Jean Noel Buy1 and Michel Ghossain2

(1)

Service Radiologie, Hopital Hotel-Dieu, Paris, France

(2)

Department of Radiology, Hotel Dieu de France, Beirut, Lebanon

22.1 Atrophy

22.1.1 Definition

22.1.2 Etiology

22.1.3 Clinical Findings

22.1.4 Ultrasound

22.2 Polyps

22.2.1 Generalities

22.2.2 Imaging Findings

22.3.1 Generalities

22.3.2 Imaging Findings

22.4.1 Endometrial Carcinoma

22.4.3 Miscellaneous

22.5 Endometritis

22.6 Effects of Therapy

22.6.1 Drugs

22.6.3 IUD

22.6.4 Radiation

Abstract

Glands are lined by a single layer of flattened or cuboidal epithelial cells containing bland nuclei without mitoses. Mucus is scant. Glands may be fragmented.

22.1 Atrophy

22.1.1 Definition

22.1.1.1 Microscopy

Glands are lined by a single layer of flattened or cuboidal epithelial cells containing bland nuclei without mitoses. Mucus is scant. Glands may be fragmented.

Stroma is markedly reduced.

22.1.1.2 Macroscopy

The endometrium is thin (0.5 mm for one layer). The glands are often cystic [1].

22.1.2 Etiology

Atrophy is related to insufficient estrogen stimulation in:

1.

In premenopausal women

Women taking oral contraceptives

Drugs:

Oral contraceptive

GnRH agonists

Progestin

Premature ovarian failure

Radiation

Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea

2.

In postmenopausal women without hormonal treatment

22.1.3 Clinical Findings

In premenopausal women, atrophy of the endometrium may be responsible of amenorrhea or vaginal bleeding.

22.1.4 Ultrasound

The endometrium is thin (Fig. 22.2). Cystic spaces may be present.

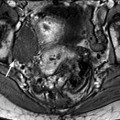

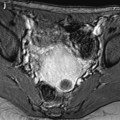

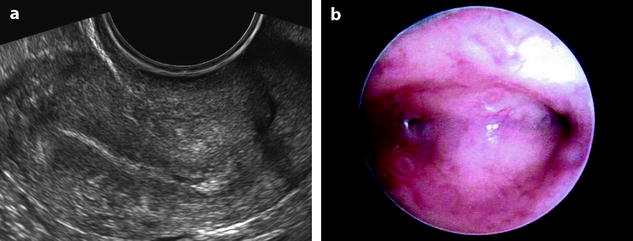

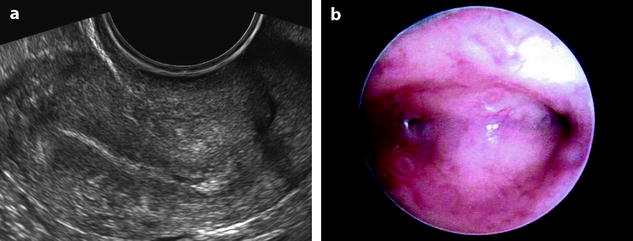

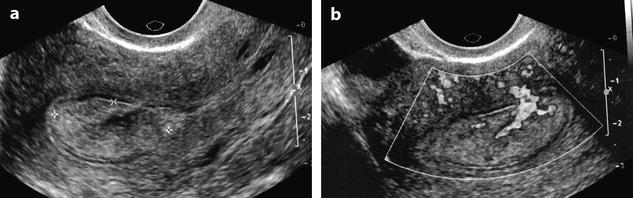

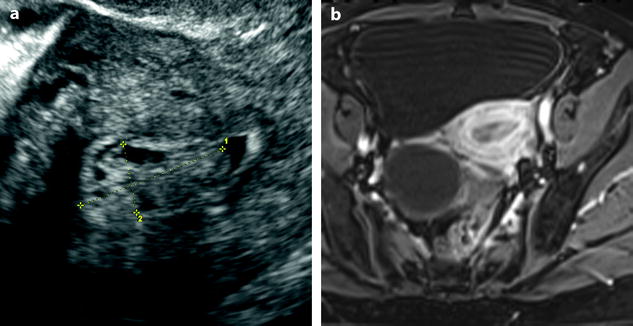

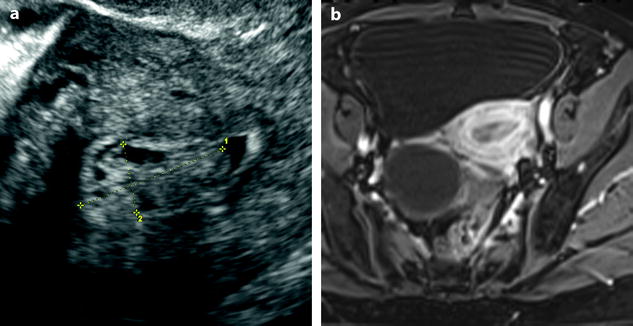

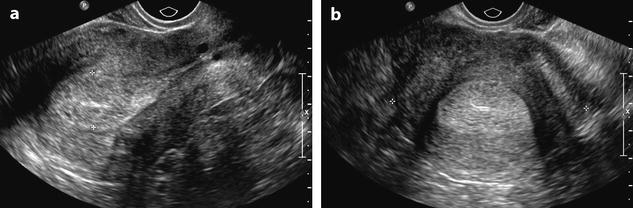

Fig. 22.2

Atrophy of the endometrium. Thirty-eight-year-old woman. Secondary amenorrhea with a low anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) related to premature ovarian failure. Longitudinal EVS (a) displays a thin endometrium, related to atrophy. Because of a desire of pregnancy, a hysteroscopy is performed. Hysteroscopy (b) confirms a marked atrophy with a pale mucosa

22.2 Polyps

22.2.1 Generalities

22.2.1.1 Definition

Endometrial polyps are benign localized overgrowths of endometrial glands and stroma that are covered by epithelium and project above the adjacent surface epithelium.

22.2.1.2 Pathology

Macroscopic and Radiologic Findings

They are reported in Table 22.1 [4] (Fig. 22.3).

Table 22.1

Macroscopic and radiologic findings of endometrial polyps

–Broad base or pedunculated or attached to the endometrium by a slender stalk |

–May contain small cystic spaces |

–Size: from 1 mm to a large mass filling the entire cavity |

–Site: anywhere in the uterine cavity but most common in the fundus |

–Surface: glistening or hemorrhagic |

–Multiple in 20 % of cases |

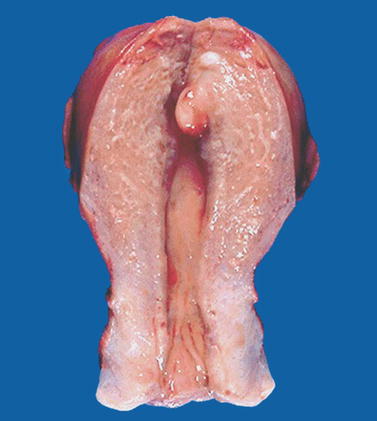

Fig. 22.3

Endometrial polyp. Macroscopic view of the uterine cavity shows a well-delineated pedunculated polyp of the fundus

Microscopy

Stroma

May contain endometrial stroma, fibrous tissue, or smooth muscle, but generally the stroma appears more fibrous than normal fundic endometrium.

Vessels

Thick-walled vessels are seen at the base.

Epithelium and Glands

Secretory changes in the endometrial glands may be weak or absent, or the glands may appear dilated and inactive. Most are categorized as hyperplastic, functional, or atrophic.

Hyperplastic polyps contain proliferating irregularly shaped glands resembling diffuse hyperplasia.

Atrophic polyps consist of low columnar or cuboidal cells lining cystic dilated glands; they are typically found in postmenopausal women (Fig. 22.4).

Fig. 22.4

Endometrial polyp with cystic atrophy. Histology of a polyp in a menopausal woman displays: an atrophic endometrium (lower oblique arrow) with a thin epithelium and cystic glands (upper oblique arrow). Small polyp (asterisk) with cystic atrophy. Adjacent leiomyoma (M)

Functional polyps containing glands resembling normal cycling endometrium are relatively uncommon.

Hyperplasia, carcinoma (any type), and carcinosarcoma may involve or be entirely confined to a polyp [4].

22.2.1.3 Clinical Findings

It is common in women over 40 years.

During reproductive age years, the most common presentations are metrorrhagia or menometrorrhagia. It may be a cause of infertility.

After menopause, postmenopausal bleeding is the common finding.

A polyp should always been considered after curettage (if not associate to hysteroscopy), because polyps that contain a delicate stalk may elude the curette.

22.2.2 Imaging Findings

22.2.2.1 Ultrasound

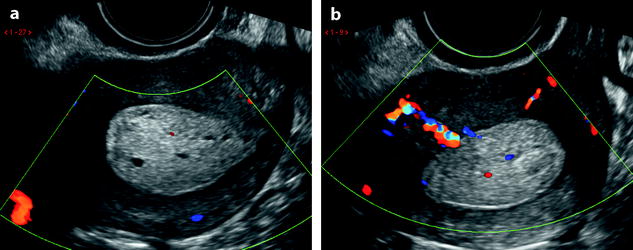

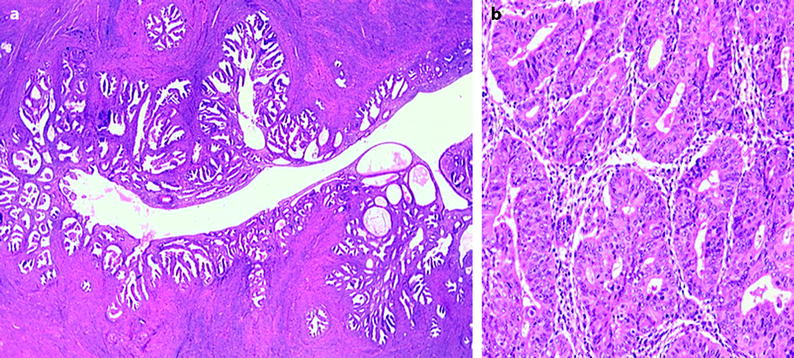

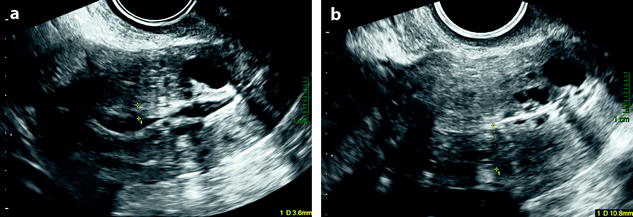

Endovaginal US with eventually hysterosonography is the best method to detect small polyps that can be missed or misdiagnosed with MR. Endometrial polyp usually appears as a round or elongated mass. In premenopausal woman, it is usually well depicted during the first part of the endometrial cycle. Indeed, at this phase, the polyp, which echogenicity is high and identical to the basalis layer of the endometrium, is clearly distinguished from the low echogenicity of the functionalis layer of the endometrium. On the opposite, an endometrial polyp can be difficult to visualize during the second part of the cycle because the deep and superficial layers of the endometrium and the polyp have the same echogenicity. In some cases, it is covered by a thin layer of superficial endometrium (Fig. 22.5).

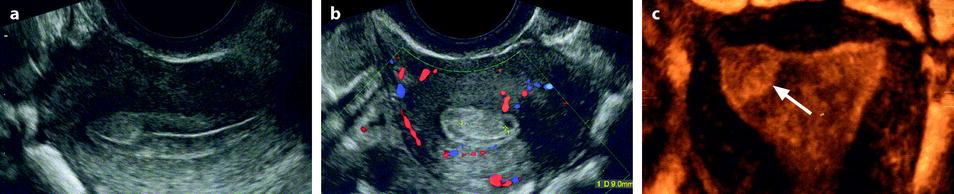

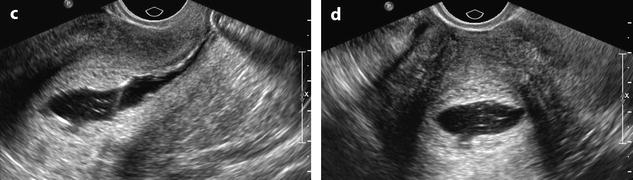

Fig. 22.5

Endometrial polyp in a 39-year-old woman with menometrorrhagia. (a, b) Sagittal (a) and transverse (b) endovaginal ultrasound during the first part of the menstrual cycle discloses a 9 mm hyperechoic polyp (cursors) of the anterior endometrium with no vascular pedicle on color Doppler. The hyperechoic polyp is in contact with the basal endometrium and covered by a normal hypoechoic superficial endometrium. Some liquid is present in the endometrial cavity. (c) Hyteroscopy confirmed the presence of an anterior polyp (arrow)

In some cases, endometrial polyp can appear only as an endometrial thickening (Fig. 22.6) mainly when associated to a premenopausal or postmenopausal atrophic endometrium. In these difficult cases, a vascular pedicle or hysterosonography may be very useful to diagnose them.

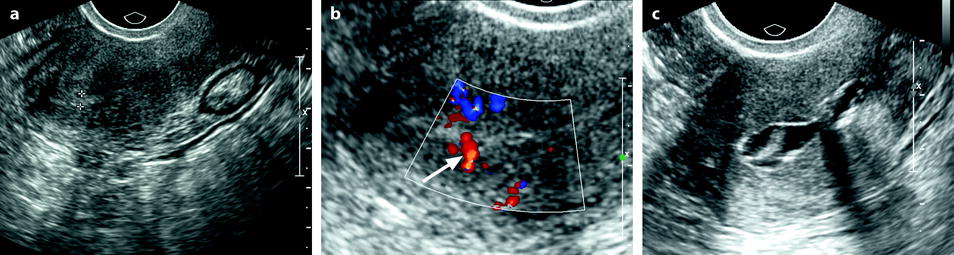

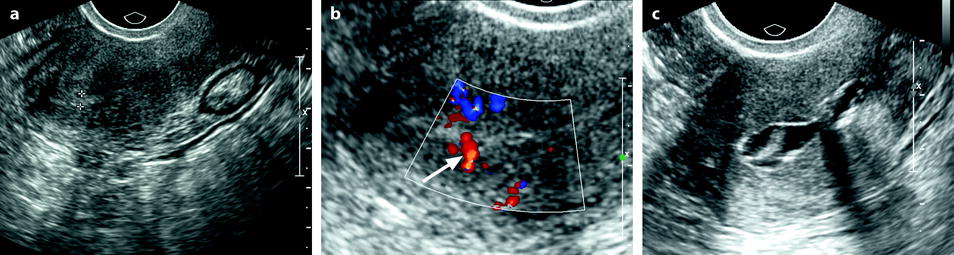

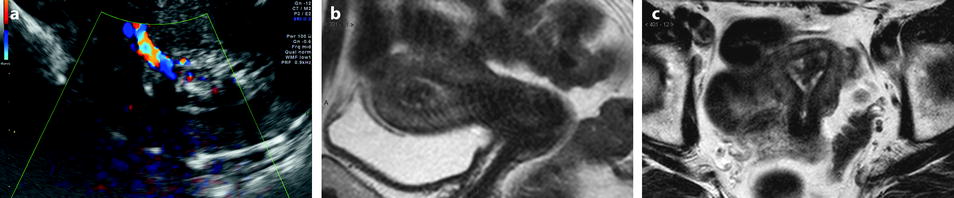

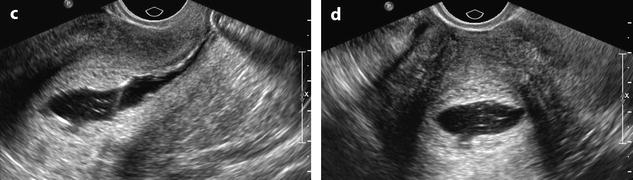

Fig. 22.6

Endometrial polyp appearing as a localized endometrial thickening. Forty-year-old woman with menometrorrhagia. (a) EVS, very early in the menstrual cycle, displays a thin endometrium in the lower part of the corpus and a localized thickening (cursors) of about 3 mm in the fundus. (b) Doppler demonstrates a posterior pedicle (arrow) entering the endometrial thickening, very suggestive of an endometrial polyp. (c) Hysterosonography definitely confirms the diagnosis of an endometrial polyp

The morphologic and vascular findings are reported in Table 22.2 (Figs. 22.7 and 22.8).

Table 22.2

Morphologic and Doppler findings of endometrial polyps

–Round or elongated echogenic mass; sometime localized thickening of the endometrium |

–Hyperechoic; may contain cystic spaces |

–Regular limit; sometimes peripheral hyperechoic line |

–Narrow or broad base attachment |

–Vascular pedicle |

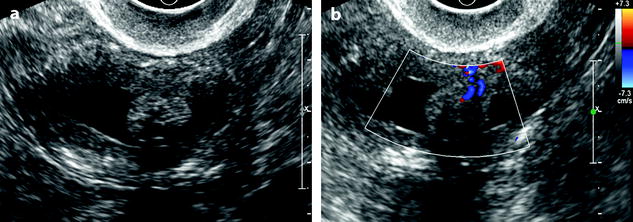

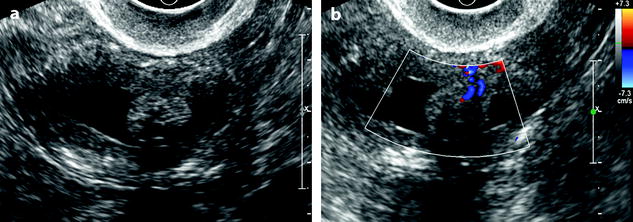

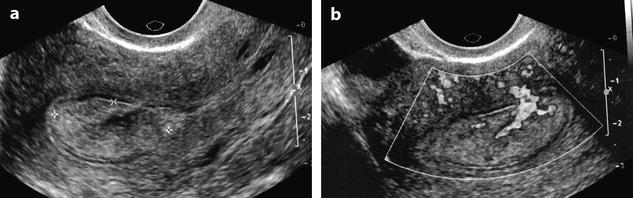

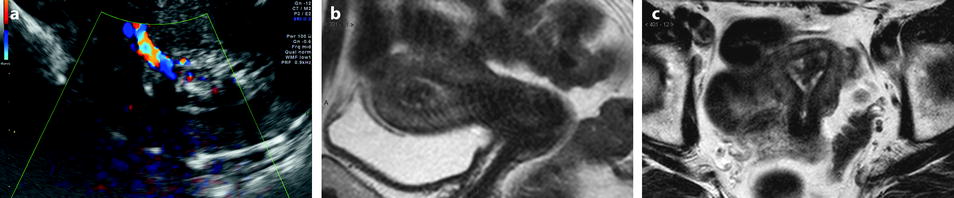

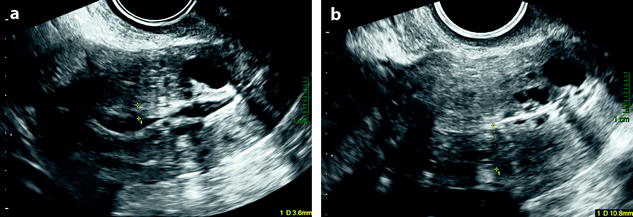

Fig. 22.7

Endometrial polyp. Seventy-nine-year-old woman with genital prolapse. EVS (a), transverse view, displays a mass protruding into the endometrial cavity, well delineated by hydrometria. Its echogenicity superior to myometrium and cystic spaces contained within the mass are very suggestive of an endometrial polyp. Doppler (b), longitudinal view, demonstrates an anterior vascular pedicle typical for an endometrial polyp

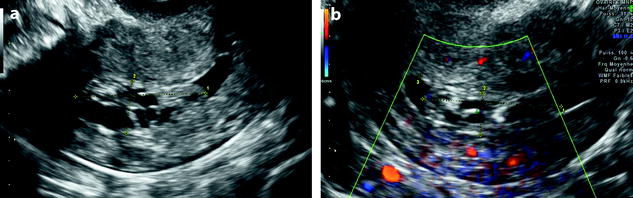

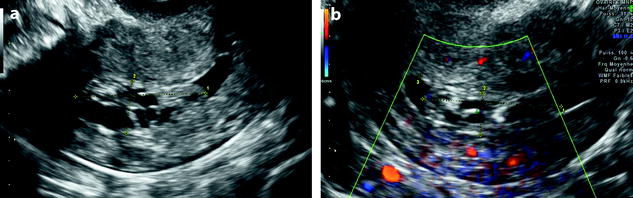

Fig. 22.8

Endometrial polyp. Forty-year-old woman with menometrorrhagia. EVS (a) displays a 2.5-cm elongated mass protruding in the endometrial cavity with a smooth regular limit. The mass is echogenic containing multiple cystic spaces with regular limits typical for an endometrial polyp. Doppler (b) does not display any pedicle or any vessel in the polyp

Cystic spaces: Small cystic spaces usually from 2–3 mm in diameter, with a regular border typically surrounded with a hyperechoic line, when present are typical for a benign polyp. Cystic spaces have also been reported in some cases of carcinomas, although they are much more uncommon [5] and do not have the same morphologic features, i.e., are not as regular and particularly are not surrounded by a hyperechoic line.

2D [6] and 3D hysterosalpingo sonography [7] have been demonstrated valuable in the diagnosis of endometrial polyps and particularly to demonstrate the pedicle and the peripheral hyperechoic line.

Hyperechoic line: A peripheral hyperechoic line has been demonstrated as a valuable finding of focal process (polyp or submucous leiomyoma) (Fig. 22.9). This finding is usually not present in endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma.

Fig. 22.9

Endometrial polyp in a 58-year-old postmenopausal woman with metrorrhagia. (a) Sagittal endovaginal ultrasound discloses a hyperechoic endometrial polyp (cursors). A thin layer of anechoic liquid separates the hyperechoic line corresponding to the atrophic endometrium from the hyperechoic line covering the polyp. (b) Color Doppler clearly displays a vascular pedicle. Hysterectomy confirmed the presence of a fibro-glandular not-proliferative polyp

Vascular pedicle: Visualization of a central vascular pedicle usually with a single regular vessel is a fundamental finding of a polyp (Fig. 22.10).

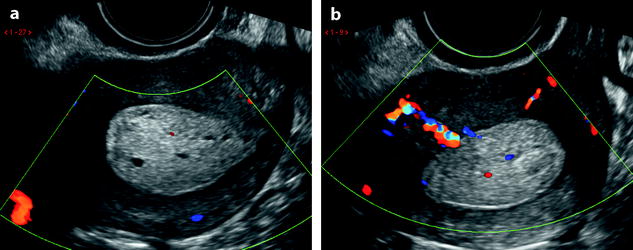

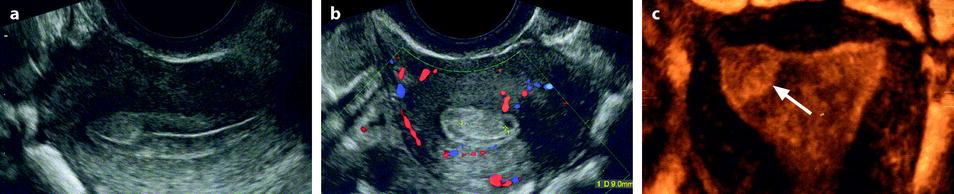

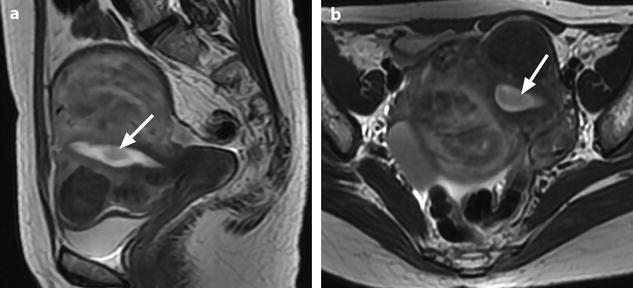

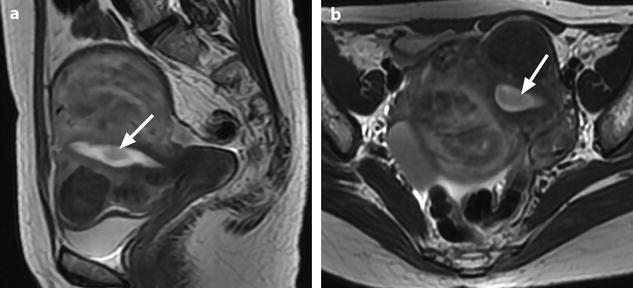

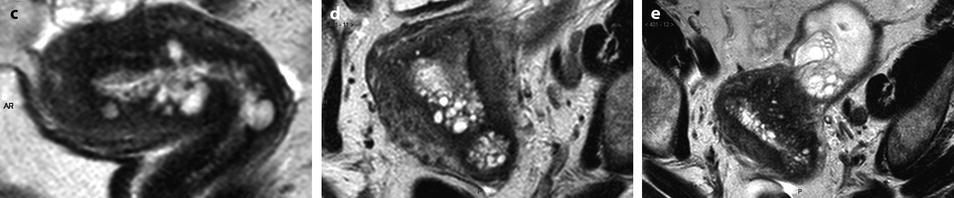

Fig. 22.10

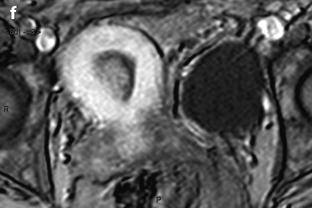

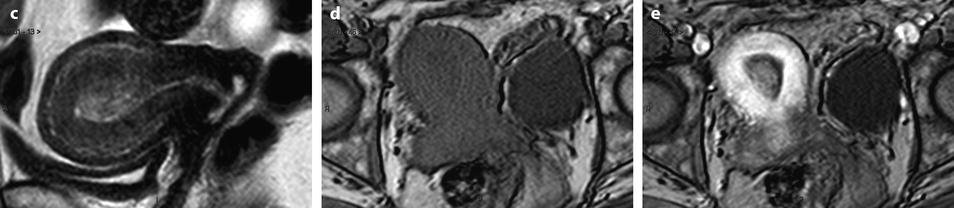

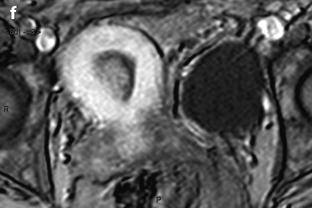

Endometrial polp with a vascular pedicle. Longitudinal (a) and transverse (b) EVS with color Doppler display an echogenic mass (with an echogenicity superior to myometrium), occupying most of the endometrial cavity. A peripheral hyperechoic line indicating a focal process allows to differentiate this mass from endometrial hyperplasia. This mass contains small cystic cavities underlined at their periphery by hyperechoic lines, which are typical for a benign process. Transverse view with color Doppler in (b) shows a vascular pedicle which definitely confirms the diagnosis of endometrial polyp. On MR sagittal T2 (c), the polyp has an overall intermediate signal, with some cystic spaces not as well demonstrated as on ultrasound. The limits of the mass are regular and the interface between the endometrium and the myometrium is well defined. On axial T1 (d) signal intensity of the polyp is slightly lower than myometrium. On DMR at the venous phase (e) cystic cavities are surrounded by a contrast uptake more intense than in the rest of the polyp. Thirty seconds later (f), the endometrial mass is clear defined with a contrast uptake inferior to myometrium and superior to normal endometrium

However, no arterial flow was detected in 30 % of nonfunctional polyps, 0 % of proliferative polyps, 11 % of secretory polyps, 25 % of hyperplastic polyps, and 33 % of malignant polyps in a series [8]; mean resistive index and mean pulsatility index were not different in the different categories.

3D reformation has the main interest to give a more precise location of the endometrial polyp than 2D (Fig. 22.11).

Fig. 22.11

Endometrial polyp in a 44-year-old asymptomatic woman. (a, b) Sagittal (a) and transverse (b) endovaginal ultrasound during the second part of the menstrual cycle discloses a 9 mm endometrial polyp (cursors in b), arising in the anterior endometrium at the level of the fundus, pushing the echogenic endometrial line posteriorly. The polyp is slightly more hyperechoic than the normal endometrium. (c) 3D reconstruction clearly shows the precise location of the polyp (arrow) in the right cornual endometrium that was not as clearly localized on the 2D views

22.2.2.2 Differential Diagnosis

Localized Lesions

1.

Submucous leiomyoma

Acoustic shadowing

Peripheral vascularization

2.

Clots

3.

Polypoid adenocarcinoma

4.

Polypoid adenofibroma and adenosarcoma

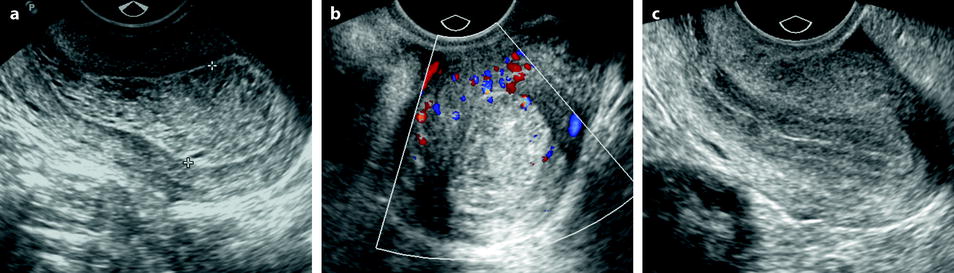

22.2.2.3 MR

Detection

Small polyps detected on EVS can be difficult to visualize or even can be overlooked on MR. It is the combination of a low intensity on T2W images and a higher uptake than endometrium on early DMR that best allows to detect them.

Morphologic Findings [10]

Small polyps (<1 cm), because of their signal intensity identical to the signal intensity of normal endometrium on T1 and identical or slightly less intense than endometrium on T2 are very difficult to detect, while they are much better displayed on endovaginal ultrasound (where they look more echogenic than normal endometrium). They can be only or better detected on DMR (Fig. 22.12). However, they can be also overlooked on DMR.

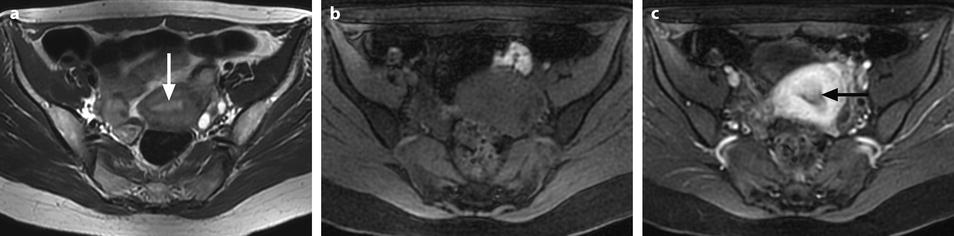

Fig. 22.12

Endometrial polyp hardly seen on T2 images and well depicted on DMR. (a) On T2, a small hypointense zone (arrow) is seen in the endometrium that could correspond to blood or partial volume effect. (b–f) On DMR before (b), at the arterial (c), venous (d), parenchymal (e), and late (f) phases, a well-delineated structure is seen at the early phases (arrow in c) contrasting with the less-enhancing normal endometrium. At the late phase, the polyp becomes isointense and indistinguishable from the normal endometrium

Larger polyps (>1 cm) are usually displayed. While on T1 they have roughly the same signal intensity as endometrium, on T2 they appear clearly as a well delineated endometrial masses, with a regular interface with the junctional zone, usually localized, containing sometimes a central fibrous core of lower signal intensity than endometrium and cystic cavities with regular borders of high signal intensity (Figs. 22.10 and 22.13).

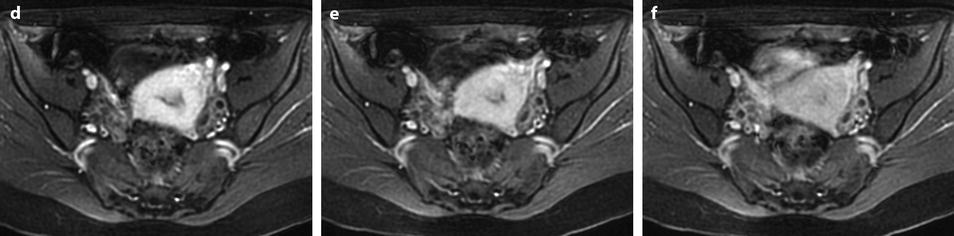

Fig. 22.13

Typical endometrial polyp containing small cystic cavities. A 65-year-old woman with hormonal treatment; absence of metrorrhagia. (a) Transvaginal ultrasound displays a typical endometrial polyp, hyperechoic with small glandulocystic cavities, surrounded by a hyperechoic line and associated to a clear vascular pedicle on color Doppler. (b, c) Sagittal (b) and axial (c) T2W images display the polyp as a hypointense intracavitary mass containing small cystic cavities and surrounded by a hyperintense endometrium. (d–g). DMR before (d) and after gadolinium injection (e–g) shows the polyp to enhance more rapidly than the normal endometrium with maximum contrast between the two structures at the early phase (e); however, the polyp is better delimited on the last phase (g)

Fig. 22.14

Endometrial polyp with glandulocystic cavities. A 61-year-old woman with right ovarian cyst, without hormonal treatment, absence of menometrorrhagia. (a) Transvaginal ultrasound, transverse view, discloses a 2.5 cm endometrial polyp (cursors) with small glandulocystic cavities. Otherwise the endometrium is thin with a small quantity of intracavitary fluid. (b) On axial T1W-FS MR after injection, the polyp appears as a well-delineated endocavitary mass containing small cystic cavities. Right cystadenoma is also displayed

22.2.2.4 Vascular Findings (Fig. 22.15)

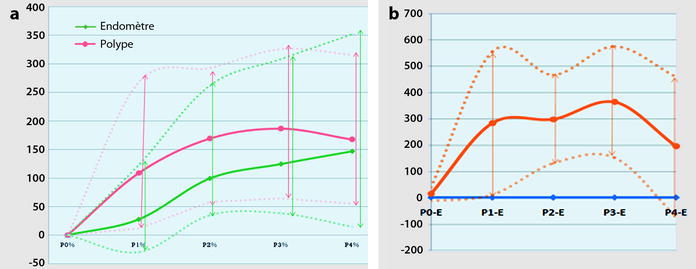

Fig. 22.15

Difference of contrast enhancement between polyp and endometrium. DMR, with sequences performed before and 25, 70, 125, and 240 s after injection (Materials: ten patients, Author’s personal series). (a) Right from the arterial phase, contrast in the polyp is superior to the endometrium. Peak enhancement in the polyp is at 2 min. The overall contrast enhancement in the polyp is superior to normal endometrium. (b) The plain orange line illustrates the mean difference of contrast enhancement between the polyp and the endometrium with the most marked difference at 70 and 125 s. Dots orange lines correspond to minimal and maximal difference in contrast uptake

1.

Right from the arterial phase, a significant contrast uptake is seen superior to the endometrium.

3.

The overall contrast uptake is superior to normal endometrium.

4.

In some cases, the center of the polyp (around the vascular pedicle) enhances earlier than the periphery (Fig. 22.13). This allows to differentiate a polyp from an endocavitary leiomyoma where contrast uptake is more prominent at the periphery at the early phase.

These morphologic and vascular findings are illustrated in the following figures (Figs. 22.10, 22.12, and 22.16).

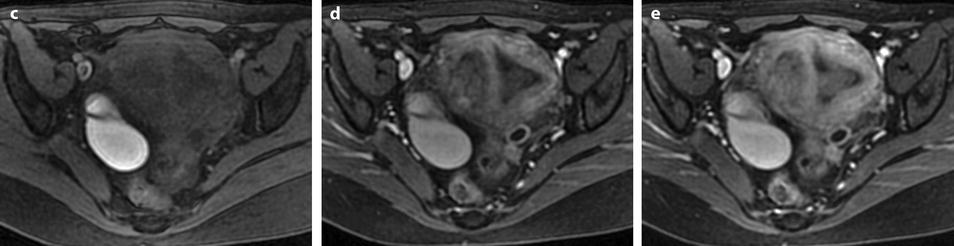

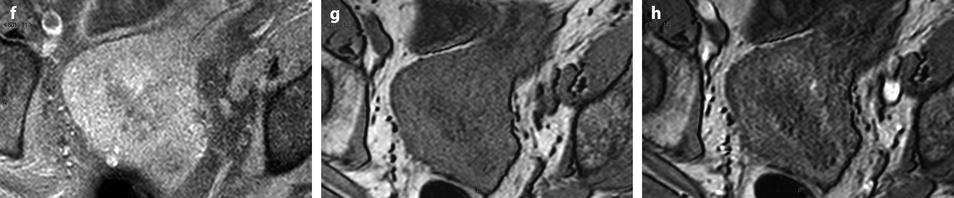

Fig. 22.16

Endometrial polyp well delineated on T2, DMR, and late post-contrast sequences. (a, b) Sagittal (a) and Axial (b) T2W images show in the posterior middle part of the endometrium an ovoid shape mass (arrows) with an intermediate signal intensity less than endometrium. Uterine leiomyomas and right endometrioma are also present. (c–g) On DMR before (c), at the arterial phase (d), the venous phase (e) and on the following phase (f), a significant contrast uptake in the mass superior to that of the endometrium is typical for endometrial polyp (arrow in f). On the delayed phase (g), signal intensity of the polyp is identical to endometrium. (h) Sagittal delayed T1FS sequence shows that the polyp, which has now the same intensity as the myometrium and the normal endometrium, is still visible because surrounded by some liquid

As it has been reported by Park et al. [11], if these findings are close to those of endometrial hyperplasia, they are different from those of endometrial carcinomas (Table 22.3).

Table 22.3

Vascular findings

DMR | Late contrast enhancement/outer M | Enhancement pattern | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Peak enhancement (time) | PE/WA (degree) | |||||

≤1 min | 2 min | 3 min | ||||

Polyp (9) | 0 | 4 | 5 | Intense PE | Homogeneous (6/9) | |

Hyperplasia (3) | 0 | 2 | 1 | Homogeneous (2/3) | ||

End Carc (32) | 23 | 9 | 0 | Mild gradual WA | Gradual WA<M | Homogeneous (29/32) |

Endometrial carcinoma shows usually earlier (1 min) mild peak enhancement and late gradual washout.

Sarcomas demonstrate early (1 min) more intense enhancement and late peak enhancement.

22.2.2.5 CT

Polyps are usually not visualized or visualized with difficult on CT. They can appear as a thickening of the endometrium. Hydrometry may help to detect them.

22.2.3 Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma (APA)

22.2.3.1 Pathology

It is a benign condition [4] although APA associated with adenocarcinomas have been rarely reported [12].

Histology

It is composed of

Irregularly shaped hyperplastic glands arranged haphazardly

Stroma containing abundant smooth muscle [13]. In fact, the stroma usually contains also a mixture of fibrous tissue and endometrial stroma which has suggested some authors [14] to designate this entity atypical polypoid adenomyofibroma to emphasize their stromal heterogeneity.

Extensive morular squamous metaplasia sometimes showing central necrosis may exaggerate the appearance of glandular crowding and raises concern regarding the possibility of a carcinoma.

Macroscopy [4]

It resembles a typical endometrial polyp.

It often involves the lower uterine segment.

22.2.3.2 Clinical Findings

During the reproductive and perimenopause period

Abnormal uterine bleeding

22.2.3.3 Follow-Up

Longacre et al. [14] reported that 45 % of the lesions treated conservatively recurred clinically, although none progressed to invasive carcinoma.

22.2.3.4 Radiologic Findings

MR Findings

The polypoid mass was [15]

On T1, isointense to myometrium

On T2, slightly hyperintense to myometrium containing markedly hyperintense foci

After contrast irregular enhancement

PET/MR fused images 18 F-FDG localized the abnormality to the endometrial cavity and showed focal intense accumulation with a SUV of 5.8.

22.3 Endometrial Hyperplasia

22.3.1 Generalities

22.3.1.1 Definition

Proliferation of glands of irregular size and shape with an increase in the gland/stroma ratio compared with proliferative endometrium. Generally diffuse but may be focal.

22.3.1.2 Pathology [16]

Macroscopy

Endometrium has a velvety knobby surface with spongy tissue and vague borders.

Diffuse thickening is usually present, but focal overgrowth may occur and simulate a polyp.

Histology

The lesions are classified in:

1.

Typical or atypical hyperplasia: according to the cytologic findings

Typical hyperplasia: absence of cytologic atypia

Atypical hyperplasia: presence of cytologic atypia: (a) stratified cells (b) loss of polarity (c) increase in the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio

2.

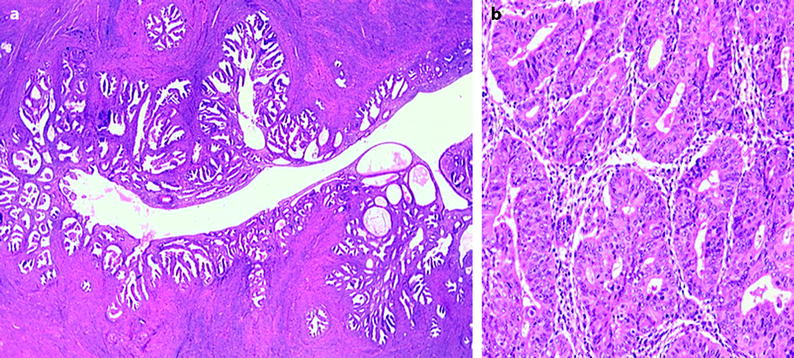

Simple or complex hyperplasia according to the architectural features (Fig. 22.17):

Fig. 22.17

(a) Simple hyperplasia. (b) Complex hyperplasia

Simple hyperplasia: the glands are cystically dilated with occasional outpouchings surrounded by an abundant cellular stroma. Occasionally the glands are minimally dilated.

Complex hyperplasia: crowded glands with little intervening stroma.

Fewer than 2 % of hyperplasias without cytologic atypia progress to carcinomas whereas 23 % of atypical hyperplasias progress to carcinomas [16].

22.3.1.3 Clinical Features

Hyperplasia develops as a result of exogenous unopposed estrogenic stimulation or a history of persistent anovulation. It is most common in perimenopausal and menopausal women and uncommon during the reproductive years. Bleeding may be moderate, heavy, or absent (hyperplasia being fortuitously discovered during biopsy).

It can be associated to some special clinical conditions:

Obesity associated with PCOD

Estrogen secreting ovarian tumors (see Chap. 11)

22.3.2 Imaging Findings

22.3.2.1 Ultrasound

Ultrasound findings are reported in Table 22.4 (Figs. 22.18 and 22.19).

Table 22.4

Ultrasound findings of endometrial hyperplasia

1. Morphological findings |

Thickness (diffuse or more rarely focal thickening of the endometrium) |

Postmenopausal woman |

–Without hormonal treatment >5 mm |

–With hormonal treatment >8 mm |

Reproductive age years |

–No clear cutoff (depending on the time of study during the menstrual cycle) |

Pattern |

–Regular interface with myometrium |

–Echogenicity as normal endometrium |

–Homogeneous (non-suggestive) or contain cystic spaces (very suggestive) |

2. Doppler findings: |

Regular vessels when seen |

3. Hysterosonography [9] |

Better evaluates the thickness and detects or rules out associated polyps |

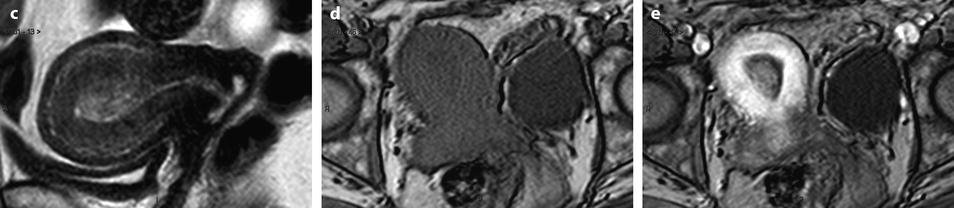

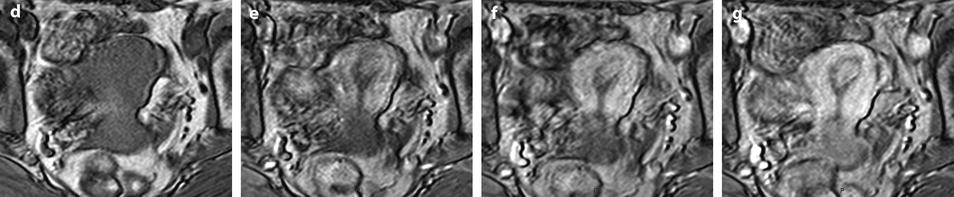

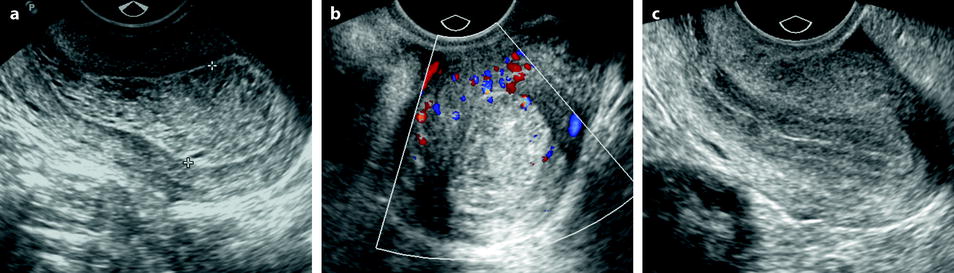

Fig. 22.18

Endometrial hyperplasia. A 39-year-old woman with PCOS and secondary amenorrhea. (a) Transvaginal sagittal ultrasound discloses a retroverted uterus with a diffuse echogenic and homogeneous thickened endometrium (18 mm for two layers) from the fundus to the isthmus. This pattern is suggestive of endometrial hyperplasia. The peripheral basal endometrial line is well seen. (b) Transverse view with color Doppler does not show a vascular pedicle. (c) Ultrasound performed after treatment with Duphaston shows a normal 7 mm endometrium (for two layers) with a well-delineated endocavitary line

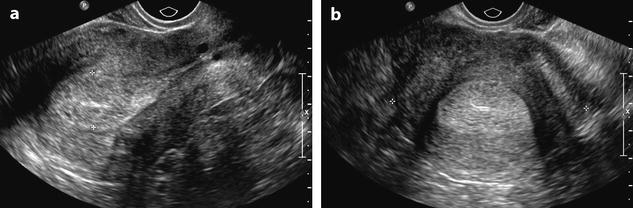

Fig. 22.19

Endometrial hyperplasia in a 45 years old woman with menometrorrhagia. (a, b) Sagittal (a) and transverse (b) transvaginal ultrasound display a thickened endometrium (20 mm for two layers) containing small cystic cavities. The endocavitary line is well displayed on both views, well centered. The peripheral basal endometrium appears as a peripheral hyperechoic line. (c, d) Hysterosonography confirms absence of focal endometrial growth and a thickened regular hyperechoic endometrium. Echoic lines in the endocavitary liquid correspond to blood and/or air

In a series of 23 patients with hyperplasia of the endometrium, metaplasia, or both studied by transvaginal sonography and saline hysterosonography, Jorizzo et al. [9] found endometrial thickness to increase with atypia, complexity of hyperplasia and associated metaplasia, but with a lot of overlap. Lobular contours were present in 9 % patients. Cysts were contained in the thickened endometrium in 57 % of patients. Concomitant polyps were present in 26 %.

22.3.2.2 MR

Simple and Typical Hyperplasia

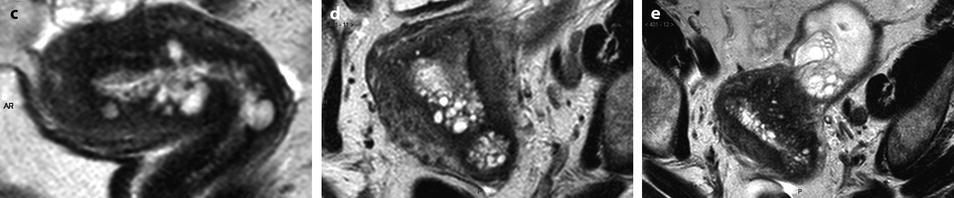

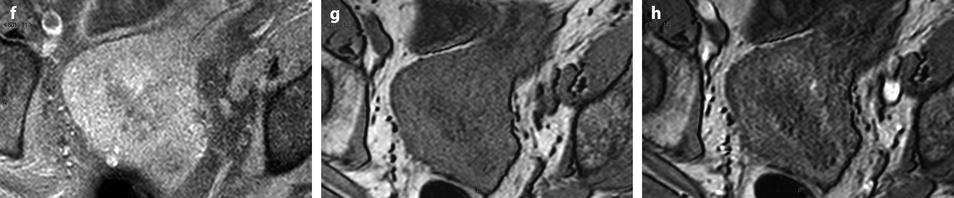

Simple and atypical hyperplasia presents as a diffuse or less commonly localized endometrial thickening sometimes containing cystic spaces (Fig. 22.20). The interface with the myometrium is well defined.

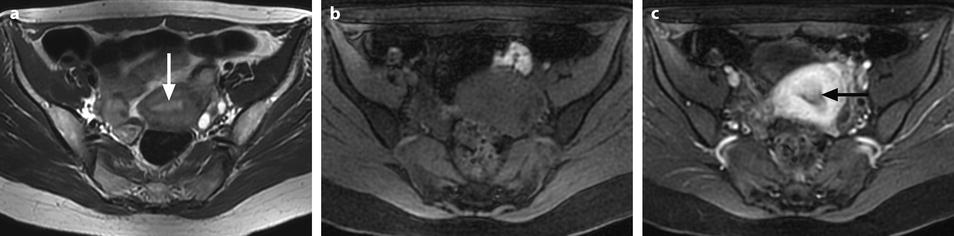

Fig. 22.20

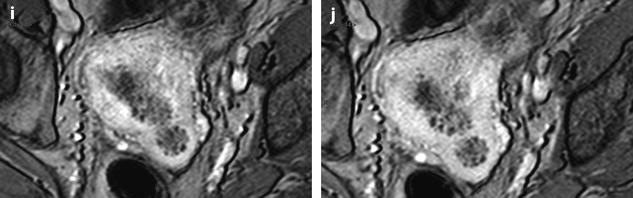

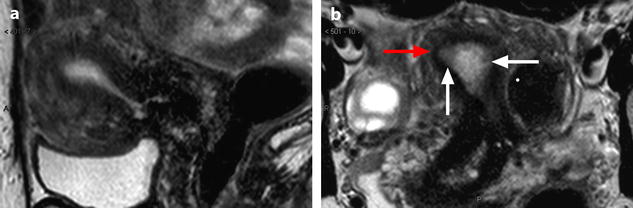

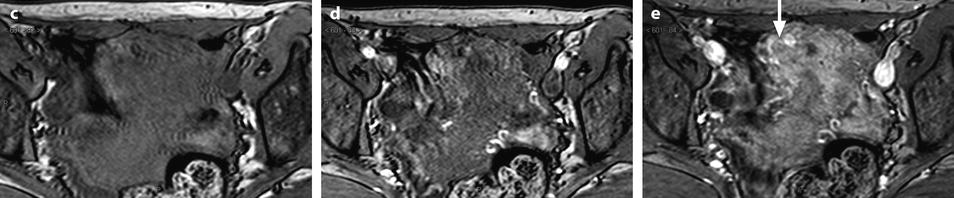

Endometrial hyperplasia with foci of mucinous metaplasia and associated adenomyosis. Association with a mucinous ovarian borderline cystadenoma. Seventy-five-year-old woman with metrorrhagias and hydrorrhea. (a, b) Longitudinal EVS (a) and (b) display some fluid in the endometrial cavity, a thickening of the endometrium at 7 mm, containing small cystic cavities. Cystic spaces are also visualized in the inner myometrium related to adenomyosis. (c–e) MR T2W sagittal (c) axial (d, e) depict a thickening of the endometrium containing unusual numerous small cystic cavities suggesting endometrial hyperplasia. Large and small endometrial cysts in the myometrium are related to adenomyosis. On (e), a left tubo-ovarian mass is seen that was related to a mucinous borderline tumor with tubal intussusception at pathology. (f) On axial T1 fat suppression, no hemorrhage is displayed in the endometrium. (g–j) On DMR without injection (g), at the arterial phase (h), few vessels are visualized in the endometrium, with unusual tortuous vessels at the endometrial myometrial junction. At the venous phase (i) and on the delayed (j), a slight contrast uptake is depicted. Prospective diagnosis: endometrial hyperplasia with adenomyosis. Microscopy: confirmed the diagnosis and showed association to mucinous metaplasia of the endometrium

1.

The thickened endometrium

On T2, hyperplasia is isointense or slightly hypointense relative to the normal endometrium.

On DMR, during the early post-contrast images, hyperplasia like the normal endometrium is hypointense relative to the myometrium.

On the delayed, it becomes isointense or hyperintense or sometimes slightly hypointense relative to the adjacent myometrium.

2.

Small hyperintense foci on T2, hypointense after injection representing cystic glandular dilatations may be seen [17].

Atypical and Complex Hyperplasia

Although Jorrizo et al. [9] have reported that the thickness of endometrium in atypical and complex hyperplasia is significantly higher than in simple and typical hyperplasia, the pattern of this last entity has not been reported. In our case (Fig. 22.21), the endometrium does not contain any cystic spaces; the overall signal of endometrium is not as hyperintense as in simple and typical hyperplasia, limitation with the junctional zone is not as clearly demarcated. However, at present, the final diagnosis is histological.

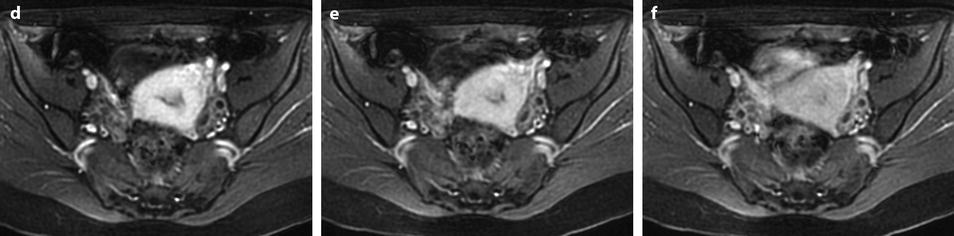

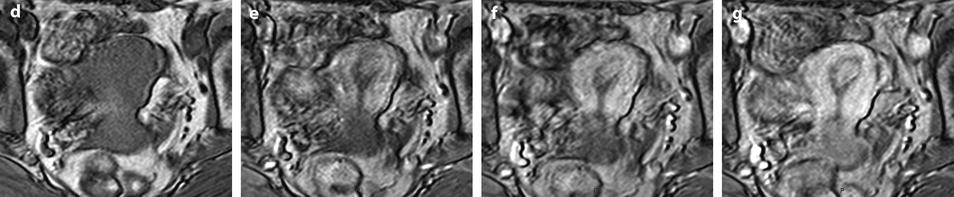

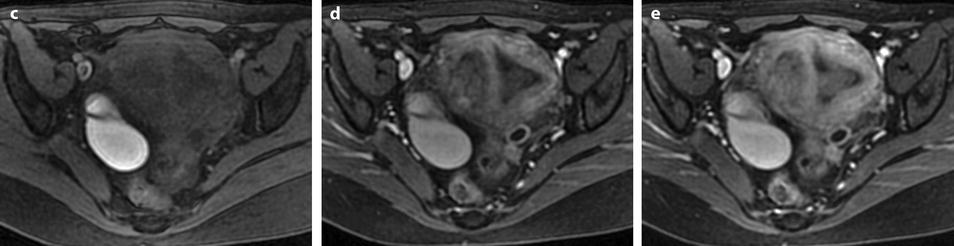

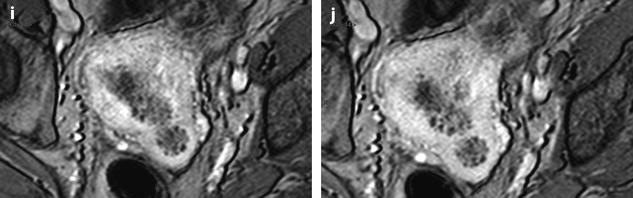

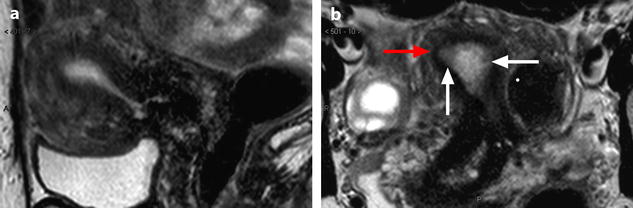

Fig. 22.21

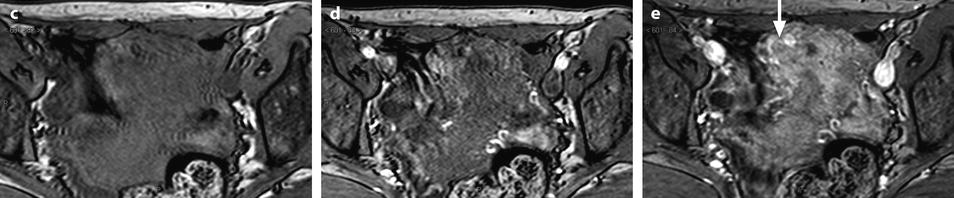

Atypical and complex hyperplasia. Fifty-year-old woman. Absence of clinical finding. During a routine EVS examination, an endometrial polyp is discovered. At pathologic examination, atypical and complex endometrial hyperplasia is diagnosed. MR sagittal (a) and axial T2 (b) displays a diffuse thickening of the endometrium of 13 mm (measured in the upper third). No cystic space is visualized in the endometrium, signal intensity of the endometrium is not as hyperintense as usually, and signal intensity is not homogeneous, with some areas of intermediate signal (white arrows). In the right and upper portion of the endometrium, the limit between the outer part of the endometrium and the junctional zone is not clearly demarcated, and the junctional zone at this point is thinner (red arrow). On DMR without injection (c) and at the arterial phase (d), a slight increase of arterial vascularization is displayed at the same level, with at the venous phase (e), a slightly increase of the venous vascularization (arrow)

22.3.2.3 CT

As for polyps, hyperplasia in not well characterized on CT. It could appear as thickening of the endometrium. Cystic spaces are hard to see.

22.3.3 Endometrial Cellular Changes: Metaplasia, Cellular Differentiation [16]

22.3.3.1 Definition

Metaplasia is the replacement of one type of adult tissue by another type that is not normally found in that location.

In contrast to hyperplasia that is a proliferative response to estrogenic stimulation, metaplasia is a cytoplasmic differentiation secondary most commonly to estrogenic and progestational stimulation.

22.3.3.2 Histology

Eosinophilic changes are the most common, among them several types of eosinophilic cytoplasmic transformation: ciliated cells, squamous cells, oncocytes, and papillary and surface syncytial changes.

Other types are:

Squamous cells, round or polygonal, may be spindle shaped forming a circumscribed nest (squamous morule)

Ciliated cells (tubal metaplasia)

Secretory cells: columnar cells with sub- or supranuclear vacuoles

Clear cells: polygonal cells with clear cytoplasm containing glycogen

Hobnail changes, reminiscent of the Arias-Stella reaction

Mucinous

The various forms of cellular differentiation are typically focal when unaccompanied by hyperplasia but can be diffuse when hyperplasia is present.

22.3.3.3 Clinical Features

Metaplasias develop most commonly in response to estrogenic and progestational stimulation.

The frequent association of the various cytoplasmic changes with hyperplasia is probably because both result from a hyperestrogenic state.

More than 70 % of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with metaplasia have received exogen estrogen [18]. Most young women with metaplasia have clinical manifestations of anovulation and primary infertility.

Metaplasia also may occur in benign conditions as polyps, endometritis, trauma, and vitamin A deficiency.

22.4 Primitive Malignant Tumors

22.4.1 Endometrial Carcinoma

22.4.1.1 Endometrial Intraepithelial Carcinoma (EIC) [16]

Definition

Markedly atypical nuclei identical to those of invasive serous carcinomas, lining the surfaces and glands of an atrophic endometrium.

Serous carcinoma is the prototypic endometrial carcinoma that is not related to estrogenic stimulation and typically occurs in the setting of endometrial atrophy.

Macroscopy

The surface often demonstrates a slightly papillary contour.

EIC can be found on the surface of a polyp in an atrophic endometrium.

22.4.1.2 Endometrial Invasive Carcinoma

Different Pathologic Types

Endometrioid Carcinoma

The most common form accounting for more than three quarters of cases.

Definition

(a)

This tumor is so-called because it resembles proliferative phase of the endometrium.

(b)

It does not contain more than 10 % of squamous, serous, mucinous, or clear cell differentiation (if these components are more than 10 %, it is called mixed type carcinomas).

Pathology

Gross findings are reported in Table 22.5 [16] (Fig. 22.22).

Table 22.5

Macroscopic findings of endometrioid carcinoma

1. Morphologic findings |

–Focal or diffuse |

–Endometrial surface shaggy, glistening and tan, and may be focally hemorrhagic |

–Almost uniformly exophytic even when deeply invasive |

–At times separated polypoid masses |

–Necrosis usually not evident macroscopically in well-differentiated carcinoma may be seen in poorly differentiated carcinoma |

2. Extension |

(a) Myometrial invasion |

–Well-demarcated gray white tissue with linear extensions beneath an exophytic mass |

–Multiple white nodules with yellow areas of necrosis within the uterine wall |

(b) In the lower uterine segment: common |

(c) In the cervix in 20 % of cases |

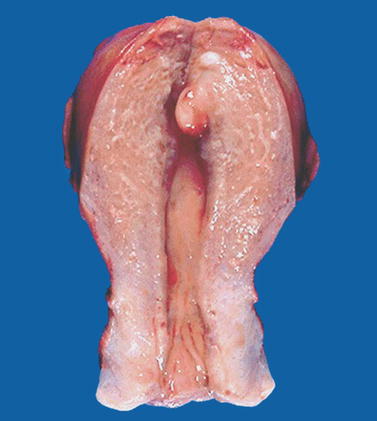

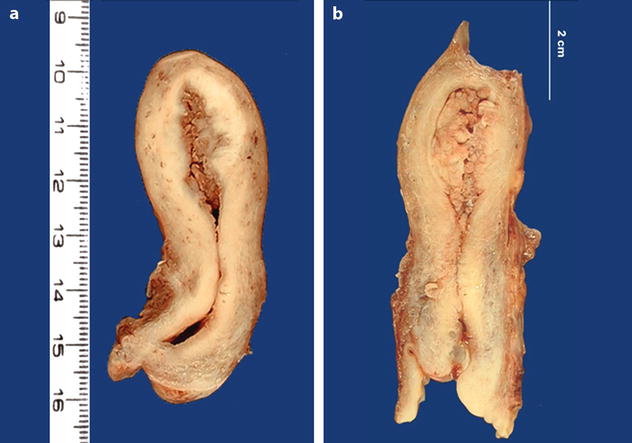

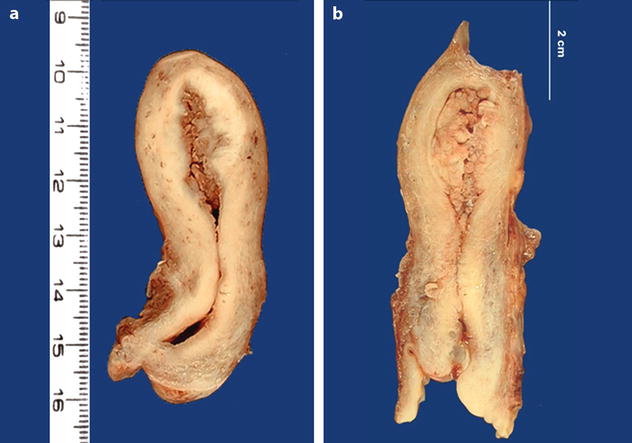

Fig. 22.22

Endometrial carcinoma: macroscopic specimen. (a, b) Exophytic mass occupying the entire endometrial uterine cavity extending to the posterior wall into the inner half of the myometrium. The isthmus and the cervix are not invaded

Microscopic Findings

Grading [16]

Grade is based on cytologic and architectural features:

1.

Cytologic features (Nuclear features)

Grade 1. Nuclei oval, mildly enlarged, evenly dispersed chromatin.

Grade 2. Features intermediate between 1 and 2.

Grade 3. Nuclei markedly enlarged and pleomorphic, irregular coarse chromatin, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli.