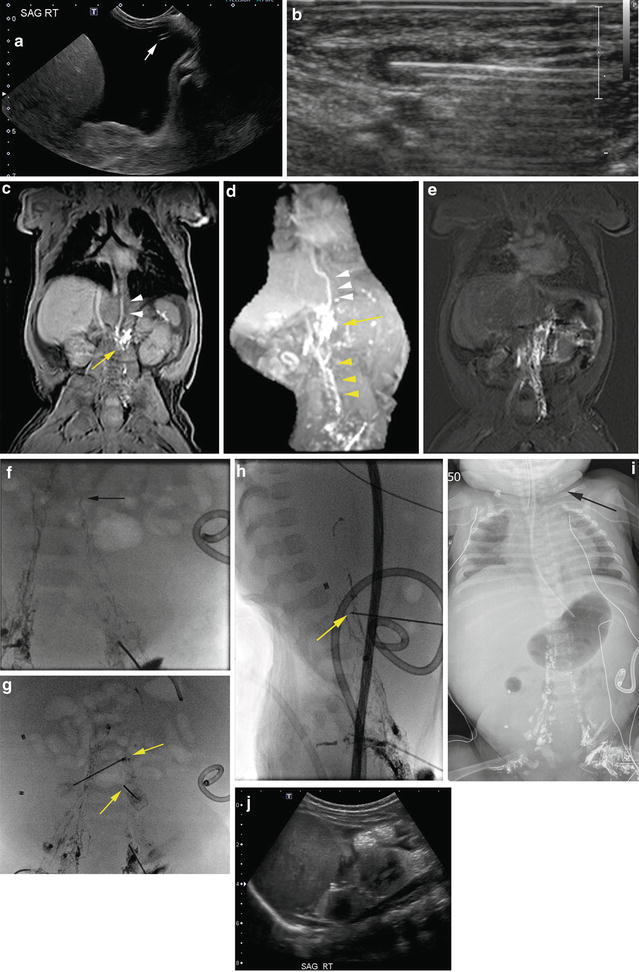

Fig. 16.1

Cisterna chyli. A linear collection of oily contrast drops opacifies the cisterna chyli overlying the L2 vertebral body

Small lymphatic-venous connections are normally present but are not visualized unless an obstruction is present (Fig. 16.2) [13–15].

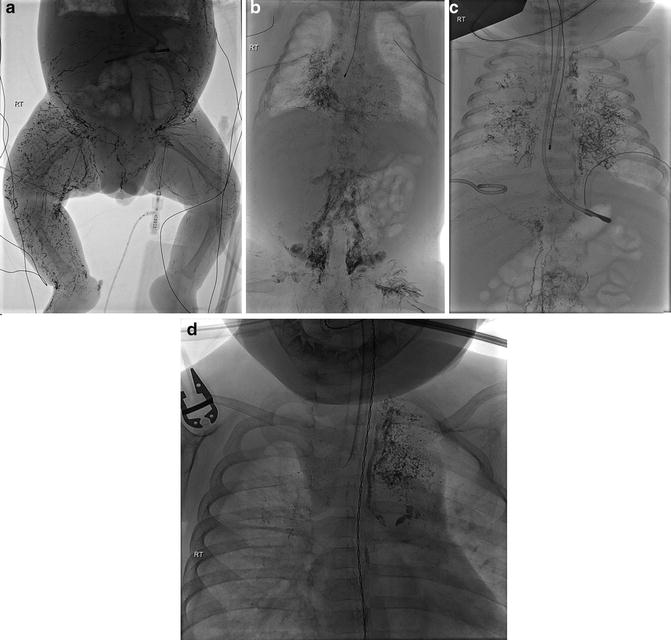

Fig. 16.2

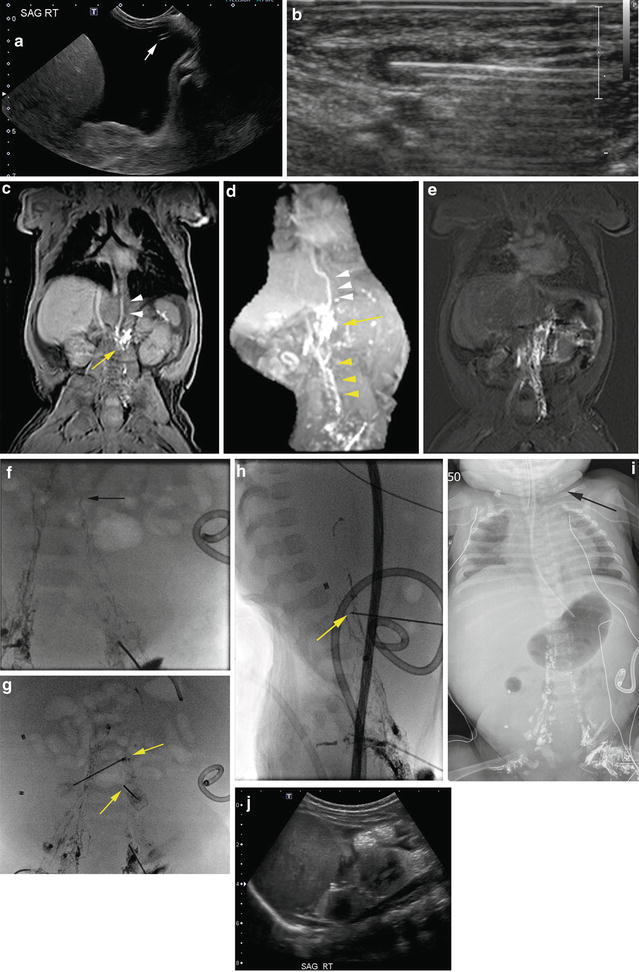

Lymphatic disruption to treat congenital chyloperitoneum. (a) Ultrasound (US) shows large-volume fluid collection. Fetal urinary drain placed to decompress chyloperitoneum in utero became displaced into the abdomen (white arrow). (b) US used to insert a 22-G Angiocath into the groin lymph node. (c) FLASH and (d) MIP MR images showing dilated lumbar collaterals (yellow arrowheads) perirenal lymphatic leak (yellow arrow) and opacification of the azygous vein through lymphovenous channels (white arrowheads). (e) Delayed FLASH image shows accumulation of peritoneal contrast and “staining” of the perilymphatic tissues. (f) Fluoroscopic freeze frame image showing location of leaking lymphatic vessel. Note “chaser” technique used to access pelvic node. (g) AP and (h) lateral images show 22-G needles used to disrupt the leaking duct. (i) Chest radiography performed 48 h after lymphangiogram shows passage of Lipiodol to jugular lymph nodes (black arrow). (j) US image 4 months after procedure shows near complete resolution of ascites

Indications/Contraindications

Lymphangiography is performed for both diagnostic and interventional purposes. The most common indication for intervention is chylothorax following cardiac surgery that is not controlled by conservative measures and/or after failed surgical thoracic duct ligation. There are many diagnostic indications including characterization of lymphatic abnormalities or determination of the location of thoracic, abdominal, or pelvic lymphatic leaks (Figs. 16.2c–f, 16.3, and 16.4a). There are numerous reports of cessation of lymphatic drainage following diagnostic lymphangiography with oil-based contrast [16–18].

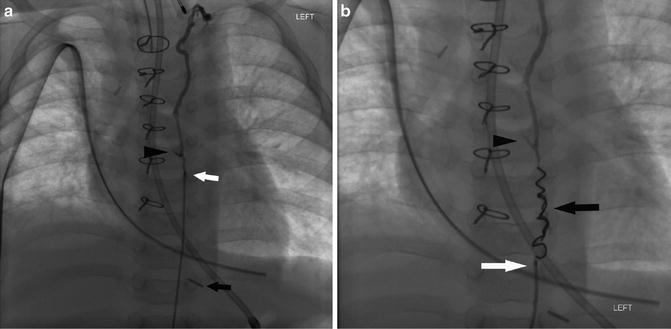

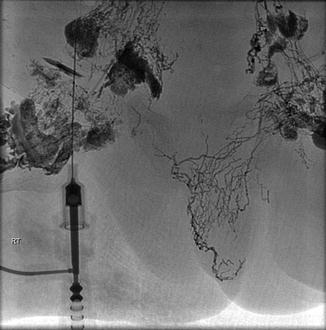

Fig. 16.3

Lymphatic ectasia. (a, b) Lipiodol injection demonstrates abnormal lymphatic flow down the legs and around the abdominal wall in patient with severe lymphatic ectasia and absence of central lymphatic ducts. (c) Congenital lymphatic ectasia with abnormal retroperitoneal and bronchial lymph channels. (d) Congenital ectasia with peribronchial channels that were the cause of chylothorax

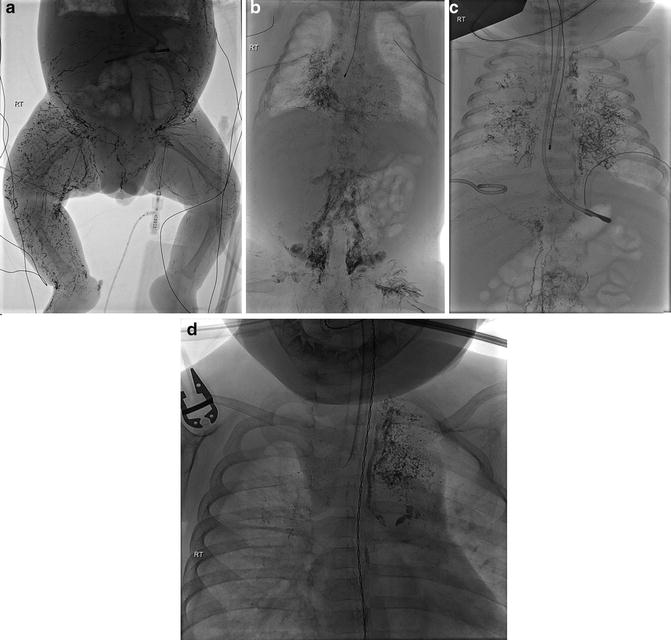

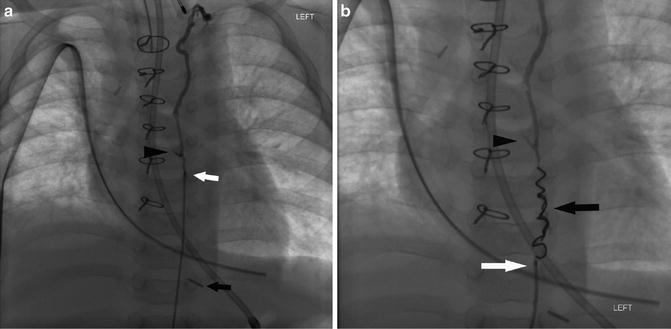

Fig. 16.4

Thoracic duct embolization with coil. (a) The thoracic duct was opacified using a microcatheter (white arrow) delineating a pericardial lymphatic leak (black arrowhead). Note the site of previously attempted surgical ligation (black arrow). (b) A coil was deployed in the thoracic duct (black arrow)

Other than uncorrectable coagulopathy, there are no specific contraindications to performing lymphangiography. However, use of oily contrast is absolutely contraindicated in patients with an active right-to-left cardiac shunt due to the risk of arterial embolization. Water-soluble contrast should be used in any patient with an intracardiac shunt. However, in unusual cases, oil-based contrast could be considered in patients who have only a potential shunt (e.g., patent foramen ovale with no active shunting detected), but the possibility of arterial embolization must be discussed with the patient. Oil-based contrast can cause pneumonitis [19, 20] so caution must be exercised in patients with limited respiratory reserve. Patients with impaired renal function are not candidates for MR lymphangiogram study with gadolinium injection.

Equipment

For intranodal injection in the groin:

25-G-long needle, short connecting tube, 5 mL syringe

For pedal access:

Surgical microscope/magnifying surgical loupes, methylene blue, local anesthetic, scalpel, and surgical dissection equipment

30-G Cook Lymphangiography needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA)

Local anesthetic

Contrast media:

For embolization:

22-G-long Chiba needle (tip is bent slightly for easy maneuverability)

Sturdy wire with floppy tip (0.018″ V-18 ControlWire guidewire, Boston Scientific, Natick, USA)

High-flow 2.3F short-length microcatheter—(65 cm 2.3F Rapid Transit, Boston Scientific, Natick, USA)

Various embolization coils, cyanoacrylate glue, tantalum powder

Pre-procedure Workup

No specific blood work is necessary although complete blood count (CBC) with group and hold can be considered.

Procedure Technique

General anesthesia is required for both diagnostic and interventional components of the procedure. When intervention is undertaken, wide-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis to cover for potential bowel transgression is recommended [22]. Dynamic MR lymphangiography is becoming increasingly utilized for lymphatic leak localization and characterization [21, 23].

The diagnostic procedure can be performed either by direct intranodal injection or pedal lymphatic duct cannulation. Intranodal injection of contrast is the preferred technique as it has many advantages over the pedal cannulation technique. Intranodal injection is easier to perform, less time-consuming, and hence less radiation exposure to the child. Better contrast opacification of the thoracic duct can be obtained by accessing multiple nodes in the groin region and by accessing nodes bilaterally. Pedal duct cannulation requires a high level of skill and training to access the tiny lymph vessel, and success rates are not high. Accessing the lymphatic vessels in both pedal regions can be very time-consuming and takes a long time for the contrast to flow from the pedal region to the thoracic duct region. The technique of pedal duct cannulation is still important, as it is the only method to demonstrate lymphatic leaks in the groin region following multiple groin punctures related to vascular access for cardiac catheterizations and interventions (Fig. 16.5).

Fig. 16.5

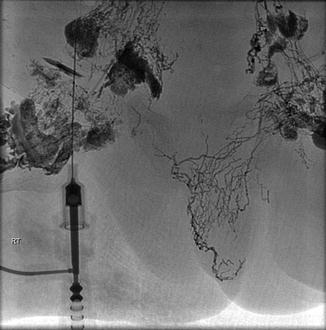

Lymphatic leak following cardiac catheterization. Pedal access is required to perform lymphangiography when a lymphatic leak is suspected in the groin area

The diagnostic lymphangiogram by intranodal injection can be performed using either MRI or fluoroscopy. At the current time, MR lymphangiogram with intranodal injection of dilute gadolinium is becoming the method of choice for diagnostic assessment [21]. In many cases, MR lymphangiography provides additional information regarding the cause of lymphatic leaks without exposure to ionizing radiation (Figs. 16.2c–e and 16.6).

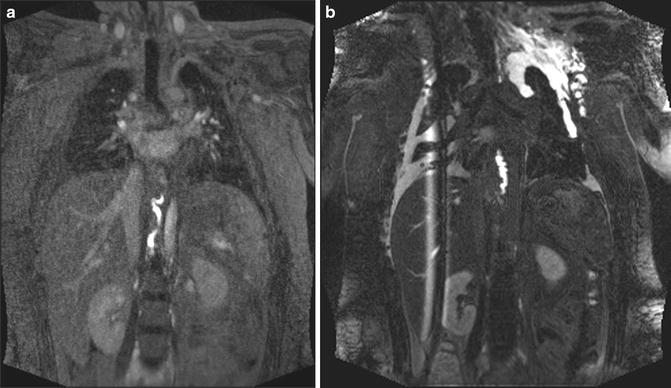

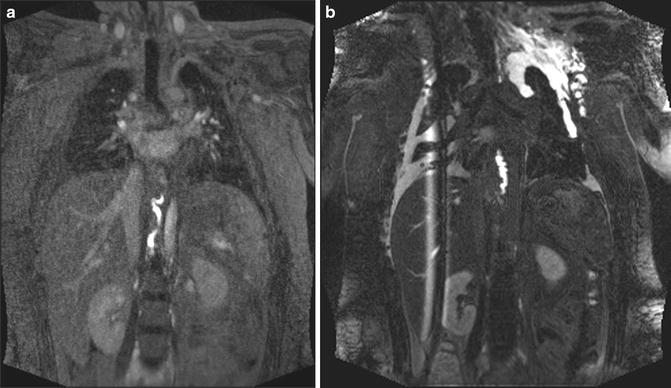

Fig. 16.6

MR lymphangiogram. (a) Early and (b) delayed FLASH MR images were obtained. The delayed image shows the contrast leak and accumulation within the left pleural space

Diagnostic Lymphangiogram with Intranodal Access

A high-frequency linear probe is used to introduce the tip of a small (21–25 G) needle or angiocatheter into the medulla of a lymph node in the inguinal area (Fig. 16.2b). A small test injection with saline can help to demonstrate that the needle tip is in an appropriate position and there is no extravasation. Contrast must be injected slowly to assure that you do not “blow” the node allowing contrast to leak into the surrounding tissues. Injection rates of oil-based contrast around 0.1–0.2 mL/min are described in adult patients [17, 18, 24]. Reported injection volumes of oil-based contrast range from 0.3 to 0.5 mL in infants [7], 1–6 in children [25], and 1–8 mL (with a maximum of 14 mL) in adults [25].

For MR lymphangiography, the angiocatheter is stabilized using a clear dressing and the patient is moved to the MRI machine. Coronal thin section volumetric T1-weighted FLASH sequence images are obtained at regular intervals during the contrast injection (Figs. 16.2c and 16.6a). Delayed images are also obtained which better demonstrate the leak and accumulation of contrast in the serous cavities if present (Figs. 16.2e and 16.6b).

If extravasation occurs during nodal injection under fluoroscopy or if the contrast is not sufficient to opacify the thoracic dust/cisterna chyli, a node “chaser technique” is used wherein a higher node in the chain along the iliac vessels can be accessed either by ultrasound or fluoroscopy (Figs. 16.2g, h and 16.7). Since a thin-bore 25-G needle is used, the risk of vascular injury is minimal when a pelvic node is accessed.

Fig. 16.7

“Chaser” technique. A 25-G needle has been inserted into a left iliac chain node to promote opacification of the lymphatic chain

Pedal Duct Cannulation

To facilitate visualization of a lymphatic duct prior to cannulation, methylene blue is injected in the web spaces between the toes. When a duct has been identified on the dorsum of the foot, local anesthetic is injected, and a transverse incision is made in the overlying skin. Blunt dissection is used to gently free the duct. A surgical microscope or loupes can be helpful to help cannulate the duct with a 30-G lymphangiography catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, USA). When successfully accessed, a suture is drawn around the needle to help it fix in place during contrast injection.

Thoracic Duct Embolization

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree