- The patient with acute abdominal pain requires rapid assessment to exclude life threatening pathology (e.g. ruptured aortic aneurysm)

- The AXR is quick and easy to obtain, but is difficult to interpret and provides limited information

- CT (rarely US) is required in patients with acute abdominal pain

The patient presenting with abdominal pain may be suffering from a wide variety of conditions ranging from common, benign self-limited pathologies such as gastroenteritis to life-threatening emergencies such as a ruptured aortic aneurysm. It is vital to be able to differentiate these conditions using the most appropriate imaging modality (Box 13.1). These include the plain abdominal radiograph (AXR), ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not currently have a role in the initial management of abdominal emergencies. There are only a few common causes of acute abdominal pain and these will be highlighted in this chapter. AXRs are difficult to interpret and often non-diagnostic and therefore in these patients, CT (or sometimes US) should be performed initially.

- Suspected bowel obstruction

- Suspected perforation

- Renal colic

- Foreign body ingestion

Anatomy

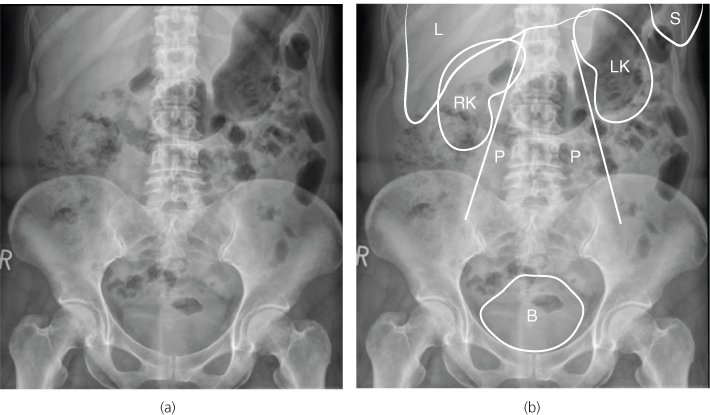

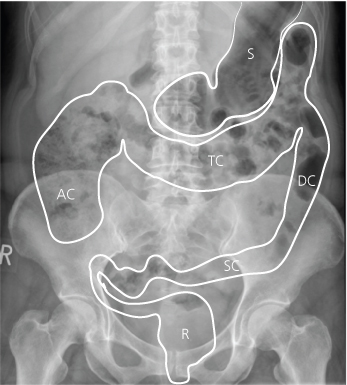

Normal appearances of the AXR vary (Figures 13.1 and 13.2), but Tables 13.1 and 13.2 show some useful general points to remember when assessing the radiographs.

Figure 13.1 (a),(b) Anteroposterior abdominal radiograph illustrating the position of the organs: L, liver; S, spleen; RK, right kidney; LK, left kidney; P, psoas; B, bladder.

Table 13.1 Positions of organs.

| Organ | Position | Appearance on radiograph |

| Liver | RUQ | Subhepatic edge visible |

| Spleen | LUQ | Rarely seen below twelfth rib |

| Kidneys | Flanks | Outlined by fat and psoas (L1–4), left kidney higher. |

| Pancreas | Central | Not visible and retroperitoneal |

| Bladder | Pelvis | May be visible if full |

Table 13.2 Position of bowel.

| Organ | Position | Appearance on radiograph |

| Stomach | Upper | Lies transverse across upper left and central abdomen |

| Small bowel | Central | <3 cm and contains air |

| Large Bowel | Peripheral | Contains air and faeces |

The solid organs are outlined by fat planes and can therefore be identified on the AXR. The bowel normally contains a variable amount of gas and the different segments of bowel can usually be differentiated by their site and morphology. Any gas seen outside the bowel is abnormal and is highly suggestive of perforation. The AXR is difficult to interpret and gives limited information and further investigations such as US or CT are often needed. In patients with severe abdominal pain, CT (or sometimes US) is advised as the first line of investigation.

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy—must include the pubic symphysis

- Air—exclude free intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal air

- Bowel—check gas pattern, size, and distribution. Exclude small bowel (SB) and large bowel (LB) obstruction

- Calcifications—check renal tract, vascular and other structures

- Densities—look for tablets and foreign bodies

- Edges—check hernial orifices and lung bases

- Fat planes—check psoas, properitoneal and perivesical fat planes

- Solid organs—look for liver, spleen and kidneys

- Skeleton—look at the bones for fractures

Adequacy

The standard AXR (Figure 13.1) is an anteroposterior view taken with the patient supine, not rotated and should include the pubic symphysis and show the hernial orifices and the properitoneal fat planes. These fat planes are thin layers of fat between the parietal peritoneum and the lateral wall muscles. An additional view of the upper abdomen may be necessary in tall patients.

Figure 13.2 Abdominal radiograph showing the position of the bowel. S, stomach; AC, ascending colon; TC, transverse colon; DC, descending colon; SC, sigmoid colon; R, rectum.

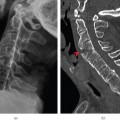

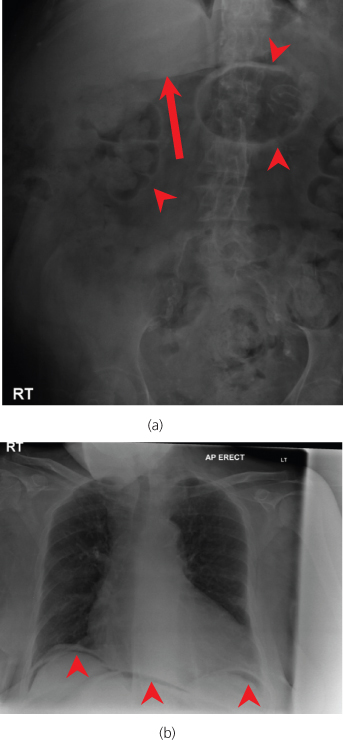

Figure 13.3 Abdominal radiograph and erect chest radiograph showing free gas (arrows) in a patient with perforated diverticulitis.

If a perforation is suspected an erect CXR should be performed (Figure 13.3). Small amounts of free air can be seen under the hemidiaphragm on the CXR, if enough time (at least 10 minutes) is allowed for the free air to rise. However, if perforation is suspected, a CT scan is indicated, as it is more sensitive at detecting free air and the underlying cause. The erect CXR may sometimes show chest pathology simulating an acute abdomen, such as pneumonia or aortic dissection.

Air

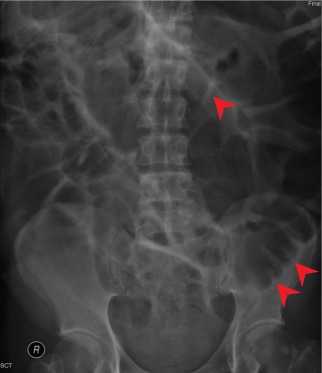

Free intraperitoneal air rises to the front of the abdomen on a supine AXR (Figure 13.3). This free air can be very subtle and hard to detect, so an erect chest radiograph is mandatory if perforation is suspected. Look for extraluminal air (Figure 13.4)—any gas outside the bowel wall is abnormal.

Figure 13.4 Abdominal radiograph showing free gas (arrows) in a patient with a postoperative perforation.

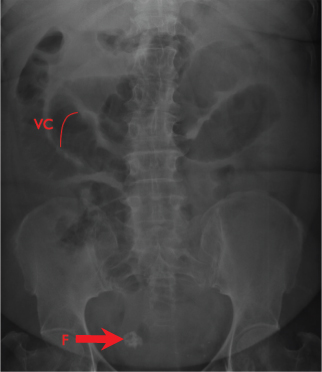

Figure 13.5 Abdominal radiograph in a patient with small bowel obstruction. Note the valvulae conniventes (VC) extend all the way across the bowel. A calcified fibroid (F) is noted in the pelvis.

Bowel

When the patient is supine, bowel gas rises to the parts of the gastrointestinal tract that are most anterior, in particular the stomach, transverse colon and sigmoid colon. The stomach is located above the transverse colon. The SB can be differentiated from the LB by the following features:

- Position: the SB lies in the central abdomen; the LB lies peripherally.

- Size: the SB should measure no more than 3 cm in diameter and is smaller than the LB. The large bowel has no definite measurement, but if the caecum dilates to more than 9 cm diameter in the presence of a suspected bowel obstruction, it infers impending perforation. In the presence of colitis, any part of the LB that measures more than 5.5 cm in diameter indicates a megacolon, but normal colon can easily be larger than this.

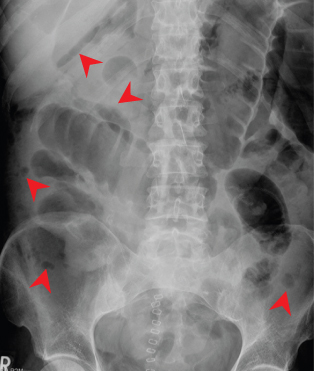

- Pattern: the SB has characteristic thin folds (Figure 13.5) (valvulae conniventes), which are close together and run across the whole bowel. The LB has thicker folds (Figure 13.6) (haustra) that do not run across the whole dilated LB. The distal ileum and sigmoid colon are relatively featureless and contain no folds.

- Content: the SB contains fluid and air, whereas the colon contains faeces, which have a characteristic mottled or solid appearance.

Figure 13.6 Abdominal radiograph showing large bowel obstruction in a patient with sigmoid cancer. Note the haustra (arrowhead) extend part of the way across the bowel.

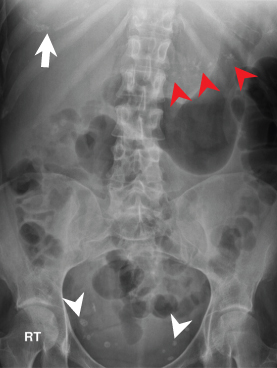

Figure 13.7 Abdominal radiograph showing pancreatic calcification (red arrowhead), phleboliths (white arrowhead) and costal cartilage calcification (white arrow).

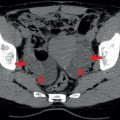

Calcification

Normal calcifications:

- Costal cartilage (Figure 13.7) can sometimes be seen in the upper abdomen as an incidental finding

- Phleboliths (Figure 13.7) are small calcified veins in the pelvis. They can be confused with ureteric stones

- Coarse, nodular calcification in mesenteric lymph nodes is an incidental finding lying between the left L2 transverse process and the lower right sacroiliac joint

- Vascular calcification is often seen in the aorta

Abnormal calcifications:

- Around 45% of renal (Figure 13.8) and ureteric calculi are visible on an AXR

- Abnormal vascular curvilinear calcification may outline aneurysms or thrombosed veins

- Only 10–15% of gallstones (Figure 13.8) are radio-opaque. Rarely, the gallbladder wall can calcify (porcelain gallbladder)

- Punctate fine stippled nodular calcification in the pancreas indicates chronic pancreatitis (Figure 13.7)

- Calcification in the spleen is usually caused by previous trauma or granulomatous or parasitic infections

- Appendicoliths and faecoliths may occasionally be seen

- Tuberculosis and schistosomiasis infections can cause calcification of the bladder wall

- Teeth can sometimes be seen in benign teratomas of the ovary (dermoid cysts) (Figure 13.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree