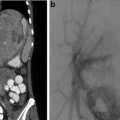

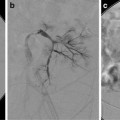

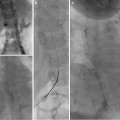

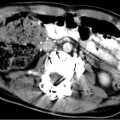

Fig. 8.1

A 16-year-old boy with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) presented with melena, abdominal pain, anemia (hemoglobin 7.9 g/dL, previously 11.5 g/dL), and tachycardia. He was admitted to the PICU and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed. No bleeding site was identified. After becoming hemodynamically unstable and requiring aggressive resuscitation, he was transferred urgently to the interventional suite. (a) Although visualization of GI bleeding usually requires selective catheterization and angiography, in this patient flush aortography demonstrated active intraluminal contrast extravasation (arrow) from a distal jejunal branch. (b) After selection of the SMA with a 4 F cobra catheter, coaxial microcatheter sub-selection confirmed active extravasation (arrow) and localized the culprit vessel. The microcatheter was advanced slightly more distally into the culprit vessel, and 500–700 μm polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particle embolization was performed. (c) Post-embolization SMA angiography shows cessation of active bleeding in the region of prior extravasation (dotted circle). The patient stabilized following embolization and had no episodes of rebleeding and no signs of bowel ischemia

Postprocedure Care

All patients should be watched for signs of rebleeding. The patient may still pass melanotic stools long after the bleeding has been stopped; therefore, stability of vital signs and hematocrit are more important to monitor. Any coagulopathy should also continue to be monitored and corrected. Although not reported in the literature, since femoral arterial access may be significantly more technically challenging and time-consuming in small children than in adults, if the initial diagnostic arteriography is negative, one may consider leaving the femoral arterial sheath in place for a short time (<24 h) in order to expedite any additional arteriography for recurrent bleeding. Of course, the risk of complications from extended femoral artery catheterization, including femoral artery thrombosis, should be considered.

For patients who have received vasopressin therapy, once an initial dose rate has been established and control of bleeding has been confirmed, the dose rate should be tapered over 24–48 h. After vasopressin has been tapered, normal saline should be infused for an additional 6–12 h, so that if bleeding recurs, the catheter is still in place and vasopressin can be restarted. The patient must remain in the ICU during vasopressin infusion with careful monitoring for antidiuretic or cardiovascular side effects.

Chapter Summary

Background

Etiology

Liver: trauma, transplantation

Gut:

∘ Gastritis/espophagitis

∘ Esophageal varices (portal hypertension)

∘ Mallory-Weiss tear

∘ Gastrostomy tubes

∘ Eosinophilic gastroenteropathy

∘ Infectious diarrhea

∘ Anal fissure

∘ Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia

∘ Inflammatory bowel disease

∘ Henoch-Schonlein purpura

∘ Meckel’s diverticulum

∘ Typhlitis (neutropenic patients)

Indications and Contraindications

No response to conservative management

Continued blood requirements (>500 mL in adult sized patients)

Endoscopy failed, inconclusive or unavailable

No absolute contraindications

Pre-procedure Evaluation

Coagulation and hemoglobin optimized as possible

Blood products in room

Workup as for other forms of angiography

Equipment

4/5 F vascular sheath

Selection of angiographic catheters

Cobra

Sos Omni

Simmons

RIM

Microcatheters

Procedure Technique

Diagnostic arteriography

Intervention

Embolization

∘ Particles

∘ Microcoils

∘ Glue

Drugs

∘ Vasopressin

Post-procedure Care

Wean vasopressin

Monitor for signs of recurrent bleeding

References

1.

Arain Z, Rossi TM. Gastrointestinal bleeding in children: an overview of conditions requiring nonoperative management. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1999;8(4):172–80.PubMed

2.

Meyerovitz MF, Fellows KE. Angiography in gastrointestinal bleeding in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143(4):837–40.PubMed

3.

Whitaker SC, Gregson RH. The role of angiography in the investigation of acute or chronic gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Clin Radiol. 1993;47(6):382–8.PubMed

4.

Rollins ES, et al. Angiography is useful in detecting the source of chronic gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(2):385–8.PubMed