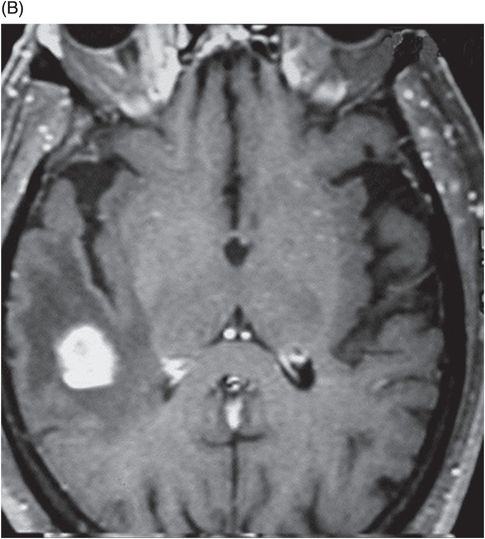

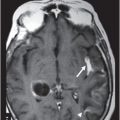

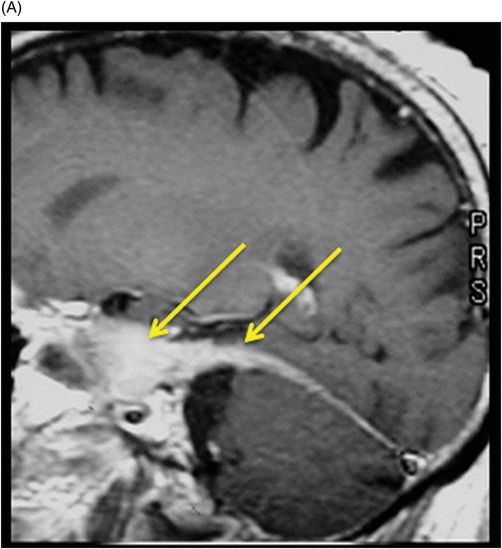

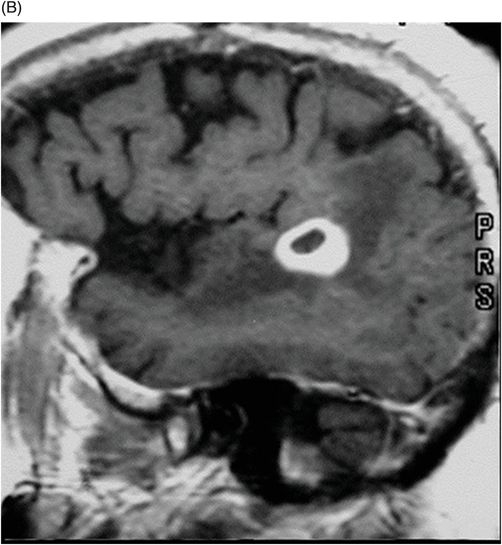

(A–B) Sagittal T1WI postgadolinium images through the level of the tentorium and the right temporal lobe.

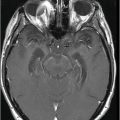

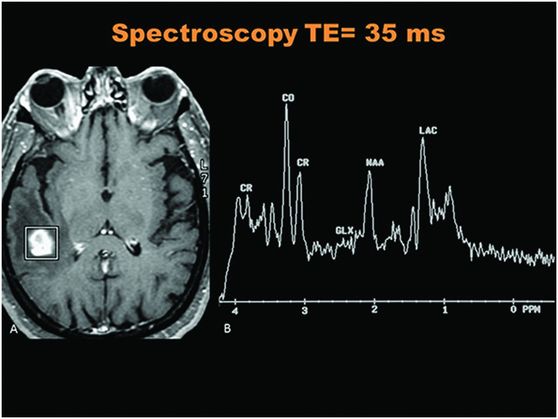

Spectroscopy through the level of the lesion in the right temporal lobe.

Syphilitic Gumma

Primary Diagnosis

Syphilitic gumma

Differential Diagnoses

Glioblastoma

Bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal abscesses

Toxoplasmosis

Lymphoma

Imaging Findings

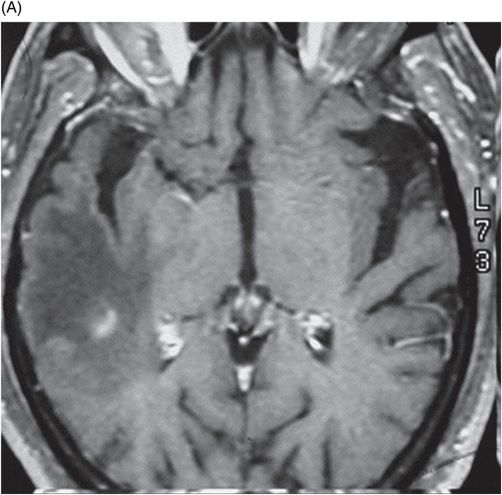

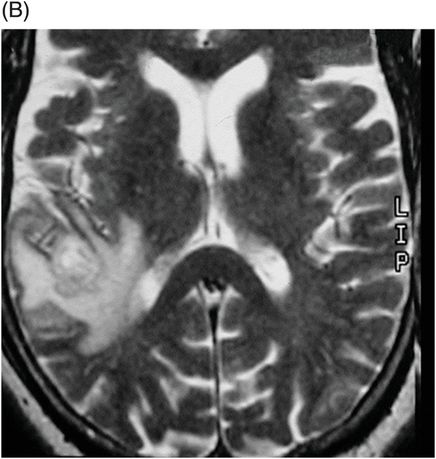

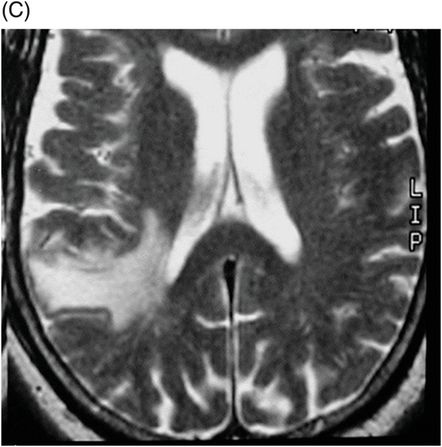

Fig. 41.1: (A–C) T2WI demonstrated a heterogeneous, hyperintense mass in the posterior part of the right temporal superior gyrus, surrounded by vasogenic edema. Fig. 41.2: (A–C) Axial T1WI postcontrast demonstrated a ring-enhancing lesion with mass effect in the periventricular white matter, adjacent to the atrium of the right ventricle. Fig. 41.3: (A) Sagittal T1WI postgadolinium image showed thickening and enhancement of the anterior portion of the pachymeninges in the right tentorium (arrows), (B) at the same side of the ring-enhancing lesion. Fig. 41.4: Spectroscopy of the lesion showed a high choline peak, low NAA peak, and high lipid and lactate peaks, similar to spectroscopy findings of a high-grade tumor.

Discussion

In general, glioblastoma is a more infiltrative lesion. Toxoplasmosis is a ring-enhancing lesion with an eccentric nodule. Pyogenic abscesses have a ring-enhancement appearance, with restricted diffusion in the central area of necrosis. Fungal lesions are hypointense on T2 images. Lymphoma shows restricted diffusion and solid areas of enhancement postgadolinium in non-HIV patients.

Although syphilitic gumma is a ring-enhancing lesion found in the brain, it should be differentially diagnosed to distinguish it from other brain masses. In the case of this patient, a brain tumor was first suspected, based on initial imaging. In our case, the presence of thickening and intense enhancement of the pachymeninges of the tentorium at the same side strongly suggested an infectious disease etiology. The associated clinical history, promiscuous behavior, and clinical findings including positive CSF laboratory findings for VDRL, and MR images demonstrating a ring-enhancing lesion with pachymeningeal involvement also supported an infectious etiology. Surgical biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of cerebral gumma due to neurosyphilis.

Syphilis, along with the recent increase of HIV patients, has also been on the rise. It has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, including cerebral gumma, a manifestation of neurosyphilis; however, it is rare and can be cured by penicillin. Thus, cerebral gumma needs to be differentially diagnosed from other brain masses that may be present in syphilis patients.

Syphilis is a chronic, systemic infectious disease caused by the spirochete, Treponema pallidum, and can affect most organs. It is commonly transmitted via sexual contact; however, it is vertically transmitted from mother to fetus in some cases. It was expected to be eradicated by the use of penicillin, one of the most effective antibiotics. Since the early 2000s, however, syphilis has been reported to be prevalent among HIV patients in several countries. Clinically, syphilis progresses through the following series of stages: incubation period following initial infection, primary syphilis, secondary syphilis, latent syphilis, and late syphilis (or tertiary syphilis). Late syphilis includes cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and late benign syphilis (gummatous syphilis). Recent studies showed that syphilis is prevalent in HIV-positive patients, is characterized by a broad spectrum of symptoms, and that it can occur after 1 to 25 years following infection. Various manifestations of neurosyphilis may be observed, such as asymptomatic, meningovascular, and parenchymal neurosyphilis. Of the various types of neurosyphilis, gummatous neurosyphilis is rare; its occurrence is not associated with HIV infection, and it is commonly misdiagnosed as a brain tumor. Brain gumma is a curable disease; therefore, an appropriate diagnosis is essential for optimal patient treatment and prognosis. The etiology of brain gumma due to neurosyphilis was presumed to be an excessive response of the cell-mediated immune system to T. pallidum.

Histopathologically, this case was characterized by the presence of a circumscribed mass resembling granuloma at the site where lymphocytes or plasma cells infiltrated the brain parenchyma or meninges. This granuloma underwent fibrotic or necrotic transformation over time.

Spirochetes are rarely identified from tissue samples. In the present case, the spirochetes were detected on histologic examination. Brain gumma commonly develops from the dura and pia mater over the cerebral convexity or at the base of the brain. Single or multiple masses attached to the dura mater can invade brain parenchyma. The symptoms of brain gumma are similar to those of other tumors arising from brain parenchyma and are often accompanied by seizures. The radiologic findings of brain gumma are very inconsistent. On CT scans, the lesion was localized at the periphery of brain tissue. The findings of non-contrast-enhancement CT revealed a hypodense area with no mass effect. On contrast-enhanced CT scans, however, brain gumma can be observed to be accompanied by severe edema of adjacent tissue. T1WI MR scans showed a low-intensity or isointensity mass. T2WI MR scans, however, revealed a homogeneous and high-intensity mass. The adjacent area of the mass showed high intensity on T2WI and a low intensity on T1WI.

Brain gumma occurs commonly in association with the meninges. Accordingly, the location of lesion and the findings of contrast-enhanced imaging are useful in making a presumptive diagnosis of brain gumma. In the present case, brain tumor was suspected, since the central portion of the lesion was necrotic. The MR spectroscopic image showed higher peaks formed by choline compounds, indicating the possibility of a tumor. The choline peaks in MR spectroscopy represent the complexes of phosphorylcholine and glycerophosphorylcholine found in the membrane, and these complexes play a role in cell membrane synthesis or destruction. Choline peaks are thus regarded as cancer markers. Low NAA peaks mark neuronal populations, and higher peaks of lipids and lactate (anaerobiosis) typically indicate high-grade brain tumors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree