A Surgeon’s Perspective on the Role of Interventional Radiology in the Management of Portal Hypertension

Liver transplantation is the only definitive therapy for patients with end-stage liver disease and portal hypertension. Enthusiasm for this potentially life-saving procedure must be tempered by recognition of a 1-year mortality rate of 10 to 20%, the adverse effects of life-long immunosuppression, and the need to have a compliant patient. Moreover, the inadequate supply of suitable organs precludes offering liver transplantation to all patients who might benefit from total liver replacement. On the other hand, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a percutaneous technique that effectively and reliably decreases portal venous pressure. TIPS is less invasive than transplantation or surgical portosystemic shunting procedures, can be performed expeditiously, and has a low 30-day mortality (3–15%).1–6

Despite these advantages, negative aspects of TIPS include a low primary patency rate and the development or exacerbation of encephalopathy in some patients. The primary patency rate is between 25 and 66%.7–9 Shunt occlusions often occur as a result of stenosis, usually at the level of the hepatic vein insertion site and occasionally within the liver parenchyma.10 Such stenotic areas can be dilated by balloon angioplasty, with additional stents inserted at the narrowed area. With revision, the 1-year patency rate is 85%. The encephalopathy following TIPS often is mild and usually can be treated medically. With refractory encephalopathy, either intentional shunt narrowing or temporary (8–12 hours) balloon occlusion of the shunt is effective.11,12

By providing portal venous decompression intraoperatively, TIPS can facilitate liver transplantation in patients considered to be good risks.13 This advantage may be overcome by intraoperative venovenous bypass, which is performed regularly at many institutions. Moreover, it should be recognized that TIPS placement can complicate the operative course of liver transplantation. After comparing 23 liver transplant patients who had undergone previous TIPS to 112 who had not, the group at the University of California, Los Angeles, noted that about 25% of the patients with a previous TIPS had intraoperative complications as a direct consequence of TIPS.14 Stent malposition with extension into either the suprahepatic inferior vena cava or the extrahepatic portal vein and stent perforation of the intrahepatic biliary tree leading to peritonitis were the primary causes of complications.

In addition, stent migration or extension, after multiple TIPS revisions, into the extrahepatic portal vein can promote portal vein thrombosis, which, if propagated into the superior mesenteric vein, may make liver transplantation technically unfeasible. Alternatively, location of the stent in the main portal vein may complicate dissection and control of this high-flow vessel and may lead to life-threatening hemorrhage because the surgeon then is forced to expose the portal vein beyond the stent and along its retropancreatic position. A stent extending into the suprahepatic vena cava can necessitate the use of wire cutters to transect the vein, leaving metallic spurs embedded in the vena cava. In one of our patients who had undergone multiple TIPS revisions, extension of the TIPS stent into the suprahepatic vena cava resulted in severe anastomotic stricture because of the presence of metallic remnants extending into the right atrium. Refractory ascites developed secondary to hepatic outflow obstruction, and the patient had to be relisted for transplantation despite having excellent hepatic parenchymal function. A second liver transplant in this patient could require any or all of the following: (1) interposition graft for the suprahepatic vena caval anastomosis, (2) median sternotomy for direct anastomosis to the right atrium, and (3) cardiopulmonary bypass.

Therefore, TIPS should not be considered a panacea for portal hypertension and should not be placed “cavalierly” as a bridge to transplantation in all patients. Any TIPS revision in a prospective liver transplant patient requires continuous dialogue between the interventional radiologist and the transplant surgeon. We argue strongly that TIPS placement in potential liver transplant candidates should be performed only by interventional radiology teams who recognize fully the ramifications of this procedure at the time of subsequent liver transplantation.

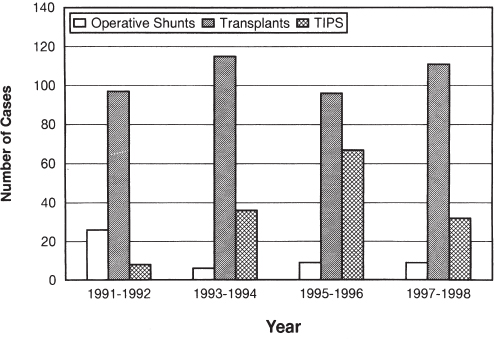

With the introduction of TIPS and liver transplantation, the number of surgically placed portosystemic shunts has diminished dramatically over the past decade. For example, at the University of Pittsburgh, over a 10-year period, only 10 portosystemic shunts were performed, whereas more than 2000 liver transplants were done.15 At the Cleveland Clinic, TIPS became the total shunt of choice. Consequently, between 1990 and 1994, only four total portosystemic shunts and 33 selective portosystemic shunts were performed surgically.16 The number of operative portosystemic shunts performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital during the era of liver transplantation and TIPS is summarized in Figure 9–1. The variability in the number of operative shunts performed among tertiary care centers is related to differences in expected waiting times to liver transplantation as well as individual practice preferences.

Figure 9–1 also illustrates other trends in the management of portal hypertension. The number of liver transplants has been relatively stable, primarily because of the static nature of the donor organ pool. After an increase in the number of TIPS in the mid-1990s, the fervor for this procedure was tempered by the reservations already mentioned and by the realization that this procedure has relatively high mortality rate (i.e., about 30%) in poorly compensated (Child-Pugh class C) patients. Finally, although the number of surgically placed portosystemic shunts has decreased, a steady stream of such operations are performed in major referral centers. Therefore, surgeons need to remain familiar with the various shunt procedures. Certainly, within institutions that care for patients with portal hypertension, expertise in shunt operations still is essential.17–19

FIGURE 9–1. Bar chart demonstrating the number of operative portosystemic shunt, liver transplants, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from 1991 to 1998.

Portosytemic shunts can be classified as total (nonselective) or partial (selective). Total shunts completely divert portal blood flow from the liver and thereby decompress the entire portal venous circulation. Because these shunts provide a lower resistance pathway than through the cirrhotic liver, splanchnic blood flow effectively is diverted away from the liver (hepatofugal portal blood flow). Such decompression generally is effective in managing patients with ascites and intractable variceal bleeding. Total shunts have excellent patency rates and can be performed expeditiously in emergent situations. On the other hand, in some cases, hepatofugal blood flow also accelerates liver failure and may lead to encephalopathy.

Portocaval, mesocaval, and central splenorenal (Linton) shunts are all examples of total portosystemic shunts. The mesocaval shunt is advocated in: (1) the emergent situation, (2) a prospective liver transplant patient because this shunt avoids dissection of the porta hepatis, and (3) patients with the Budd-Chiari syndrome, in whom an enlarged caudate lobe may preclude construction of a portocaval shunt for technical reasons.

A selective shunt, such as the Warren or distal splenorenal shunt (DSRS), attempts to disconnect the superior mesenteric and gastrosplenic components of the splanchnic venous system by anastomosing the distal end of the splenic vein to the left renal vein and ligating the coronary and gastroepiploic veins. In this manner, portal venous flow to the liver is preserved while the gastrosplenic circulation is decompressed.20,21 As a result, encephalopathy occurs less frequently, but ascites may be aggravated. The operation requires careful dissection of the splenic vein, with division and ligation of multiple veins draining the body and tail of the pancreas. These shunts have a higher rate of thrombosis, especially if the splenic vein caliber is not adequate (i.e., less than 1 cm). Also, in half of these patients, within 1 year, recollateralization between the superior mesenteric and gastrosplenic venous compartments results in loss of hepatopedal portal blood flow.22 Finally, subsequent transplantation may result in difficult dissection in approaching the celiac axis and damage to the splenorenal venous anastomosis, resulting in splenectomy.

Even if the dissection proceeds smoothly, some surgeons have suggested that splenectomy should be performed in most liver transplant recipients with a previous DSRS to provide adequate splanchnic blood flow to the hepatic allograft.23 When a previous splenectomy has been done or a small-caliber splenic vein is present, this shunt should not be considered.

Another form of partial shunt can be created by using a small-diameter graft (10 mm) to create a portacaval shunt. The coronary vein and other collaterals are ligated during this procedure, which originally was described by Sarfeh and Rypins in 1994.24 It has been advocated for alcoholic cirrhotic patients who are not candidates for liver transplantation because hepatopedal portal blood flow is difficult to maintain following a Warren shunt in this group of patients.25 Although a decreased incidence of encephalopathy has been noted in alcoholic cirrhotic patients who have undergone a small-caliber portocaval shunt, this operation needs further evaluation and longer follow-up. Moreover, some investigators have challenged the assertion by Sarfeh and Rypins that portal perfusion of the liver is preserved by using this technique.26–28

Esophagogastric devascularization is a nonshunting operative procedure for portal hypertension. It was developed by Suguira and Futagawa in Japan, where at that time shistosomiasis rather than alcoholic cirrhosis was the primary cause of portal hypertension.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree