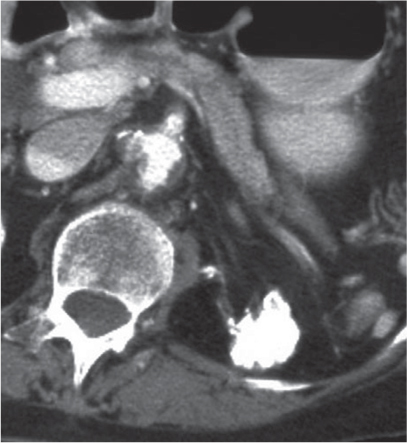

Renal lymphoma

Fig. 27.50

Fig. 27.51

Fig. 27.52 |

Homogeneous infiltrate or mass, slightly hypodense on pre-contrast and markedly hypodense on postcontrast scans. Bilateral involvement common.

Manifestations:

1. Renal enlargement caused by diffuse infiltration with maintenance of the normal renal contour

2. Multiple nodules

3. Solitary intrarenal mass

4. Retroperitoneal disease extending into the renal pelvis

5. Compression of the collecting system or vascular structures causing hydronephrosis or a nonfunctioning kidney After contrast enhancement, the lymphomatous tissue increases only slightly in attenuation. |

Late manifestation of the disease, caused by hematogenous spread or direct extension from adjacent pararenal lymphoma. Absence of clinical symptoms in > 50% of patients. Leukemia can also produce bilateral renal enlargement and intrarenal masses ( Fig. 27.53 ) . |

Renal metastases

Fig. 27.54

Fig. 27.55

Fig. 27.56 |

Solitary renal mass or, more commonly, multiple nodules of varying sizes. Metastases are usually small and do not distort the renal contour or the collecting system. |

Most common renal malignancy at autopsy, but infrequently diagnosed antemortem. Lung and breast carcinomas are the most common primaries, but stomach, colon, pancreas, cervix, and gonads are other sites of origin. |

Mesenchymal renal tumors (benign or malignant)

Fig. 27.57

Fig. 27.58 |

No characteristic features except for the demonstration of fatty tissue in lipomas and liposarcomas (see also angiomyolipoma) and the irregular peripheral contrast enhancement proceeding centrally in hemangiomas. |

Very rare.

Ossifying renal tumor of infancy presents as benign calcified (80%) filling defect in the renal pelvis with poor enhancement on CT. |

Renal abscess

Fig. 27.59 |

Cavitating mass with thick, irregular wall and liquefied center of decreased density simulating a necrotic neoplasm. After contrast administration, the wall of the abscess enhances, whereas the liquefied central part of the abscess does not. Perinephric extension and thickening of the renal fascia are common. Demonstration of gas bubbles or a gas–fluid level within the mass is virtually diagnostic but only rarely present. |

The CT appearance of a renal abscess may be difficult to differentiate from a necrotic renal cell carcinoma. |

Pyelonephritis, acute

Fig. 27.60

Fig. 27.61

Fig. 27.62

Fig. 27.63 |

Renal involvement may be unilateral or bilateral, diffuse or, more commonly, focal. Findings depend on the severity of the infection. Size of the involved kidney is normal to diffusely enlarged. On the precontrast scan, the affected renal area is isodense to slightly hypodense and poorly marginated. Occasionally, inflammatory (edematous) changes in the perinephric fat and mild thickening of both the renal fascia and the walls of the renal pelvis and calyces can be appreciated. Slight dilation of the renal pelvis and ureter is frequently also present. After contrast enhancement, a patchy inhomogeneous enhancement is evident that is, however, less than in the nonaffected part of the kidney. These hypoattenuating zones extending from the papilla into the cortex are typically wedge-shaped in the nephro-graphic phase. Other findings include poor corticomedullary differentiation after an intravenous material bolus and a striated nephrogram that may persist for an extended period of time. |

Most commonly an ascending Escherichia coli infection presenting with fever, chills, and flank pain. Patients with altered host resistance (e.g., diabetes, immunosuppression), mechanical or functional ureteral or bladder outlet obstruction, including stones, and chronic catheterization are predisposed. Hematogenous route of infection accounts for 15% of cases. May occur at any age, with marked female prevalence.

Acute focal pyelonephritis is also referred to as renal phlegmon.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis( Fig. 27.64 ) is a life-threatening necrotizing infection usually in diabetics. Mottled areas of gas extending radially along the pyramids are diagnostic. Gas may also be found in the perinephric and retroperitoneal space and occasionally the renal veins.

Chronic atrophic pyelonephritis is usually associated with vesicoureteral reflux. Calyceal dilation with overlying cortical scarring, preferentially located in the polar regions, is characteristic. |

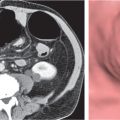

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis

Fig. 27.65 |

Diffuse or, much less commonly, focal renal enlargement with poor or no contrast excretion (global or focal). Solitary or multiple nonenhancing masses with lobulated contours and frequent extension into the perinephric space and occasionally adjacent organs are a typical presentation. A large central calculus and a pyonephrotic collecting system that may be distorted or partially replaced by the inflammatory masses are characteristically present. |

Chronic suppurative granulomatous infection in a chronically obstructed kidney (usually due to nephrourolithiasis), occasionally by stricture or tumor. Most cases are associated with Proteus infections. All ages are affected (peak: fourth to fifth decade), with a 3:1 female predominance. Involvement may be diffuse (90%) or focal (tumefactive form). |

Renal trauma

Fig. 27.66

Fig. 27.67

Fig. 27.68 |

Intrarenal (renal contusion): Focal area of decreased nephrogram with poor opacification of corresponding calyces.

Subcapsular: Lenticular defect with flattening of the adjacent renal parenchyma. On precontrast scan, the hematoma is usually hypodense, but immediately after injury, occasionally a higher density than the surrounding kidney may be found. After contrast administration, the density of the nonenhancing hematoma is always markedly decreased compared with the normal renal parenchyma. |

Renal biopsies, extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy, and trauma are common causes. Spontaneous hematomas in the absence of bleeding diathesis should raise suspicion of an underlying malignancy or an angiomyolipoma.

Classification of renal trauma:

1. Limited to renal parenchyma: renal contusion or subcapsular hematoma without disruption of calyceal system and renal capsule.

2. Complete laceration or renal fracture with involvement of renal capsule and/or calyceal system.

3. Shattered kidney (multiple separate renal fragments) or injury to the renal vascular pedicle. |

Renal infarction

Fig. 27.69

Fig. 27.70 |

Regional: Peripheral wedge-shaped areas of decreased density, typically between calyces and most obvious after contrast administration.

Total (renal artery occlusion): After contrast enhancement, a thin subcapsular rim of high density caused by capsular collaterals to the outer cortex surrounds a central zone of diminished density. |

Caused by trauma (avulsion of the renal artery), embolism, thrombosis, and renal vein thrombosis. The latter is diagnosed by an enlarged renal vein containing a filling defect on enhanced CT scans. An exaggerated and prolonged corticomedullary differentiation may be evident in the acute stage. |

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Fig. 27.71 |

Well-defined intrarenal mass lesion with attenuation values similar to the aorta or IVC before and after contrast administration. Large feeding and draining vessels are also characteristic. Curvilinear calcifications are rare. |

Congenital or acquired (trauma, biopsy, spontaneous rupture of an aneurysm, very vascular malignant neoplasm).

Intrarenal aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm of the renal artery may present similarly except for the absent feeding and draining vessels. |