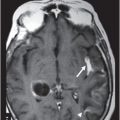

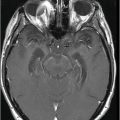

Axial T1WI at the level of thalamus.

Coronal gradient echo image at the level of thalamus.

Axial diffusion image at the level of centrum semiovale.

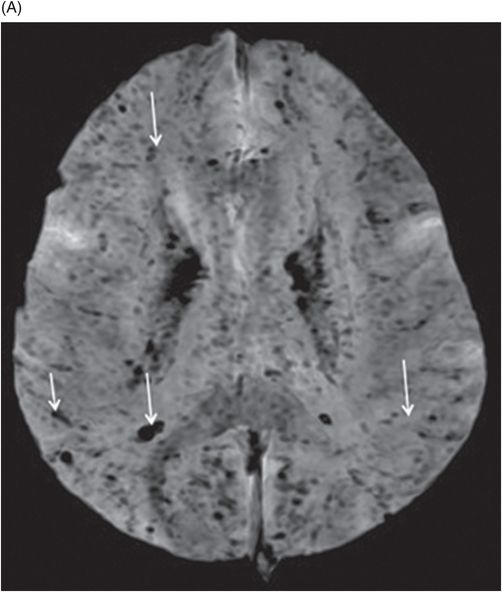

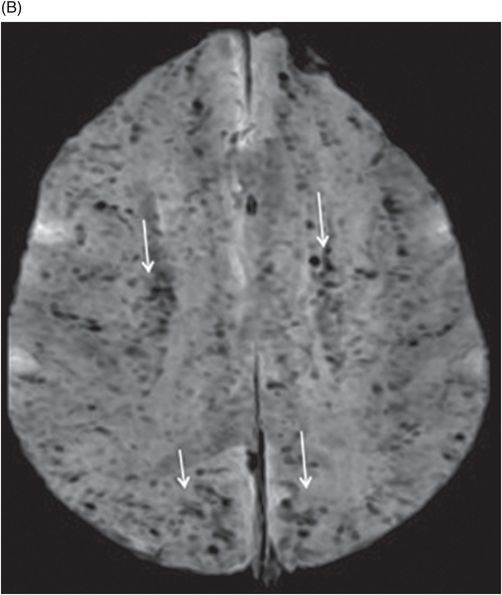

(A–B) Axial susceptibility-weighted images at the level of centrum semiovale and corona radiata.

Cerebral Malaria

Primary Diagnosis

Cerebral malaria

Differential Diagnoses

Hemorrhagic viral encephalitis

Hemorrhagic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

Toxicities, metabolic encephalopathies

Imaging Findings

Patient Case A: MRI shows hemorrhagic bithalamic lesions with hyperintense signal on Fig. 47.1: T1WI, Fig. 47.2: FLAIR, and Fig. 47.3: Blooming on coronal gradient echo image. Patient Case B: Fig. 47.4: Heterogeneous foci with diffusion restriction are noted in the deep white matter and subcortical regions (arrows). Fig. 47.5: (A–B) SWI images show multiple linear foci with significant blooming in the subcortical and central deep white matter (arrows), which correspond to capillary sludging and hemorrhage caused by parasitemia.

Discussion

The imaging findings of bithalamic lesions have a wide list of differential diagnoses comprising infective, metabolic, and neoplastic pathologies. The clinical history and high index of suspicion in an endemic zone with pertinent hematologic investigations helps in arriving at the diagnosis of cerebral malaria.

Hemorrhagic encephalitis, especially Japanese B encephalitis, can have similar imaging features and is one of the major differential diagnoses to be excluded in a patient residing in an endemic zone. Negative hematologic and CSF analyses play a key role in the differential diagnosis. Hemorrhagic ADEM can also have the same imaging manifestations; however, the history of endemic zone as in Case A and travel to an endemic zone and clinical presentation with splenomegaly help in exclusion.

Malaria is a widespread, endemic disease in most South Asian, African, and South American countries. Cerebral malaria is caused by Plasmodium falciparum and transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito. Patients typically present with high-grade fever, altered level of consciousness, seizures, and generalized constitutional symptoms that fluctuate with the blood parasitemia. The neurologic symptoms are often non-specific because of diffuse brain involvement. The imaging manifestations develop because of cytokine-induced damage and mechanical capillary blockade instigated by parasite-infested erythrocytes. Cytokine release leads to increased cerebral volume due to vasodilatation, decreased cerebral perfusion, and hypoglycemia. Imaging findings correlate well with histopathology, which demonstrates sequestration of infected erythrocytes in the smaller perforating blood vessels and capillaries with white matter necrosis.

A wide spectrum of neuroimaging findings have been described on T2, FLAIR, DWI, GRE, and SWI sequences involving the cortical and subcortical white matter, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, thalamus, and the cerebellum due to vasogenic and cytotoxic edema, haemorrhage, and infarcts. The imaging spectrum has been broadly classified as normal brain appearance on CT and MRI, diffuse cerebral edema, bilateral thalamic changes with diffuse cerebral edema, and/or bilateral thalamic and cerebellar involvement with diffuse cerebral edema. The sludging of capillaries by infested erythrocytes can be appreciated on GRE and SWI that are highly sensitive for hemorrhage and sluggish blood flow. Imaging features similar to central pontine myelinolysis and cerebellar syndrome with demyelination have been reported. A high index of clinical suspicion is required in endemic zones as the imaging findings can be similar to viral encephalitis or hemorrhagic ADEM. Although cerebral malaria constitutes only 2% of malarial cases; it can be life-threatening, especially in the pediatric age group. Mortality ranging from 20% to 50% has been reported – even with effective antimalarial therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree