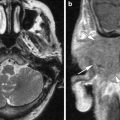

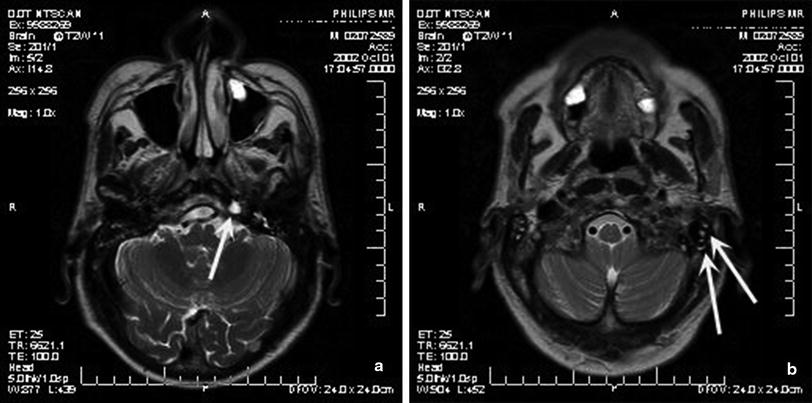

Fig. 1

The normal petrous apex as is it seen in most patients. On the CT images (a) the bone marrow in the petrous apex is obviously seen bilaterally (arrows). On the axial T1-weighted MR image (b) a hyperintense signal is noted bilaterally, lateral to the hyperintense clivus, indicating the presence of fatty bone marrow in the non-pneumatized apex (arrows)

2 Lesions of the Petrous Apex

Petrous apex lesions are rare, and they are often noted incidentally, unrelated to the presenting clinical manifestation (Leonetti et al. 2001). However, in the presence of petrous apex lesions, a variety of clinical symptoms is noted, such as hearing loss, dizziness, headaches, and tinnitus (Muckle et al. 1998). Usually, these lesions can be precisely defined using imaging techniques such as CT and MR. Although MR-guided biopsies through a transsphenoidal access have been attempted in the petrous apex region (Bootz et al. 2001), such procedures are usually unnecessary if an experienced radiologist studies the lesion. MR specifically plays an important role in the differentiation of petrous apex lesions, that can often be easily detected with CT, but where CT does not always permit to correctly differentiate the imaging finding (Pisanischi and Langer 2000). The importance of MR on this matter has been emphasized since the late 1980s and early 1990s (Griffin et al. 1987; Greenberg et al. 1988; Jackler and Parker 1992; Arriaga and Brackmann 1991). The study of the spontaneous signal intensities of these lesions on T1- and T2-weighted images and of the enhancement pattern of the internal matrix of the lesions often allows to provide a correct diagnosis with a very high degree of confidence (Curtin and Som 1995). Consequently, the radiologist plays an important role in the process of decision making, whether the area in question needs surgical therapy, and influences the process of deciding on the exact type of surgery that should be performed (Chang et al. 1998; Profant and Steno 2000; Brackmann and Toh 2002). MR scanning is helpful to evaluate for complete removal, complication, recurrence, or formation of complicating granulation tissue (Pisanischi and Langer 2000).

2.1 Don’t Touch Lesions

On the basis of MR, two ‘don’t touch’ entities in the petrous apex can be confused with pathologic lesions that need surgery: asymmetric presence of fatty marrow and trapped fluid in petrous air cells. Although both have specific imaging characteristics, radiologists do not always confidently define these two nonsurgical petrous apex lesions (Palacios et al. 2001; Moore et al. 1998).

2.1.1 Asymmetric Presence of Fatty Marrow

In case of asymmetric presence of fatty marrow, the radiologist should notice that the area with high signal in the petrous apex region has the same signal intensity as fat on all sequences (Roland et al. 1990; Moore et al. 1998) (Fig. 2). If still any doubt would remain, CT of the region can be performed and will show a less pneumatized petrous apex on the side that was considered suspicious on the MR examination. Fat-suppressed MR techniques can also give the solution.

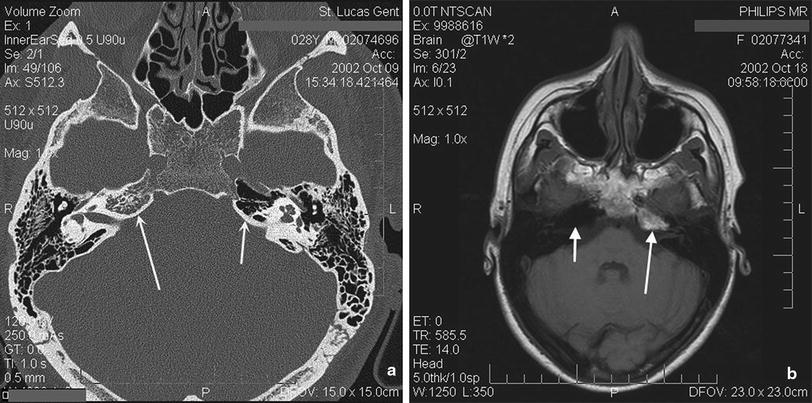

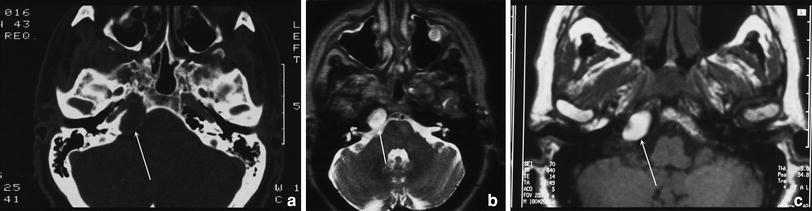

Fig. 2

Asymmetrical pneumatization of the petrous apex on CT (a), with pneumatization on the left side (small arrow) and non-pneumatization on the right side (large arrow). Note that on the T1-weighted MR image (b) a high signal is seen in the apex on the left side (large arrow), which should not be mistaken for tumor. The signal is identical to the one of fat in other locations (e.g., clivus, mandibular head, pterygopalatine fossa, etc.): normal fatty bone marrow in the non-pneumatized apex. The right petrous apex is pneumatized and shows no signal (small arrow)

2.1.2 Fluid-Filled Petrous Apex Air Cells

The petrous apex is aerated to a variable degree. It is believed that the degree of aeration as such is not responsible for the eventual presence of clinical symptoms (Yetiser et al. 2002). In some occasions, pneumatized petrous apex cells can be fluid-filled. Such cells have an intermediate or high signal on the T1-weighted images and a high signal on the T2-weighted images. Trapped fluid is mostly confused with cholesterol granuloma, but the latter does not enhance except for a thin rim, while trapped fluid will often enhance moderately. The presence of trapped fluid in other mastoid cells often accompanies the fluid trapping in the apex (Fig. 3). CT is also able to ensure the radiologist that the petrous apex is opacified in a non-expansile way in case of fluid trapping.

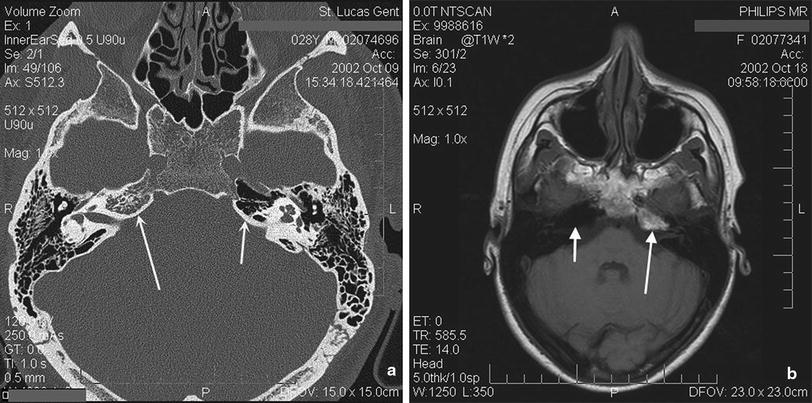

Fig. 3

Fluid trapping in pneumatized petrous apex cells show a high signal on the T2-weighted images (a) and are often accompanied by other mastoid cells that also contain trapped fluid (b)

2.2 True Petrous Apex Lesions

Petrous apex lesions have been classified in different ways by different authors. Where some divide the lesions in cystic and solid lesions, others distinguish destructive and non-destructive lesions. The two most frequent lesions in the petrous apex that need surgery are the cholesterol granuloma and cholesteatoma (Chang et al. 1998). Both are cystic and destructive/expansile lesions and account for respectively 60 and 9 % of all petrous apex lesions (Muckle et al. 1998). The differentiation between both is very important, because of their completely different therapeutic management. Cholesterol granuloma can be drained internally into the mastoid or middle ear, while cholesteatoma need a more aggressive removal, which often mandates the sacrifice of hearing (Chang et al. 1998; Profant and Steno 2000; Brackmann and Toh 2002). The experience of the surgeon is another important factor in the choice of the surgical approach (Haberkamp 1997).

2.2.1 Cholesterol Granuloma or Cyst

Cholesterol granuloma, also called cholesterol cyst or giant cholesterol cyst, is the most common primary lesion of the petrous apex, and accounts for 60 % of all lesions in that region (Muckle et al. 1998). They rarely occur bilaterally (Jaramillo and Winle-Taylor 2001). Cholesterol cysts contain a brownish liquid glistening with cholesterol crystals (Lo et al. 1984; Graham et al. 1985). Repetitive cycles of hemorrhage and granulomatous reaction—reason why such cysts are also referred to as granulomas—initiated by an obstruction of the ventilation outlet of the apex, are believed to cause cholesterol cysts (Nager and Vanderveen 1976).

Cholesterol cysts are most often seen in young adults and are treated surgically, by drainage of the petrous apex. The petrous apex can be achieved through different approaches, such as the transcanal infracochlear, transmastoid infralabyrinthine, middle fossa, translabyrinthine, and transotic ones. Determination of the best approach depends on the hearing status of the affected ear on the one hand, and the relationship between the petrous apex lesion and the surrounding neurovascular structures on the other hand. The translabyrinthine approach is useful in nonhearing ears, whereas the transcanal infracochlear approach with stenting is preferred in hearing individuals, if anatomy permits so (Brackmann and Toh 2002).

On MR, cholesterol cysts are hyperintense on both T1- and T2-weighted images (Fig. 4). Some have a hypointense rim on both T1- and T2-weighting (Greenberg et al. 1988). The contralateral apex is often pneumatized.

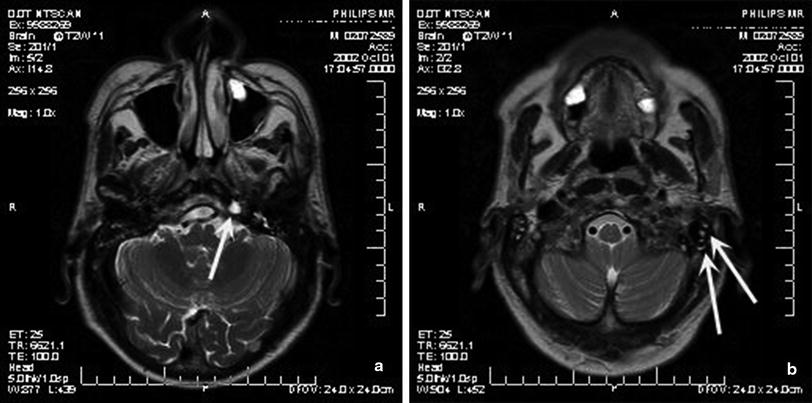

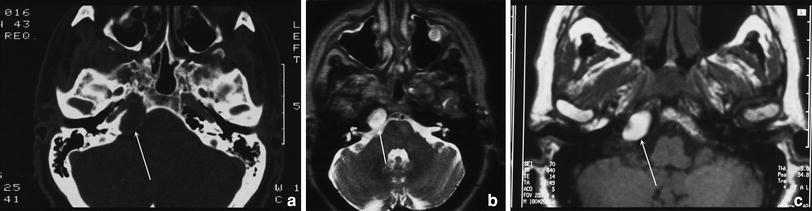

Fig. 4

Cholesterol cyst or cholesterol granuloma. CT (a) shows a round cystic lesion in the petrous apex on the right side. The finding is however aspecific. On MR, the well-defined mass is hyperintense on both the T2 (b)- and T1 (c)-weighted images. Note that the contralateral apex is partially pneumatized

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree