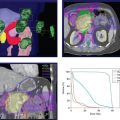

FIGURE 17-6c. CTV1 and CTV2 delineation in a 55-year-old man with T2N0M0 squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal who underwent definitive chemoradiotherapy with IMRT.

1. ANATOMY

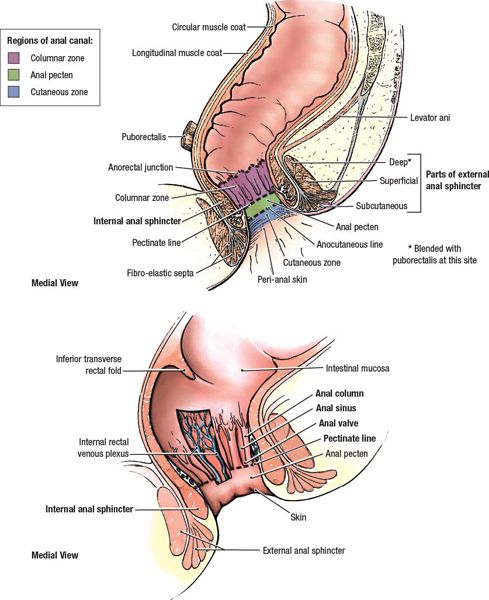

• The anal canal extends from the rectum to the perianal skin, and is 3 to 4 cm in length. The proximal margin is at the dentate (pectinate) line, which is at the level of the puborectalis muscle of the anorectal sling. The distal margin is the anal verge. Epithelium of the anal canal is a modified, nonkeratinized squamous epithelium. Around the dentate line, there is a transitional zone with epithelium containing rectal, urothelial, and squamous features. Above the dentate line, glandular mucosa predominates within the rectum.

• Anal margin (or perianal skin) is defined as 5 cm radius around the anal verge. Histologically, the perianal skin is similar to hair and gland-bearing skin elsewhere.

• Blood supply within the anal region contains anastomoses between the portal and systemic venous systems. Venous plexuses in the proximal anal canal drain to the portal system through the superior rectal vein and inferior mesenteric vein, while the anal canal distal to the dentate line drains to the systemic system through the internal pudendal and internal iliac veins (see Fig. 17-1).

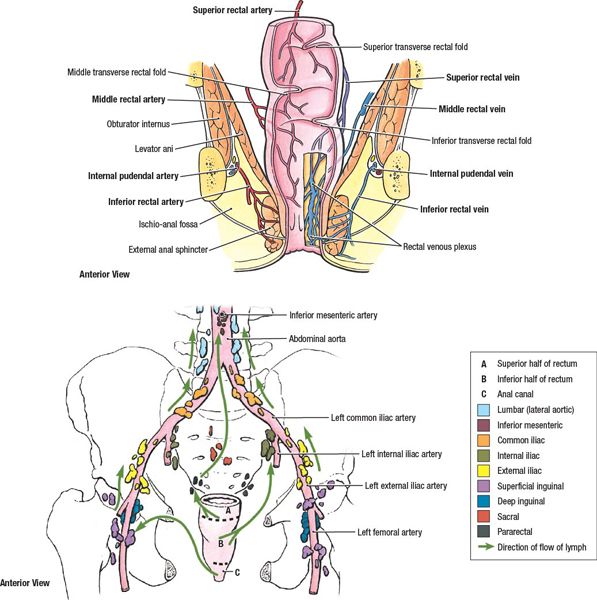

• Lymphatics from the perianal skin and anal canal distal to the dentate line drain to primarily the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, with less common drainage directly to femoral and external iliac nodes. Proximal to the dentate line, lymphatics drain to the perirectal, internal pudendal, hypogastric, and obturator lymph nodes of the internal iliac system (see Fig. 17-2).

• Anorectal continence is maintained through voluntary and autonomic control. The striated muscles of the external sphincter are under voluntary control, and are innervated by the inferior rectal nerve (a branch of the pudendal nerve that arises from S2, S3, and S4). Smooth muscle of the internal sphincter is under the control of parasympathetic nerves from S2-4 and sympathetic fibers from the hypogastric plexus.

FIGURE 17-1. Anatomy of anal canal and sphincter. (Reprinted from Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:211.)

FIGURE 17-2. Lymphatic drainage of the rectum and anal canal. (Reprinted from Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:213.)

2. NATURAL HISTORY

• It was estimated that 7,060 new cases of cancer of the anus, anal canal, and anorectum will be diagnosed in 2013, with 880 deaths from the disease. This accounts for approximately 2.2% of all gastrointestinal cancers.1 Anal canal cancers are three to four times more common than those arising in the perianal skin.

• The incidence rate of invasive anal carcinoma in the United States has increased 1.9-fold for men and 1.5-fold for women from 1973–1979 to 1994–2000.2

• Risk factors for anal carcinoma include

º Infection with high-risk subtypes of human papilloma virus (especially HPV 16 and 18). HPV 16/18 DNA has been found in 72% to 84% of anal cancer specimens in systematic reviews.3–5

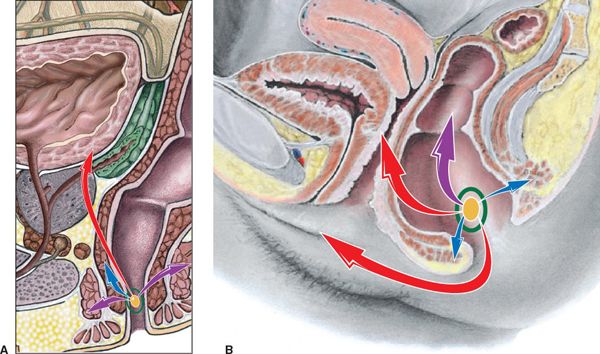

FIGURE 17-3. Patterns of spread for anal cancer. (A) Male. (B) Female. T-stages are indicated by colored arrows: Tis, yellow; T1, green; T2, blue; T3, purple; T4; red. (Reprinted from Rubin P, Hansen JT. TNM Staging Atlas with Oncoanatomy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012:363.)

º Immunosuppression, particularly with chronic use of immunosuppressive drugs6 or HIV,7 facilitates persistent infection with HPV.8

º Tobacco smoking is associated with a five-fold increase in anal cancer.9

º Benign anal conditions and inflammatory bowel disease do not appear to be associated with an increased risk of squamous cell anal cancer.10–12

• Squamous cell carcinoma comprises approximately two-thirds of anal cancer, with transitional (cloacogenic) carcinomas accounting for one-fourth of anal cancer. Adenocarcinoma can arise from anal crypt cells and account for 5% to 7% of cancers of the anal canal. Melanoma, lymphoma, and neuroendocrine tumors rarely occur.

• Anal squamous cell carcinoma is usually preceded by high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). The rate of progression from AIN to invasive cancer is approximately 1% per year.

• Local extension of tumor and lymphatic spread are more common than hematogenous dissemination.

º At the time of presentation, pelvic lymph node metastases are found in 30% of patients; inguinal lymph node involvement is seen in 15% to 35% of patients.13

º About 10% of patients present with extrapelvic visceral metastases. Anal cancer most commonly metastasizes to the liver and lungs.

• Figure 17-3 illustrates the patterns of spread by T-stage of anal cancer.

3. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING WORKUP

3.1. Signs and Symptoms

• History: The most common presenting symptoms are bleeding and anal pain; other symptoms include pruritus ani and the presence of a palpable mass.

• Physical examination (including digital rectal exam and regional lymphatic nodal palpation), with evaluation of risk factors for HIV infection when applicable. Pelvic gynecologic examination in women to evaluate for involvement of the rectovaginal septum, as well as screening for cervical cancer.

3.2. Additional Workup

• Proctoscopy with biopsy of the primary tumor. Evaluation of HPV status of the tumor should be obtained.

• Biopsy of inguinal lymph nodes, if clinically suspicious.

• Blood work should include complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel and liver function tests. HIV testing should be considered if risk factors present. HIV-positive patients should have CD4 count quantified before start of treatment.

3.3. Imaging

• Chest x-ray

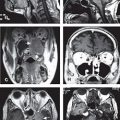

• Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis

• Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is useful in diagnosis of nodal disease and distant metastases. It upstages 17% of CT-staged N0 patients to N+.14 Comparing MRI staging in 88 patients, Bhuva et al.15 showed that PET/CT changed staging in 42% of patients, predominantly though changes in N staging. Sveistrup et al.16 reported a series of 95 patients in which PET/CT upstaged the disease in 14% of cases, and changed the treatment plan in 17% of cases. At present time, however, the 2012 NCCN guidelines does not consider PET/CT a replacement for diagnostic CT.

• Transanal ultrasound has not been validated as a staging tool, but can identify the depth of tumor invasion.17

3.4. Staging

• American Joint Commission on Cancer’s (AJCC) 7th edition of staging guidelines is unchanged from the 6th edition for anal canal cancer.18

• Staging of the primary site is predominately based on the size of the tumor. T1 tumors are 2 cm or smaller; T2 tumors measure 2 to 5 cm; T3 are over 5 cm in diameter. Tumors invading adjacent organs (excluding the perirectal skin, rectal wall, sphincter or subcutaneous tissues) are staged as T4.

• Regional lymph nodes include perirectal (anorectal, perirectal, and lateral sacral), internal iliac (hypogastric), and inguinal chains. Perirectal nodal involvement alone is N1; unilateral internal inguinal and/or iliac involvement is N2; bilateral nodal involvement or perirectal and inguinal nodal involvement is N3. All other nodal groups represent sites of distant metastasis.

• Perianal tumors are biologically similar to other skin cancers, and are staged in the same manner as cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. Please refer to AJCC guidelines (7th edition) for an update on staging of skin cancer.18

4. PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

• The presence of extrapelvic metastatic disease is the strongest predictor of poor prognosis.2,19

• In patients with nonmetastatic disease, higher T- and N-stages were independently associated with higher probability of locoregional failure. Higher N-stage was also associated with distant metastases and lower overall survival.20

• Basaloid histology has been associated with higher incidence of distant metastases.20

• Increasing age and decreasing performance status are associated with poorer survival.

• Women have better prognosis than men.

• Hemoglobin levels <130 g/L at diagnosis have been found to be associated with decreased progression-free survival, distant relapse-free survival, and overall survival.21

• The literature is discrepant regarding the association of low CD4 count and high HIV viral load with local control, survival, and impaired tolerance of chemoradiation.22–32

5. MANAGEMENT

• Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation has replaced upfront abdominal–perineal resection. With high cure rates, the anal sphincter is preserved and colostomy is avoided.

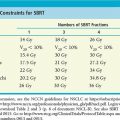

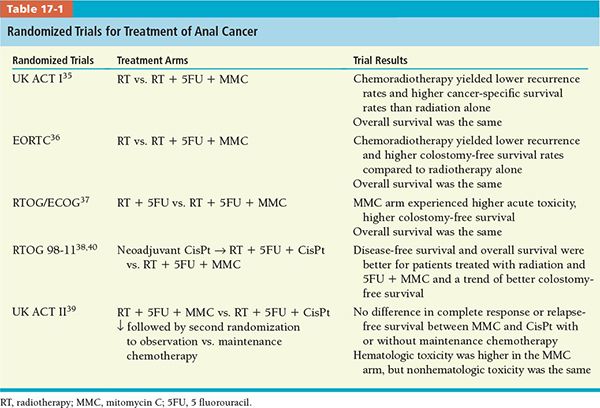

• This standard of care has been pioneered initially by Nigro et al.33,34 at Wayne State University and later consolidated by institutional experience and randomized trials (Table 17-1).35–39

• At present time, the standard approach for treating anal canal cancer is a combination of concurrent radiotherapy and systemic chemotherapy administered in week 1 and 5 of radiation consisting in 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and mitomycin-C (MMC).

• Alternative chemoradiation regimens have been tested in a continuing effort to avoid significant toxicity associated with MMC.

• Cisplatinum is a cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent with radiosensitizing effects. It has been tested in combined modality regimens for anal canal cancers, in an attempt to replace MMC and improve toxicity profile. UK ACT II and RTOG 98-11 randomized trials showed better outcome with 5FU/MMC versus 5FU/cisplatin39,40 (Table 17-1).

• Therefore, MMC and 5FU administered concomitantly with radiotherapy remain the preferred modality of treatment of anal canal cancer.

6. INTENSITY-MODULATED RADIATION THERAPY

• Traditionally, radiotherapy (RT) was administered using two-dimensional planning (fields designed based on bony landmarks) and three-dimensional (3D) planning (guided by CT images obtained at the time of simulation). The treatment plan consisted parallel opposed pelvic fields, with anterior larger port to include pelvic and inguinal areas in addition to the tumor. Posterior field was narrower to avoid the femoral heads and the dose to inguinal areas was supplemented by en face electron fields.

• Toxicity from the treatment has been significant, leading to treatment interruptions, increase in overall treatment time, and lower total dose administered, with negative impact on disease control.

• For anal cancer, correlation has been found between overall treatment time, total dose administrated, and the risk of colostomy and local control.41–43 Subsequently, minimizing toxicity from radiotherapy is important to allow dose escalation and shorter treatment time.

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree