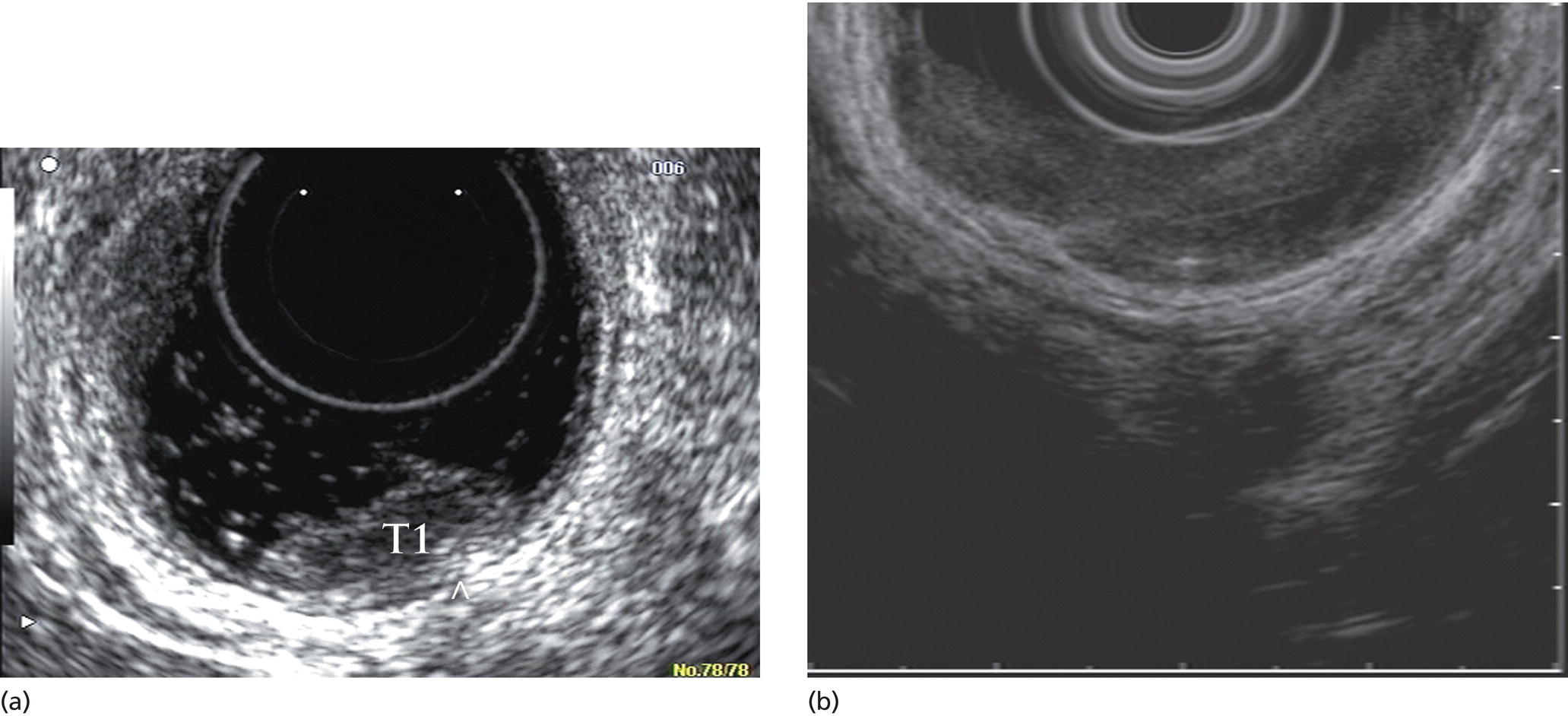

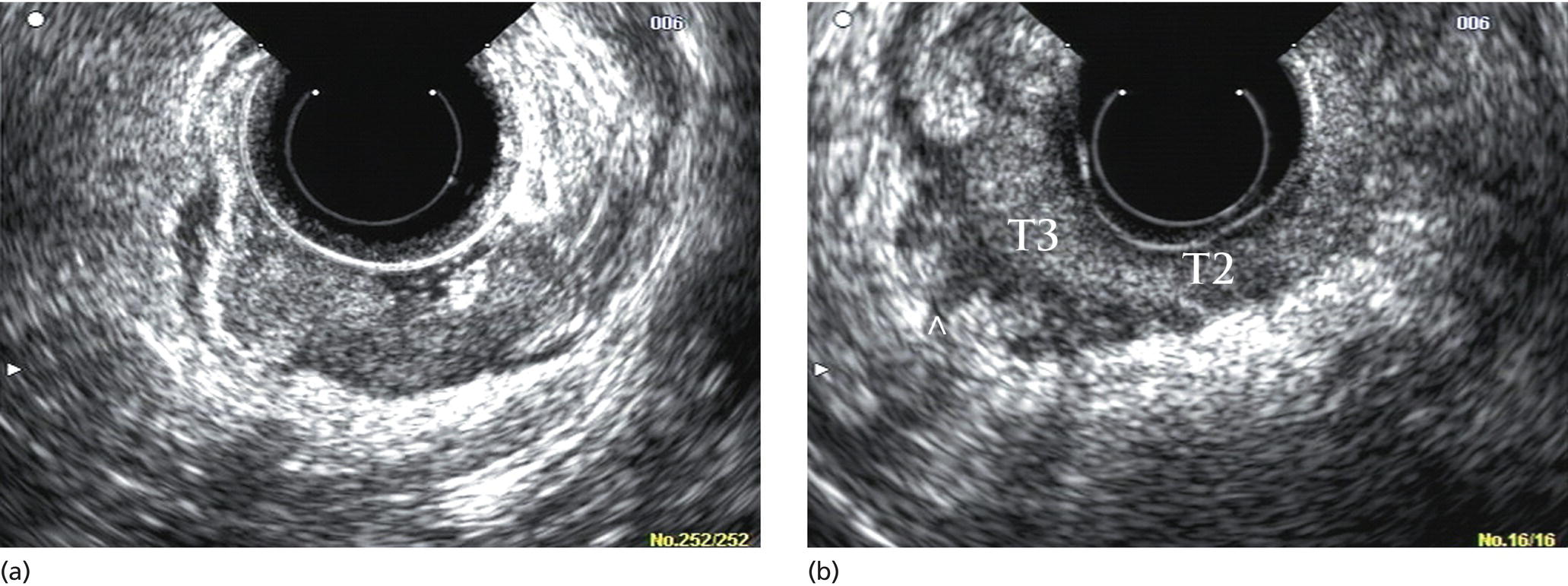

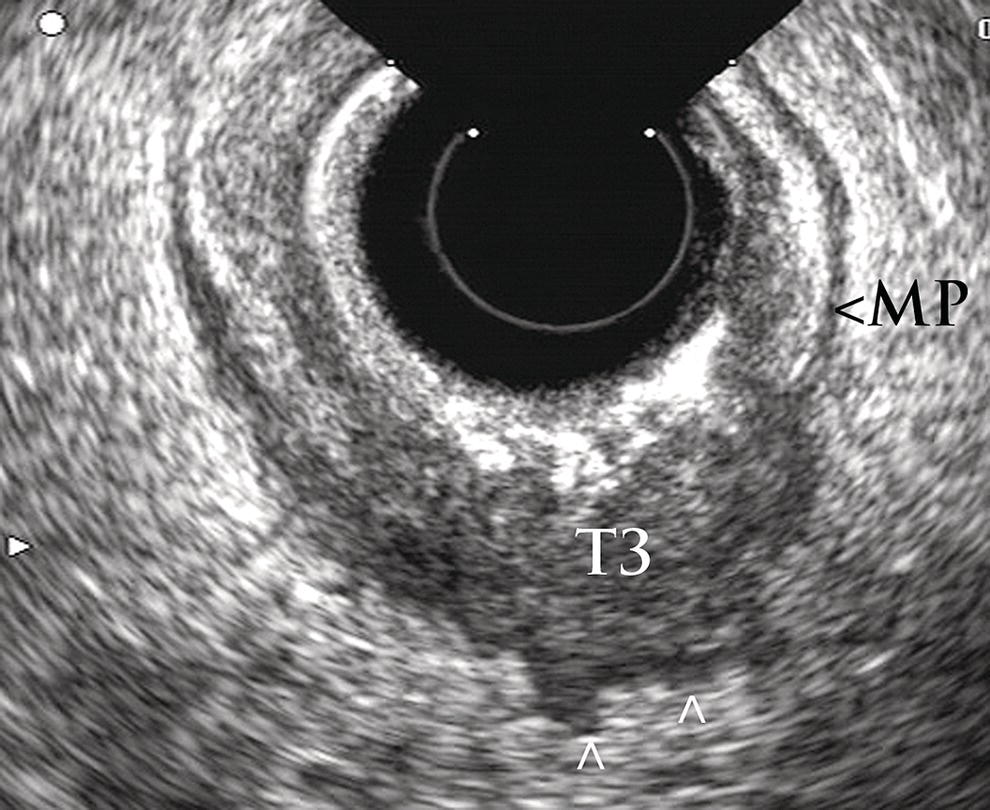

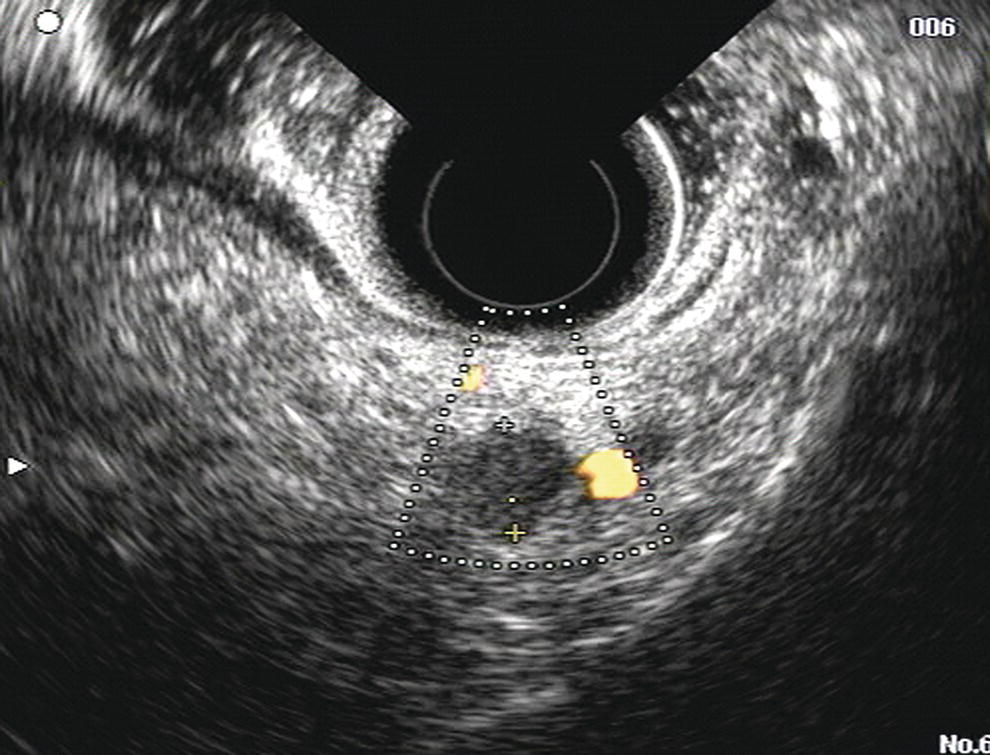

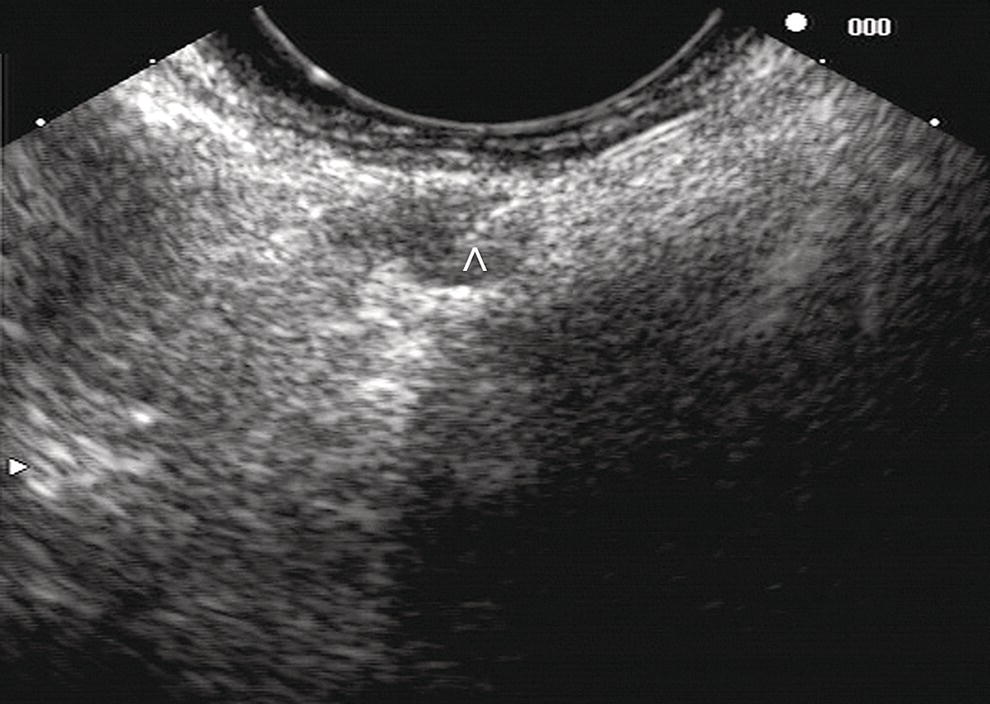

Manoop S. Bhutani1 and Everson L.A. Artifon2 1 University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA 2 University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil and Ana Costa Hospital, Santos, Brazil Malignant colorectal tumors by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) appear as hypoechoic masses. A tumor that by EUS appears to be limited to the mucosa or the submucosa (first three echo layers) is classified as a T1 lesion by EUS (Figure 15.1). A colorectal carcinoma invading into the muscularis propria (hypoechoic fourth EUS layer) but with an intact outer margin of the muscularis propria and with no penetration completely through the muscularis propria will be a T2 lesion by EUS (Figure 15.2). A T3 lesion by EUS penetrates completely through the rectal wall and all the EUS layers, has irregular outer margins, or has tumorous pseudopodia extending beyond the five echo layers (Figures 15.2b and 15.3). A T4 lesion by EUS is a colorectal cancer that is locally invading into an adjacent organ, e.g. the prostate or vagina. Lymph nodes during EUS may be seen as round, oval, or sometimes triangular structures that may be hypoechoic, echogenic, or with mixed echogenicity. In addition, if color Doppler is available on the echoendoscope it may further help in differentiating a vascular structure from a lymph node by observing color flow within a vessel (Figure 15.4). When no lymph nodes are seen during EUS, or if the lymph nodes visualized during EUS are considered reactive and not malignant, the N stage is classified as N0. When lymph nodes visualized during EUS are believed to be malignant, N1 stage by EUS is diagnosed with one to three regional lymph nodes and N2 stage is diagnosed with four or more regional lymph nodes. In rectal cancer, the size cutoff for lymph nodes considered as suspicious for malignant invasion is 5 mm instead of 10 mm. The application of endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration (EUS‐FNA) may be used as an adjunct to accurate lymph node assessment during EUS and it has been applied in patients with rectal cancer (Figure 15.5 and Video 15.1). EUS‐FNA of lymph nodes is not an option for those in the immediate vicinity of the primary tumor since traversing of the EUS‐FNA needle through the primary will lead to false‐positive results. Local recurrence of colorectal cancer after attempted curative resection occurs in 2.6–32.0% of patients. Endosonography may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected local recurrence when no lesions arising from the mucosa are seen during conventional endoscopy. Endoscopic ultrasound in such cases may reveal hypoechoic areas (or areas of mixed echogenicity) outside the colorectal wall (Figure 15.6). Endosonographic alterations due to the primary surgery need to be kept in mind. The risk of recurrence after surgery for rectal cancer is greatest in the first two years after surgery. Detection of local recurrence in a resectable stage provides an opportunity for repeat surgery with curative intent. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation is often utilized for downstaging of a rectal cancer prior to surgical resection. Although EUS is very accurate in T and N staging for rectal cancer prior to initiating any treatment, restaging after chemoradiation is problematic. Inflammation and necrosis after chemoradiation appears hypoechoic and indistinguishable from malignant tissue. This results in the obvious problem of overstaging by EUS after radiation and chemotherapy. Figure 15.1 (a) A T1 rectal adenocarcinoma (by radial EUS) arising in a villous adenoma with an intact submucosa and muscularis propria (arrowhead) underneath. (b) A larger T1 rectal cancer (compared to Figure 15.1a) arising from the mucosa with an intact submucosa underneath the cancer. Figure 15.2 (a) A rectal adenocarcinoma that appears to be T2 (penetration into muscularis propria). (b) Radial EUS image of a rectal adenocarcinoma that appears to be T2 (penetration into muscularis propria) in one portion and T3 (penetration through the muscularis propria into perirectal fat as indicated by arrowhead) in another. It is difficult to predict the cause of an endoscopically visible bulge into the gastrointestinal lumen when the overlying mucosa is normal (Figure 15.7a). A lipoma is characterized by a homogeneous echogenic lesion that is contiguous with the third echo layer corresponding with the submucosa. Most lipomas are benign and malignant transformation is a rare phenomenon. Thus, there is controversy about the need for endoscopic removal once a lipoma is diagnosed by EUS. However, EUS would be a prerequisite prior to contemplating endoscopic removal of a lipoma. Endoscopic ultrasound may also help in monitoring this lesion if it is not removed. A myogenic tumor appears as a hypoechoic mass that is contiguous with the fourth echo layer representing the muscularis propria (Figure 15.7b). The differential diagnosis of a myogenic tumor includes a leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, leiomyoblastoma, or a gastrointestinal stromal cell tumor (GIST). A myogenic tumor that is greater than 4 cm in diameter and which has an irregular margin, with cystic or echogenic foci, is more likely to be a malignant lesion. However, there is overlap between benign and malignant myogenic or GIST lesions, and resection of the entire lesion is the surest way to ensure absence of malignancy. If, however, a decision is made to monitor a myogenic lesion that appears benign, EUS may be useful. Any change in echo features, such as size, echogenicity, margins, or appearance of lymphadenopathy, may then warrant a surgical resection. Figure 15.3 Radial EUS of a T3 lesion showing the primary rectal tumor penetrating through the muscularis propria (MP) into perirectal fat (arrowheads). Figure 15.4 Radial EUS of the patient in Figure 15.3 showing a 7‐mm round, perirectal, hypoechoic lymph node with no flow on color Doppler with an adjoining vessel nearby with color flow. Figure 15.5 EUS‐guided fine needle aspiration of a perirectal lymph node. The tip of the needle is within the lymph node (arrowhead). Carcinoid tumors of the rectum are not uncommon. They generally appear as a firm, small, submucosal nodule (Figure 15.8a). By EUS a rectal carcinoid appears as a hypoechoic mass arising from the second echo layer and sometimes compressing or extending to the submucosa (Figure 15.8b). Colonic lymphangiomas can also produce a submucosal compression. By endosonography they appear as multiple anechoic (cystic) lesions with echogenic septations located within the third echo layer corresponding with the submucosa. These lesions are generally benign and are left alone unless they cause symptoms such as bleeding, intestinal obstruction, or intussusception. The endosonographic image of a rectal lesion–colitis cystic profunda is similar to echo features of colonic lymphangiomas. There have also been isolated case reports of endosonography in colonic pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis and polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds associated with colonic diverticular disease. Recurrence of colorectal carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, and appendiceal mucocele may also cause submucosal elevation in the colorectum.

15

Anorectal Neoplasia

Colorectal cancer staging by EUS

Tumor (T) stage

N stage

Endoscopic ultrasound for local recurrence of colorectal carcinoma

Restaging after chemotherapy and radiation

Submucosal tumors of the colorectal wall

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree