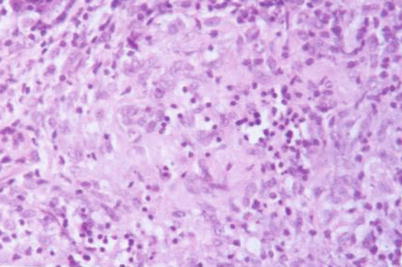

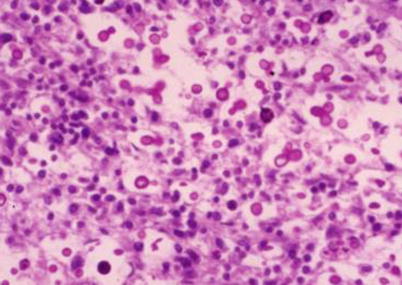

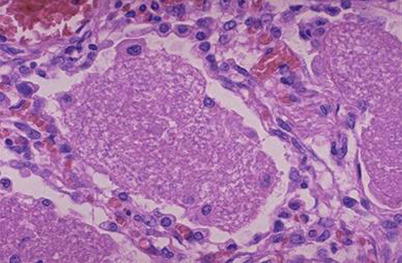

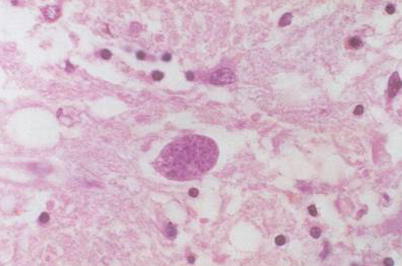

Fig. 5.1

Viral inclusions at the lung induced by CMV infection. H&E × 200

Bacterial Infections

The incidence rate of bacterial infection in patients with AIDS is 13–40 %. The most common pathogens are mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) and mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) that spread via the respiratory tract.

1.

AIDS complicated by MTB infection is commonly demonstrated with atypical pathological changes of tuberculosis (Figs. 5.2 and 5.3).

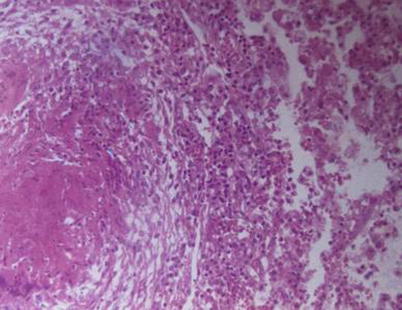

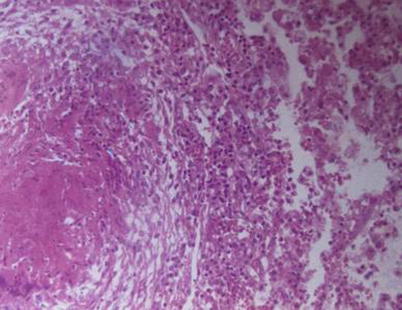

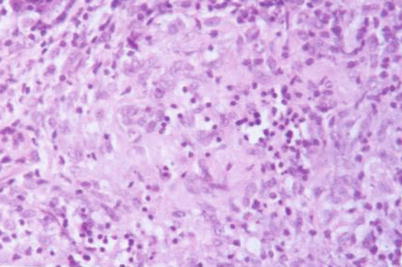

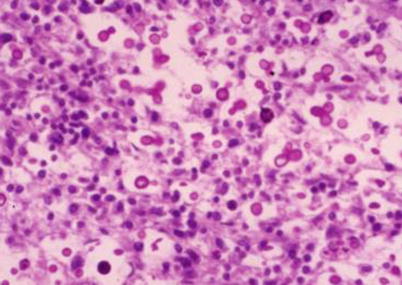

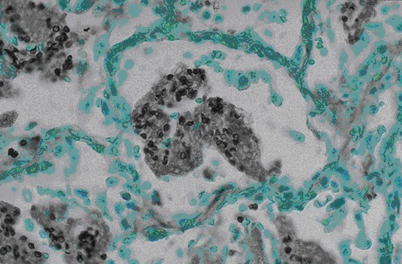

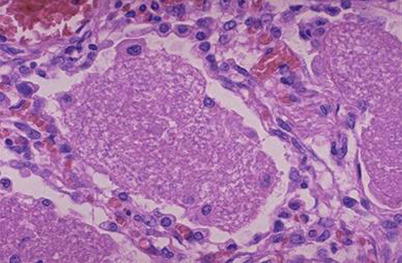

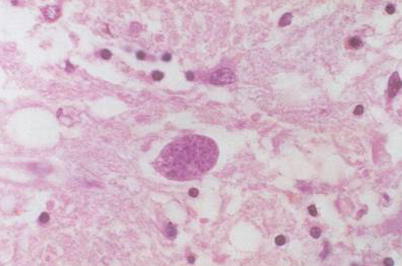

Fig. 5.2

Pulmonary TB, with observable tuberculosis nodules, caseous necrosis, and inflammatory exudates at lung tissue. H&E × 100

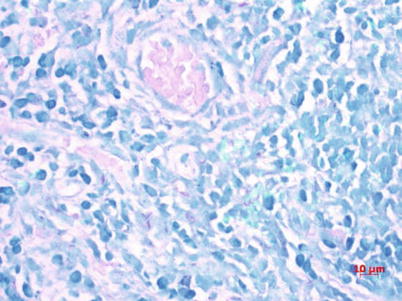

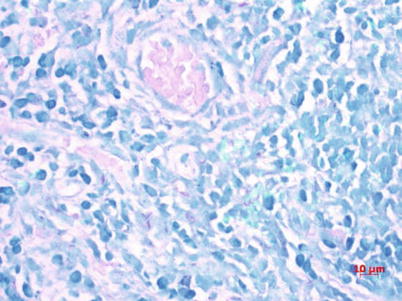

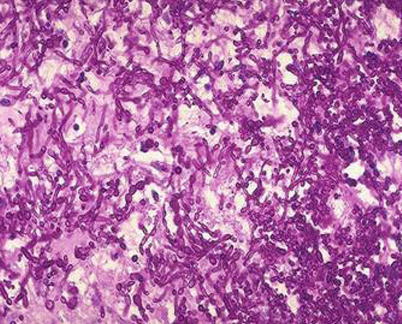

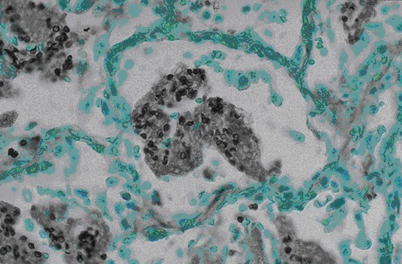

Fig. 5.3

Red short rod-shaped acid-fast bacilli after acid-fast staining

2.

AIDS complicated by MAC infection.

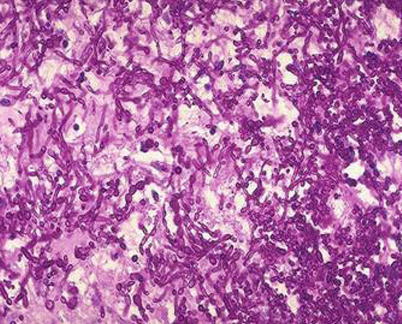

MAC, composed of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare, mainly causes pulmonary lesions, with the liver, spleen, gastrointestinal tract, lymph nodes, and other organs/tissues possibly involved. Nontuberculous mycobacteriosis is pathologically the same as tuberculosis. However, nontuberculous mycobacteriosis shows mild lesions like nodular hyperplasia of epithelioid cells, formation of non-caseous granulomas, hyperplasia and hyaline degeneration of collagen fibers, multifocal histiocytosis, and abundant vacuolated or foamy cytoplasm (Fig. 5.4). Acid-fast staining demonstrated a large quantity of red mycobacteria in the cytoplasm.

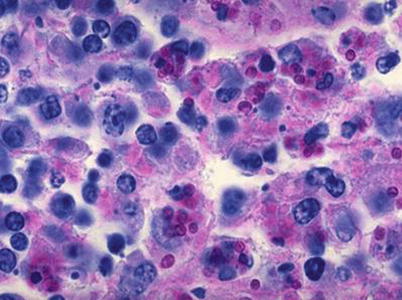

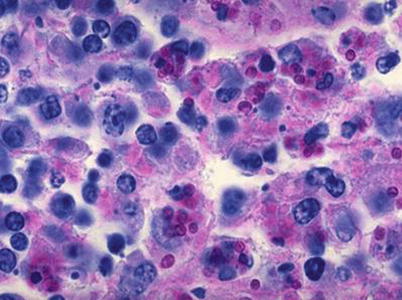

Fig. 5.4

MAC infection in lymph nodes of AIDS patients, with poorly defined nodular lesions due to hyperplasia of epithelioid cells but no non-caseous necrosis. H&E × 400

AIDS Complicated by Fungal Infections

1.

Moniliasis

Moniliasis is the most common fungal infection in AIDS patients. The lesions are commonly found at the oral cavity, throat, esophagus, and lungs, occasionally involving the central nervous system. Otherwise, disseminated moniliasis may occur. Pseudomycelium and blastospore can be detected in the affected tissue (Fig. 5.5).

Fig. 5.5

Esophageal Candida albicans infection. PAS staining × 200

2.

Cryptococcosis

The pathological changes caused by cryptococcosis mainly include exudative or granulomatous responses. Infiltration of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells can be observed in the lesion. The granulomas and even macrophages can be found to contain Cryptococcus, which has a spherical or ovoid shape with thick capsule surrounded by halo. Cryptococcus is stained red by PAS staining (Fig. 5.6) and black by silver staining.

Fig. 5.6

Cryptococcal meningitis, with Cryptococcus spores and their budding. PAS staining × 200

3.

Histoplasmosis

A considerable number of macrophages proliferate in the lesions to phagocytose histoplasma, and epithelioid cells are formed. And even Langerhans-type multinucleated giant cells aggregate into granuloma. Caseous necrosis may be observed at central part of some lesions, with peripheral fibrosis. The small round or oval yeast-like spores of Histoplasma have a diameter of 1–5 um and are surrounded by non-stainable capsule-like substance. The spores are reproduced by budding (Fig. 5.7).

Fig. 5.7

Histoplasma capsulatum in Kupffer cells. PAS staining × 400

4.

Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia (PCP)

PCP is clinically characterized by alveolar pneumonia and interstitial pneumonia, with pathological findings of pinkish foamlike or honeycomb-like substances filling in the alveolus (Fig. 5.8). In addition, alveolar epithelial cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, histiocytes, or alveolar macrophages shed in the alveolus wherein Pneumocystis can be identified by methenamine silver staining (Fig. 5.9).

Fig. 5.8

Infection of Pneumocystis carinii, with exudates in alveolar space. H&E × 400

Fig. 5.9

Pneumocystis carinii revealed as black cyst in the alveolar exudates. Silver staining × 400

AIDS Complicated by Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii is a parasitic protozoa that can cause toxoplasma encephalitis, toxoplasma myocarditis, toxoplasma pneumonia, and other diseases. Toxoplasma encephalitis is more common and is the major cause of death in patients with AIDS. Microscopic examination reveals degeneration and necrosis of nerve cells in the malacia lesion, inflammatory hyperemia surrounding the lesions, infiltration of lymphocytes, as well as hyperplasia of microglia, wherein pseudocapsule and bradyzoite can be found (Fig. 5.10).

Fig. 5.10

Toxoplasma encephalitis, with a cystic Toxoplasma containing a large quantity of Toxoplasma bradyzoites that appear like fine particles. H&E × 400

5.4.2.3 AIDS Complicated by Malignancies

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

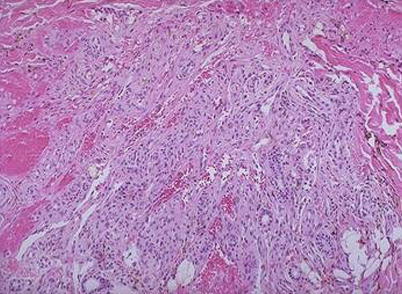

Kaposi’s sarcoma mainly locates at the skin of limbs. However, in some cases at the advanced stage, the condition may be accompanied by widespread involvement of other organs. The lung, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tracts are the commonly involved organs. Microscopic examination reveals the basic histological components of the neoplasm, including tumor blood vessels and sarcoma-type spindle cells (Fig. 5.11).

Fig. 5.11

Cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma that locates in the dermis, with predominant component of spindle cells and with vascular fissure and leakage of red blood cells H&E × 200

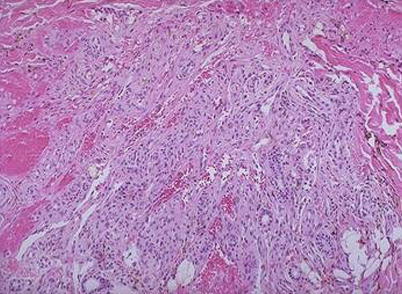

5.4.2.4 AIDS Complicated by Lymphoma

The incidence lymphoma in patients with AIDS is 5–20 %, which is the most commonly non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma (NHL) (Fig. 5.12), followed by Burkitt’s lymphoma (Fig. 5.13). Other possible lymphomas occurring in patients with AIDS include T-cell lymphoma or non-T-/non-B-cell lymphoma.

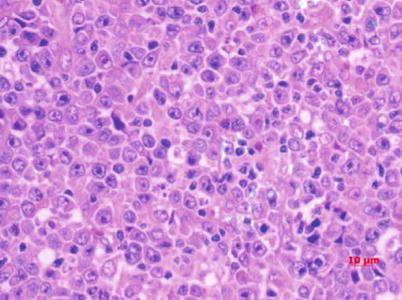

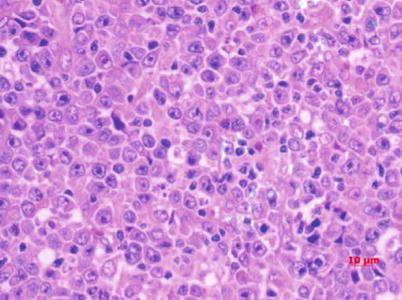

Fig. 5.12

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with a large-sized tumor cells and obvious nuclei. H&E

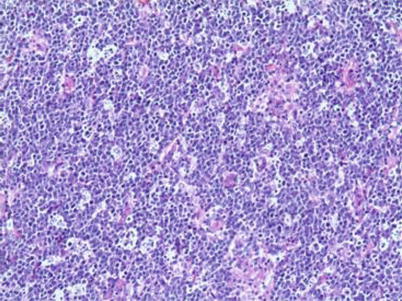

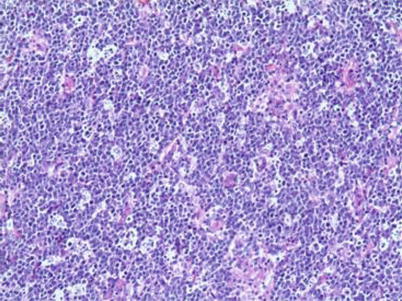

Fig. 5.13

Burkitt’s lymphoma of lymph node composed of B cells with uniform morphology and moderate size, with considerable B cells at mitotic phase that appears like stars in the sky. H&E × 200

5.5 Laboratory Tests

5.5.1 HIV Antibody Test

The commonly used HIV antibody tests include standard HIV screening test and confirmatory test. Standard HIV screening test, with a higher sensitivity and comparatively lower specificity, includes enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), rapid HIV test, and particle agglutination test. The confirmatory test, which is commonly achieved via Western blot (WB) and less commonly by strip immunoblot assay (SIA) or linear immunoblot assay (LIA), has a higher specificity but lower sensitivity. ELISA with a higher sensitivity in combination with WB with a higher specificity shows a diagnostic accuracy of up to 99 % and a false-positive rate of 0.0006 %. By such a combination test, there is almost no chance of misdiagnosis.

5.5.2 HIV P24 Antigen Detection

Various methods can be used to detect P24 antigen, including ELISA, immune complex dissociation (ICD), ultra-sensitive enzyme immunoassays (UEI), immunosorbent electron microscopy (ISEM), and lineal immunoenzymatic assay. HIV P24 antigen detection acts primarily as an assistant examination for the diagnosis of HIV infection during its window period. Meanwhile, it plays an important role in early diagnosis of HIV infection, monitoring the disease progression, predicting the prognosis, identifying neonatal infection, assessing the possibility of mother-to-child vertical transmission, evaluating therapeutic efficacy or newly developed vaccines, and basic mechanism of HIV/AIDS.

5.5.3 HIV Nucleic Acid Detection

HIV nucleic acid can be quantitatively or qualitatively detected, and the commonly used methods include RT-PCR, NASBA NucliSENS, bDNA, and real-time PCR. It is performed for the following purposes:

The diagnosis of infant HIV infection

The early diagnosis of HIV infection

The diagnosis of highly suspected cases with primary infection but negative or uncertain results by HIV antibody test

The assistant test for the diagnosis of cases with high-risk behaviors or exposure history, especially the cases with corresponding clinical manifestations

The assessment of disease progress and therapeutic efficacy of antiviral therapies

5.5.4 CD4 T-Cell Count and CD8 T-Cell Count

CD4 and CD8 T-cell count can be examined by flow cytometry assay and non-flow cytometry assay. Automatic detection is commonly performed by using flow cytometer (poly-platform or mono-platform) and specialized cell counter.

CD4 T-cell count and CD8 T-cell count are used for staging HIV infection, grading pediatric immunosuppression, assistantly assessing the therapeutic efficacy and disease progression, as well as evaluating the risk of opportunistic infections.

5.6 Clinical Diagnosis of HIV/AIDS

5.6.1 Principles of Diagnosis

The diagnosis of HIV/AIDS can be defined in combination with the epidemiologic history, including history of unsafe sexual behavior, history of intravenous drug abuse, history of infusing blood or blood products that are not tested for HIV, children of anti-HIV-positive parents, and history of occupational exposure. The clinical symptoms and laboratory test results should be comprehensively and diligently analyzed for the diagnosis. The cases that are tested HIV/AIDS positive should receive confirmative test. Nucleic acid test and HIV p24 antigen test facilitate the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS, which can help to effectively shorten the “window period.” Meanwhile, both tests can also facilitate the early diagnosis of neonatal HIV infection.

5.6.2 Diagnostic Criteria

5.6.2.1 Acute Stage

A patient who has a recent epidemiological history and symptoms, in combination to positive finding of anti-HIV antibody, can be diagnosed with HIV infection. Otherwise, based only on positive laboratory finding of anti-HIV antibody, the diagnosis can be made.

5.6.2.2 Asymptomatic Stage

A patient with an epidemiological history, in combination to positive finding of anti-HIV antibody, can be diagnosed with HIV infection. Otherwise, based only on laboratory finding of positive anti-HIV antibody, the diagnosis can be made.

5.6.2.3 AIDS Stage

A patient with an epidemiological history, in combination to anti-HIV antibody positive and the following one condition, can be diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Otherwise, based on the laboratory findings of HIV antibody positive and CD4 T-cell count <200 cells/μl, the diagnosis can be made.

1.

Persistent and irregular fever with no known cause and a body temperature > 38 °C for above 1 month

2.

Chronic diarrhea, with a frequency of >3 times per day, for above 1 month

3.

A weight loss by at least 10 % within 6 months

4.

Repeated occurrence of oral candida infection

5.

Repeated occurrence of herpes simplex virus or herpes zoster virus infection

6.

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP)

7.

Occurrence of bacterial pneumonia

8.

Development of active TB or non-mycobacterium tuberculosis

9.

Deep fungal infection

10.

Experiencing symptoms of central nervous system lesions

11.

Developing dementia in young and middle-aged adults patients

12.

Developing active cytomegalovirus infection

13.

Toxoplasma encephalopathy

14.

Occurrence of penicillium (such as Penicillium marneffei) infection

15.

Repeated occurrence of sepsis

16.

Kaposi’s sarcoma at skin mucosa or organ, lymphoma

5.7 Radiological Demonstrations

5.7.1 Chest

The lesions at chest of patients with HIV/AIDS diversify and the lungs are the most affected organ. The related pathogens include parasite, fungus, mycobacterium, virus, bacteria, and Toxoplasma gondii.

5.7.1.1 Opportunistic Infection

Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia (PCP)

Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is the most common pulmonary condition complicating HIV/AIDS, which often causes disabilities or even death. Pathologically, it is characterized by diffuse lesions at both lungs, filled pulmonary alveoli and bronchiole by foamy substances that are composed of dead bacteria and immunoglobulin and alveolar exudates with plasma cells, leukocytes, and histiocytes. The disease develops rapidly, with formation of typical alveolar effusive lesion within several days.

Typical CT Demonstrations of Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia

The diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of high-resolution CT for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia are 100 %, 83.3 %, 90.5 %, and 100 %, respectively. And the most characteristic demonstration is intrapulmonary ground glass opacity, which represents the early stage of alveolar infiltration (Fig. 5.14).

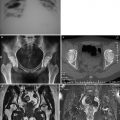

Fig. 5.14

(a–d) A male patient aged 31 years with AIDS complicated by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest CT showed extensive ground glass opacity in both lungs

It was once believed that lung air sac is uncommon in patients with HIV/AIDS complicated by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. However, with the development of detection techniques, the occurrence of lung air sac in patients with HIV/AIDS complicated by PCP is increasing, with an incidence rate of 10–34 %. It is, therefore, another common CT demonstration in addition to ground glass opacity characteristically of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. The demonstration of lung air sac in such patients is diverse, with thin sac wall, intact and smooth lining and outer wall, no liquid, and other substances in the sac cavity. The lung air sac may be demonstrated as singular, multiple, or honeycomb-like lesion that is commonly located at the subpleura or pulmonary parenchyma. The lung air sac is commonly distributed at the upper lung lobes, possibly with any lung lobes involved (Fig. 5.15). The mechanism underlying its occurrence remains unknown, which is speculated to be a pulmonary parenchymal response to Pneumocystis carinii. The response exhibits pulmonary alveolar or interstitial inflammation and different degrees of fibrosis that leads to remodeling of lung structures to develop cystic or honeycomb-like lesion. Lung air sac may occur at any stage of infection, commonly surrounded by different degrees of ground glass opacity. After effective treatment, lung air sac can repair itself and be cured.

Fig. 5.15

(a, b) A female patient aged 23 years with AIDS complicated by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Chest CT demonstrated extensive lung air sac and ground glass opacity in both lungs

Rupture of some subpleural lung air sacs may cause pneumothorax. Therefore, the finding of lung air sac or pneumothorax at the area of ground glass opacity in patients with AIDS strongly indicates Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

Atypical Demonstrations of Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia

The atypical demonstrations of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia are various and non-characteristic, which present challenge for its radiological diagnosis. The abnormalities at pulmonary parenchyma include:

1.

Pulmonary nodule or mass.

The diameter ranges from 2 to 3 mm miliary nodule to over 1 cm nodule with solitary or focal distribution. Histologically, the nodule manifests as granulomatous inflammation and its incidence rate is about 5 % in patients with Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. At the chronic stage, the nodule is calcified. In the cases with disseminated infection, it may occur at the liver, spleen, or kidney.

2.

Segmental inflammation.

It commonly occurs at upper lobes of both lungs with one lobe or segment as a unit.

3.

Interstitial fibrosis.

It occurs in patients with chronic Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia that lasts for several months or even several years. And it could also be sequelae of fibrosis or pulmonary cystic lesion after treatment for acute Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Interstitial fibrosis manifests as thickened interlobular septum, blurry reticular opacity, tractional bronchiectasis, and honeycomb-like lesion.

4.

Bronchial abnormalities.

The bronchial abnormalities include bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis obstruction, and endobronchial lesion.

5.

Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenectasis. The lesions are commonly mild.

Types of Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia

Lu PX et al. categorized Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia into 5 types based on its CT demonstrations, including ground glass opacity type, lung air sac type, consolidation type, interstitial type, and mixed type. The ground glass opacity type is the most common characteristic, with symmetrically distributed opacities with increased density in the lungs and bronchovascular bundles inside. The lung air sac type shows thin-wall air sac, with intact and smooth lining and outer wall but no liquid level in the sac. The sac is commonly surrounded by different degrees of ground glass opacity and flaky infiltrative opacity. Lung air sac type has multiple lesions at both lungs that are more commonly found at upper lung lobes (Fig. 5.16). The consolidation type displays uneven patches of opacities at both lungs and segmental pneumonia with one lobe or segment as a unit. The interstitial type displays thickened interlobular septum and bilaterally asymmetric diffuse reticular or network-like nodular opacities, which may be complicated by consolidation (Fig. 5.17). The mixed type shows concurrence of above lesions, which is commonly found in patients at the advanced stage.

Fig. 5.16

(a–f) A male patient aged 39 years with AIDS complicated by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (lung air sac type). (a–d) Both lungs were demonstrated with multiple thin-wall air sacs, with septum in some sacs, surrounded by lung consolidation and ground glass opacity. Thickened interlobular septum and reticular nodular opacities were also shown. (e, f) Reexamination at d 30 after treatment, the lung air sacs were displayed to be obviously absorbed and improved

Fig. 5.17

(a, b) A male patient aged 45 years with AIDS complicated by Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Both lungs were displayed with small nodular opacity and ground glass opacity

The categorization entails the pathological changes and the dynamic CT findings of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, which is significant for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

Tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is still an important respiratory pathogen in patients with HIV/AIDS. HIV infection has been known to be one of the most dangerous factors inducing development of latent tuberculosis into active tuberculosis. The radiological demonstration of HIV/AIDS complicated by tuberculosis is related to the immunity of patient. At the early stage of AIDS, the radiological demonstration resembles to tuberculosis in patients with normal immunity. At the middle and advanced stages of AIDS, the patient’s immunity is moderately or seriously suppressed. Therefore, tuberculosis is radiologically displayed as intrapulmonary infiltration as well as hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectasis with no definite location.

Primary Tuberculosis

Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectasis may be singular or multiple. In the cases with multiple hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectasis, the lesions are extensive and may integrate into mass. By CT scan, 70–90 % of patients with primary tuberculosis have hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectasis, and the calcification rate of enlarged lymph nodes is much lower than that of simplex tuberculosis. CT plain scan demonstrated the enlarged lymph nodes with low density. By contrast scan, marginal ring-shaped enhancement is commonly shown, with central low-density caseous necrosis (Fig. 5.18). Intrapulmonary infiltration commonly occurs at vulnerable sites of non-simplex tuberculosis, such as the lower lung lobes or right middle lung lobe. Multiple lung segments and lobes may be concurrently involved. The lesions progress rapidly that are commonly exudative consolidation. In some cases, signs of bronchial dissemination may be demonstrated, such as acinar nodular opacity and tree-bud sign. However, the signs of fibrosis and calcification are rarely shown.

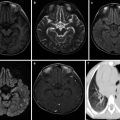

Fig. 5.18

(a–d) A male patient aged 34 years with AIDS complicated by lymphoid tuberculosis. Chest CT plain and contrast scan showed integration of multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum, posterior to major bronchus and adjacent to thoracic aorta, with obvious enhancement

Secondary Tuberculosis

At acute and asymptomatic stages of HIV infection, the radiological demonstration of secondary tuberculosis resembles to tuberculosis in patients with no HIV infection due to slightly suppressed immunity of the patients. The lesions are often located at the apicoposterior segment of the upper lung lobe or dorsal segment of the lower lung lobe, displayed as flaky focal consolidation and nodule opacities. Cavity has an incidence rate of 20–25 %, while lymphadenopathy and extrapulmonary lesions have an incidence rate of 10–15 %. Along with continual decrease of peripheral CD4 + T-cell count, patients with AIDS experience increasingly serious cellular immunodeficiency. Therefore, the complication of tuberculosis may be radiologically demonstrated as more extensively severe and atypical lesions. The lesions are radiologically characterized by no definite location, diversified morphology, common progression into thin-wall or irregular no-wall cavity, and common occurrence of hilar and mediastinal lymphadenectasis. CT scans show involvement of multiple lung lobes or segments. Lesions with various morphologies can be simultaneously demonstrated, including infiltrations and military and acinar nodule dissemination. In addition, caseous pneumonia is common (Fig. 5.19). Radiologically, the lesions are generalized into “three multis and three rares”: concurrence of multiple lesions (including exudation, proliferation, and cavity), multiple morphology, and multi-segmental distribution but rare occurrence of fibrosis, calcification, and mass-like opacity. The cavity may be singular or multiple and multiple cavities are more common. The cavities commonly scatter within the lungs, especially the upper and middle lung lobes (Fig. 5.20). Lymphadenectasis at lung hilus and mediastinum has a high incidence rate (Fig. 5.21), which is 17–69 % in patients with AIDS complicated by tuberculosis, but only 3–23%in patients with simplex tuberculosis. CT plain scan showed enlarged lymph nodes with homogeneous and slightly low density. By contrast CT scan, irregular ring-shaped enhancement can be displayed but no enhancement of the central caseous necrosis.

Fig. 5.19

(a–e) A female patient aged 24 years with AIDS complicated by consolidation type of tuberculosis and left pleuritis. By sputum culture, the acid-fast bacillus was positive (+); (a) consolidation opacity was displayed at the lingual lobe of the left lung that was surrounded by pulmonary acinar nodules; (b) a small quantity of pleural effusion was shown in the left pleural cavity; (c) biopsy after CT-guided puncture was performed; (d) pathology showed granulation tissue and caseous necrosis that are in line with tuberculosis (H&E × 100); (e) reexamination after antituberculosis and antiviral therapies for more than 1 year showed cord-like opacity at the lingual lobe of the left lung but no pleural effusion

Fig. 5.20

(a, b) A female patient aged 27 years with AIDS complicated by cavity type of tuberculosis in the left lung. Chest CT scan showed large irregular flaky opacity at the left upper lung lobe with multiple cavities inside

Fig. 5.21

A male patient aged 33 years with AIDS complicated by tuberculosis. (a–e) Chest CT scan showed multiple patches of and nodular opacities at the upper and middle lobes of both lungs and mass-like high density and opacity at right lung hilum. (f, g) Reexamination after antituberculosis therapy for 6 months displayed almost complete absorption of lesions

Fungal Infection

The fungi invading the lung of patients with AIDS commonly include cryptococcus, histoplasma, candida, aspergillus, yeast, and coccidioides.

Pulmonary Cryptococcosis

It is a common deep fungal infection and commonly concurs with meningitis. Radiologically, the lesions are characterized by various shapes, various kinds, and multiple different-sized foci.

By CT scan, pulmonary cryptococcosis manifests solitary mass-like opacity, singular or multiple nodular opacities, singular or multiple patches of infiltration opacity, diffusive miliary nodule opacity, interstitial pneumonia, and diffusive mixed lesions. The nodular opacities are commonly well defined but morphologically irregular with different sizes and a diameter of about 5–60 mm or larger. Some of the nodular opacities are lobulated and have spikes. The patches of infiltration opacity may be demonstrated as small strips or flakes with the singular or multiple lung lobes involved. The opacity is poorly defined with inhomogeneous density, possibly with observable bronchus sign or vacuole sign. By HRCT, the diffuse miliary nodules are displayed as poorly defined acinar nodules with homogeneous density and a size of 3–5 mm, which resemble to lesions of pneumonia or miliary tuberculosis. Diffuse mixed lesions refer to coexistence of nodules, patches, mass, and lobar consolidation, in which solitary or multiple lung nodules are the most common sign by CT scan. The second common signs include mass and consolidation. The rare CT signs include cavity, calcification, hydrothorax, and hilar/mediastinal lymphadenectasis (Fig. 5.22).

Fig. 5.22

(a–c) A male patient aged 33 years with AIDS complicated by pulmonary cryptococcosis. Chest CT showed patches and nodular blurry opacities at both lungs, mediastinal lymphadenectasis, and pleural effusion

Simplex involvement of the lungs is rare, accounting for about 5–10 %. About 40 % of the patients also experience pleuritis.

Histoplasmosis

In patients with AIDS, histoplasmosis may be hematogenously disseminated to involve multiple organs and induce pneumonia. The condition is commonly accompanied by systemic lymphadenectasis, hepatosplenomegaly, meningitis, pericarditis, or endocarditis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree