Axial T2WI at the level of the basal ganglia.

T2* GRE.

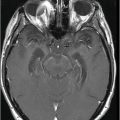

Axial postgadolinium T1WI.

Acute Necrotizing Encephalopathy

Primary Diagnosis

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy

Differential Diagnoses

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)

Leigh syndrome

Reye syndrome

Cerebral venous thrombosis

Occlusion of the Percheron artery

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy and lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS)

Myoclonus epilepsy and ragged red fibers (MERRF)

Imaging Findings

Fig. 58.1: Axial T2WI at the level of the basal ganglia showed bilateral, symmetric hyperintense lesions involving both basal ganglia that are associated with mild edema and mass effect. Fig. 58.2: Coronal T2WI showed bilateral insular subcortical white matter involvement. Additional lesions are seen in the brainstem and cerebellar middle peduncles. Fig. 58.3: T2* GRE imaging showed petechial hemorrhagic foci in the right thalamus and in the subcortical white matter of both insular cortexes. Fig. 58.4: Axial DWI showed no abnormal DWI restricted diffusion in the brain parenchyma. Fig. 58.5: Axial T1WI postgadolinium administration showed bilateral symmetric ring-enhancing lesions in both basal ganglia.

Discussion

The previously mentioned list of differential diagnoses shares similar imaging findings and differentiation among them can be made by assessing clinical presentation, age of involvement, history, and laboratory findings. Reye syndrome is characterized by an acute non-inflammatory encephalopathy and fatty degenerative liver disease, associated with gastroenteritis or viral infection. Patients usually present with increased liver transaminase levels, hypoglycemia, and hyperammonemia, data that can be helpful in determining the correct diagnosis. Leigh syndrome is a genetic mitochondrial disorder characterized by progressive neurodegeneration, psychomotor delay, and hypotonia, which does not cause acute encephalopathy.

MELAS, another mitochondrial disease, is characterized by acute onset of headache, hemianopia, seizures, psychosis, aphasia or other focal symptoms, with muscle weakness and sensorineural hearing loss. Patients can evolve to cognitive deficit and dementia in chronic stages (see Part V: Case 74).

Myoclonus epilepsy and ragged red fibers (MERRF) is a progressive multisystem syndrome, which usually begins in childhood, but can also occur in adulthood. Patients usually present with myoclonus, seizures, ataxia, hearing loss, lactic acidosis, short stature, exercise intolerance, dementia, cardiac deficits, eye abnormalities, speech impairment, and a characteristic microscopic abnormality observed in muscle biopsy, the ragged red fibers.

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is usually a monophasic demyelinating disease, affecting the gray and the white matter of the brain and spinal cord. It has a temporal relationship to prior infections or vaccination history. Patients can present with widespread CNS dysfunction, fever, and headache, seizures, and consciousness impairment. On MRI, lesions are poorly marginated, predominantly in the subcortical/deep white matter. Inflammatory lesions can also be seen in the spinal cord. Laboratory evaluation of CSF may reveal mild pleocytosis, uncommon IgG production, and oligoclonal bands.

Occlusion of the Percheron artery and cerebral venous thrombosis usually occur in adulthood, with an acute onset of headache and variable degrees of loss of consciousness, depending upon which thalamic nuclei were involved. Executive functions, language, motor skills, and spatial cognition may also be affected. Diffusion-weighted imaging is important in depicting cytotoxic edema due to ischemic changes. Susceptibility-weighted images can show the blooming artifacts arising from the occluded veins and dural sinuses.

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), also known as acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood, is a recently described disease by Mizuguchi et al., in 1995. The disease is a distinct form of acute encephalopathy triggered by viral infections such as human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6), parainfluenza, influenza A and B, H1N1, swine flu, herpes simplex virus, rotavirus, measles virus, Coxsackie A9, Epstein-Barr virus, and sometimes mycoplasma.

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy has a worldwide distribution, but is more common in Asian countries. This encephalopathy usually occurs among children aged 5 months to 10 years, normally beginning around 4 years of age, with no gender predilection. It is commonly precipitated after a febrile respiratory illness, followed by the onset of acute encephalopathy. Additional symptoms may include recurrent vomiting, seizures, altered mental status which rapidly progresses to coma, and variable degrees of hepatic dysfunction.

The most common biochemical abnormalities described in ANE patients are metabolic acidosis, thrombocytopenia, high blood serum levels of aspartate aminotransferases, creatine kinase, liver transaminases, and increased levels of blood urea nitrogen, as well as increased CSF proteins.

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy can be sporadic or recurrent familial, which is related to a dominant trait in the gene (2q13) encoding the nuclear core protein RAN binding protein 2.

Genes on other loci are also involved in recurrent familial. Located on chromosome 2 (2q12.1-2q13), ANE shows incomplete penetrance (estimated about 40%). These patients tend to have recurrent ANE with more severe neurologic sequelae.

Imaging features of ANE are characterized by multiple, symmetric lesions showing increased T2 signal in the thalami, frequently with accompanying lesions in the brainstem tegmentum, periventricular white matter, internal capsule, putamen, and cerebellum. The most distinctive neuroimaging finding of ANE is symmetric, multifocal lesions that invariably involve the thalami.

On CT, ANE lesions show low density on CT and T1/T2 prolongation on MRI studies. After contrast administration, ring enhancement typically develops around the hemorrhagic areas by the second week of illness. Hemorrhage has been known to occur predominantly in the central portion of the involved deep gray matter, but not in the cerebral white matter. Intracranial hemorrhage and cavitation may also be seen, both of which are associated with a worse prognosis.

Diagnostic confirmation is based on clinical symptoms and signs of acute encephalopathy, in the presence of characteristic imaging patterns. Polymerase chain reaction can be positive for some of the viruses responsible for initiating ANE, and can help determine the correct diagnosis. Hepatic dysfunction is another hallmark of the disease. The main differential diagnosis includes Reye syndrome, MELAS, MERRF, and Leigh syndrome.

Histologic examination can demonstrate bilateral hemorrhagic necrosis in thalami, caudate nuclei, and cortical or subcortical areas. The tegmentum and pontine nuclei, the cerebellar cortex, and the dentate nucleus can be similarly involved. The capillary network can be prominent, with small, perivascular hemorrhages; occasionally confluent cytolysis of the neurons and glial cells, lipid-laden perivascular macrophages, myelin pallor, and spongiform changes can be seen in the affected areas.

The prognosis and outcome can be poor in patients who do not start early treatment with steroids. Treatment is usually supportive and the use of steroids can be helpful. Patients with brainstem lesions usually have poor outcome. Magnetic resonance imaging signs of poor prognosis are cavitated parenchymal lesions with hemorrhage. It is not clear yet whether the use of gamma globulin can improve the outcome. As complications, patients can develop weakness, spasticity on extremities, memory disturbance, and difficulties in speech, intellectual impairments, and epilepsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree