Clinical severity assessment

Mild

Severe

Infants

Temperature <38.5 °C, respiratory rate <50 per min, mild recession, taking full feeds

Temperature >38.5 °C, respiratory rate >70 per min, moderate/severe recession, unable to feed

Older children

Temperature <38.5 °C, respiratory rate <50 per min, mild breathlessness, no vomiting

Temperature >38.5 °C, respiratory rate >50 per min, severe difficulty breathing, nasal flaring, cyanosis, grunting respiration, dehydration

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications for percutaneous small-bore pigtail drain insertion. While coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia are important clinical concerns, they are uncommon and most children can be adequately improved by transfusion of appropriate blood products so that a relatively low-risk procedure such as image-guided small-bore catheter placement is safe and feasible.

The presence of a hydropneumothorax on the preprocedural imaging should raise the possibility of underlying parenchymal necrosis or abscess formation and a greater risk for protracted chest drainage due to the presence of a bronchopleural fistula. While these findings are not a contraindication to drain insertion, the requirement for protracted chest drainage in these clinical circumstances needs to be clearly discussed with the referring service and the child’s parents prior to embarking on the procedure.

Preprocedural Workup

Laboratory Workup

Children presenting with symptoms severe enough to warrant referral to a pediatric interventional radiology service will usually already have undergone prior laboratory investigations. In most cases, a complete blood count, differential, and routine blood biochemistry should be available. Almost all cases show a leukocytosis as the principal abnormal finding. Thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are uncommon in this patient population. Most practitioners would not advocate that a coagulation profile be performed routinely on all children, as the diagnostic yield in otherwise healthy children who are not on anticoagulation therapy is extremely limited and poorly cost efficient.

Imaging Workup

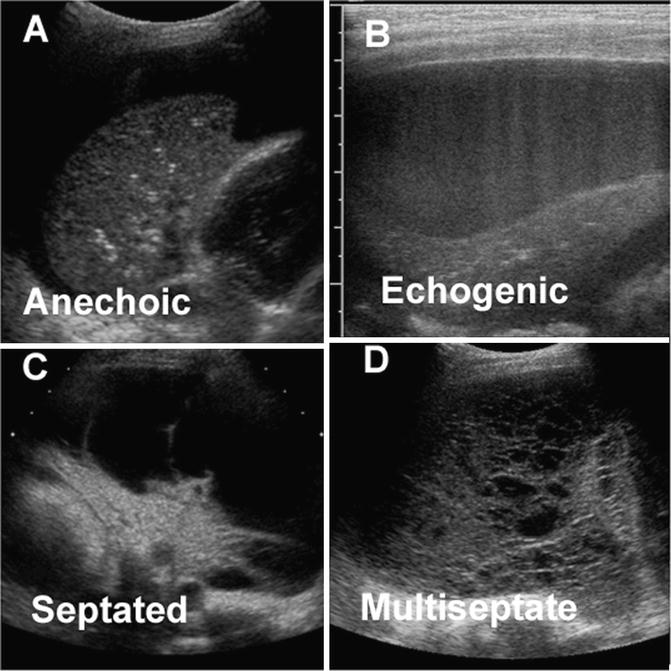

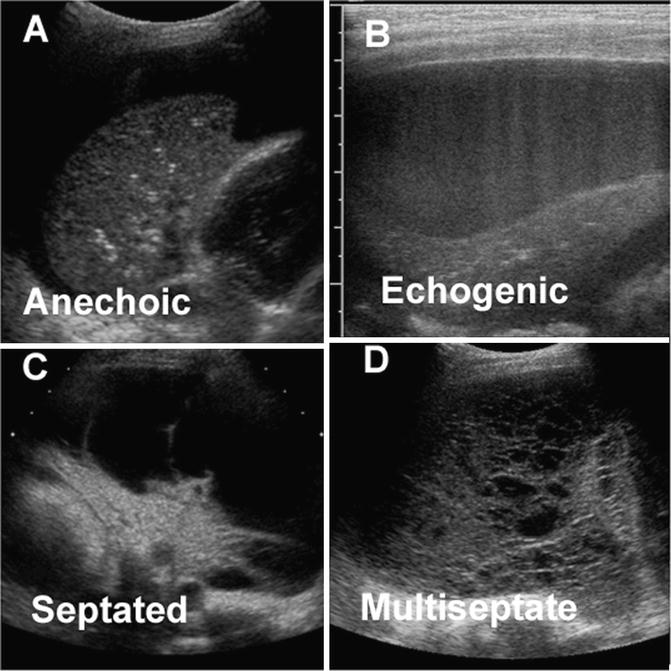

There is limited published evidence regarding the appropriate imaging pathway to choose in investigation of pediatric empyema [9]. A frontal chest radiograph is the optimal initial imaging test (Fig. 19.1). There is no role for a routine lateral chest radiograph. While the radiology literature historically describes decubitus films as a useful test to define whether a pleural collection is free or loculated, it involves ionizing radiation and requires additional radiographs in an ill and often uncooperative child. The most useful imaging investigation is chest ultrasound as it can confirm the presence of pleural fluid and assess the nature of the fluid. Ultrasound also has additional benefits in that it is easily portable, does not involve use of ionizing radiation, and allows a dynamic view of the lung and pleural space. Ultrasound allows visualization of the nature of the collection to see if the fluid is anechoic, echogenic, septated, or a complex organizing pleural collection and to assess for the presence of a pleural peel (Fig. 19.2). The evidence regarding the ability of ultrasound to predict the success of pleural drainage is mixed, with some papers suggesting that the grade of the pleural collection allows prediction of success of the intervention and length of stay [10, 11], while others have found no such link [12]. The anecdotal experience of many interventional radiologists suggests that as pleural collections become more septated over time, the probability that small-bore catheter insertion alone will have a low probability of treatment success without the addition of fibrinolytics.

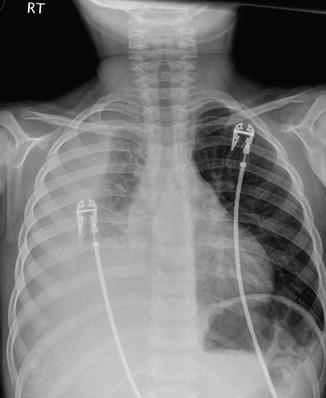

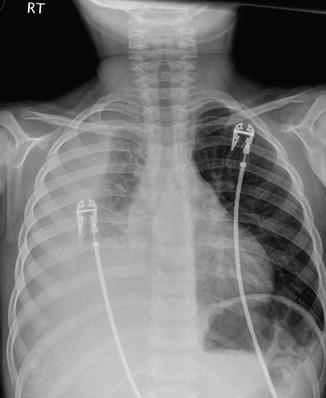

Fig. 19.1

Frontal chest radiograph of a 22-month-old child with a fever and tachypnea revealing a right middle and lower lobe pneumonia and a lentiform extrapulmonary parapneumonic effusion

Fig. 19.2

A spectrum of the findings seen during chest ultrasonography in pediatric empyema. (a) Sonographic image of an anechoic pleural collection. (b) Sonographic image of an echogenic pleural collection. (c) Sonographic image of a septate pleural collection. (d) Sonographic image of a multiseptate “honeycomb” pleural collection

CT has a limited role in imaging children with empyema. While CT defines more parenchymal abnormalities than chest radiographs, this rarely alters management. CT is unable to predict clinical outcome, may require an anesthetic, and requires exposure to ionizing radiation [12]. CT should be reserved as a problem-solving tool for a child who has complicated parenchymal disease and who remains febrile and unwell despite an adequately placed drainage catheter. CT is often requested by thoracic surgeons prior to embarking on VATS or decortication. The BTS guidelines acknowledge this fact although this approach is not supported by any systematic studies [4].

Equipment

A list of equipment required for the procedure is listed in Table 19.2.

Table 19.2

Equipment

• Sterile skin preparation and drapes |

• Local anesthesia, syringes, and needles |

• Sterile probe cover |

• 8-MHz curvilinear probe (footprint fits in rib space for interventions) |

• Access to fluoroscopy during the procedure is helpful but not vital |

• 21-gauge “micropuncture” access for children under 10 kg (6 months) |

• Access needle (16-gauge IV cannula, 19-G needle) for all other children |

• 0.035-in. standard floppy guidewire for children under 6 months |

• 0.035-in. stiff guidewire for older or obese children |

• Number 11 scalpel blade |

• Over the wire dilators sized appropriately for the drain to be inserted |

• <20 kg 8.5-French pigtail-type locking catheter |

• >20 kg 10–14-French pigtail-type locking catheter |

• Sterile sample containers for microbiological analysis |

• Underwater seal system and access to low-pressure suction |

• Clear dressing for pigtail site (allows chest U/S follow-up) |

• Tape/dressings for securing heavy underwater seal drainage tube |

Procedure Technique

Anesthesia

Children with compromised respiratory function due to their empyema may not be fit for general anesthesia, although at most institutions, controlled sedation under the supervision of anesthesiologist or staff appropriately trained in administering sedation to ill children is often adequate to allow drain placement.

Patient Positioning

Most pleural drainage procedures can be performed with the child in a supine position. Occasionally, it may be necessary to position a child on its side or partially rolled forward to access a specific location within the pleural space that has been identified on the preprocedural imaging.

Aseptic Preparation

Full aseptic procedures should be employed when inserting a drainage catheter into the pleural space. This includes a formal surgical scrub prior to gowning, gloving up for the procedure, and placing a sterile probe cover over the chosen ultrasound probe. The most common skin preparation agents used today include products containing iodophors or chlorhexidine gluconate. There is increasing evidence that skin preparation with alcohol-based chlorhexidine preparations is associated with reduced risk of surgical or drain site infection [13, 14]. If alcohol-based skin preparations are used, then appropriate time needs to elapse to allow the alcohol to evaporate prior to draping. Care needs to be taken not to allow excess pooling of skin preparation agents behind the child as this can make the child cold and may result in skin injury or breakdown [15].

Image Guidance

Image-guided needle placement is advocated even in cases where a very large pleural collection is present. A curvilinear probe is adequate to allow visualization for almost all chest drain insertions from neonates to larger teenagers as this probe has a small footprint to facilitate easy access to the puncture site. Most experienced interventional radiologists would advise taking a few moments at the beginning of the procedure before a child is sedated for the operator to evaluate the pleural space for themselves as this may save the need to resite or replace a badly positioned drainage catheter later.

Drainage Catheter Insertion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree