28 Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands are small retroperitoneal structures readily identified by computed tomography (CT). They are located lateral to the spine at the level of the eleventh and twelfth rib and embedded in the perinephric fat that separates the kidney from the anterior (Gerota) and posterior (Zuckerkandl) renal fascia. On CT, normal adrenals extend 2 to 4 cm in a caudocranial direction and display a variety of shapes. The limbs of the adrenal glands have a uniform thickness of 5 to 8 mm with straight or concave margins. A limb thickness exceeding 10 mm is highly suggestive of adrenal disease with the exception of sites where two limbs converge.

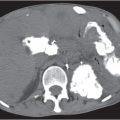

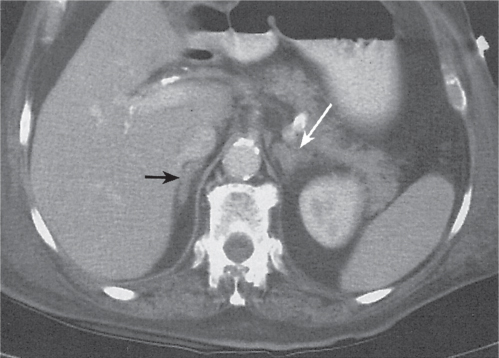

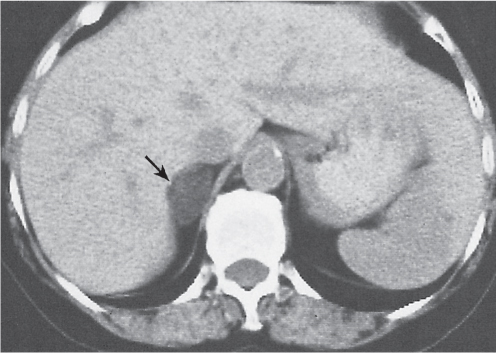

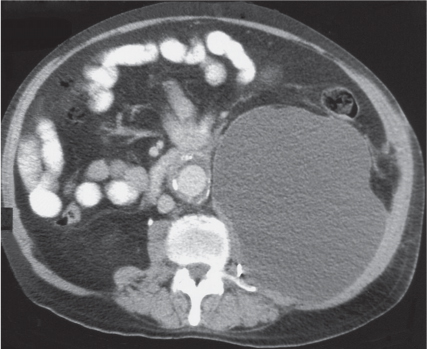

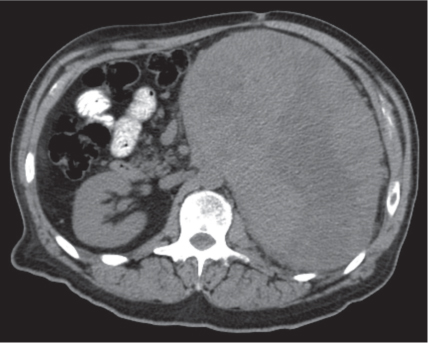

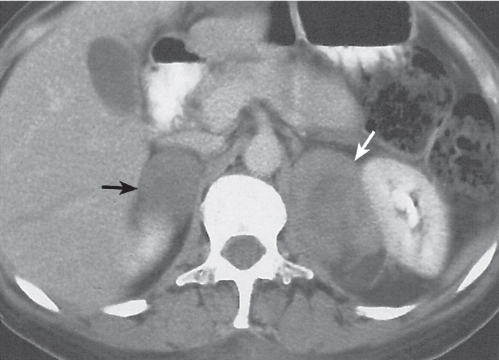

On axial images, the right adrenal gland usually has an oblique linear configuration, paralleling the crus of the diaphragm, and rarely an inverted V, an inverted Y, an X, H, or triangular shape (Fig. 28.1). The right adrenal usually lies 1 to 2 cm superior to the upper pole of the right kidney and immediately posterior to the inferior vena cava. The right adrenal gland is also sandwiched between the right crus of the diaphragm medially and the right lobe of the liver laterally.

The left adrenal most often has an inverted V or an inverted Y shape and occasionally assumes a triangular shape on axial images (see Fig. 28.1). The left adrenal lies lateral to the crus of the left diaphragm and posterior and slightly medial to the tail of the pancreas and the stomach. The lower portion of the left adrenal may be in contact with the anteromedial aspect of the upper pole of the left kidney. The left adrenal is generally slightly caudal to the right adrenal.

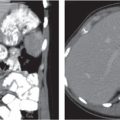

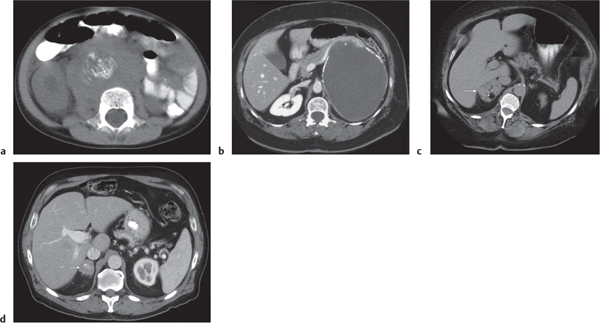

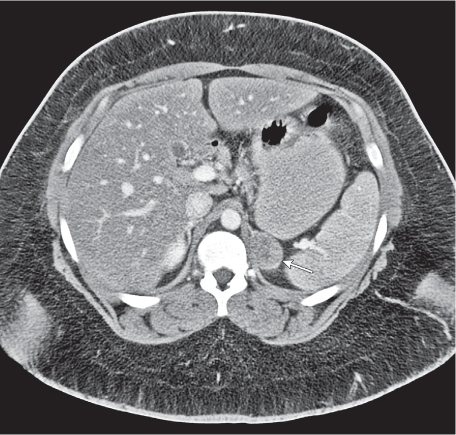

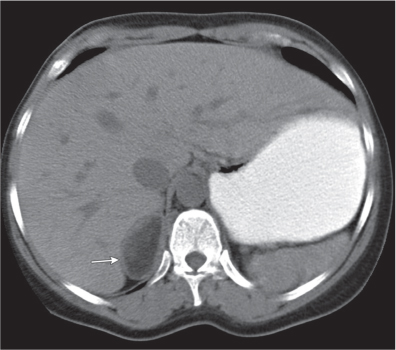

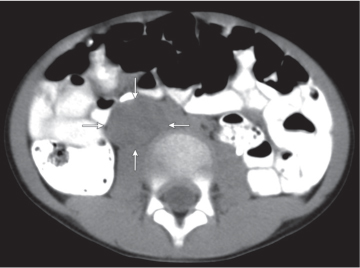

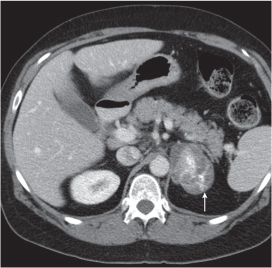

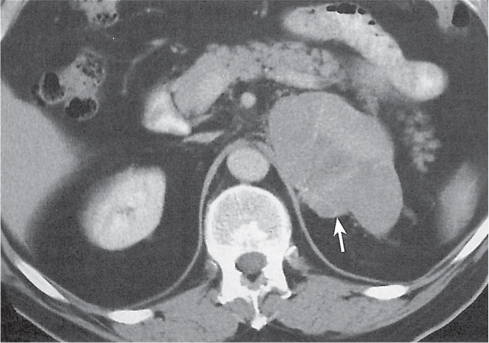

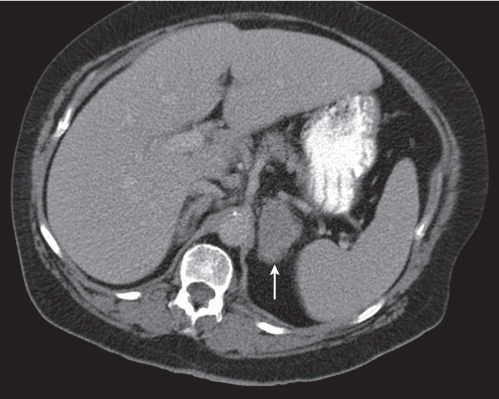

Differentiating between a benign adrenal adenoma, an incidental finding in 2% of the general population and an adrenal metastasis, the overall fourth most common metastatic site in the body, is a great challenge in the staging of a tumor patient. Adrenocortical adenomas typically measure less than 4 cm in diameter (average size about 2 cm), enhance only mildly but uniformly after contrast material administration, and depict a relatively rapid contrast washout on delayed scans (Fig. 28.2). Adrenal metastases frequently measure often more than 3 cm in diameter, may be inhomogeneous, particularly when larger, tend to enhance more and less uniformly than adenomas, and demonstrate a relatively slow contrast washout. A contrast washout of 50% at 10 minutes after injection is suggestive of a benign adenoma. However, because of the substantial variability in the vascularity of metastases ranging from hypovascular to hypervascular, benign and malignant lesions cannot reliably be differentiated based on their difference in contrast enhancement and washout rates. Adrenal adenomas contain intracytoplasmic lipids (steroids) to a varying degree. Depending on the amount of these lipids, the density of these lesions is accordingly decreased when compared with soft tissue masses not containing any fat. Therefore, on a nonenhanced scan, a uniform CT density of less than 20 HU in a solid lesion strongly suggests a benign adenoma. Fat suppression techniques in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appear even more useful for the differentiation between benign adrenal adenomas and metastases. The approach that appears most promising is the combined use of an in-phase/out-of-phase gradient echo technique. This chemical shift-imaging method allows assessment of the intracellular fat content. Benign adenomas containing intracytoplasmic lipids lose signal intensity on out-of-phase images, whereas metastases do not. However, adenomas that do not contain lipids in sufficient quantities and other benign masses cannot be differentiated from metastases with this technique. More recently, positron emission tomography (PET) scan has been shown to more accurately identify adrenal metastases when the primary tumor takes up F 18 fluorodeoxyglucose.

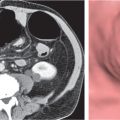

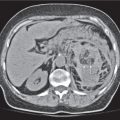

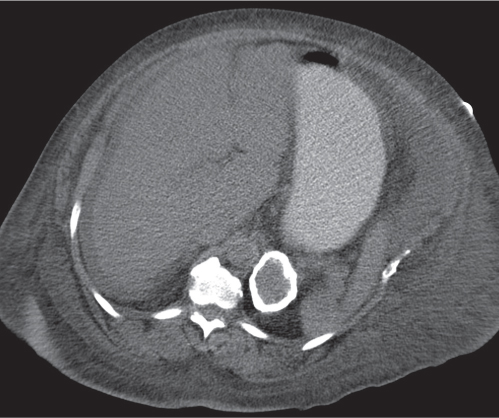

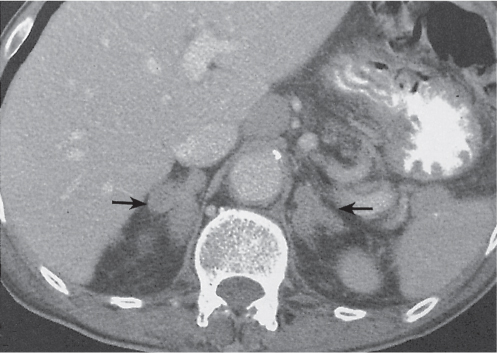

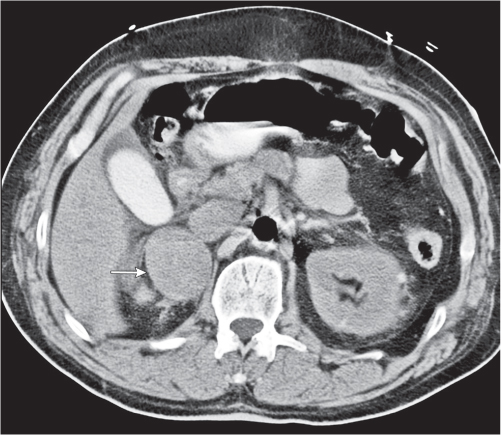

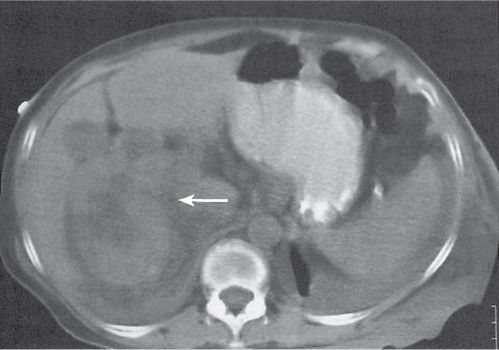

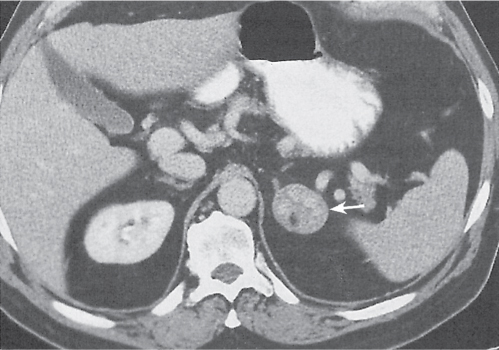

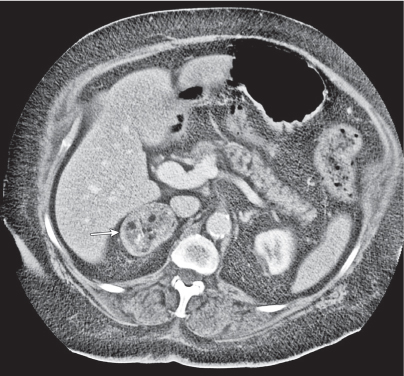

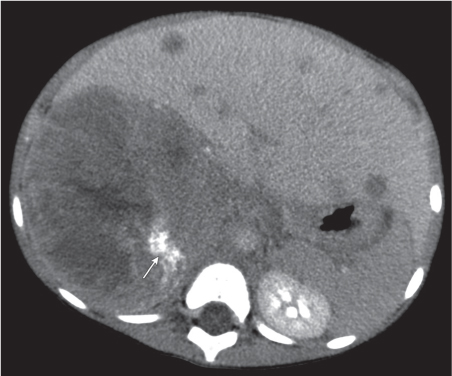

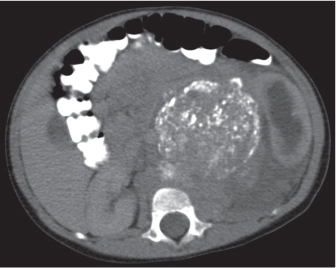

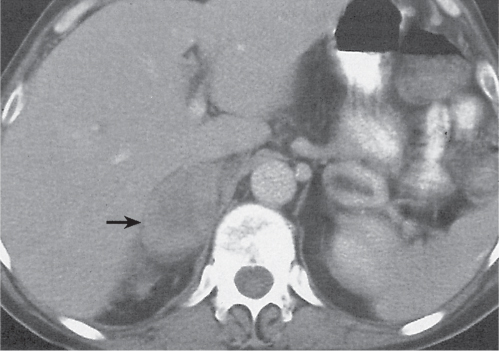

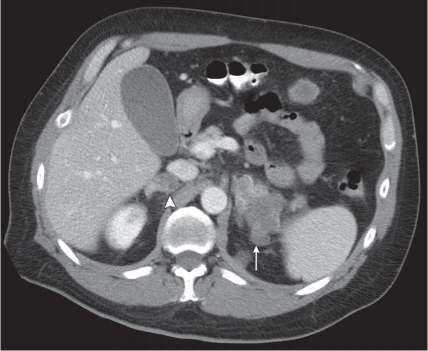

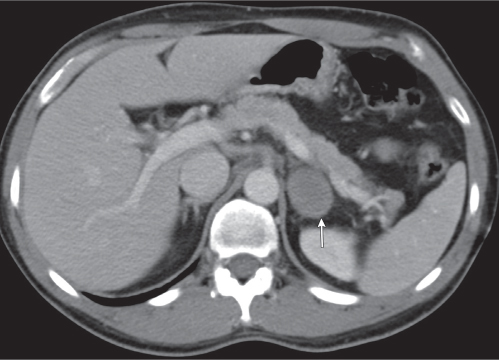

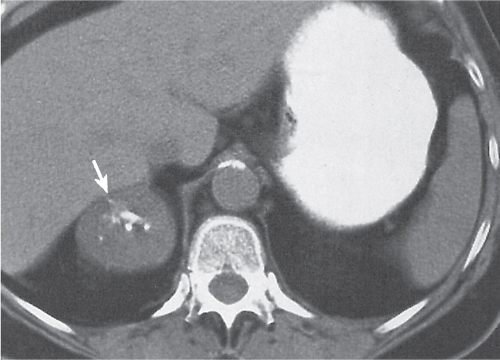

Adrenal calcifications are associated with tumors, hemorrhage, and infections. Tumor calcifications (Fig. 28.3) are very common in neuroblastomas (80%); not unusual in myelolipomas, pheochromocytomas, and adrenal carcinomas (about 20% each); and rare in cortical adenomas. Calcifications in adrenal hemorrhage (Fig. 28.4) and infections are late sequelae of the disease occurring usually 1 y or later after the insult. Adrenal hemorrhage may be traumatic or nontraumatic (e.g., neonatal stress, surgery, burns, hypotension with shock, pregnancy, hemorrhagic diathesis, coagulopathy, and anticoagulation therapy). Calcification in a hemorrhagic pseudocyst characteristically is curvilinear (“eggshell” calcification). Infections commonly associated with adrenal calcifications include tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, and Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (fulminant meningococcemia). Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage and infections with destruction of more than 90% of the adrenal cortex result in adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease).

The differential diagnoses of focal or diffuse adrenal enlargement are discussed in Table 28.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree