Midsagittal T1WI showing the corpus callosum.

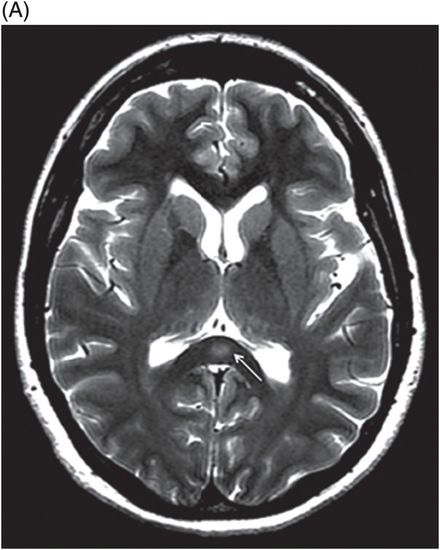

(A) Axial T2WI and (B) FLAIR images at the level of lateral ventricles and splenium of corpus callosum.

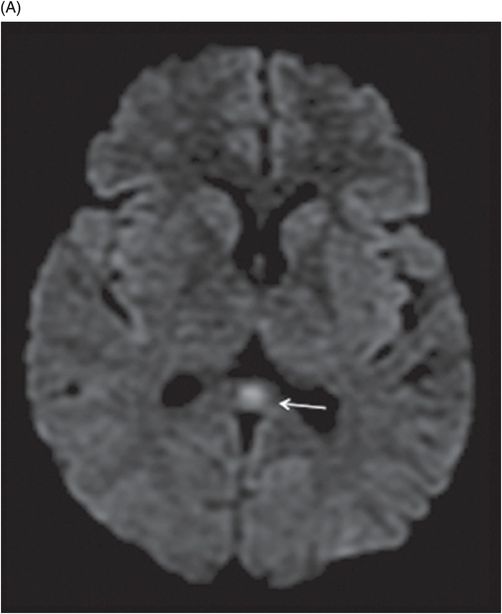

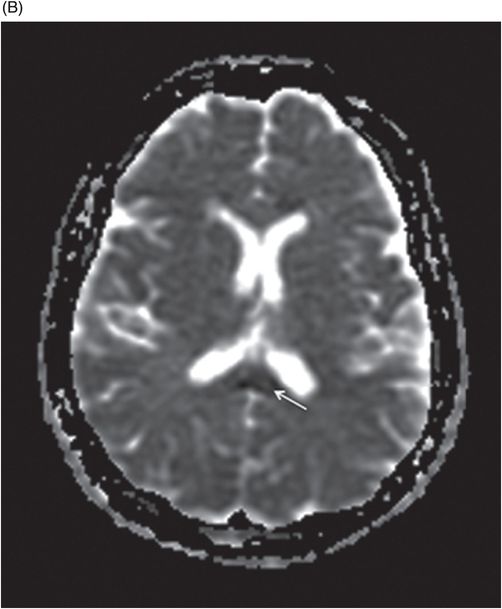

(A) Axial diffusion and (B) ADC images at the level of lateral ventricles and splenium of corpus callosum.

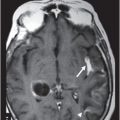

Axial T2W image at the level of lateral ventricles and splenium of corpus callosum.

Transient Splenial Lesion

Primary Diagnosis

Transient splenial lesion

Differential Diagnoses

Influenza-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy

Infectious diseases: influenza, rotavirus, herpes, measles, mumps, varicella, and cerebral malaria

Hypoglycemia, hypernatremia

Demyelinating diseases: diffuse axonal injury and Marchiafava-Bignami disease

Drug toxicities: cisplatinum, 5-fluorouracil, carboplatin, olanzapine, citalopram, and metronidazole

Methylbromide poisoning

Adrenoleukodystrophy

High altitude cerebral edema

Imaging Findings

Fig. 73.1: Sagittal T1WI showed a well-defined, hypointense, focal lesion in the splenium of corpus callosum (arrow). Fig. 73.2: (A) T2WI and (B) FLAIR images showed presence of a hyperintense lesion (arrows). Fig. 73.3: (A) Axial DWI showed diffusion restriction and (B) ADC showed low ADC values (arrows). Fig. 73.4: Axial T2WI shows complete resolution of the splenial lesion (6-week follow-up). Fig. 73.5: Axial DWI image also shows resolution of the lesion.

Discussion

In the given context of antiepileptic drug (AED) withdrawal as noted in the patient’s history, the identification of a focal splenial lesion with reversible signal changes on follow-up MRI scan that correlate with improved clinical condition of the patient confirm a diagnosis of antiepileptic drug withdrawal–reversible/transient splenial lesion.

Reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES) or transient splenial lesion is an entity that has been extensively illustrated in the recent neuroradiology literature. Of the several etiologies described in the wide list of differential diagnoses, a few conditions merit special consideration, especially AED withdrawal, infectious disease, or metabolic conditions. The other entities mentioned in the list of differential diagnoses can have similar imaging features but are out of context, based on the presenting history. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis excludes most of the infectious and inflammatory conditions. Metabolic and other drug-induced conditions, and the toxic conditions are excluded by hematologic evaluation.

Several causal mechanisms for RESLES have been proposed based on its etiology. They vary from excitotoxic intramyelinic edema, due to extracellular glutamate by increased neuronal activity, to cytotoxic edema, due to energy failure. In cases of viral infections, a toxin-mediated immune response or cytokine-induced axonal damage has been hypothesized. A few authors have also speculated that arginine-vasopressin or rapid correction of hyponatremia caused by AED withdrawal may play a role in RESLES. The corpus callosum consists of several distinct interhemispheric fibers with an increased splenic density; however, the resulting impact of RESLES on the corpus callosum is unclear. However, some studies attribute the probable cause to a lack of adrenergic tone, which makes the corpus callosum vulnerable to hypoxic vasodilatation and autoregulation failure (leading to overperfusion). Increased frequency of seizure activity or the type of epilepsy (partial versus generalized) has no relevance or correlation with the development of the splenial lesion. Use of approximately 14 AED drugs are associated with RESLES, including those most commonly prescribed (carbamazepine, phenytoin, and lamotrigine). Patients often present with encephalopathy or non-specific symptoms.

Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a non-enhancing round- to ovoid-shaped T2-FLAIR hyperintense lesion with diffusion restriction and low ADC values. On imaging, the lesion has been identified as early as 24 hours to 1 week after AED withdrawal. The overall incidence of reversible splenial lesion has not been reported; however, it occurs in 0.7% of patients undergoing presurgical evaluation that require AED withdrawal to provoke seizures and assess ictal EEG discharges. The signal changes usually resolve in a few months with complete reversal on follow-up MR imaging. The diversity of etiologies and multifactorial hypothesis make this condition a clinicoradiologic entity. If a history of AED withdrawal is absent, imaging features must be interpreted in the relevant clinical context and laboratory correlations to narrow down the possible list of differential diagnoses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree