29 Soft-Tissue Lesions Caused by Overuse and Sports

Injuries of the hand caused by overuse and sports mostly involve muscles, tendons, and related structures. Common lesions are tenosynovitis of the extensor and flexor tendons, ruptured tendons, injuries to the anular and collateral ligaments and the metacarpophalangeal (MP) joints, especially the thumb, synovitis in the ulnar recess, and muscle injuries. Ultrasonography is very important in initial diagnosis, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is performed for further diagnostic precision of soft-tissue lesions. Associated osseous changes are rare and can be confirmed or excluded radiographically or with scintigraphy.

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

Overuse sports and occupational injuries are caused by chronic recurring or acute overload on tendons, tendon sheaths, ligaments, or muscles. They appear as nonbacterial inflammatory conditions with pain, swelling, a d functional restrictions, or as tears of tendons, ligaments, or muscles with a corresponding loss of function or stability. The pathogenesis of the different lesions listed in Table 29.1 varies.

|

Diagnostic Imaging

Patient’s history and clinical examination largely specify overuse and sports injuries so that sectional imaging may become necessary only in equivocal situations. Availability and economics support early application of high-resolution ultrasonography. MRI provides far more diagnostic information in soft-tissue lesions of the hand than does CT (Chapters 9 and 45). Radiographs of the affected area of the hand should always be acquired first to detect or exclude a rare involvement of the bone.

Disease Entities

Tendinosis and Tenosynovitis

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

The terms tendinosis and tenosynovitis, which are not strictly differentiated, describe lesions in the tendons and tendon sheaths that usually occur together.

Tendinosis may be a primary, idiopathic degenerative process or, more frequently, secondary to overuse or abnormalities of the surrounding tissues. This tendon abnormality is usually caused by repetitive microtrauma occurring during overload. If the microtraumas reach a certain extent, a repair processes sets in, which can be divided into three stages:

The inflammatory phase with vasodilatation, increased vascular permeability, and cell infiltration; clinical symptoms consist of swelling, hyperthermia, and erythema.

The proliferative phase with production of collagen and interstitial substances; this only occurs when overexertion ceases. If the overload continues, chronic inflammation arises with secondary fibrosis and adhesions. The immature repair tissue isweak and prone to injury.

The maturation phase completes the healing process with the production and longitudinal extension of stout bundles of collagen fibers.

The clinical appearance is dominated by pain on exertion and different degrees of swelling.

Tenosynovitis is characterized by an inflammatory irritation of the synovial tendon sheath accompanied by swelling, pain around the affected tendon sheath during pressure and extension, and a semiflexed, protective position of the finger. Nonrheumatic tenosynovitis usually rises as a result of chronic, repetitive overuse of tendons and tendon compartments associated with occupational and sporting activities. Predisposed areas are where tendons enclosed in sheaths run through osteofibrous tunnels. In contrast to tenosynovitis crepitans, there is no true inflammation.

Tendinosis and Tenosynovitis of the Extensor Tendons

Stenosing tenosynovitis (tenosynovitis) of the first extensor compartment is referred to as de Quervain disease. The approximately 2cm-long osteoligamentous tunnel of the first extensor compartment is formed by an osseous groove in the radial styloid process and the overlying extensor retinaculum. Stenosing Stenosing tenosynovitis is a result of overuse of the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons, which pass through the first extensor compartment. It is characterized by an isolated, painful inflammation of the tenosynovium proximal to the tabatière (anatomical snuff-box) near the radial styloid process. The early stage is characterized by an unspecific swelling, later developing into a thickened extensor retinaculum, which narrows the tendon compartment and reduces the ability of the tendon to glide smoothly. Finkelstein’s test is positive (pain above the first extensor compartment during passive wrist ulnar deviation with a closed fist). Frequently tendinosis is also found ( Fig. 29.1 ). The clinical symptoms progress with the self-maintaining process.

Tenosynovitis of the second extensor compartment containing the tendons of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis muscles is rare ( Fig. 29.2 ). More frequently, however, is the intersection syndrome of the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB) and abductor pollicis longus (APL) muscles, which may be misinterpreted as tenosynovitis of the second tendon compartment. The intersection syndrome is a friction syndrome of the EPB and APL 4–8cm proximal to the wrist, where both muscles obliquely traverse and intersect with the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis tendons. This syndrome is common in individuals who row, lift weights, or paint.

In the third extensor compartment containing the extensor pollicis longus tendon, tenosynovitis develops relatively often after repetitive activities such as playing drums or secondary to wrist trauma such as distal radius fractures. The condition is rarely painful andmay lead to a spontaneous rupture of the tendon.

In the fourth extensor compartment consisting of the extensor indicis and extensor digitorum tendons, general tenosynovitis of all tendons ( Fig. 29.3 ) is less often observed than an extensor-indicis syndrome of the index finger. Since about 75% of the belly of the extensor indicis muscle lies within the fourth tendon compartment and numerous variants exist, this type of inflammation is somewhat more common.

Tenosynovitis of the tendon of the extensor digiti minimi muscle in the fifth extensor compartment is rare.

The sixth extensor compartment with the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) tendon is often affected. In this compartment, the extensor retinaculum contributes little to the stability of the tendon; instead, an osteofibrous tunnel formed by the ulnar styloid process, a bony groove in the ulna head, and an additional fibrous membrane maintain the position of the ECU tendon during wrist motion. This constellation predisposes to a tendinous ECU tunnel syndrome in the presence of tendinosis and tenosynovitis. With severe tenosynovitis, concomitant inflammatory reactions on the ulnar styloid process and the ulnocarpal complex can appear ( Fig. 29.4 ). If the osteofibrous unit is injured, repeated subluxations of the tendons are observed.

Tendinosis and Tenosynovitis of the Flexor Tendons

The flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) and flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendons are most often affected at the level of the wrist. Dependently of exertion, the flexor tendons of the fingers can be involved in groups or individually ( Figs. 29.5 , 29.6 ).

The FCU tendon is affected either as an insertional tendinosis near the pisiform and hamate and metacarpal V or as tenosynovitis at the level of the wrist ( Fig. 29.7 ). Common causes are repetitive flexion movements of the wrist, as in tennis.

The FCR tendon traverses in a separate osteofibrous compartment within the carpal tunnel before insertinginserting at the bases of the second and third metacarpals. It courses over the scaphoid tubercle and then passes through the sulcus of the trapezium. Therefore, distal scaphoid fractures and scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) osteoarthritis ( Fig. 29.8 ) play a causative role in tendinosis and tenosynovitis, as does primary overuse.

A special form of tendinosis and tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons is the trigger finger/thumb. This condition is characterized by blockage of a flexor tendon due to an absolute or relative stenosis of the tendon sheath. When this stenosis is overcome with increasedforce, the characteristic triggering of the affected finger occurs during flexion or extension. In an advanced stage of disease, the narrowing can no longer be overcome, and the affected finger remains fixed in a flexed or extended position. Pathogenetically, there is a stenosing tenosynovitis at the predisposed site at the level of the A1 anular ligament. The acquired form usually appears after the age of 50 years and is associated with a thickening of the tendon and/or its sheath. It is caused by degenerative changes or intermittent overuse. In the rarer congenital form in infants or small children, the thumb is usually affected. There is either no pain or pain only during the snapping movement. The diagnosis is made clinically. Imaging procedures are required only to clarify particular clinical objectives.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography

Osseous changes are generally not observed in tenosynovitis. Soft-tissue swelling and obliterated fat-stripes near the affected tendon can be reliably detected with digital luminescence radiography because of its increased resolution. In de Quervain disease, this sign is observed lateral of the radial styloid process.

Ultrasonography

The most reliable sonographic sign of tenosynovitis is evidence of fluid in the tendon sheath. This appears as an hypoechoic cover around the hyperechoic tendon ( Figs. 29.2 , 29.5 ). Synovial proliferation appears as a peritendinous hypoechoic structure. In de Quervain stenosing tenosynovitis, a hypoechoic zone around the tendon of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis muscles can be seen in the axial plane. The pathoanatomic substrate is swelling of the tendon sheath with edema.

Thickened tendons with normal echogenicity are found in the trigger finger in high-resolution ultrasonography. A mild, delineated thickening in the tendon proximal to the A1 anular ligament is found in approximately 50% of patients. In a third of the cases, small cystlike structures can be seen on the palmar surface of the tendons, whose pathoanatomical correlate has not been defined. These may correspond to the so-called anularligament cysts.

Computed Tomography

Reactive tenosynovitis can be recognized by means of a halolike, hypodense (15–30 HU) fluid collection around the affected tendon. Ultrasonography and MRI are superior to CT for identifying tenosynovitis. Therefore these procedures are usually performed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

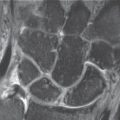

In MRI, acute tenosynovitis is also characterized by fluid accumulation in the tendon sheath. In T1-weighted images the fluid is hypointense, and in T2-weighted images it is hyperintense (Figs. 29.1a, 29.3 , 29.6a , 29.7 ), contrasting strongly with the normal low signal of tendons. The tendon sheath is usually only slightly to moderately thickened; its synovium can show different degrees of contrast enhancement after intravenous administration of gadolinium (Figs. 29.1b, 29.4 , 29.6b , 29.8b ). For differential diagnosis, in tenosynovitis the fluid surrounds the tendon uniformly, but in rupture of an anular ligament the increase in fluid is located focally between the tendon and the bone (Fig. 29.13a).

In chronic tenosynovitis, there is usually a more prominent thickening of the tendon sheath and little or no peritendinous fluid collection ( Figs. 29.1 , 29.4 , 29.6 ). Frequently, there is simultaneous tendinosis with thickening and/or signal increase of the tendon.

Hyperintense tendinosis must be differentiated from artificial signal increase due to the “magic-angle” phenomenon. On short-TE images (less than 22msec), this effect is demonstrated in tendon sections oriented at approximately 55° to the external magnetic field.

Therapeutic Options

Tenosynovitis generally requires rest of the affected muscles, preferably with immobilization of the forearm and hand, including the fingers, on a splint. More severe tenosynovitis may require the local or systemic administration of an anti-inflammatory agent. The chronic stenosing form of de Quervain tenosynovitis is mostly treated by surgical release of the first extensor compartment.

Tendon Rupture

Pathoanatomy and Clinical Symptoms

Complete tendon tears usually occur suddenly during extreme movement and are often associated with a preexisting traumatic lesion, chronic partial rupture, or myxoid degeneration of the tendon. The tear frequently occurs at the bony insertion and in combination with an avulsion fracture (Chapter 26). Partial tears may be caused by sudden exertion or by chronic, recurrent injuries. Torn tendons are accompanied by localized swelling of the soft tissues, as well as deformity and deficient extension or flexion.

Diagnostic Imaging

Radiography

Conventional radiographs of the affected finger can only confirm or exclude bony involvement of a ruptured tendon ( Figs. 26.5 , 26.6 ). An avulsed fragment may sometimes be located at a small distance from its origin because of distraction by the tendon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree