43 Cystic Bone Lesions

Cystic bone lesions are usually round osteolytic destructions of the bone structure that appear either as a independent skeletal entity or as a particular symptom of a multitude of focal or systemic diseases of the hand skeleton. The diagnosis can usually be made synoptically together with the clinical and laboratory findings, the age of the patient, and radiographic symptoms of the focus (marginal sclerosis, permeation, localization) and its surroundings (concomitant signs of osteoarthritis, arthritis and tumorous destruction). Further morphological differentiation occasionally requires the use of skeletal scintigraphy, CT, or MRI.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Symptoms

Cystic lesions in the skeleton of the hand have in common only demarcated loss of the bone structure. Their pathogenesis is extremely wide. They can appear either as independent skeletal entity or as a hallmark of an underlying disease. Various concomitant reactions, such as marginal osteosclerosis, bone expansion, periosteal reaction, and enthesopathic changes, may help to asses the nature of the cystic lesions and to identify the underlying disease. The cysts themselves usually cause no complaints and only become symptomatic when secondary phenomena or complications occur, e.g., bone-marrow edema or a pathologic fracture. Otherwise, symptoms in skeletal sections with cysts are determined by the primary disease.

Classification

Table 43.1 provides an attempted summary of the heterogeneous group of cystic lesions on the skeleton of the hand: there are overlaps.

|

Bone Cysts with No Pathological Relevance

Vasa Nutricia

“Vascular holes” represent vascular canals in the orthograde projection.

Posttraumatic Hemorrhagic Cysts

There is a fine osteosclerotic margin around a focal osteolytic obliteration of the cancellous bone. The previous trauma often can no longer be recalled.

Necrobiotic Pseudocysts, Idiopathic Carpal Cysts

Local ischemic conditions are the pathogenesis of non-expanding osteolyses of up to 3 mm with thin osteosclerotic margins. During reparative processes there occurs circumscribed bone-marrow fibrosis or – as a result of metaplasia of the surrounding pluripotent osteoblasts – the formation of cysts, which are lined with synovium-like tissue.

Avascular Osteonecroses of the Carpus

Cystic inclusions can be found in the lunate in ischemic lunate osteonecrosis (see Figs. 30.3 , 30.7 ) and in both fragments in scaphoid nonunion (see Figs. 20.5 , 20.6 , 20.7 ). From stage II onward in both disease entities, there is formation of resorption cysts surrounded by a zone of osteosclerosis. These arise as a result of necrosis of the bone marrow and the cancellous bone in the form of cystic defects. The cysts are located in the subchondral area of the lunate. In the scaphoid, they lie along the pseud-arthrotic cleft in both scaphoid fragments. There is almost always a concomitant osteosclerosis of the cancellous bone.

Enthesopathic and Arthritic Diseases

Bone cysts that appear in enthesopathic diseases are usually subchondral or subcortical.

Subchondral cysts and intraosseous ganglion cysts cannot be differentiated histologically. Their walls consist of a cell layer resembling synovium, and the surrounding wall is osteosclerotic. Appropriate projections or slices display a direct neighborhood of the cystic cavity and the surface of the affected bone in both types of cysts, but the pathogenesis is fundamentally different:

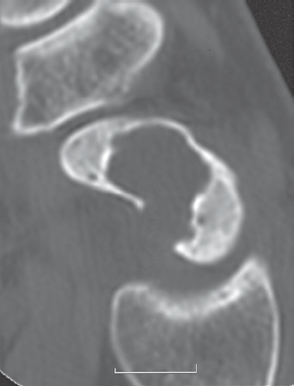

A ganglion cyst ( Figs. 43.3 – 43.6 ) is caused by mucoid degeneration of an inserting ligament with consecutive neogenesis of fibrovascular tissue. Its capillaries exude fluid from blood plasma. The fluid enters the surrounding bone space. This induces adjacent pluripotent bone cells to produce a synovium-like cell layer. The pathogenesis determines the intraosseous position of the cysts at the ligament insertions (Chapter 10). The articular cartilage always remains intact, and there are generally no signs of osteoarthritis. The cyst cannot be seen during arthroscopy despite being immediately adjacent to the bone surface along the thickened tissue structures of the affected ligament, even when the bone structures are extremely thin ( Fig. 43.3 ). Predisposed sites are the insertions of the scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments, the ulna head, and the capitate with it numerous ligamentary insertions. The density values of cysts in CT are between 10 and 30 HU.

Subchondral cysts ( Fig. 43.1 ) develop on the parts of joint surfaces that are exposed to a high mechanical load that abrades the articular cartilage. The cysts are in direct contact with the joint space and can be seen during arthroscopy. Contrary to earlier opinion, the cyst-surrounding synovial layer is not the articular synovium that has folded into the defect but has arisen secondarily as a desmoplastic transition of pluripotent bone cells caused by contact with joint fluid. Osseous reactions in the ulnocarpal impaction syndrome, as shown in Fig. 43.1 in addition to radiocarpal osteoarthritis, are similar. Radiographic signs of osteo-arthritis include narrowing of the joint space, sub-chondral osteosclerosis, and osteophytic formations.

Signal Cysts and Arthritic Erosions

One of the early signs of arthritic joint disease is the signal cyst, which has either no, or only thin, marginal osteosclerosis (Fig. 43.2a). At the beginning of the arthritic destruction process, erosions appear, initiallyin the bare areas where the articular bone is not covered by cartilage. They have no sclerotic margin and are accompanied by periarticular osteopenia and narrowing of the joint space. The other direct arthritic signs become manifest in the late stages. In the mutilation stage of rheumatoid arthritis, large cystic bone defects can develop adjacent to the affected joint (Fig. 43.2b).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree